Abstract

The shadow economy’s size and impact remain subjects of extensive research and debate, holding significant implications for economic policy and social welfare. In Lebanon, the ongoing crisis since 2019 has exacerbated severe economic challenges, with the national currency’s collapse, bank crisis, and foreign reserve deficits. The World Bank reports Lebanon’s financial deficit surpassed $72 billion, three times the GDP in 2021. Despite a drastic decline in GDP, imports have surged to near-pre-crisis levels, exacerbating economic woes and indicating a constant outflow of foreign currencies. Considering such contracting facts, this paper aims to investigate global factors influencing the shadow economy and discern their manifestations in Lebanon during financial crises. Our methodology involves a comprehensive literature review, alongside a case study approach specific to Lebanon. This dual-method strategy ensures a detailed understanding of the shadow economy’s impact and the development of actionable insights for policy and economic reform. Through this approach, we seek to contribute to a nuanced understanding of Lebanon’s economic landscape and provide valuable guidance for policy decisions aimed at reducing corruption, promoting transparency, and fostering a robust formal economy. The increase in the shadow economy raises the formal economy risk, as resources and activities diverted to informal channels hinder the growth and stability of the official economic sector. Although focusing on Lebanon, this analysis deepens the comprehension of the economic landscape and provides valuable guidance for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders, aiming to address the root causes of informal economic activities and promote sustainable growth in developing countries in general.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context

The shadow economy—comprising unregulated economic activities that evade taxes and legal frameworks—presents a significant economic development risk due to its profound implications for economic stability and social welfare. The persistence of the shadow economy undermines formal economic structures, hampers effective policy implementation, and exacerbates socio-economic disparities. Understanding the dynamics of the shadow economy is crucial, especially during periods of financial crisis, as it can reveal how unregulated activities contribute to broader economic development risks.

Recent literature underscores the multifaceted nature of the shadow economy. Canh et al. (2021) highlight the influence of economic integration and institutional quality on shadow economic activities, while Chletsos and Sintos (2024) examine how International Monetary Fund (IMF) interventions can shape informal sectors. Dreher and Schneider (2010) explore the interplay between corruption and the shadow economy, revealing its extensive socio-economic consequences. Additionally, the shadow economy might also raise environmental risks, as shown by Cozma et al. (2021), who highlight its significant impact on illegal logging. The study reveals how corruption and economic crimes, core elements of the shadow economy, exacerbate deforestation rates. By analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data, the research underscores the role of governance quality, press freedom, and wood export share in driving deforestation, thereby informing policies to combat illegal logging and protect the environment. This illustrates the extensive socio-economic and environmental consequences of the shadow economy. These studies illustrate how various factors, including governance quality and economic policies, contribute to the shadow economy’s expansion, risks, and persistence.

Lebanon’s late and ongoing economic crisis, which began in 2019, provides a pertinent context for studying the shadow economy. The collapse of the national currency, escalating trade deficits, and severe economic contraction (World Bank Group 2021b) have exacerbated the challenges facing Lebanon’s formal economy.

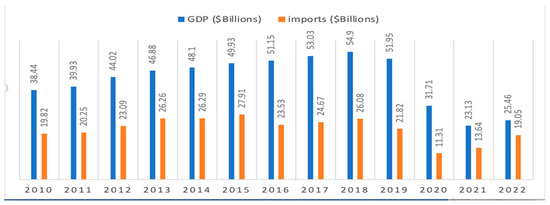

According to one of the World Bank reports (World Bank Group 2021b), Lebanon’s financial deficit exceeded $72 billion in 2021, which was three times the country’s GDP. Furthermore, considering the downward trajectory of GDP from about $52 billion in 2019 to less than half in 2022 ($25.46 billion), the surge in imports exacerbates Lebanon’s economic woes, underscoring the magnitude of the challenge at hand. Imports have remarkably rebounded to their pre-crisis levels, while the trade deficit continues to expand due to a decline in exports. In 2022, as per data from Banque Du Liban (BDL, the Central Bank of Lebanon), imports reached a staggering $19.05 billion, representing a significant increase of $5.41 billion compared to the previous year, marking a rise of 39.68% from 2021 ($13.64 billion) and a striking 68.47% surge from 2020 ($11.31 billion) (Banque du Liban (BDL) 2023b; Gemayel 2023). These import levels are almost equivalent to the figures recorded in the five years prior to the crisis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

GDP and import fluctuations in Lebanon from 2010 to 2022 (authors’ compilation of data from Banque du Liban (BDL) 2023b; World Bank 2023b).

The surge in imports amid Lebanon’s economic crisis, coupled with the persistent downturn in GDP, signals a concerning trend: the formal economy is struggling to return to pre-crisis levels. Despite economic hardships, imports have rebounded to near-pre-crisis levels, indicating a reliance on external goods and services and thus a constant outflow of foreign currencies. With the recurrence of financial crises and their adverse effects, it becomes crucial to shed light on the informal economy, commonly known as the shadow economy. This sector represents a significant portion of a country’s GDP, especially in developing nations. This suggests that the formal economy is not recovering as expected, potentially fueling informal economic activities and the expansion of the shadow economy.

The escalation of the shadow economy heightens the risk to the formal economy, diverting resources and activities into informal channels that impede the growth and stability of the official economic sector. Sustainability risks emerge across economic stability, environmental impact, social consequences, governance challenges, and long-term development goals. Addressing these risks requires robust policies to promote transparency, strengthen regulatory frameworks, and foster the formalization of informal activities, ensuring sustainable economic, environmental, and social outcomes.

In addition to internal concerns within companies, such as operational efficiency, internal controls, and corporate indebtedness, adopting strategic and personalized approaches to financing and risk management (Tavares et al. 2024), as well as financial education (Santos and Tavares 2020), remains essential for mitigating external risks. The shadow economy, in particular, can significantly impact risk management practices and overall performance by introducing uncertainties and unregulated activities that disrupt formal economic operations and planning.

In this paper, we utilize a dual-method approach: a comprehensive literature review and a case study specific to Lebanon. The literature review includes peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and reputable reports, ensuring a thorough understanding of the shadow economy’s global and local dynamics. The case study provides contextual insights into Lebanon’s economic conditions, allowing us to apply theoretical findings to the local context. This methodology enables a detailed examination of the shadow economy’s impact and its implications for Lebanon’s economic development.

Thus, the aim of this paper is to investigate the global factors influencing the shadow economy and to discern their specific manifestations within Lebanon, particularly during times of the financial crisis since 2019. By combining a broad literature review with a focused case study, we aim to provide a nuanced analysis that informs policy and economic reform efforts in Lebanon.

1.2. Research Aim, Questions and Value

Arising from the above, this study investigates two critical questions:

- What are the key global factors influencing the shadow economy?

- How do these factors and indicators manifest in the context of Lebanon during times of its financial crisis?

The research questions aim to elucidate two key aspects of the shadow economy’s dynamics. The first question seeks to identify the general factors influencing the shadow economy, providing a broader understanding of international drivers that affect informal economic activities. The second question focuses on how these global factors specifically manifest within Lebanon during its financial crisis, aiming to apply these international insights to the local context.

