Does Self-Control Promote Prosocial Behavior? Evidence from a Longitudinal Tracking Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

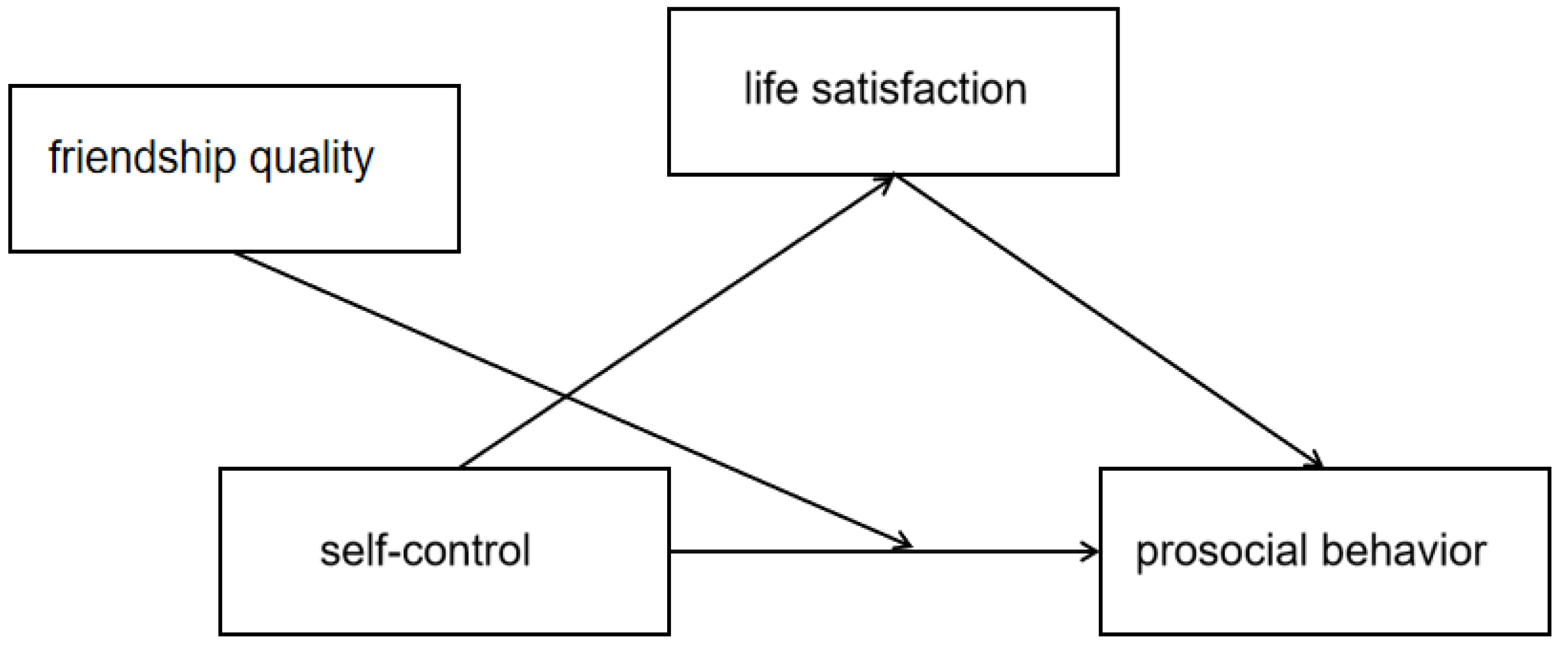

1.1. Self-Control and Prosocial Behavior

1.2. Life Satisfaction as a Potential Mediator

1.3. Friendship Quality as a Potential Moderator

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Brief Self-Control Questionnaire

