Asymptotic Expected Utility of Dividend Payments in a Classical Collective Risk Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equation

3. Asymptotic Analysis

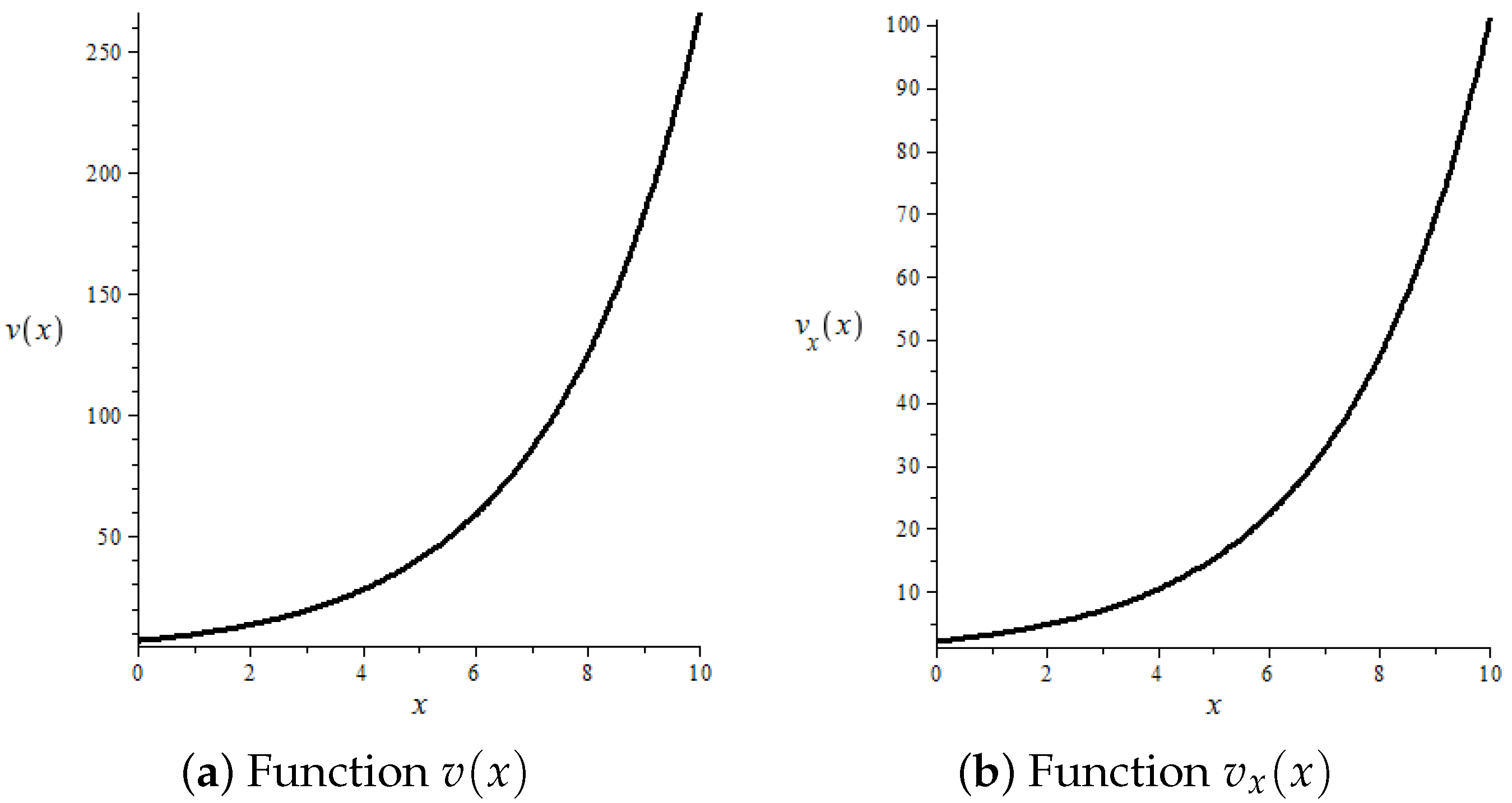

3.1. Classical Risk Process (1) and Power Utility Function

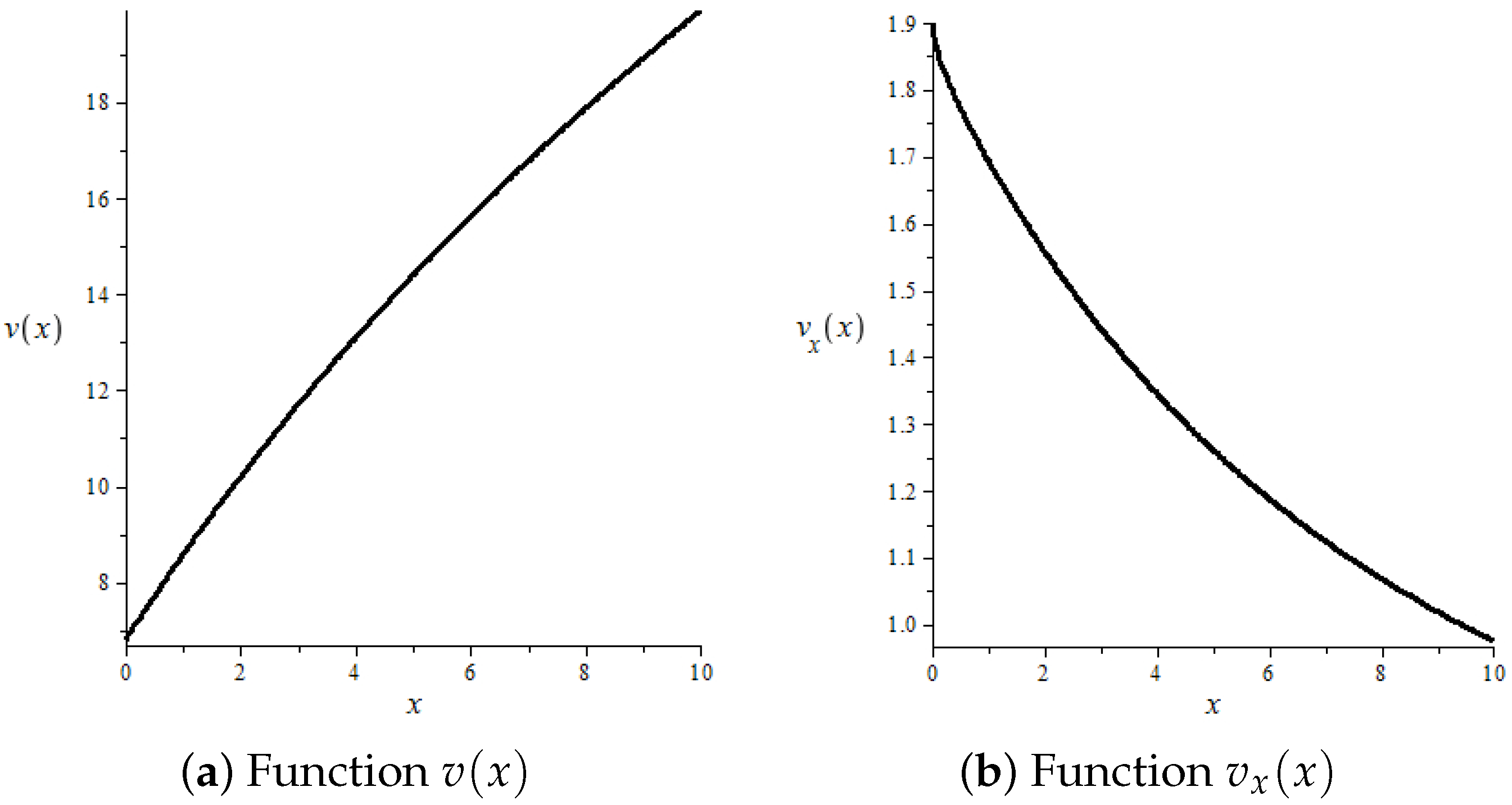

3.2. Classical Risk Process (1) and Logarithmic Utility Function