The methodology is based on secondary data analysis and a comprehensive theoretical review at both the local and international levels. By concentrating on the variables identified in the literature, we analyze their applicability and relevance to the Lebanese context, thereby assessing the indicators and situation in Lebanon. Moreover, we address the gap in the existing literature by adopting a theoretical framework grounded in institutional economics to analyze the dynamics of the shadow economy in Lebanon. Unlike previous studies that predominantly rely on quantitative methods, our qualitative approach allows for a deeper exploration of contextual factors and socio-economic dynamics unique to Lebanon.

The significance of our research lies in its potential to contribute to the existing body of knowledge surrounding the factors impacting the shadow economy in general and in Lebanon in particular, with a focus on the effects on government revenues and social welfare. By unraveling the complexities of the shadow economy, we aim to provide actionable insights that can inform policy decisions for reducing corruption, promoting transparency, and fostering a robust formal economy. Through our analysis, we strive to deepen the understanding of Lebanon’s economic landscape and offer valuable guidance for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders. Ultimately, our work endeavors to address the root causes of informal economic activities and promote sustainable economic development in Lebanon.

The paper begins with a literature review, exploring the informal economy and its ties to corruption and formal economic systems. It adopts an institutional economics framework to analyze secondary data on Lebanon’s shadow economy. Then, it discusses key indicators of Lebanon’s informal economy: unemployment, taxation, government regulations, financial crises, smuggling, and cash circulation. Policy recommendations follow. Finally, the paper emphasizes the need for structural reforms to address fiscal instability and promote economic and social welfare in Lebanon.

2. Literature Review

2.1. An Overview of the Informal Economy

The informal or shadow economy encompasses activities that occur outside the purview of “bureaucratic public and private” systems (Blanton and Peksen 2021). These activities involve elements such as smuggling, bribery to access desired services or products, and informal employment driven by market structures (Mishchuk et al. 2020).

Empirical studies, such as the work conducted by Schneider (2005), have been instrumental in estimating the size of the shadow economy in various countries, including those in the developing, transitioning, and highly developed OECD economies between 1990 and 2000. Schneider’s study revealed that the shadow economy accounted for 41% of the official GDP in developing countries, 38% in transition economies, and 17% in OECD countries. A key driver for the growth of the shadow economy is the burden imposed by taxation and social security contributions. It was observed that a 1% increase in the shadow economy in developing countries leads to a 0.6% decrease in the growth rate of the official GDP, while in developed and transitioning economies, the shadow economy increases by 0.8% and 1.0%, respectively. Furthermore, the size of the shadow economy varies significantly across countries and time periods, with developing and transitioning economies typically exhibiting larger shadow economies than highly developed OECD nations (Schneider 2005).

As indicated by newer estimates from Medina and Schneider (2018), in Europe, the shadow economy is thought to account for approximately 20% of the GDP. However, in Eastern Europe and post-Soviet regions, the figures are even higher, ranging from 25% to 45% (Medina and Schneider 2018). Recent studies further expand on these findings:

Medina and Schneider’s 2018 study utilized a light intensity method as an alternative indicator within the Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) framework. This study provided estimates of the shadow economy for 158 countries from 1991 to 2015, addressing earlier criticisms by implementing the Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) method to enhance accuracy and reliability. This study underscores the shadow economy’s complexity and the necessity for robust estimation methods (Medina and Schneider 2018).

Additionally, a 2023 report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reviewed shadow economies worldwide over the past 20 years, highlighting significant variations in their size across different regions and time periods. This report reinforced that developing and transitioning economies typically exhibit larger shadow economies than developed OECD nations. It also discussed the socio-economic impacts, such as the role of informal networks and social capital in perpetuating corruption and unethical behavior within shadow economies (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2023).

Furthermore, a study published in Emerald Insight explored the interrelationship between corruption and the shadow economy, using data from the World Development Indicators database and building upon Medina and Schneider’s 2018 estimates. The study found that shadow economies often rely on informal networks, which can facilitate corrupt practices due to a lack of accountability and transparency. This research further solidifies the understanding of how shadow economies and corruption are interlinked (Nguyen and Liu 2023).

While the shadow economy can be viewed as an engine of innovation, it also brings about significant social side effects, such as unprotected working conditions due to its unregulated and clandestine nature (Kraemer-Mbula and Wunsch-Vincent 2016). Other negative effects of the shadow economy include a high poverty rate, high share of income spent on basic expenditures (mainly food), lack of housing opportunities, and lack of social safety (Mishchuk et al. 2020). Furthermore, it has also been empirically proven the effects of the shadow economy on government revenues, unfair competition over pricing (between entities paying taxes and those functioning under an informal economy), and impacts on economic growth in developing countries (Tanzi 2002).

In the context of Lebanon, the informal economy plays a particularly significant role due to the country’s ongoing economic crisis and political instability. Recent estimates suggest that Lebanon’s informal sector is notably larger, exacerbated by the country’s severe economic challenges. The International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s (2023) report highlights that Lebanon’s shadow economy has expanded significantly as the formal economy struggles to recover, driven by regulatory deficiencies and economic collapse. Lebanon’s shadow economy is intertwined with corruption and inadequate governance, exacerbating economic instability and undermining social welfare (Nguyen and Liu 2023). The impact of the shadow economy in Lebanon includes exacerbated poverty rates, increased reliance on informal networks, and reduced government revenues. Addressing these issues is crucial for developing targeted policies to enhance transparency, improve governance, and formalize informal economic activities, thus promoting sustainable economic development in Lebanon.

The next section will focus on the interconnections between corruption, the formal economy, and the shadow economy. By integrating this discussion into the literature review, we aim to offer a comprehensive understanding of the global dynamics influencing the shadow economy and lay the groundwork for analyzing its specific manifestations in Lebanon. This exploration will highlight how global factors intersect with local conditions in Lebanon, where corruption and institutional weaknesses significantly shape the shadow economy. By examining these interconnections, we seek to uncover the mechanisms and dynamics pertinent to Lebanon’s economic context, thereby grounding our analysis in both global perspectives and local realities.

2.2. Interlinking Corruption, Formal Economy, and Shadow Economy

To investigate the complex relationship between corruption, the formal economy, and the shadow economy, it is important to establish clear conceptual boundaries. Corruption, defined as the misuse of public resources for personal gain, has been widely recognized as a major impediment to economic and social development (Rose-Ackerman 1999). The formal economy refers to registered economic activities that are governed by legal frameworks, regulations, and taxation systems. On the other hand, the shadow economy encompasses unregistered economic activities that operate outside the purview of official regulations and often involve noncompliance with tax obligations (Schneider and Enste 2000).

Previous research exploring the interaction between corruption and the shadow economy has focused on estimating the size and impact of the shadow economy and identifying the factors that contribute to its growth (Schneider and Buehn 2016; Sharipov 2015; Friedman 2014). Poor institutional quality and tax evasion have been identified as key drivers of the shadow economy (LaPorta et al. 1999; Tanzi 1999). Institutional economics emphasizes the role of institutional quality, including corruption, regulatory discretion, judicial systems, the rule of law, and bureaucracy, in shaping economic behavior (Phuc Canh 2018; Schneider and Enste 2000).

