Subjective Experiences of At-Risk Children Living in a Foster-Care Village Who Participated in an Open Studio

Abstract

:1. Children at Risk in Foster Care

2. Childhood Trauma

3. The Visual Art Medium as a Therapeutic Tool for Treating Children at Risk

4. The Open Studio Model

5. Method

5.1. The Research Approach

5.2. Participants

5.3. Research Tools

5.4. Procedure

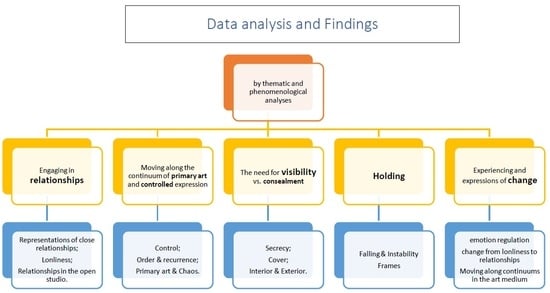

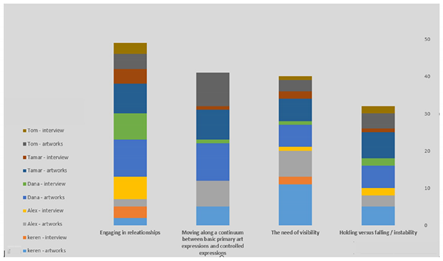

6. Data Analysis

7. Findings

7.1. Engaging in Relationships

7.2. Close Relationships

7.3. Loneliness

7.4. Relationships in the Open Studio

8. Control

8.1. Characteristics of Order and Recurrence

