2. Methods

In order to evaluate the financial sustainability of PAYG pension systems, it is necessary to compare the evolution of pension expenses and contributions for retirement over the long term. In the absence of microdata about the contribution history of salaried workers, which is our case, it will be difficult to accurately predict the number of retirees among people of retirement age as well as the corresponding amounts of pension benefits and to estimate the future evolution of pension expenses. For this, we follow the methodology used in

Flici and Planchet (

2020) and

Flici (

2023) to project retirement expenses and contributions in the future. The methodology consists of considering all people at working age as potential contributors with a specific probability and all people reaching retirement age as potential retirees with an expected duration of contribution, estimated based on the evolution of the probability to contribute to retirement over the duration of working age.

To predict the future evolution of the total contribution for retirement paid by salaried workers, two pieces of information are needed: the evolution of the population of contributors and the evolution of the average yearly amount of contribution to retirement . This can be written as follows: . The population of contributors at age in the year is obtained by multiplying the global population by age by the age-specific probability of contribution to retirement as a salaried worker ; this leads to . This probability takes into consideration employment rates, salaried employment rates, and rates of affiliation to social security among salaried workers. On the other hand, the evolution of the average amount of the yearly contribution to retirement ( is estimated based on wage evolution in time and age ( and the contribution rate for retirement . We can write this as follows: .

To move from the contribution phase to the pension payment phase,

Flici and Planchet (

2020) adapted the concept of the ‘expected duration of contribution (

)’, which can be obtained by summing up the age-specific probabilities to contribute to retirement as a salaried worker over the duration of the working career. For a retirement age

in year

the expected duration of contribution can be calculated as follows:

. The EDC was used to replace the duration of contribution in calculating the first pension benefit

, combined with the final wage

and the annuitization factor

. We could write the following:

. Then, pension benefits (

are augmented yearly to fit inflation. Usually, a rate of

is used. This leads to

. The total direct pension benefits paid for retirees during the year

, which we denote as

, is calculated by summing up the pension benefits paid for all the generations of retirees; with this latter being equal to the average pension benefit paid in the year

for retirees aged

multiplied by the corresponding population

, with

going from age

to the ultimate age of survival

. We can write

. In addition to direct benefits, survivors’ benefits are provided to parents, spouses, and orphans of the main retiree after their death. In our case, the total survivors’ pension benefits are calculated as a constant share of the

. According to recent observed values, this share was estimated at

(

Flici 2023). Hence, the total pension benefits

were calculated as follows:

. By adding

of administration fees, we obtained the total retirement expenditures

. We write

.

On the other hand, the multi-scenario analysis was performed considering all the variables assumed to have a direct effect on the financial balance of the retirement system. These variables can be arranged into two different sets of variables: environmental variables and possible reform actions (

Table 1).

Environment variables include population growth, employment, salaried employment, affiliation to social security as a salaried worker, wage evolution, and contribution collection factor. This set of variables was considered with three simplistic evolution scenarios (a central scenario inspired by current levels or recent trend, a high scenario, and a low scenario), except population growth, which was considered with fifteen scenarios. Environmental variables are assumed to vary according to simple scenarios of smooth and consistent progression along the projection horizon, with the values displayed in

Table 1 being those expected to be attained in 2070. The limitations of such a hypothesis are obvious, but it allows for an initial assessment of the effectiveness of contribution caps as a reform alternative. More sophisticated methods can be employed subsequently for a more in-depth and realistic analysis.

The possible reform actions, which are assumed to have an immediate effect, include raising the age of retirement, increasing the rates of contribution to retirement, reducing the annuitization rate, expanding the salary period base, and reducing pensions’ annual revaluation rate. Reform actions were considered with three options: ‘no change’, ’minor reform’, and ‘major reform’.

In order to assess the effect of capping the contributed salaries on enhancing the financial sustainability of Algeria’s retirement system, we consider four different cap levels: i. “No cap”, ii. 80%, iii. 60%, and iv. 40%. Under each capping level, we assess a total of 295,245 scenarios, crossing 3645 scenarios about the environment and 81 possible combinations of reform actions concerning the retirement parameters, all considered with 3 scenarios of no reforms, minor reforms, and major reforms. The detailed methodology of the multi-scenario analysis is explained in

Flici (

2023). By considering the four scenarios of capping levels, we had to assess a total of 1,180,980 scenarios.