Corruption has a detrimental effect on institutional quality, leading to higher labor costs for official economic activities and incentivizing economic agents to engage in informal or concealed activities (Phuc Canh 2018; Schneider and Enste 2000). Inadequate constraints on government powers, regulatory burdens, and failing judicial systems create an environment where individuals may opt for informal economic activities and participate in the shadow economy (Torgler and Schneider 2009; Dreher et al. 2009; Berdiev et al. 2018).

Conversely, the shadow economy can also influence corruption and the formal economy. Some studies suggest that the shadow economy can act as a substitute for corruption, allowing economic agents to avoid official taxes and bureaucracy (Choi and Thum 2005; Ackerman 1997). Factors such as political stability, competent governance, and effective regulations have been found to be negatively correlated with the size of the shadow economy, while bureaucracy shows a positive association (Friedman 2014). However, it is important to note that the relationship between corruption, the formal economy, and the shadow economy is multifaceted and can work in different ways depending on the specific context and circumstances.

The presence of a significant shadow economy poses risks to economic development and societal well-being. It leads to fiscal losses due to tax evasion, contributes to income inequality, and distorts the accurate measurement of income distribution. The shift of economic activities from the formal to the informal sector exacerbates income polarization, while the impact of the shadow economy on secondary income generation undermines social safety nets, resulting in challenges such as poverty, inefficient cost structures, and limited housing opportunities (Mishchuk et al. 2020).

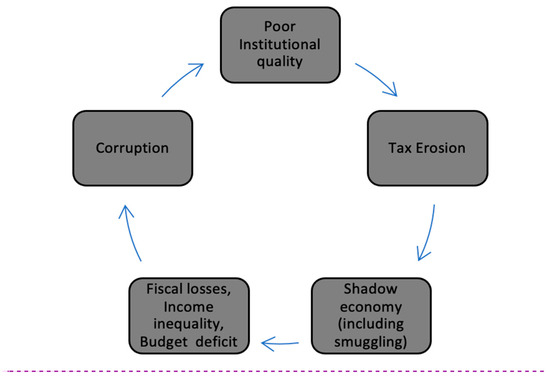

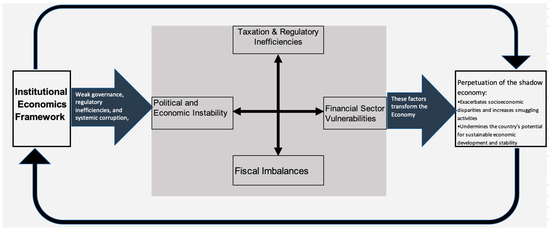

Given these conceptual boundaries and the complexities of the relationship between corruption, the formal economy, and the shadow economy, it is imperative to understand the underlying mechanisms, dynamics, and potential policy implications. By examining these interconnections, this study sheds light on the factors that influence the size and behavior of the shadow economy and how corruption and institutional quality play a role in shaping these dynamics. Figure 2 summarizes the main factors related to the shadow economy and the cycle it creates based on the above literature review.

Figure 2.

Summary of factors related to the shadow economy (source: author).

Schneider (2000) employed causal models incorporating latent variables to estimate the size of the shadow economy across different countries. These latent variables are not directly observable but have operational implications for the relationships among observable variables. The observable variables act as causes and serve as indicators of the hidden variables.

In his research, Kanniainen et al. (2004) built on that causal model. He utilized the Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) method and formulated six hypotheses. He postulated that the shadow economy would positively respond to the following factors:

- Tax rates (both direct and indirect) and social security contributions;

- State regulation indicated by the percentage of total employment allocated to public administration;

- Lower tax morality;

- Decrease or deterioration of state transfer and public goods quality;

- Higher unemployment and lower GDP per capita;

- The amount of cash transactions.

The econometric results of Kanniainen’s study suggest that taxation and social security variables significantly influence the expansion of underground economies. The research underscores the importance of controlling the tax burden to reduce the size of these economies and emphasizes the need for public education regarding the benefits of contributing to the formal economy. Additionally, economic factors such as unemployment and GDP per capita influence individuals’ willingness to participate in the official economy. Social benefit policies may have more significant employment benefits than previously believed, and state transfers may act as incentives to draw individuals out of the underground economy. Furthermore, the size of a shadow economy is influenced by a country’s economic performance, exhibiting significant variation across nations and over time.

Schneider and Buehn (2016) explored various methods for gauging the dimensions of the shadow economy and delved into their respective strengths and limitations. Their study serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it underscores the absence of an impeccable method for quantifying the size and evolution of the shadow economy. While delving into greater detail on the MIMIC method, which offers flexibility in obtaining macro-level estimates, the paper secondly concentrates on defining the shadow economy and its causative factors. It also provides a comparative analysis of the shadow economy’s size using diverse estimation techniques. Their findings reveal significant disparities in measurement methods, yielding divergent and sometimes inconsistent results. The survey method predominantly focuses on households, occasionally overlooking firms, leading to issues such as non-responses, erroneous data, and limited financial figures instead of value-added metrics. The discrepancy method grapples with challenges arising from rough estimates, unclear assumptions, and a lack of transparency in calculation procedures. The monetary and electricity methods tend to generate elevated estimates, but only offer macro-level data, posing complications in converting electricity consumption into value-added estimates. The widely used MIMIC method provides relative coefficients rather than absolute values, and it is highly sensitive to changes in data and specifications, making it difficult to discern causal factors and indicators. The overall conclusion is that there is no single flawless method, underlining the importance of employing multiple approaches to enhance our comprehension of the shadow economy’s size and evolution (Schneider and Buehn 2016).

Given the limitations inherent in estimating the size of the shadow economy and the complexities of the Lebanese market dynamics, this paper opts for a theoretical framework rather than quantitative analysis. While quantitative methods have traditionally been employed to measure the shadow economy, the intricacies of accurately quantifying informal economic activities in Lebanon pose significant challenges. Factors such as data availability, reliability, several exchange rates, and the dynamic nature of informal transactions contribute to the difficulty in conducting precise quantitative assessments. Therefore, a theoretical approach allows us to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms and interdependencies between corruption, the formal economy, and the shadow economy. By examining existing literature and theoretical frameworks, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the shadow economy in Lebanon and their implications for economic policy and social welfare. This theoretical lens enables us to explore the conceptual boundaries of corruption, institutional quality, and economic behavior, laying the groundwork for insightful analyses and policy recommendations.

2.3. Developing an Institutional Economics Framework

Following the concepts from the general literature review, our study adopts an institutional economics framework to delve deeper into the dynamics of the shadow economy in Lebanon. Within this framework, our approach is qualitative, focusing on synthesizing insights from existing research and contextualizing them within Lebanon’s socio-economic context.

Institutional economics examines how institutions, such as legal and regulatory frameworks, governance structures, and societal norms, shape economic behavior (Hodgson 1998; Dreher et al. 2009) Contemporary institutionalist thinking warns against excessive reliance on quantitative models, arguing that they often overlook the importance of institutions and fail to adequately address uncertainty. Instead, it advocates for a nuanced understanding of institutional dynamics and their impact on economic behavior and societal outcomes (McMaster 2012).