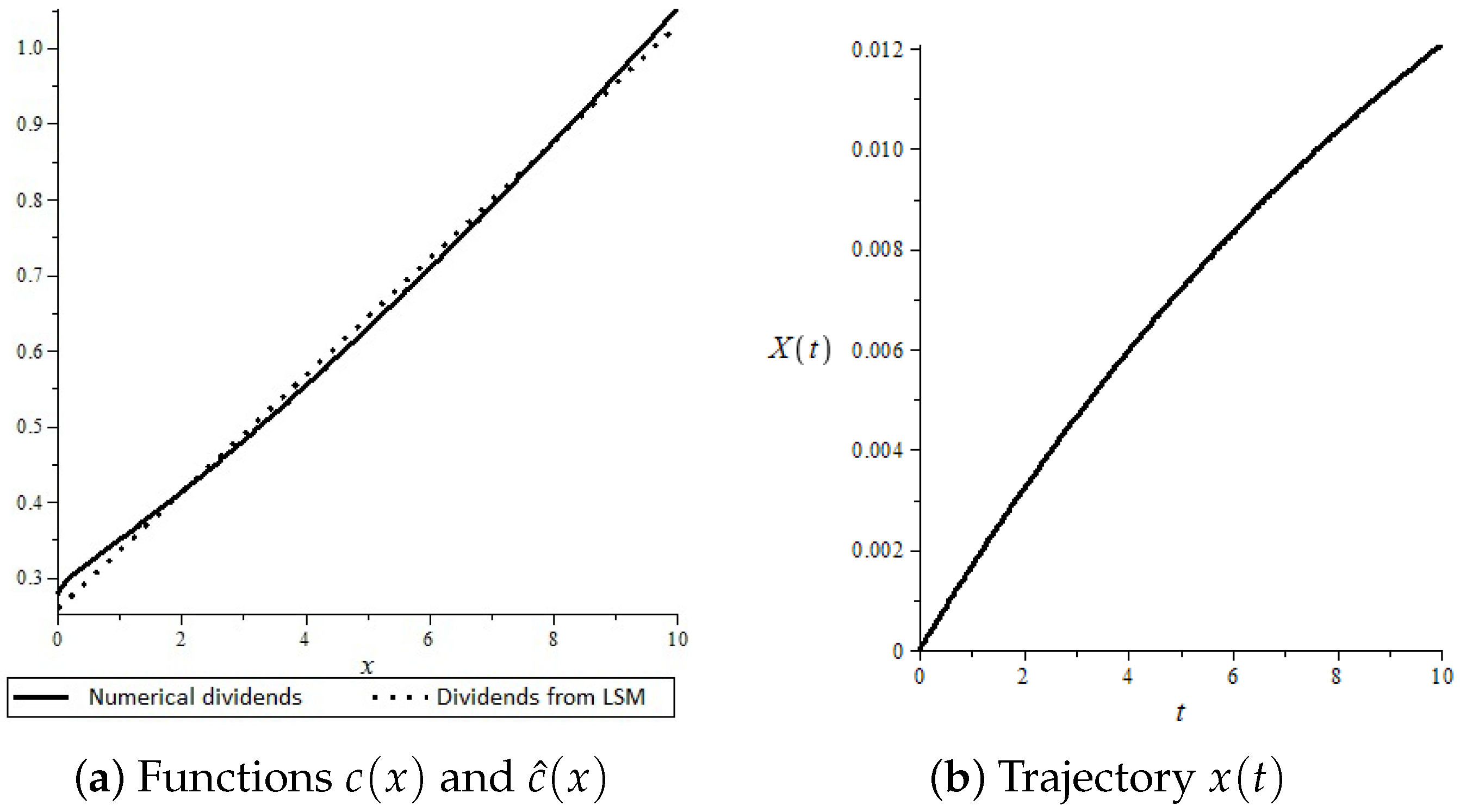

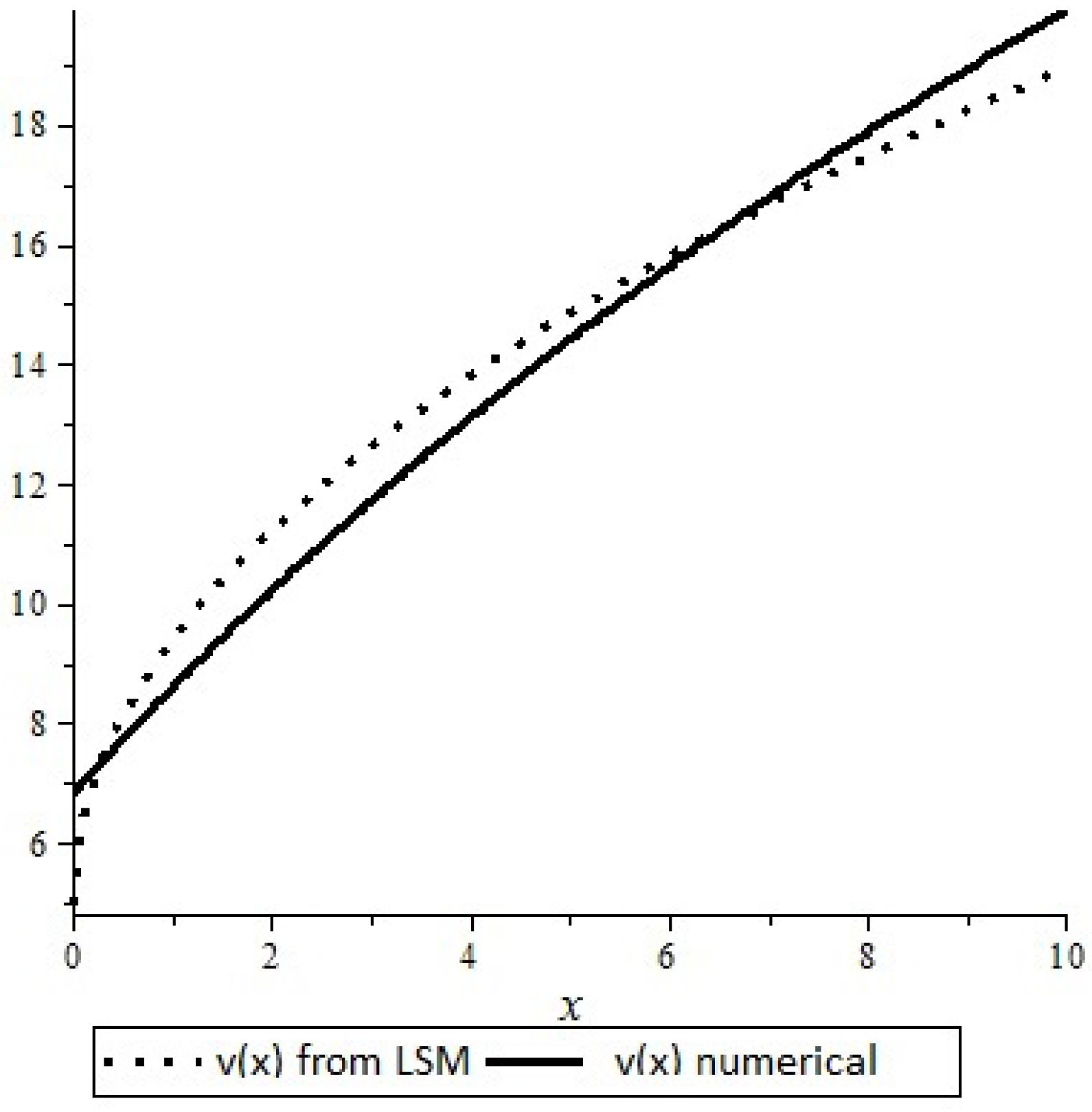

4. Numerical Analysis

- Set initial value ,

- From the equality (13) derive initial value ;

- Solve numerically the differential Equation (12) with the initial condition ;

- Calculate using ;

- Using the least squares method, approximate be the linear function . Because of our results from Theorem 2, we assume that is a linear function;

- Let be a trajectory of the regulated process starting from 0 until the first time claim arrival T. Hencei.e.,

- Using the least squares method, approximate by a function of the form . Because of our results from Theorem 2, we assume that is a power function;

- Calculatewhere .

- Calculate the value ;

- Repeat until for fixed .

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 2

- (a)

- and ;

- (b)

- and ;

- (c)

- and .

- I.

- If , then, via the separation of variables, we have

- II.

- If , then a simple integration leads to

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 3

- (a)

- and ;

- (b)

- and ;

- (c)

- and .