2.4. Prosocial Behavior Scale

2.5. Friendship Quality Scale

2.6. Life Satisfaction Scale

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

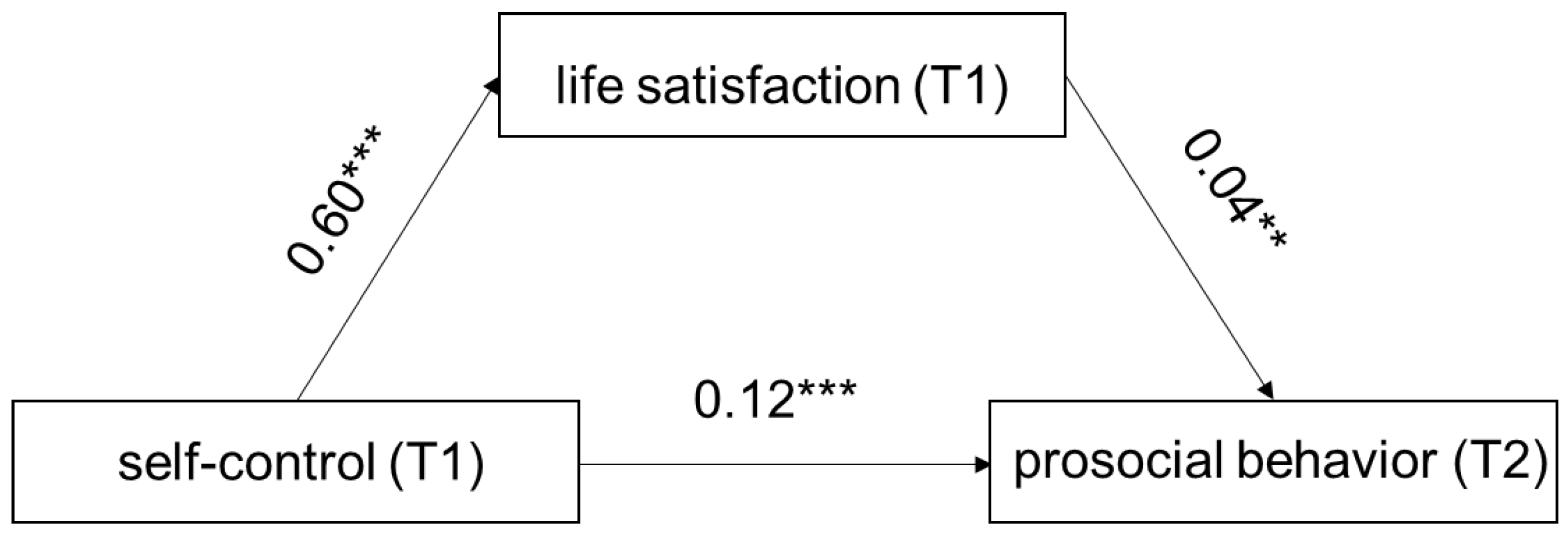

3.3. Mediation Testing

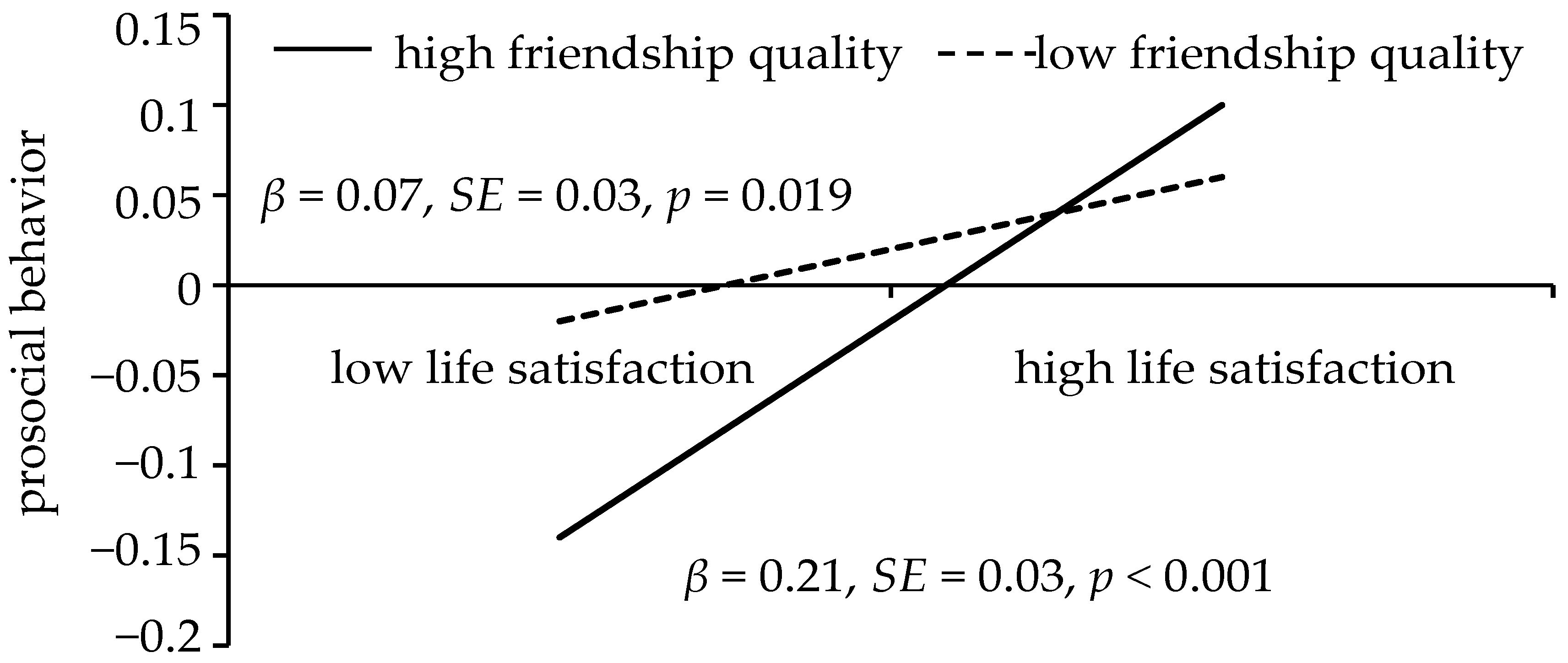

3.4. Mediation-Moderated Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schoeps, K.; Mónaco Gerónimo, E.; Cotolí, A.; Montoya-Castilla, I. The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.; Yang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Ma, J. When Do Good Deeds Lead to Good Feelings? Eudaimonic Orientation Moderates the Happiness Benefits of Prosocial Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yao, M.; Liu, H. From Social Support to Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation and Prosocial Behavior and Gender Difference. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, A.; Siddiqui, D. Effect of Religiosity and Spirituality on Employees Prosocial Behavior with the Mediatory Role of Humanism and Ethics. Int. J. Soc. Work. 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí Vilar, M.; Merino, C.; Rodriguez, L. Measurement Invariance of the Prosocial Behavior Scale in Three Hispanic Countries (Argentina, Spain, and Peru). Front. Psychol 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Guo, Y.J.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C. Chinese adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment: The contribution of mothers’ attachment style and adolescents’ attachment to mother. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 2597–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Willenbrink, J.; Bliske, M.; Brinckman, B. Emotion Sharing in Preadolescent Children: Divergence From Friendships and Relation to Prosocial Behavior in the Peer Group. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 42, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huanhuan, Z. Influence of urban residents’ life satisfaction on prosocial behavioral intentions in the community: A multiple mediation model. J. Community 2020, 49, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallings, M.C.; Hewitt, J.K. Conceptualization and measurement of organism-environment interaction. Behav. Genet. 1994, 24, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, A.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Zhan, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhong, Y. The Effect of Preceding Self-Control on Prosocial Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Awe. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Barad, T.; Uziel, L. When (state and trait) powers collide: Effects of power-incongruence and self-control on prosocial behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 162, 110009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisi, M. Pandora’s box: The consequences of low self-control into adulthood. In Handbook of Life-Course Criminology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Vazsonyi, A.T.; Mikuška, J.; Kelley, E.L. It’s time: A meta-analysis on the self-control-deviance link. J. Crim. Justice 2017, 48, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, H.D.; Yamini, S. Parenting practices, self-control and anti-social behaviors: Meta-analytic structural equation modeling. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 68, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 271–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H. Self-Control Modulates the Behavioral Response of Interpersonal Forgiveness. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, J.; Muraven, M. Self-Control Depletion Does Not Diminish Attitudes About Being Prosocial But Does Diminish Prosocial Behaviors. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, T.; Krampe, H. Meaning in Life and Self-Control Buffer Stress in Times of COVID-19: Moderating and Mediating Effects With Regard to Mental Distress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, P.; Llorca, A.; Malonda, E.; Mestre, V. Examining the predictors of prosocial behavior in young offenders and nonoffenders. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2021, 45, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Hein, G.; Hewig, J. Between Joy and Sympathy: Smiling and Sad Recipient Faces Increase Prosocial Behavior in the Dictator Game. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6172. [Google Scholar]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, A.; van Dijke, M.; Van Hiel, A.; De Cremer, D. Out of control!? How loss of self-control influences prosocial behavior: The role of power and moral values. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126377. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmelík, F.; Frömel, K.; Groffik, D.; Šafář, M.; Mitáš, J. Does Vigorous Physical Activity Contribute to Adolescent Life Satisfaction? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.; Sotardi, V.; Park, J.; Roy, D. Gender self-confidence, scholastic stress, life satisfaction, and perceived academic achievement for adolescent New Zealanders. J. Adolesc. 2021, 88, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, K.; Li, J.B.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, J.J.; Liang, Z.Q.; Nie, Y.G. Engaging in prosocial behavior explains how high self-control relates to more life satisfaction: Evidence from three Chinese samples. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223169. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, K.; Nie, Y.-G.; Wang, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-Z. The relationship between self-control, job satisfaction and life satisfaction in Chinese employees: A preliminary study. Work 2016, 55, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B.; Delvecchio, E.; Lis, A.; Nie, Y.-G.; Di Riso, D. Positive coping as mediator between self-control and life satisfaction: Evidence from two Chinese samples. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 97, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zainun, N.F.; Johanim, J.; Adnan, Z. Machiavellianism, locus of control, moral identity, and ethical leadership among public service leaders in Malaysia: The moderating effect of ethical role modelling. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 41, 1108–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiang, G.; Song, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, H. Examining the Associations of Trait Self-control with Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 23, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, C.; Skagerlund, K.; Västfjäll, D.; Tinghög, G. Subjective self-control but not objective measures of executive functions predicts financial behavior and well-being. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 27, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.T.; Gillebaart, M.; Kroese, F.; De Ridder, D. Why are people with high self-control happier? The effect of trait self-control on happiness as mediated by regulatory focus. Front. Psychol 2014, 5, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, W.; Luhmann, M.; Fisher, R.R.; Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. J. Pers. 2014, 82, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gombert, L.; Rivkin, W.; Schmidt, K.H. Indirect Effects of Daily Self-Control Demands on Subjective Vitality via Ego Depletion: How Daily Psychological Detachment Pays Off. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 69, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massar, K.; Bělostíková, P.; Sui, X. It’s the thought that counts: Trait self-control is positively associated with well-being and coping via thought control ability. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 2372–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Tian, L.; Huebner, E.S. The reciprocal relations among prosocial behavior, satisfaction of relatedness needs at school, and subjective well-being in school: A three-wave cross-lagged study among Chinese elementary school students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3734–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Papies, E.K.; Preston, S.D.; Sauter, D.A. Positive affect and behavior change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 39, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, O.; Liu, L.; Zha, Y. Awe and prosocial tendency. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Upenieks, L. Moral Self-Appraisals Explain Emotional Rewards of Prosocial Behavior. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.B.; Larson, J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hamburg, Germany; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Hoza, B. Popularity and friendship: Issues in theory, measurement, and outcome. In Peer Relationships in Child Development; Berndt, T.J., Ladd, G.W., Eds.; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.G.; Asher, S.R. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.J. Relations Between Teacher Interpersonal Communication Styles and Student Prosocial-and-Antisocial Behaviors in Physical Education Context. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 56, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Elksnin, L.K.; Elksnin, N. Teaching Parents to Teach Their Children to Be Prosocial. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2000, 36, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, T.J.; Kelly, B. Children making “fun”: Humorous communication, impression management, and moral development. Child Study J. 1994, 24, 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo, G.; Crockett, L.J.; Wolff, J.M.; Beal, S.J. The role of emotional reactivity, self-regulation, and puberty in adolescents’ prosocial behaviors. Soc. Dev. 2012, 21, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barry, C.M.; Wentzel, K.R. Friend influence on prosocial behavior: The role of motivational factors and friendship characteristics. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, M.; Lecce, S.; Pagnin, A.; Banerjee, R. Longitudinal effects of theory of mind on later peer relations: The role of prosocial behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, R.; Watling, D.; Caputi, M. Peer relations and the understanding of faux pas: Longitudinal evidence for bidirectional associations. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1887–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinrad, T.L.; Eisenberg, N.; Cumberland, A.; Fabes, R.A.; Valiente, C.; Shepard, S.A. Relation of emotion- related regulation to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion 2006, 6, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, Z.E.; Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D.; Sulik, M.J. The relations of ego-resiliency and emotion socialization to the development of empathy and prosocial behavior across early childhood. Emotion 2013, 13, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batson, C.D. Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 20, 65–122. [Google Scholar]