Due to a lack of data about salaries, the distribution of wages is not made available in official statistics or in academic publications. What we do have is the evolution of salaries by large age intervals. In order to set up an easily understandable framework for our calculations, we assume all workers aged in year receive the same wage; the latter is assumed to grow with time and age. Setting age 20 to be the age of first entrance to the labor market in the year (t), an average worker is expected to receive a salary of , which corresponds to the minimum salary an average worker could receive during their entire working career. We assume, implicitly, an increasing salary evolution during a working career. Thus, the maximum wage is received during the last year before retirement. The range of salary evolution corresponds to the gap between early and late working career salary.

The evolution of salary by large age intervals is retrieved from the data of the household revenues survey administered by the Algerian Office of National Statistics [ONS] in 2011 (

ONS 2014). Then, a polynomial interpolation was used to estimate the evolution of the average salary at single ages. A similar methodology was used in

Flici and Planchet (

2020).

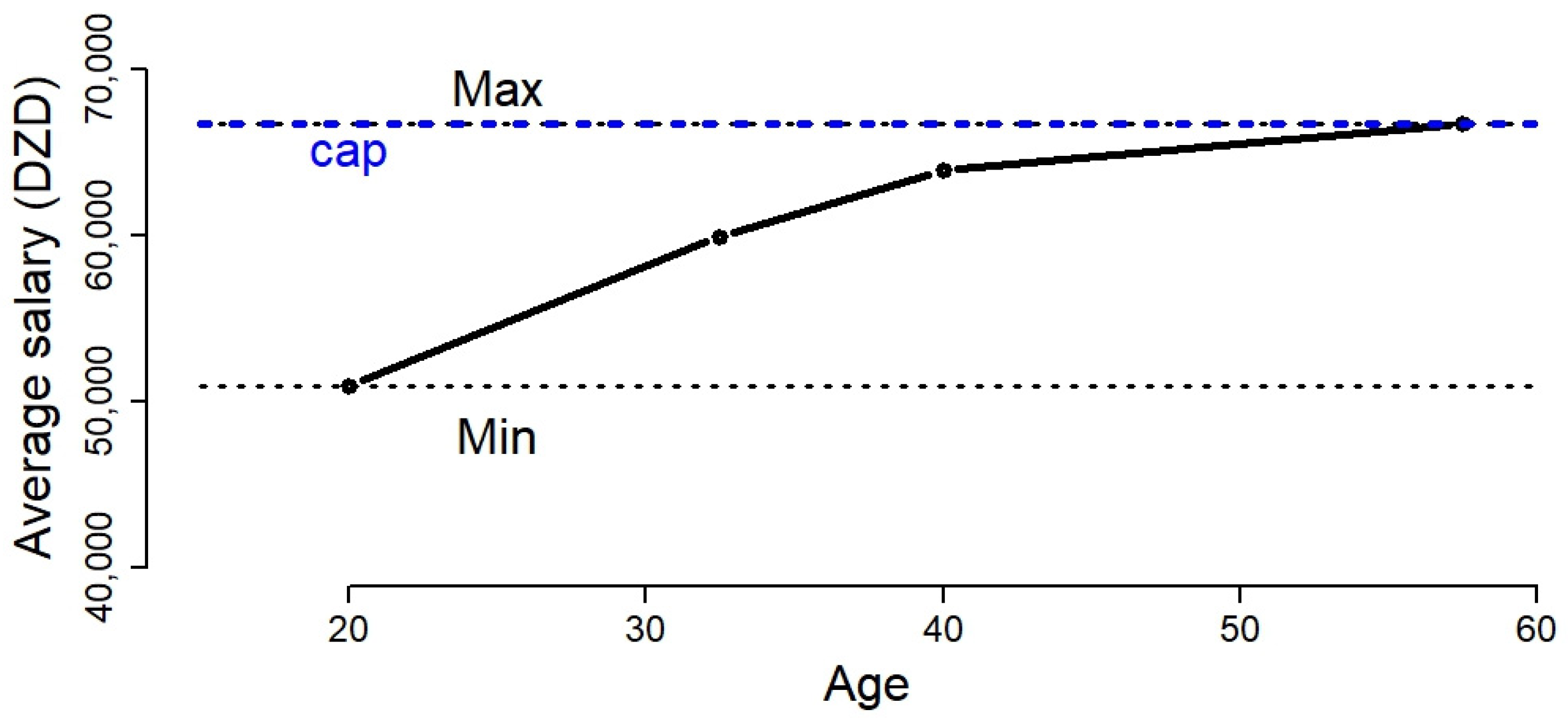

Considering the range of salary evolution during a working career, the contributed salary cap is set as a fraction of the minimum–maximum average salary range and is defined to be the limit above which a salary is not subject to contribution to social security (See

Figure 1). A contributed salary cap of 40%, for example, means that the cap is set at 40% from the range between minimum and maximum wages. The range from the minimum wage up to the cap is contributable, while the remaining range (i.e., from the cap to the maximum wage) is not.