References

- Albrecher, Hansjörg, and Stefan Thonhauser. 2009. Optimality results for dividend problems in insurance. RACSAM Revista de la Real Academia de Ciencias, Serie A, Matematicas 103: 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, Soren, and Hansjorg Albrecher. 2010. Ruin Probabilities. Singapore: World Scientific Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen, Søren, and Michael Taksar. 1997. Controlled diffusion models for optimal dividend pay-out. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 20: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, Florin, Zbigniew Palmowski, and Martijn R. Pistorius. 2007. On the optimal dividend problem for a spectrally negative Lévy process. Annals of Applied Probability 17: 156–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, Florin, Zbigniew Palmowski, and Martijn R. Pistorius. 2015. On Gerber-Shiu functions and optimal dividend distribution for a Lévy risk-process in the presence of a penalty function. Annals of Applied Probability 25: 1868–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcue, Pablo, and Nora Muler. 2005. Optimal reinsurance and dividend distribution policies in the Cramér-Lundberg model. Mathematical Finance 15: 261–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, Sebastian, and Zbigniew Palmowski. 2013. Problem optymalizacji oczekiwanej użyteczności wypłat dywidend w modelu Craméra-Lundberga. Roczniki Kolegium Analiz Ekonomicznych 31: 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, Sebastian, and Zbigniew Palmowski. 2017. Optimal utility of dividends for Cramér-Lundberg risk process. Applicationes Mathematicae 44: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coddington, E. A., and N. Levinson. 1987. Theory of Differential Equations. New Delhi: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- De Finetti, B. 1957. Su un’impostazione alternativa dell teoria colletiva del rischio. Transactions of the XVth International Congress of Actuaries 2: 433–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, Julia, and Hanspeter Schmidli. 2011. Minimising expected discounted capital injections by reinsurance in a classical risk model. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 3: 155–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Julia, and Zbigniew Palmowski. 2021. Optimal dividends paid in a foreign currency for a Lévy insurance risk model. North American Actuarial Journal 25: 417–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Hui, and Chuancun Yin. 2023. A Lévy risk model with ratcheting and barrier dividend strategies. Mathematical Foundations of Computing 6: 268–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, Hans U. 2012. Introduction to Mathematical Risk Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published in 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, Hans U., and Elias S. W. Shiu. 2004. Optimal dividends: Analysis with Brownian motion. North American Actuarial Journal 8: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goldie, C., N. Bingham, and J. Teugels. 1989. Regular Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grandits, Peter, Friedrich Hubalek, Walter Schachermayer, and Mislav Žigo. 2007. Optimal expected exponential utility of dividend payments in Brownian risk model. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 2: 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanblanc-Picqué, Monique, and Albert Nikolaevich Shiryaev. 1995. Optimization of the flow of dividends. Russian Math. Surveys 50: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubalek, Friedrich, and Walter Schachermayer. 2004. Optimizing expected utility of dividend payments for a Brownian risk process and a peculiar nonlinear ODE. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 34: 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffen, Ronnie L. 2008. On optimality of the barrier strategy in de Finetti’s dividend problem for spectrally negative Lévy processes. The Annals of Applied Probability 18: 1669–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noba, Kei. 2021. On the optimality of double barrier strategies for Lévy processes. Stochastic Processes and their Applications 131: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, Vojislav. 1972. Asymptotic behavior of solutions of nonlinear differential equation of the first order. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 38: 187–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, Jostein. 2007. Optimal dividend payments until ruin of diffusion processes when payments are subject to both fixed and proportional costs. Advances in Applied Probability 39: 669–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidli, Hanspeter. 2008. Stochastic Control in Insurance. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thonhauser, Stefan, and Hansjörg Albrecher. 2011. Optimal dividend strategies for a compound Poisson risk process under transaction costs and power utility. Stochastic Models 27: 120–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Xiaowen. 2005. On a classical risk model with a constant dividend barrier. North American Actuarial Journal 9: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| x | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.8021 | 1.9000 | 0.2770 |

| 1 | 8.5790 | 1.6929 | 0.3489 |

| 2 | 10.2022 | 1.5575 | 0.4122 |

| 3 | 11.7010 | 1.4431 | 0.4802 |

| 4 | 13.0940 | 1.3454 | 0.5525 |

| 5 | 14.3963 | 1.2613 | 0.6286 |

| 6 | 15.6203 | 1.1884 | 0.7081 |

| 7 | 16.7762 | 1.1247 | 0.7905 |

| 8 | 17.8723 | 1.0687 | 0.8755 |

| 9 | 18.9158 | 1.0192 | 0.9626 |

| 10 | 19.9126 | 0.9752 | 1.0515 |

| x | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.8000 | 2.0000 | 0.2500 |