8.2. Primary Art Expressions (e.g., Smearing, Scribbling, etc.) and Expressions of Chaos

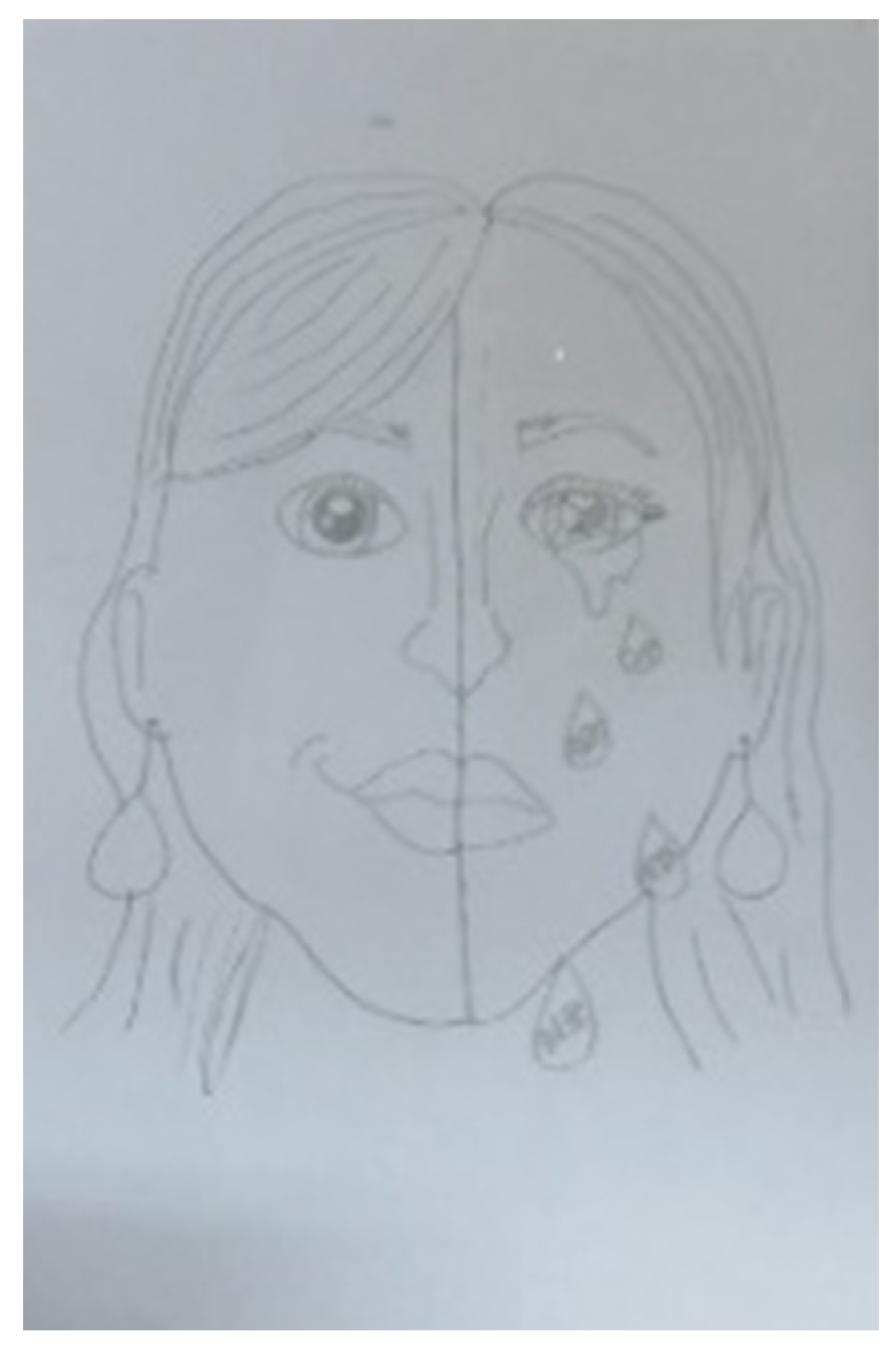

8.3. Visibility—Concealment and Discernibility

8.4. Secrecy

8.5. Cover

8.6. Interior and Exterior

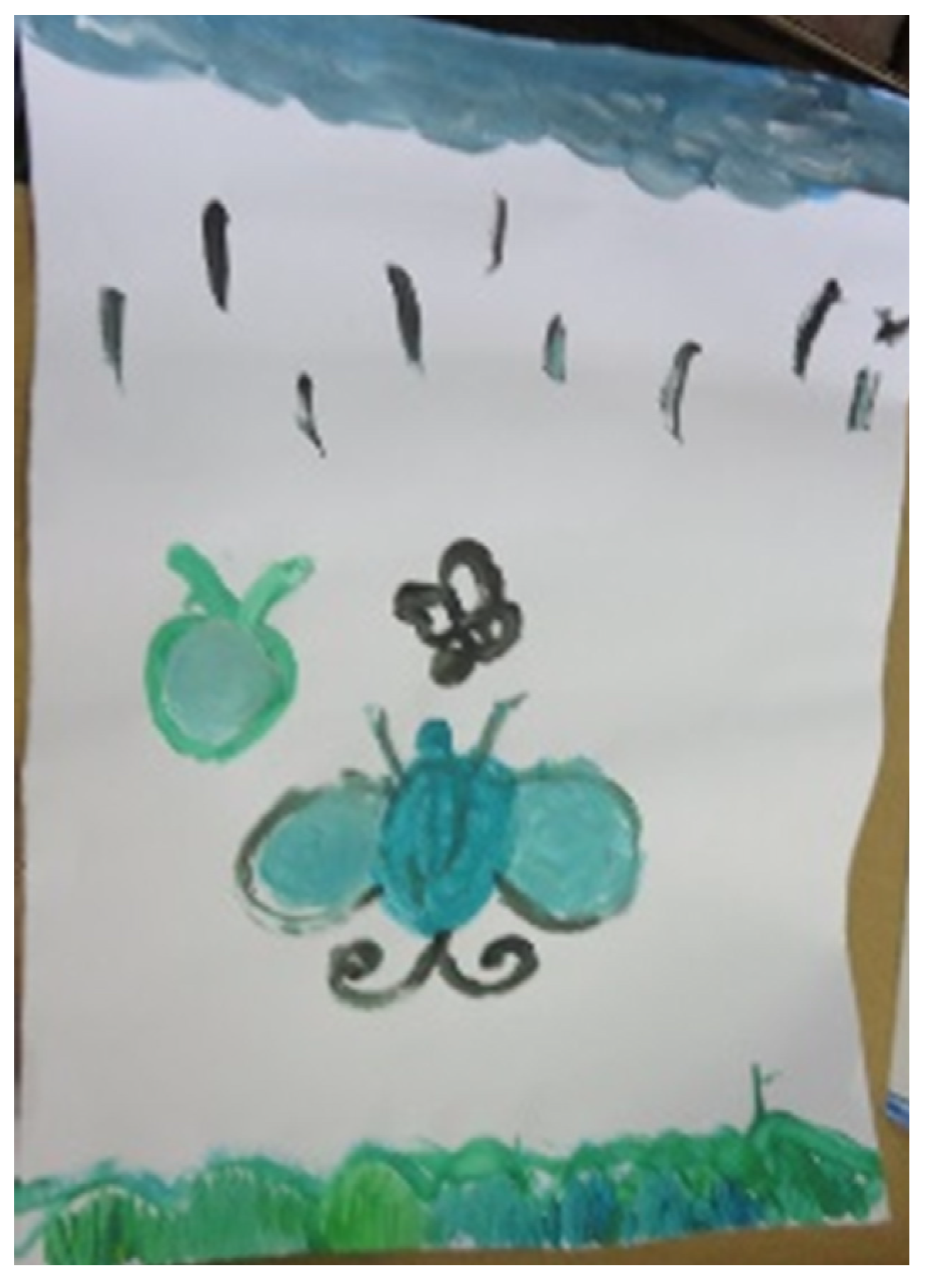

8.7. Holding versus Falling/Instability

8.7.1. Holding

8.7.2. Falling and Instability

8.8. Experiencing Change and Expressions of Change

9. Discussion

9.1. Nonverbal Expressions of Trauma and Loss in the Open Studio

9.2. The Formation of an Alternative Envelope in Which the Need to Be Held, to Be Seen, and Move between Opposite Poles Is Expressed