For our analysis, we compare different capping levels (i.e., 100%, 80%, 60%, and 40%) and we analyze their impact on the financial balance of the Algerian retirement system up to 2070. The assessment methodology is similar to that proposed by

Flici and Planchet (

2020) and adapted later by

Flici (

2023).

The financial sustainability of retirement systems refers to future incomes being higher, or at least equal, to future expenses. Here, we use the incomes-to-expenses ratio (IER) as an indicator to assess sustainability. A value of 1 implies total income equalizing total expenses; a value of 0.5 means that retirement incomes cover half of the retirement expenses only; and so on.

Note that due to the unavailability of official statistics about employment, social security, salaries, and demography in Algeria after 2019, we use 2020 as the base-year for all projections.

3. Results

Figure 2 shows the obtained results. The left column displays the capping level, while the right-hand one displays the corresponding incomes-to-expenses ratio. The latter shows three layers of color starting from the light gray, which corresponds to major changes made to retirement parameters, namely retirement age, contribution rate, years of contribution used as a reference, and annuitization rate. The second layer, represented in dark gray, corresponds to minor changes made on the previously mentioned parameters combined with different combinations of the environmental variables. The third layer shown in gray reflects the “no reform” situation combined with all the possible environmental changes.

The results obtained with “no-cap” are similar to those obtained by

Flici (

2023) and suggest that in the most favorable environmental conditions combined with major parametric reforms, retirement incomes will not be enough to cover retirement expenses during the period up to 2070. Under the most favorable conditions, the ratio of incomes to expenses is expected to reach its peak in 2038–2039 with a value of 99.6%. Then, it decreases to around 80% during the 2057–2060 period, before increasing again and reaching 89% in 2070.

Essentially, introducing a contributed salary cap is supposed to help minimize the deficit; the lower the cap, the smaller the deficit. The primary objective of comparing various cap levels is to determine an adequate cap to alleviate the system’s long-term financial deficit. Compared to the no-cap situation, introducing a cap of 80% on the contributed salaries may allow an increase in the incomes-to-expenses ratio. Indeed, this later increased to slightly higher than 1 during the 2036–2040 period. Then, it decreased to around 81.5% in 2057–2059, and increased again to 90% in 2070.

The incomes-to-expenses ratio stands above 100% up to the year 2045, when a cap of 60% is applied to contributed salaries, but when the best environment conditions meet major parametric reforms. Afterward, this ratio is expected to decrease to 86% in 2057–2059 and increase again to 95.6% in 2070.

Lowering the cap further (i.e., 40%) results in positive balance for a longer time period, but if a very favorable environment happens and major parametric reforms are introduced, i.e., a retirement age of 65 and 62 years for men and women, respectively, an annuitization factor of 2% only, a salary base period of 12 years, and a contribution rate of 22%. The incomes-to-expenses ratio can reach a value of 111% during the 2038–2040 period. The lowest value that it can record is 91% in 2055–2060, while it is expected to rise back to 1 in 2069.

4. Discussion

Population aging is the most significant threat to the future sustainability of PAYG pension schemes. The rising share of the elderly in national populations forced many governments to implement substantial pension reforms. The experience of the last half-century has demonstrated that there are a few if any reform options that are—at the same time—economically feasible, efficient in ensuring long-term sustainability, and socially acceptable. The most recommended reform measures to save PAYG plans were the implementation of a multi-pillar system or the transition to a fully funded plan. Despite the fact that such reforms have encountered strong societal resistance in several countries, their effectiveness is not always guaranteed. Many reforms were followed by other reforms, or even reform reversals. Parametric reforms are another option that is more silent and less likely to draw social attention. The latter, when well-studied, can help achieve or improve financial sustainability while remaining socially acceptable.

Algeria is one of the countries that has already begun to experience the effects of population aging on pension plan sustainability (

Flici and Planchet 2020), with traditional parametric reforms failing to address the expanding deficit (

Flici 2023). Maintaining long-term sustainability will require more than simply delaying retirement, increasing contribution rates, or lowering replacement rates. Additional and stronger reform measures will be required.