Given the significance of corruption, institutional quality, and regulations in influencing informal economic activities, this framework provides a pertinent lens through which to analyze the complex relationship between the formal and shadow economies (Murphy et al. 1993; Pluskota 2020).

The institutional economics approach allows us to explore the interactions between institutional factors and economic agents, shedding light on the complex interplay between formal regulations and informal practices within the Lebanese context.

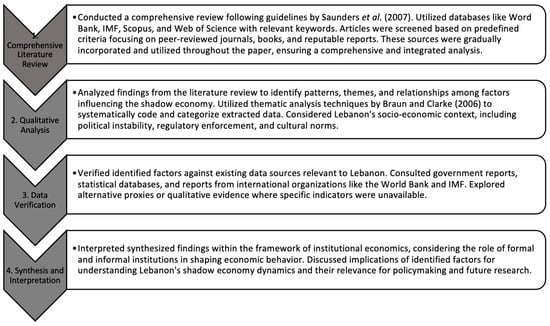

3. Methodology

The methodology of this paper follows the structure represented in Figure 3, where the main body is organized by themes and topics derived from the literature review. Initially, we conducted a comprehensive review of existing literature to identify general factors, causes, and indicators related to the shadow economy. Subsequently, we focused on analyzing the applicability of these variables to the context of Lebanon. Through this approach, we aimed to provide a synthesized overview of the dynamics of the shadow economy in Lebanon, informed by insights gleaned from previous research and verified against reliable data sources.

Figure 3.

Study methodological steps (Saunders et al. 2007; Braun and Clarke 2006).

Inclusion criteria for the comprehensive literature review focused on peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and reputable reports published in English that are directly relevant to the shadow economy, corruption, and the formal economy internationally and with a particular emphasis on Lebanon or similar economies. Exclusion criteria eliminated nonpeer-reviewed articles, opinion pieces, and studies that were not available in full text. While some sources were accessed before this period, the primary search process for the review was conducted over an extended timeframe from January to June 2024. This comprehensive period included a meticulous evaluation of titles, abstracts, and full texts of eligible articles to ensure their relevance and quality for inclusion in this paper. In more details, throughout the paper, in addition to reliable sources like the World Bank, IMF, and BDL, we identified references indexed in Scopus and Web of Science or both databases.

Furthermore, a significant addition to the methodology is the incorporation of a case study related to Lebanon. This approach allows us to contextualize theoretical insights within the specific socio-economic conditions of Lebanon, thereby enhancing the relevance and applicability of our findings.

4. Indicators of Lebanon’s Informal Economy: Investigating Key Factors

A study conducted by Kareh (2020) utilized the monetary approach for the estimation and analysis of the shadow economy’s size and its ramifications within the context of Lebanon. The investigation spanned from 1998 to 2018 and revealed that the shadow economy constituted approximately 36.61% of the GDP during this period, as represented in Table 1. Notably, in 2018, tax evasion represented 30.04% of the shadow economy, a figure nearly equivalent to Lebanon’s budget deficit. These findings underscore the existence of a significant underground economy in Lebanon, primarily driven by substantial tax evasion and expansion of the informal public sector. Additionally, the surge in cash transactions within this economy can be attributed to the support extended to Syrian refugees by both local and international NGOs, as well as the facilitative measures adopted by various banks (Kareh 2020).

Table 1.

Lebanon shadow economy estimation from 1998 till 2018 (Kareh 2020).

Lebanon ranks among the most corrupted countries worldwide, according to the CPI barometer (Transparency International 2022), and due to a lack of data and transparency, estimating the size of the shadow economy in Lebanon became increasingly challenging after the onset of the crisis in 2019. Specifically, in 2019, Lebanon ranked 137th out of 180 countries with a CPI score of 28, reflecting significant corruption, and by 2022, its position worsened to 150th with a CPI score of 24, indicating continued and severe corruption challenges.

The presence of multiple exchange rates further complicated the estimation process. As of 2021, the World Bank estimated that the cash economy in Lebanon was valued at approximately $10 billion, constituting over 45% of the country’s GDP (World Bank Group 2021a). This estimation reflects data up to the end of 2021. By early 2023, the situation continued to be dire, with ongoing economic instability affecting accurate assessments and projections (World Bank 2023a).

Estimating the volume of Lebanon’s informal economy is challenging due to the lack of reliable data. Medina and Schneider (2018), in their analysis of 157 shadow economies, mentioned that their model did not fully account for the significant influxes of refugees, potentially leading to underestimations of shadow economies in countries like Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, or Turkey. Additionally, since the war in Syria, the number of refugees in Lebanon has significantly increased, with the government registering 1.5 million refugees, making Lebanon the country with the “highest number of refugees per capita in the world” (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations 2023).

Considering so, examining the extent and dynamics of Lebanon’s shadow economy is essential given the country’s distinct socio-political and economic circumstances, marked by political discord, civil turmoil, security issues, and a substantial influx of refugees. Furthermore, Lebanon’s economic downturn, compounded by corruption, fiscal mismanagement, and currency devaluation, highlights the critical importance of comprehending the impact of informal economic practices on Lebanon’s economic structure and societal welfare.

We will explore the indicators of the informal economy in Lebanon by narrowing our focus to key determinants previously identified in Section 2 of the literature review that positively influence the shadow economy. These factors include the taxation system, regulatory decisions facilitating smuggling, currency circulation, fiscal deficit, and fostering the expansion of informal economic activities. Furthermore, we will also consider the downturn in GDP and employment levels.

4.1. Higher Unemployment and Lower GDP per Capita

Lebanon has a long history of political tensions, regional unrest, civil wars, and security challenges. Furthermore, corruption, U.S. sanctions, and the presence of political parties designated as “terrorists” by the international community have contributed to budget deficits and an enormous public debt (Azar and Abdallah 2019). These conditions, coupled with financial engineering that drained the market and commercial banks of foreign currencies, resulted in significant losses for the central bank and increased bank exposures to sovereign risk. The situation deteriorated in 2019, with banks raising interest rates to approximately 10% on foreign currency deposits (even higher for local currency) to attract new flows of foreign currency (Banque du Liban (BDL) 2023b). However, due to a lack of trust, banks faced a liquidity crisis and implemented unofficial capital controls, preventing depositors from withdrawing their funds. This led to a rapid devaluation of the currency, with the market exchange rate reaching approximately 42,000 LBP/USD by the end of 2022 (after being pegged at 1500 LBP/USD since the 1990s), resulting in business closures and significant negative changes in the country’s economic indicators between 2019 and 2021.

During this period, Lebanon’s GDP contracted by 50%, as shown in Figure 1 (World Bank 2023b), while the unemployment rate increased from 11.4% to 29.6% (Azzi 2022). The inflation rate also rose from 3% to 154.9% (World Bank Group 2021b), and the poverty rate increased from 28% to over 55%. A survey conducted by the Central Administration of Statistics in 2022 revealed that around 49% of unemployed individuals had been searching for work for more than one to two years (Baff 2022). These statistics indicate the significant economic challenges facing Lebanon.