- Boman, J.H.; Krohn, M.D.; Gibson, C.L.; Stogner, J.M. Investigating Friendship Quality: An Exploration of Self-Control and Social Control Theories’ Friendship Hypotheses. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Padilla-Walker, L. Happy Helpers: A Multidimensional and Mixed-Method Approach to Prosocial Behavior and Its Effects on Friendship Quality, Mental Health, and Well-Being During Adolescence. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1705–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, M.R.; Hirschi, T. A General Theory of Crime; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Methodology in the Social Sciences, Kindle ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 1, p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well–being: Three decades of progress. Psychol.-Ical Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A.; Yaari, S. Parental Flow and Positive Emotions: Optimal Experiences in Parent–Child Interactions and Parents’ Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 23, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Berg, J.M.; Zlatev, J.J. Emotional acknowledgment: How verbalizing others’ emotions fosters interpersonal trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2021, 164, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Chen, W.-L.; Tsai, L.-T.; Wu, M.-S.; Hong, C.-L. Interpersonal Mechanisms in the Relationships between Dependency/Self-Criticism and Depressive Symptoms in Taiwanese Undergraduates: A Prospective Study. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 31, 972–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.Y.; DeSteno, D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.K.; Tunney, R.J.; Ferguson, E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 601–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, J.-A.; Martin, S.R. Four experiments on the relational dynamics and prosocial consequences of gratitude. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 14, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Kimeldorf, M.B.; Cohen, A.D. An adaptation for altruism: The social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 17, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickens, L.; DeSteno, D. The grateful are patient: Heightened daily gratitude is associated with attenuated temporal discounting. Emotion 2016, 16, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSteno, D.; Li, Y.; Dickens, L.; Lerner, J.S. Gratitude: A tool for reducing economic impatience. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-control | ||||

| 2. Life Satisfaction | 0.31 *** | |||

| 3. Prosocial Behavior | 0.21 *** | 0.16 *** | ||

| 4. Friendship Quality | 0.18 *** | −0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Mean | 3.13 | 4.26 | 2.44 | 2.87 |

| SD | 0.56 | 1.28 | 0.41 | 0.84 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, W.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, D. Does Self-Control Promote Prosocial Behavior? Evidence from a Longitudinal Tracking Study. Children 2022, 9, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060854

Li J, Chen Y, Lu J, Li W, Zhen S, Zhang D. Does Self-Control Promote Prosocial Behavior? Evidence from a Longitudinal Tracking Study. Children. 2022; 9(6):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060854

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jingjing, Yanhan Chen, Jiachen Lu, Weidong Li, Shuangju Zhen, and Dan Zhang. 2022. "Does Self-Control Promote Prosocial Behavior? Evidence from a Longitudinal Tracking Study" Children 9, no. 6: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060854

APA StyleLi, J., Chen, Y., Lu, J., Li, W., Zhen, S., & Zhang, D. (2022). Does Self-Control Promote Prosocial Behavior? Evidence from a Longitudinal Tracking Study. Children, 9(6), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060854