| 1 | 9.4022 | 3.1941 | 0.0980 |

| 2 | 13.3275 | 4.7502 | 0.0443 |

| 3 | 19.1343 | 7.0039 | 0.0204 |

| 4 | 27.6771 | 10.2878 | 0.0094 |

| 5 | 40.2103 | 15.0801 | 0.0044 |

| 6 | 58.5692 | 22.0787 | 0.0021 |

| 7 | 85.4378 | 32.3029 | 0.0010 |

| 8 | 124.7394 | 47.2425 | 0.0004 |

| 9 | 182.2094 | 69.0750 | 0.0002 |

| 10 | 266.2320 | 100.9833 | 0.0001 |

| b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correctness | Value | a | A | |

| t.b. | ≥1.97 | - | - | - |

| c. | 1.96 | 6.798693877 | 6.783185889 | 0.015507988 |

| c. | 1.95 | 6.798803418 | 6.784849201 | 0.013954217 |

| c. | 1.94 | 6.799092783 | 6.786580941 | 0.012511842 |

| c. | 1.93 | 6.799564767 | 6.788388955 | 0.011175812 |

| c. | 1.92 | 6.800222221 | 6.790283409 | 0.009938812 |

| c. | 1.91 | 6.801068062 | 6.792277924 | 0.008790138 |

| c. | 1.90 | 6.802105263 | 6.794392618 | 0.007712645 |

| c. | 1.89 | 6.803336861 | 6.796662198 | 0.006674663 |

| t.s. | 1.88 | - | - | - |

| t.s. | 1.881 | - | - | - |

| c. | 1.882 | 6.804464186 | 6.798652236 | 0.005811950 |

| c. | 1.8819 | 6.804479085 | 6.798679195 | 0.005799890 |

| t.s. | 1.8818 | - | - | - |

| t.s. | ⋮ | - | - | - |

| t.s. | 1.88185 | - | - | - |

| c. | 1.88186 | 6.804485051 | 6.798690050 | 0.005795001 |

| c. | 1.881859 | 6.804485199 | 6.798690322 | 0.005794877 |

| c. | 1.881858 | 6.804485348 | 6.798690594 | 0.005794754 |

| c. | 1.881857 | 6.804485498 | 6.798690867 | 0.005794631 |

| c. | 1.881856 | 6.804485647 | 6.798691139 | 0.005794508 |

| c. | 1.881855 | 6.804485795 | 6.798691412 | 0.005794383 |

| c. | 1.881854 | 6.804485945 | 6.798691685 | 0.005794260 |

| c. | 1.881853 | 6.804486095 | 6.798691958 | 0.005794137 |

| c. | 1.881852 | 6.804486243 | 6.798692231 | 0.005794012 |

| c. | 1.881851 | 6.804486392 | 6.798692504 | 0.005793888 |

| t.s. | 1.881850 | - | - | - |

| t.s. | ⋮ | - | - | - |

| t.s. | 1.8818503 | - | - | - |

| c. | 1.8818504 | 6.804486482 | 6.798692667 | 0.005793815 |

| c. | 1.88185039 | 6.804486484 | 6.798692671 | 0.005793813 |

| c. | 1.88185038 | 6.804486485 | 6.798692673 | 0.005793812 |

| c. | 1.88185037 | 6.804486486 | 6.798692675 | 0.005793811 |

| c. | 1.88185036 | 6.804486488 | 6.798692679 | 0.005793809 |

| c. | 1.88185035 | 6.804486489 | 6.798692681 | 0.005793808 |

| t.s. | 1.88185034 | - | - | - |

| t.s. | 1.881850341 | - | - | - |

| c. | 1.881850342 | 6.804486491 | 6.798692684 | 0.005793807 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baran, S.; Constantinescu, C.; Palmowski, Z. Asymptotic Expected Utility of Dividend Payments in a Classical Collective Risk Process. Risks 2023, 11, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11040064

Baran S, Constantinescu C, Palmowski Z. Asymptotic Expected Utility of Dividend Payments in a Classical Collective Risk Process. Risks. 2023; 11(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaran, Sebastian, Corina Constantinescu, and Zbigniew Palmowski. 2023. "Asymptotic Expected Utility of Dividend Payments in a Classical Collective Risk Process" Risks 11, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11040064

APA StyleBaran, S., Constantinescu, C., & Palmowski, Z. (2023). Asymptotic Expected Utility of Dividend Payments in a Classical Collective Risk Process. Risks, 11(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11040064