4.2. Tax Rates in Lebanon

The taxation system poses a significant challenge to the Lebanese economy, heavily relying on indirect taxation, including value-added taxes, excise taxes, and tariffs, which account for a substantial portion of total revenues. These indirect taxes are regressive in nature, disproportionately affecting the middle class and the poor. In comparison to other countries, Lebanon has a very low share of revenues collected through a progressive tax scheme, with only around 11% of taxes being levied progressively on wages, property income, and inheritance. This is significantly lower than comparative countries, where the share of progressive taxes is two to three times higher. The taxation of personal income in Lebanon is based on a separate rate for each income source, resulting in an archaic system (Azzi 2022).

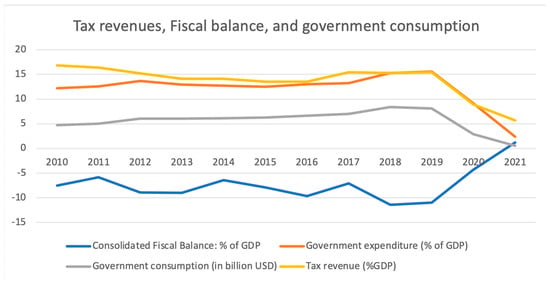

Lebanon’s tax system includes progressive rates for labor and rental income, while other categories such as capital gains and dividends are taxed at flat rates. However, the revenue from all types of income taxes is relatively low, accounting for 2.7% of GDP (refer to Figure 4). Corporate profit is taxed at a flat rate of 17%, representing a low share of total revenues. Inheritance and gift taxes are progressive, but their revenue is low, amounting to 0.2% of GDP. Real estate registration fees are flat at 5% of the property value and contribute to 1% of GDP. Lebanon lacks taxes that promote public goods such as environmental protection or regional development (Bifani et al. 2021).

According to the study by Bifani et al. (2021), Lebanon has low tax rates compared to other countries, but tax revenues are significantly lower due to widespread tax leakages and inefficiencies in tax collection. The compliance gap for value added tax (VAT) and lost customs revenue at the border are estimated to be around 3.3% and 1% of GDP, respectively. Banking secrecy laws hinder tax collection from liberal professions and capital gains earned abroad, and there are exemptions and loopholes in the inheritance tax system. These leakages have a regressive nature, as direct taxes are more rigorously assessed for low-income taxpayers, while wealthier taxpayers have more opportunities for tax avoidance. Reforms are needed to improve tax collection, including addressing banking secrecy, exemptions, and loopholes, and making the tax system more progressive (Azzi 2022).

The challenges posed by Lebanon’s taxation system, highlighted in Section 4.2, are compounded by significant fiscal losses and budget deficits, as discussed in the next section.

4.3. Fiscal Losses and Budget Deficits

From 2010 to 2022, Lebanon faced significant fiscal challenges characterized by fluctuations in its fiscal balance, government spending, and consumption amid economic instability. The fiscal balance varied markedly, with deficits reaching a peak in 2018 at −11.38% of GDP (Trading Economics 2023), pointing to unsustainable fiscal practices and the government’s dependency on public debt and in financial engineering that drained the foreign reserves from the banks in Lebanon (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2019; Azar and Abdallah 2019). A temporary fiscal balance improvement in 2021, at 1.2% of GDP, reflected drastic government spending cuts rather than genuine fiscal health. Government expenditure trends further illustrated the fiscal strain, with spending cuts in 2021, severely impacting social services and infrastructure and exacerbating economic contraction and social unrest (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2023). Lebanon’s fiscal experience from 2010 to 2022 emphasizes the critical need for structural reforms to achieve fiscal stability, reduce income inequality, and ensure economic and social well-being.

Figure 4.

Fiscal balance and government expenditures (authors’ compilation of data from Trading Economics 2023).

The financial crisis, exacerbated by fiscal challenges and taxation inefficiencies, amplifies the impact of smuggling activities in Lebanon, which contributes to the growth of the shadow economy and further strains the formal economy.

4.4. Financial Crisis and Smuggling in Lebanon

The smuggling relationship between Lebanon and Syria has a long-standing history, with around 150 illegal exchange points across the border (Daher 2022). In recent years, smuggling activities have taken on new dynamics, especially since the onset of the 2019 crisis. The most profitable among these activities is the smuggling of fuel oil from Lebanon to Syria, which occurred between October 2019 and October 2021 (LBCI Lebanon 2022).

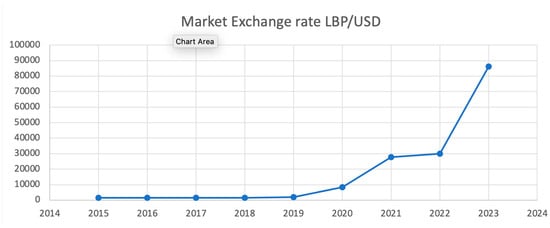

The fuel price was much cheaper in Lebanon, being subsidized at a low official rate of 1500 LBP/USD, while the market rate was several times higher in both Lebanon (as represented in Figure 5) and Syria due to the ongoing crisis. Hezbollah oversees the illegal crossing points on the Syrian-Lebanese border, allowing them to regulate the flow of goods and relying on local actors on the Syrian-Jordanian border for their smuggling activities (Daher 2022).

Figure 5.

Market exchange rate in Lebanon (graph created by the authors using data from Lirarate 2023).

A study funded by the European Union and conducted by Daher (2022) suggests that Hezbollah, along with Lebanon’s top political parties, has ties to customs and port officials that allow them to ship and receive their own cargos, resulting in an estimated loss of one to two billion dollars each year due to the evasion of customs duties. Corruption is prevalent at the port, with employees at every level, as well as state security officers, receiving bribes to speed up shipments, lower the value of imports, or avoid inspections.

In addition to fuel smuggling, other activities, such as the illegal trade of subsidized goods, tobacco, and drugs, also contribute to the growth of the shadow economy. Smuggling networks exploit the country’s weak borders, corrupt officials, and the desperate economic situation to carry out their operations, further straining the formal economy and exacerbating the financial crisis in Lebanon (Daher 2022).

Section 4.5 discusses the financial crisis that has led to a surge in cash transactions and cash in circulation, exacerbating liquidity challenges and raising concerns about tax enforcement, money laundering, and terrorist financing.

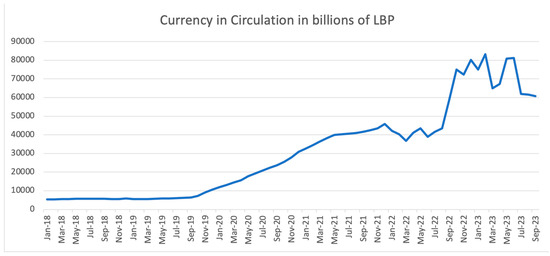

4.5. Amount of Cash in Circulation

Banks in Lebanon imposed severe restrictions on accessing depositor foreign currency accounts, converting deposits to Lebanese pounds (LBP) upon withdrawal. Consequently, the volume of cash in circulation surged significantly from LBP 6474 billion in September 2019 to LBP 80,171 billion by December 2022 (Banque du Liban (BDL) 2023a) (Figure 6). This surge stemmed from various factors, including depositor distrust in the banking system, rapid currency depreciation, and regulatory directives prompting depositors to convert foreign currency holdings into LBP. These developments exacerbated the liquidity crisis and underscored the challenges confronting Lebanon’s financial stability and broader economic framework.