One further action that can help reduce future deficits in the current circumstances of population aging and better target low earners is capping the share of the salary subject to contribution, also called the “contribution cap”. Our main idea was that accepting lower contributions from employees today will imply paying much lower benefits for them when they retire. This paper aimed to assess the feasibility of such an action as well as its efficiency in alleviating the deficit in Algeria’s pension system. We evaluated and compared different contribution caps, combined with different possible combinations of reform actions and environmental changes. Reform actions concerned postponing retirement age, increasing contribution rates, reducing the benefit conversion rates (replacement rate), and expanding the salary base period used in calculating benefits.

The proposed methodology allowed us to assess the effectiveness of the contribution cap as a supplement to traditional parametric adjustments in improving the long-term sustainability of Algeria’s pension plan in a changing socioeconomic environment. It also allowed us to assess whether a contribution cap may be used to substitute or supplement parametric reforms as a solution to population aging implications. The benefit of crossing multiple caps with multiple reform actions, all paired with multiple environmental scenarios, is that it allows for the assessment of sustainability conditions and the determination of whether a specific contribution cap level will help to ensure the system’s future sustainability, as well as the combination of parametric reforms and socioeconomic conditions.

Results showed that, globally, setting (or lowering) a contributable salary cap positively affects the evolution of the financial balance of the Algerian retirement system in the long-term. However, it was shown that, in the most favorable socio-economic environment changes (improvement in employment rates up 80% for men and 40% for women by 2070, more than 80% of salaried employment, enrollment rates higher than 80%, a collection factor of 95%, and 3% annual wage growth rate) and with the heaviest possible parametric reforms (a retirement age of 65 years for men and 62 for women, an annuity rate of 2%, a contribution rate of 22%, and a salary base period of 12 years), it will be challenging to completely eradicate the deficit from 2045 onwards. On the other hand, starting from a 60% cap, total contributions will significantly exceed total benefits from now to 2045, and for a 40% cap, in a good environment and with major parametric reforms, the projected excess from now to 2045 will be able to cover the deficit of the period from 2045 onwards. However, it will be necessary to find ways to save the excess of the first period to finance the deficit of the second period.

Such a result cannot be expected without major parametric reforms and favorable socio-economic conditions. Still, whatever the socio-economic environment is, setting a contributable salary cap will help improve the situation. However, such a kind of reform is not as silent as we imagine it to be. The workers who have already paid high contributions, especially those at the end of their working career, and who expect to receive high benefits at retirement will experience the largest losses and need to be compensated. This is a prerequisite to reduce social resistance and improve intergenerational equity (

Conde-Ruíz and González 2012), which is primordial for a successful reform.

The implementation of a contributable salary cap will leave an exploited saving effort for high earners (

Simonovits 2012) that will need to be addressed. To allow high earners to make more savings and increase their retirement income, a second pillar needs to be created, either under private or public management, PAYG or fully funded, and more importantly, less generous and actuarially more fair than the current system. One other solution can consist of introducing a threshold-based contribution system with different generosity degrees depending on salary slices. The bottom slice of salaries will—for example—benefit from high conversion rates; the second slice will be given moderate benefit rates; while the high salary range will receive less generous benefits. A simulation analysis can be performed to define the optimal salary thresholds with regard to the effect on the financial sustainability of the whole system.

One major limit of this work consists of assuming a smooth and steady evolution of the different variables affecting the sustainability of the pension system. Such an assumption seems to be unrealistic, because in the real world, demographic and economic variables can show ups and downs depending on many factors. We are aware of the impacts of such assumptions on sustainability assessment, but this can represent a first step towards more sophisticated scenario-based analyses. One other limit consists of not considering the interactive effect between the different variables involved in the financial sustainability of the pension system. It was simply assumed that all the variables are fully independent. For example, it was not considered that the reform actions will impact individuals’ behavior regarding social security enrollment or saving efforts. It was also not considered whether there was an interaction between the different environmental variables. For example, in the real world, increasing contribution rates is very likely to result in decreasing the rates of enrollment to social security; postponing the retirement age is likely to increase the workforce offer and lead to lower salary growth rates. Thus, the results presented here should be interpreted with caution. One other issue in this work relates to data availability, especially regarding salary distribution. To deal with such a data shortage, we used the evolution of the average salary by age instead of using the salary distribution to evaluate the implication of a contributable salary cap. This assumes that all workers at the same age, of any sex, receive the same salary in the same year, with this average salary increasing over age and time.