9.3. Experiences of Change in the Open Studio

9.4. Limitations of This Study and Recommendations for Future Research

9.5. Practical Implications for the Research and Clinical Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Camilleri, V.A. Healing the Inner-City Child: Creative Arts Therapies with At-Risk Youth; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zilberstein, K. Neurocognitive considerations in the treatment of attachment and complex trauma in children. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz, H. Tackling child neglect: A role for pediatricians. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 56, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council for the Child. NCC Statistical Yearbook: Children in Israel; National Council for the Child: Jerusalem, Israel, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.; White, J.; Turley, R.; Slater, T.; Morgan, H.; Strange, H.; Scourfield, J. Comparison of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide in children and young people in care and non-care populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, D.; Tzioumi, D. Health needs of Australian children living in out-of-home care. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2007, 43, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Comtois, K.; Cyr, C.; Pennestri, M.H.; Godbout, R. Poor quality of sleep in foster children relates to maltreatment and placement conditions. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 2158244016669551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javakhishvili, M.; Widom, C.S. Out-of-home placement, sleep problems, and later mental health and crime: A prospective investigation. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2022, 92, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruskas, D. Children in foster care: A vulnerable population at risk. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2008, 21, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houzel, D. The family envelope and what happens when it is torn. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1996, 77, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.G.; Fonagy, P. Trauma. In Handbook of Psychodynamic Approaches to Psychopathology; Luyten, P., Mayes, L.C., Fonagy, P., Target, M., Blatt, S.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 165–198. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C. Expressive Arts Therapy for Traumatized Children and Adolescents: A Four-Phase Model; Routledge Publication: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, W.; Raider, M. Structured Sensory Intervention for Traumatiazed Children, Adolescents and Parents (SITCAP), 3rd ed.; Edwin Mellen Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hass-Cohen, N.; Findlay; Clyde, J.; Carr, R.; Vanderlan, J. Check, change what you need to change and/or keep what you want: An art therapy neurobiological-based trauma protocol. Am. J. Art Ther. 2014, 31, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. In Healing Trauma: Attachment, Mind, Body and Brain; Solomon, M., Siegel, D., Eds.; W.W.Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 168–195. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, D.A. Neuroscience and trauma treatment: Implications for creative arts therapists. In Expressive and Creative Arts Methods for Trauma Survivors; Carey, L., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2006; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, K.J.; Kindsvatter, A.; Stahl, S.; Smith, H. Using Creative Techniques With Children Who Have Experienced Trauma. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2015, 10, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moula, Z.; Powell, J.; Karkou, V. Qualitative and Arts-Based Evidence from Children Participating in a Pilot Randomised Controlled Study of School-Based Arts Therapies. Children 2022, 9, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Westrhenen, N.; Fritz, E. Creative arts therapy as treatment for child trauma: An overview. Art Psychother. 2014, 41, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coholic, D.; Lougheed, S.; Cadell, S. Exploring the helpfulness of arts-based methods with children living in foster care. Traumatology 2009, 15, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coholic, D.; Lougheed, S.; LeBreton, J. The helpfulness of holistic arts-based group work with children living in foster care. Soc. Work Groups 2009, 32, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSunno, R.; Linton, K.; Bowes, E. World trade center tragedy: Concomitant healing in traumatic grief through art therapy with children. Traumatology 2011, 17, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, L.; Lettenberger, C.; Nedela, M.; Soloski, K.L. The body tells the story: Using art to facilitate children’s narratives. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2010, 5, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluations and guidelines for future work. Child. Dev. 2000, 16, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worrall, J.; Jerry, P. Resiliency and its relationship to art therapy. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 2007, 20, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, W. Drawing: An evidence-based intervention for trauma victims. RCY 2009, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, E. Art as Therapy; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, D.; Bat Or, M. The Open Studio Approach to Art Therapy: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, P.B. Coyote comes in from the cold: The evolution of the open studio concept. Am. J. Art Ther. 1995, 12, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. Commentary on community based art studios: Underlying principles. Am. J. Art Ther. 2008, 25, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, A. The Contribution of “Open Studio” Program. based Experiential-Learning to Developing Reflection Abilities and Self Efficacy of Elementary-School Children. Dissertation, Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J. Open studio: Model for art therapy based on spontaneous creation process from an open, non-directing therapeutic approach. In Creation–The Heart of Therapy; Berger, R., Ed.; Ach Publications: Kiryat Bialik, Israel, 2014; pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Block, D.; Harris, T.; Laing, S. Open studio process as a model of social action: A program for at-risk youth. Am. J. Art Ther. 2005, 22, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Ray, K. Free art-making in an art therapy open studio: Changes in affect and self-efficacy. Arts Health 2016, 9, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor Inbar, N. Draw Your Story: The Main Themes That Arise from the Art Works of Adolescent Girls at Risk in an Open Studio in a Boarding School; Thesis in the School of Creative Arts Therapies; University of Haifa: Haifa, Israel, 2020. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Czamanski-Cohen, J. “Oh! Now I remember”: The use of a studio approach to art therapy with internally displaced people. Art Psychother. 2010, 37, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitan, L. Introduction to Art Therapy Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications: California, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gavron, T.; Sholt, M.; Sela, A. Observation Rating Scales Sheet for Art Therapy Practice; School of Creative Arts Therapy, University of Haifa: Haifa, Israel, 2009/2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lusebrink, V.B. Imagery and Visual Expression in Therapy; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kagin, S.L.; Lusebrink, V.B. The Expressive Therapies Continuum. Art Psychother. 1978, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusebrink, V.B.; Martinsone, K.; Silova, I.D. The Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC): Interdisciplinary bases of the ETC. Int. J. Art Ther. 2013, 18, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantt, L.; Tabone, C. The Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale: A Rating Manual; Plenum Press: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, T.H. The Primitive Edge of Experience; Jason Aronson: Northvale, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, L. Between Stars and Sand: Art Therapy and Sandplay Tharapy; Seagat Press: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2004. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, T.H. On holding and containing, being and dreaming. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2004, 85, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnicott, D.W. The depressive position in normal emotional development. In Through Paediatrics to Psychoanalysis; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1954/1975; pp. 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. Primary maternal preoccupation. In The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment; International University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1956/1965; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell-Kirk, R. Secrets, symbols, synthesis, and safety: The role of boxes in art therapy. Am. J. Art Ther. 2001, 39, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, C.; Ford, J. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schore, A.N.; Schore, J.R. Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2009, 36, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantt, L.; Tripp, T. The Image Comes First: Treating Preverbal Trauma with Art Therapy. In Art Therapy, Trauma, and Neuroscience: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives; King, J.L., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.E.; Whiting, J.B. Foster children’s expressions of ambiguous loss. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2007, 35, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.B. “No one acknowledged my loss and hurt”: Non-death loss, grief, and trauma in foster care. Child. Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2017, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, S.; Malkinson, R.; Witztum, E. Introduction to the theory and clinical applications of the two-track model of bereavement. In Working with the Bereaved: Multiple Lenses on Loss and Mourning; Rubin, S., Malkinson, R., Witztum, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H.A.W. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rational and description. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M.S.; Hansson, R.O.; Stroebe, W.; Schut, H. Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bat Or, M.; Garti, D. Art therapists’ perceptions of the art medium’s roles in the treatment of the bereaved. Death Stud. 2018, 43, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klorer, P.G. Neuroscience and art therapy with severely traumatized children: The art is the evidence. In Art Therapy, Trauma, and Neuroscience: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives; King, J.L., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, R. Working with the Developmental Trauma of Childhood Neglect: Using Psychotherapy and Attachment Theory Techniques in Clinical Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.T.; Cassidy, J. Expressive suppression of negative emotions in children and adolescents: Theory, data, and guide for future research. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 1938–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dich, N.; Doan, S.N.; Evans, G.W. In risky environments, emotional children have more behavioral problems but lower allostatic load. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, J. Seeing and Being Seen: Emerging from a Psychic Retreat; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sela, T.; Bat Or, M. “You Have Your Eyesight and You Do Not See:” Representations of sight and blindness as manifested in the artistic and verbal expressions of adults who grew up in the shadow of a secret. Art Psychother. 2022, 80, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbrecht, C. Trauma and Healing at the Clay Field: A Sensorimotor Art Therapy Approach; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G.; Ray, K.; Muniz, J. Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants’ Responses Following Art Making. Am. J. Art Ther. 2016, 33, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, S.; Yilmaz, M.; Çvdar, A. Mentalization, session-by-session negative emotion expression, symbolic play, and affect regulation in psychodynamic child psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 2019, 56, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusebrink, V.B.; Hinz, L. The Expressive Therapies Continuum as a framework in the treatment of trauma. In Art Therapy, Trauma, and Neuroscience: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives; King, J.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 42–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, L.D. Expressive Therapies Continuum; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bat Or, M. Art therapy with AD/HD children: Exploring possible selves via art. In Innovative Practice and Interventions for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Difficulties, Disorders, and Disabilities; Kourkoutas, E.E., Hart, A., Mouzaki, A., Eds.; Cambridge Scholar Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015; pp. 373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, K.; Backos, A.; Malchiodi, C.; Spiegel, D. Art therapy for combat-related PTSD: Reccomendations for research and practice. Am. J. Art Ther. 2006, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, E.; Mancinas, S.; Skoog, V. We are not orphans. Children’s experience of everyday life in institutional care in Mexico. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Number of Studio Sessions Attended | Number of Artworks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dana | 10 | Girl | 42 | 47 |

| Tom | 9 | Boy | 21 | 21 |

| Keren | 8 | Girl | 31 | 44 |

| Tamar | 7 | Girl | 41 | 109 |

| Alex | 8 | Girl | 21 | 44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bat Or, M.; Zusman-Bloch, R. Subjective Experiences of At-Risk Children Living in a Foster-Care Village Who Participated in an Open Studio. Children 2022, 9, 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081218

Bat Or M, Zusman-Bloch R. Subjective Experiences of At-Risk Children Living in a Foster-Care Village Who Participated in an Open Studio. Children. 2022; 9(8):1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081218

Chicago/Turabian StyleBat Or, Michal, and Reut Zusman-Bloch. 2022. "Subjective Experiences of At-Risk Children Living in a Foster-Care Village Who Participated in an Open Studio" Children 9, no. 8: 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081218

APA StyleBat Or, M., & Zusman-Bloch, R. (2022). Subjective Experiences of At-Risk Children Living in a Foster-Care Village Who Participated in an Open Studio. Children, 9(8), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081218