Figure 6.

Fluctuation in currency in circulation in billions of LBL from January 2018 to September 2023 (graph created by the authors using data from Banque du Liban (BDL) 2023b).

The cash-based economy in Lebanon has made it challenging to enforce taxes and has raised concerns about money laundering and terrorist financing. Western governments are also worried that illicit transactions may rise as cash transactions are harder to track. The U.S. Department of the Treasury has sanctioned several entities and individuals in Lebanon for compliance issues, which are expected to increase. Recently, a Lebanese money exchanger was sanctioned for alleged ties to Hezbollah, a heavily armed, Iran-backed group (Gebeily 2023).

4.6. Government and Central Bank Regulations

Government and central bank decisions have played a crucial role in shaping Lebanon’s economy. Preceding the 2019 crisis, Lebanon maintained a fixed exchange rate regime, pegging the Lebanese pound (LBP) to the US dollar (USD) at a rate of 1500 LBP/USD through financial engineering methods and unsustainable fiscal policies (Abdel Samad 2021). These included subsidies offered at artificially low official rates and the implementation of measures to support the fixed exchange rate system.

Amid Lebanon’s ongoing financial instability, exacerbated by a banking sector crisis, the Lebanese Central Bank responded by implementing various measures. These included utilizing foreign reserves, amounting to $1.5 billion, to fulfill Eurobond payments and provide subsidies for vital commodities like fuel, wheat, medicine, and food. In an effort to alleviate the shortage of foreign currency liquidity and shield consumers from inflation, the Central Bank introduced new subsidies and circulars (Banque Du Liban (BDL) 2024) concerning the withdrawal of foreign currencies. However, these decisions had unintended repercussions, including market distortion and ineffectiveness, primarily benefiting the affluent. For instance, the subsidies, pegged at an official rate of 1500 LBP/USD despite a market rate of around 30,000 LBP/USD, incentivized smuggling across the Syrian border and stockpiling by the privileged segment of the population (Nasrallah 2020). Additionally, these policies gave rise to a novel currency phenomenon, the “Lollar”, symbolizing the trapped US dollars within Lebanon’s banking system.

The “Lollar”, a term coined during Lebanon’s banking crisis, represents the devaluation of US dollar-denominated bank accounts due to circulars issued by the Lebanese Central Bank (Helou 2022). These circulars implied that accounts in foreign currency were no longer valued at their nominal worth, leading to the emergence of the Lollar as a new currency standard. As inflation surged alongside the black-market exchange rate, the purchasing power of individuals receiving Lebanese pounds declined, exacerbating poverty levels. The formula for calculating the real value of foreign currency accounts in Lollars demonstrated significant losses for depositors upon cashing their funds, with checks worth only a fraction of their nominal amount. The depreciation of the Lollar continued, with the cash value of a 1000 USD check plummeting to just 16% in January 2024, reflecting a substantial haircut on foreign currency accounts (Abdel Samad 2021).

5. Results and Discussion

Understanding the dynamics of Lebanon’s informal economy is crucial amidst its socio-political instability and economic challenges. This section presents the results of our literature review and analysis, highlighting key factors contributing to Lebanon’s shadow economy and discussing their implications.

5.1. Key Factors Identified

Through a comprehensive analysis of various indicators, several critical factors influencing Lebanon’s informal economy have been identified. Table 2 examines the indicators linked to Lebanon’s informal economy, shedding light on its implications. Each factor is analyzed along with its underlying reasons and how they align with the institutional economics framework, providing insights into the institutional context shaping informal economic activities in Lebanon.

Table 2.

Summary of causes and indicators related to Lebanon’s informal economy.

In the labyrinth of Lebanon’s economic landscape, several intertwined factors perpetuate the shadow economy, leaving a trail of consequences. Among these, poor institutional quality acts as a catalyst, fostering an environment ripe for tax erosion and corruption (Svensson 2003). These elements, in turn, fuel the shadow economy, characterized by a web of informal activities, including smuggling. This cycle exacerbates Lebanon’s economic woes, contributing to budget deficits and widening income disparities. Similarly, understanding the role of leadership and organizational culture in managing economic uncertainties within organizations, as highlighted in a recent study by Oliveira et al. (2022), underscores the importance of strategic management practices in mitigating systemic risks and fostering organizational resilience, thereby influencing broader economic outcomes. Importantly, these issues are not solely macroeconomic in nature but also manifest at the organizational and institutional levels. Critically analyzing Lebanon’s case reveals the intricate relationship between institutional weaknesses and the proliferation of informal economic practices, highlighting the urgent need for structural reforms within the framework of institutional economics.

Our analysis revealed that the dynamics of Lebanon’s shadow economy are intrinsically tied to the country’s institutional framework.

5.2. Implications of Institutional Factors

Our study also unraveled the interconnectedness of these institutional factors and their adverse impact on Lebanon’s economy (refer to Figure 7). These interwoven challenges further amplify economic and financial risks and issues in Lebanon, including high unemployment rates, declining GDP, and currency instability.

Figure 7.

Main independent variables analyzed related to shadow economy and its impact in Lebanon (source: authors).

Our study reveals the intricate connections among institutional factors and their detrimental impact on Lebanon’s economy. These challenges exacerbate economic woes, including high unemployment, GDP decline, and currency instability. Our findings emphasize the urgency of addressing these issues due to their far-reaching consequences on economic stability, government revenues, and societal well-being.

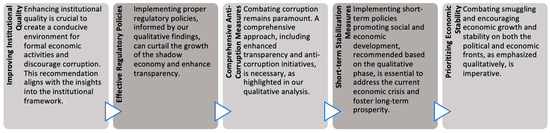

5.3. Addressing the Challenges

The current policies in Lebanon have proven ineffective in promoting sustainable development. To address these challenges, we recommend the following strategies, as mentioned in Figure 8:

Figure 8.

Recommendations to achieve long-term economic sustainability (source: authors).

5.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This research extends beyond theoretical insights, providing practical implications that can guide policymaking and real-world solutions to the challenges posed by the shadow economy in Lebanon.

This research enhances our theoretical understanding by demonstrating how institutional weaknesses in Lebanon exacerbate the shadow economy, reinforcing theories that link poor governance to informal economic activities. The study also broadens the theoretical framework by integrating macroenvironmental factors, such as servitization and market conditions, to explain how external elements influence the shadow economy. The influence of servitization on firms’ foreign market entry mode decisions highlights the importance of macroenvironmental factors such as market attractiveness and institutional environment (Agnihotri et al. 2022), which are also critical in understanding and addressing the dynamics of the shadow economy. Additionally, the findings validate existing theories on corruption and tax evasion while suggesting refinements specific to Lebanon’s institutional failures.

Practically, the study provides actionable recommendations for policy improvements, including enhanced regulatory frameworks, better tax collection mechanisms, and comprehensive institutional reforms. It also highlights the need for strategic management practices within organizations to mitigate risks associated with the informal sector. These insights offer valuable guidance for policymakers and can be applied to other similar economies, facilitating informed decision-making and comparative analysis.

6. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research Avenues

Our study sheds light on the complex dynamics of Lebanon’s shadow economy amidst pervasive socio-political instability and economic challenges. Table 2 meticulously examines key indicators and underlying causes associated with Lebanon’s informal economy, providing a nuanced understanding of its implications within the institutional economics framework.

The findings underscore the critical need for integrated strategies to combat the shadow economy, emphasizing the role of institutional quality, corruption dynamics, and regulatory frameworks in shaping informal economic activities. These insights not only deepen our comprehension of Lebanon’s economic landscape but also contribute theoretically by establishing a robust framework for future research in similar contexts globally. By integrating concepts of risk management and financial resilience, our study lays a foundation for developing effective strategies to mitigate the risks associated with informal economic practices.

6.1. Policy Implications

Given the significant risks posed to economic development by the shadow economy, our study emphasizes the urgent need for evidence-based policies that strengthen regulatory frameworks, combat corruption, and promote formalization. Implementing these measures is crucial for enhancing economic stability and fostering sustainable development.

To effectively tackle the shadow economy, policies should encompass several critical areas. Enhancing regulatory frameworks is essential, which involves developing and enforcing robust regulations to combat tax evasion, smuggling, and other informal activities, along with improving transparency in financial transactions and strengthening anti-corruption measures. Fighting corruption requires the establishment of independent bodies with the authority to investigate and prosecute corrupt practices and increasing transparency in public procurement and government spending. Encouraging formalization can be supported by several decisions like simplifying business registration processes, reducing bureaucratic barriers, and providing incentives such as tax breaks or subsidies for businesses transitioning to the formal sector. Strengthening financial sector oversight involves bolstering the capabilities of regulatory authorities to manage financial risks associated with informal activities. Fostering public-private partnerships is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the shadow economy, with industry leaders contributing to best practices for compliance and transparency. Additionally, investing in economic diversification through technology and sustainable industries can create new formal job opportunities and reduce dependence on informal sectors. Importantly, governance reforms are vital, as highlighted by Abou Ltaif and Mihai-Yiannaki (2024), which emphasize addressing political patronage and strengthening institutional frameworks to foster long-term economic stability and development in Lebanon.

6.2. Executive Implications

Managers and industry leaders can derive practical insights from our findings by enhancing transparency and compliance within their organizations. Mitigating risks linked to informal economic activities necessitates rigorous risk management frameworks and adherence to ethical business practices. Embracing sustainable finance practices can further enhance organizational resilience and stakeholder trust amid economic uncertainties.

6.3. Future Research

Future research should build upon our macroeconomic analysis by investigating additional factors that influence the shadow economy. An initial focus should be on exploring macroeconomic elements such as foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, national income disparities, regulatory environments, and economic stability, which play a significant role in shaping informal economic activities. Following this, integrating microeconomic factors will provide valuable insights into how corporate finance strategies, capital structure optimization, and sustainable finance practices impact and interact with the shadow economy. Understanding these microeconomic dimensions can reveal how company-level decisions and practices contribute to the persistence of the shadow economy, thereby informing more targeted and effective policies, reforms, and economic decisions. This comprehensive approach will enhance our understanding of the shadow economy’s dynamics and support the development of strategies to mitigate its adverse effects on economic stability and growth.

6.4. Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, our study not only provides valuable insights into Lebanon’s shadow economy but also offers practical implications and theoretical frameworks to inform policy interventions and academic inquiry globally. By bridging theory with actionable recommendations, we aim to catalyze efforts towards building more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable economies worldwide. This collaborative endeavor requires concerted efforts from academia, policymakers, and industry stakeholders to translate insights into impactful actions that promote economic stability, effective risk management, and equitable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.A.L.; methodology, S.F.A.L.; software, S.F.A.L.; validation, S.F.A.L., S.M.-Y. and A.T.; formal analysis, S.F.A.L.; investigation, S.F.A.L.; resources, S.F.A.L.; data curation, S.F.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.A.L.; writing—review and editing, S.F.A.L., S.M.-Y. and A.T.; visualization, S.F.A.L., S.M.-Y. and A.T.; project administration, S.F.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with no external funding or support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This paper is based on original research conducted by the author in accordance with ethical principles and standards set by the journal. The author has no conflicts of interest to declare, and the accuracy of the data and unbiased analysis and interpretation are affirmed.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Abdel Samad, Maher. 2021. Understanding the 2019–2020 Banking and Financial Crisis in Lebanon. Undergraduate thesis, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/49263 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Abou Ltaif, Samar, and Simona Mihai-Yiannaki. 2024. Exploring the Impact of Political Patronage Networks on Financial Stability: Lebanon’s 2019 Economic Crisis. Economies 12: 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, Susan-Rose. 1997. Corruption, inefficiency and economic growth. Nordic Journal of Political Economy 24: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, Arpita, Saurabh Bhattacharya, Natalia Yannopoulou, and Alkis Thrassou. 2022. Foreign market entry modes for servitization under diverse macroenvironmental conditions: Taxonomy and propositions. International Marketing Review 40: 561–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, Samile Antoine, and Khaled Abdallah. 2019. What drives the accretion of the foreign exchange reserves of the Lebanese Central Bank? (1994–2018). Theoretical Economics Letters 9: 633–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, Aline. 2022. Tax System in Lebanon: Insufficient, Un-Equalizing, and Leaky! Blominvest Bank. Available online: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/43044/tax-system-in-lebanon-insufficient-un-equalizing-and-leaky/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Baff, Sam. 2022. CAS-ILO: Unemployment Is at 29.6% and Youth Unemployment at 47.8% in Lebanon by January 2022. Blominvest Bank. Available online: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/44347/cas-ilo-unemployment-is-at-29-6-and-youth-unemployment-at-47-8-in-lebanon/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Banque du Liban (BDL). 2023a. Banque du Liban. Available online: https://www.bdl.gov.lb/economicandfinancialdatasub.php?docId=17&code=1&filecode=100 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Banque du Liban (BDL). 2023b. Banque du Liban. Available online: https://www.bdl.gov.lb/statisticsandresearch.php (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Banque Du Liban (BDL). 2024. Available online: https://www.bdl.gov.lb/intermediatecirculars.php?tpages=46&page=2&langid=EN (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Berdiev, Aziz N., Rajeev K. Goel, and James W. Saunoris. 2018. Corruption and the shadow economy: One-way or two-way street? The World Economy 41: 3221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifani, Alain, Karim Daher, Lydia Assouad, and Ishac Diwan. 2021. Which tax policies for Lebanon? Arab Reform Initiative. May 28. Available online: https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/which-tax-policies-for-lebanon-lessons-from-the-past-for-a-challenging-future/ (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Blanton, Robert G., and Dursun Peksen. 2021. A global analysis of financial crises and the growth of informal economic activity. Social Science Quarterly 102: 1947–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, Phuc Nguyen, Christophe Schinckus, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2021. What Are the Drivers of Shadow Economy? A Further Evidence of Economic Integration and Institutional Quality. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 30: 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chletsos, Michael, and Andreas Sintos. 2024. Political Stability and Financial Development: An Empirical Investigation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 94: 252–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jay Pil, and Marcel Thum. 2005. Corruption and the shadow economy. International Economic Review 46: 817–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, Adeline-Cristina, Corina-Narcisa (Bodescu) Cotoc, Viorela Ligia Vaidean, and Monica Violeta Achim. 2021. Corruption, Shadow Economy and Deforestation: Friends or Strangers? Risks 9: 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, Joseph. 2022. Lebanon: How the Post War’s Political Economy Led to the Current Economic and Social Crisis. Available online: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/73856/QM-01-22-031-EN-N.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Dreher, Axel, and Friedrich Schneider. 2010. Corruption and the Shadow Economy: An Empirical Analysis. Public Choice 144: 215–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, Axel, Christos Kotsogiannis, and Steve McCorriston. 2009. How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance 16: 773–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. 2023. Lebanon. European Commission. Available online: https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/where/middle-east-and-northern-africa/lebanon_en (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Friedman, Barry A. 2014. The relationship between effective governance and the informal economy. International Journal of Business and Social Science 5: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeily, Maya. 2023. Cash is king in Lebanon as banks atrophy. Reuters. January 31. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/markets/cash-is-king-lebanon-banks-atrophy-2023-01-31/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Gemayel, Fouad. 2023. What the trade balance reveals about Lebanon in 2022. L’Orient Today. February 1. Available online: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1326676/what-the-trade-balance-reveals-about-lebanon-in-2022.html (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Helou, Joseph P. 2022. State collusion or erosion during a sovereign debt crisis: Market dynamics spawn informal practices in Lebanon. In Informality, Labour Mobility and Precariousness: Supplementing the State for the Invisible and the Vulnerable. Edited by Abel Polese. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 1998. The Approach of Institutional Economics. Journal of Economic Literature 36: 166–92. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2019. Lebanon IMF Executive Board Concludes 2019 Article IV Consultation. IMF. October 17. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/10/17/pr19378-lebanon-imf-executive-board-concludes-2019-article-iv-consultation-with-lebanon (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2023. General Government Gross Debt. IMF.org. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GGXWDG_NGDP@WEO (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Kanniainen, Vesa, Jenni Pääkkönen, and Friedrich Schneider. 2004. Determinants of Shadow Economy: Theory and Evidence, Discussion Paper. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/21383082/Determinants_of_shadow_economy_theory_and_evidence (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Kareh, Marie D. 2020. The reform of the tax system in Lebanon: An impossible equation? In Economics and Finance. Paris: Université Panthéon-Sorbonne—Paris I. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer-Mbula, Erika, and Sascha Wunsch-Vincent, eds. 2016. Introduction. In The Informal Economy in Developing Nations: Hidden Engine of Innovation? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPorta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny. 1999. The Quality of Government. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 15: 222–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LBCI Lebanon. 2022. Smuggling from Lebanon to Syria Puts Country under Additional Stress. LBCIV7. December 28. Available online: https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/press/679889/lbci-lebanon-articles/en (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Lirarate. 2023. Lira Rate | USD to LBP in Black Market | Dollar to LBP. Lira Rate. Available online: https://lirarate.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- McMaster, R. 2012. Institutional economics: Traditional. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home. Edited by Susan J. Smith. San Diego: Elsevier, pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Medina, Leandro, and Friedrich Schneider. 2018. Shadow Economies around the World: What Did We Learn over the Last 20 Years? IMF Working Papers. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, vol. 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchuk, Halyna, Svitlana Bilan, Halyna Yurchyk, Liudmyla Akimova, and Mykolas Navickas. 2020. Impact of the shadow economy on social safety: The experience of Ukraine. Economics & Sociology 13: 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Kevin M., Andrei Shleifer, and Rober W. Vishny. 1993. Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth? American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 83: 409–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah, Tala. 2020. BDL Issues Circulars Related to Provisioning Banks and Financial Institutions Subsidized Trade Finance Transactions and to Withdrawals of USD Deposits. Blominvest Bank. October 15. Available online: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/38340/bdl-issues-circulars-related-to-provisioning-banks-and-financial-institutions-for-specified-trade-transactions-and-to-withdrawals-of-usd-deposits/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Nguyen, Giang Ngo Tinh, and Xianmin Liu. 2023. The interrelationship between corruption and the shadow economy: A perspective on FDI and institutional quality. Journal of Economics and Development 25: 349–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Margarida Freitas, Eularia Santos, and Vanessa Ratten. 2022. Strategic perspective of error management, the role of leadership, and an error management culture: A mediation model. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science 28: 160–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuc Canh, Nguyen. 2018. The effectiveness of fiscal policy: Contributions from institutions and external debts. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 25: 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluskota, Anna. 2020. The impact of corruption on economic growth and innovation in an economy in developed European countries. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sectio H Oeconomia 54: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, Suzan. 1999. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Eularia, and Fernando Oliveira Tavares. 2020. The level of knowledge of financial literacy and risk of the Portuguese. International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 13: 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Mark, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2007. Research Methods for Business Students. London: Financial Times/Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Frederich. 2000. The Increase of the Size of the Shadow Economy of 18 OECD Countries: Some Preliminary Explanations. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 306. Munich: CESifo. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Friedrich. 2005. Shadow economies around the world: What do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy 21: 598–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Andreas Buehn. 2016. Estimating the Size of the Shadow Economy: Methods, Problems, and Open Questions. IZA Discussion Paper 9820. Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/9820/estimating-the-size-of-the-shadow-economy-methods-problems-and-open-questions (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Dominik Enste. 2000. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipov, Ilkhom. 2015. Contemporary Economic Growth Models and Theories: A Literature Review. CES Working Papers. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/481724c8292a156a08131a686552e021/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2035671 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Statista. 2024. Lebanon—Budget Balance in Relation to GDP 2012–2022. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/455256/lebanon-budget-balance-in-relation-to-gdp/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Svensson, Jakob. 2003. Who must pay bribes and how much? Evidence from a cross section of firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, Vito. 1999. Uses and abuses of estimates of the underground economy. The Economic Journal 109: 338–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, Vito. 2002. The Shadow Economy, Its Causes, and Its Consequences. Lecture Given at the International Seminar on the Shadow Economy Index in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Institute of Ethics in Competition. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Fernando, Eulália Santos, Margarida Freitas Oliveira, and Luís Almeida. 2024. Determinants of Corporate Indebtedness in Portugal: An Analysis of Financial Behaviour Clusters. Risks 12: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, Benno, and Friedrich Schneider. 2009. The impact of tax morale and institutional quality on the shadow economy. Journal of Economic Psychology 30: 228–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trading Economics. 2023. Lebanon Government Budget. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/lebanon/government-budget (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Transparency International. 2022. Corruption Perceptions Index 2021. February 3. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- World Bank. 2023a. Lebanon: Normalization of Crisis Is No Road to Stabilization. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/05/16/lebanon-normalization-of-crisis-is-no-road-to-stabilization (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- World Bank. 2023b. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- World Bank Group. 2021a. GDP Growth (Annual %)—Lebanon. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2020&locations=LB&start=2005 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- World Bank Group. 2021b. Lebanon Economic Monitor: Lebanon Sinking to the Top-3. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lebanon/publication/lebanon-economic-monitor-spring-2021-lebanon-sinking-to-the-top-3 (accessed on 29 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).