Epidemiology and Surgical Management of Foreign Bodies in the Liver in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

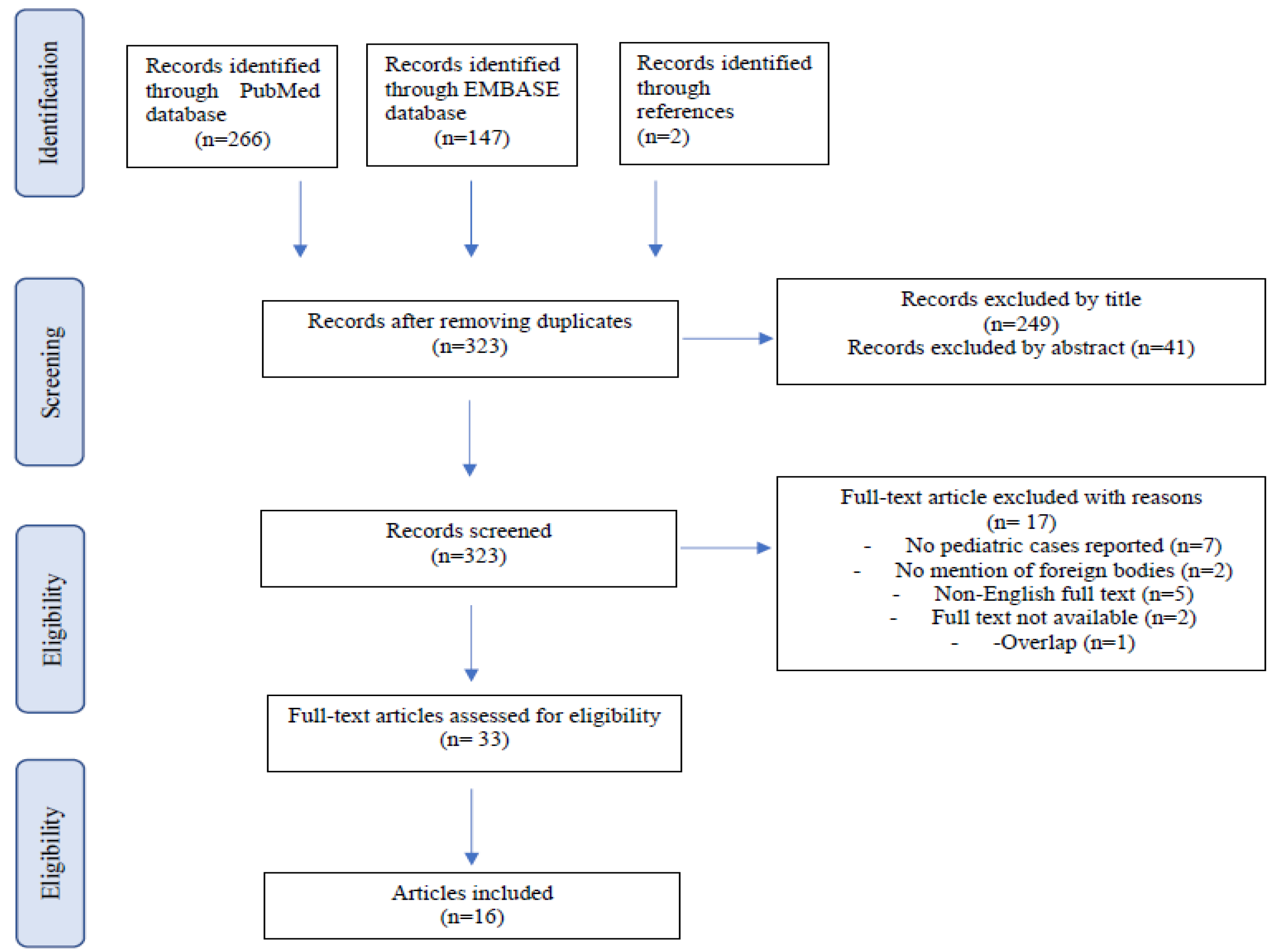

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crankson, S.J. Hepatic Foreign Body in a Child. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 1997, 12, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.; Wildhaber, B.E.; Spadola, L.; Mehrak, A.D.; Chardot, C. Laparoscopic Extraction of an Intrahepatic Foreign Body after Transduodenal Migration in a Child. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 44, e17–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.-W.; Shen, M.-D.; Shi, S.-H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, S.-S. Foreign Body Retained in Liver Long after Gauze Packing. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3364–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thipphavong, S.; Kellenberger, C.J.; Rutka, J.T.; Manson, D.E. Hepatic and Colonic Perforation by an Abandoned Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt. Pediatr. Radiol. 2004, 34, 750–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.D.; Baker, D.; Takhar, A.; Beattie, R.M.; Stanton, M.P. Complication of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, W.A.; Simo, K.A.; Swan, R.Z.; Sindram, D.; Iannitti, D.A.; Martinie, J.B. Pyogenic Hepatic Abscess Secondary to Endolumenal Perforation of an Ingested Foreign Body. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012, 16, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geramizadeh, B.; Jahangiri, R.; Moradi, E. Causes of Hepatic Granuloma: A 12-Year Single Center Experience from Southern Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2011, 14, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.A. Hepatic Abscess Induced by Foreign Body: Case Report and Literature Review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1466–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giestas, S.; Mendes, S.; Gomes, D.; Sofia, C. Obstructive Jaundice Due to Foreign Body in the Bile Duct: An Unusual Finding. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 23, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, B.; Jones, D.; Sarrazin, J.; Coburn, N.G. Porta Hepatis Abscess and Portal Vein Thrombosis Following Ingestion of a Fishbone. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e227271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, S.; Matsuo, S.; Hidaka, M.; Azuma, T.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kanematsu, T. Impaction of a Shrapnel Splinter in the Common Bile Duct After Migrating from the Right Thoracic Cavity: Report of a Case. Surg. Today 2002, 32, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetc, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool to Assess the Quality of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto, Y.; Suita, S.; Taguchi, T.; Noguchi, S.I.; Ieiri, S. Hepatic Foreign Body-A Sewing Needle-In a Child. Asian J. Surg. 2003, 26, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Azili, M.N.; Karaman, A.; Karaman, I.; Erdoǧan, D.; Çavuşoǧlu, Y.H.; Aslan, M.K.; Çakmak, Ö. A Sewing Needle Migrating into the Liver in a Child: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2007, 23, 1135–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcu, S.; Ünal, Ö.; Özen, Ö.; Bora, A.; Dülger, A.C. A Swallowed Sewing Needle Migrating to the Liver. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 1, 193–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bakal, U.; Tartar, T.; Kazez, A. A Rare Mode of Entry for Needles Observed in the Abdomen of Children: Penetration. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2012, 17, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.-J.; Lü, C.-J.; Liu, W.-G.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, Y.-B. A Sewing Needle Within the Right Hepatic Lobe of an Infant. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2013, 29, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Ilıkan, G.B.; Ertürk, A.; Şahin, V.S.; Öztorun, C.İ.; Güney, D.; Erten, E.E.; Azılı, M.N.; Şenel, E. Removal of Two Needles from the Liver and Axillary Region Using Ultrasound: A Case Report with Current Literature Review. Med. Bull. Haseki 2020, 58, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitua, F.; Acosta, S.; Soto, G.; Herrera, P.; Tapia, D. To Remove or Not RemoveIAsymptomatic Sewing Needle Within Hepatic Right Lobe in an Infant. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2009, 25, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marya, K.M.; Yadav, V.; Rattan, K.N.; Kundu, Z.S.; Sangwan, S.S. Unusual K-Wire Migration. Indian J. Pediatr. 2006, 73, 1107–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyak, J.M.; Todd, H.; Rubalcava, D.; Vogel, A.M.; Fallon, S.; Naik-Mathuria, B. Barely Benign: The Dangers of BB and Other Nonpowder Guns. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, T.; Nwomeh, B.; Abdessalam, S.; Groner, J. Paradoxical Missile Embolus to the Right Superficial Femoral Artery Following Gunshot Wound to the Liver: A Case Report. J. Trauma-Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2004, 57, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçam, M.; Koçkar, C.; Tola, H.T.; Duman, L.; Gündüz, M. Endoscopic Removal of an Ingested Pin Migrated into the Liver and Affixed by Its Head to the Duodenum. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009, 69, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyuca, S.; Doǧan, M.; Kaya, A.; Ay, M. An Unusual Cause of Liver Abscess. Liver Int. 2009, 29, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Mandat-Schultz, A.; Arnaud, B.; Nadia, B.; Aigrain, Y.; de Lagausie, P. Intrahepatic Foreign Body Laparoscopic Extraction. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 1849. [Google Scholar]

- Fragulidis, G.P.; Chondrogiannis, K.D.; Karakatsanis, A.; Lykoudis, P.M.; Melemeni, A.; Polydorou, A.; Voros, D. Cystoid Gossypiboma of the Liver 15 Years after Cholecystectomy. Am. Surg. 2011, 77, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, A.; Morris, J.; Goddard, C.; Mahmud, S.; Nassar, A.H.M. Delayed Cholangitis Resulting from a Retained T-Tube Fragment Encased within a Stone. Surg. Endosc. 2002, 16, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ikeda, E.; Mitsunaga, S.; Naitoh, M.; Nawa, S.; Furutani, S. Choledochal Stenosis and Lithiasis Caused by Penetration and Migration of Surgical Metal Clips. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2000, 7, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumura, H.; Ichikawa, T.; Kagawa, T.; Nishihara, M.; Yoshikawa, K.; Yamamoto, G. Failure of Endoscopic Removal of Common Bile Duct Stones Due to Endo-Clip Migration Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2002, 9, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimsit, B.; Keskin, M.; Ozden, I.; Alper, A. Obstructive Jaundice Due to a Textiloma Mimicking a Common Bile Duct Stone. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2006, 13, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, V.; Lubhana, P.; Durkhere, R.; Bhandari, S. Liver Abscess Secondary to a Broken Needle Migration—A Case Report. BMC Surg. 2003, 3, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, R.M.; Fischer, J.E.; Hendren, W.H. Penetration of the Alimentary Tract by a Foreign Body with Migration to the Liver Report of a Case. Arch. Surg. 1971, 102, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senol, A.; Işler, M.; Minkar, T.; Oyar, O. A Sewing Needle in the Liver: 6 Years Later. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 339, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Zhuo, J.; Wen, X.; Ling, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, H.; Xu, X.; Zheng, S. Laparoscopic Management of Enterohepatic Migrated Fish Bone Mimicking Liver Neoplasm. Medicine 2019, 98, e14705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, M.; Prasad, J.; Schaewe, H.; Donoghue, L.; Langenburg, S. Nonpowder Firearms Cause Significant Pediatric Injuries. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 78, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güsgen, C.; Willms, A.; Richardsen, I.; Bieler, D.; Kollig, E.; Schwab, R. Besonderheiten Und Versorgung Penetrierender Verletzungen Am Beispiel von Schuss—Und Explosionsopfern Ohne Ballistischen Körperschutz in Afghanistan (2009–2013). Zent. Chir. -Z. Allg. Visz. Gefasschir. 2017, 142, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.V.; Burch, J.M.; Spjut-Patrinely, V.; Mattox, K.L.; Jordan, G.L. Abdominal Gunshot Wounds. Ann. Surg. 1988, 208, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, M.; Benjamin, E.; Piccinini, A.; Inaba, K.; Demetriades, D. Gunshot Wounds to the Liver: No Longer a Mandatory Operation. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navsaria, P.H.; Nicol, A.J.; Krige, J.E.; Edu, S. Selective Nonoperative Management of Liver Gunshot Injuries. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F.; Panel, T.W.E.; Coimbra, R.; Ordonez, C.; Kluger, Y.; Vega, F.; Moore, E.E.; Biffl, W.; Peitzman, A.; Horer, T.; et al. Liver Trauma: WSES 2020 Guidelines. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Ng, S.H.; Lee, C.M.; Tsai, C.H. Hepatic Abscess Due to Gastric Perforation by Ingested Fish Bone Demonstrated by Computed Tomography. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 1999, 98, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carver, D.; Bruckschwaiger, V.; Martel, G.; Bertens, K.A.; Abou-Khalil, J.; Balaa, F. Laparoscopic Retrieval of a Sewing Needle from the Liver: A Case Report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 51, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poyanli, A.; Bilge, O.; Kapran, Y.; Güven, K. Foreign Body Granuloma Mimicking Liver Metastasis. Br. J. Radiol. 2005, 78, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | Year | Article Type | Number of Patients | Age | Sex | Foreign Body | Clinical Presentation | Imaging | Duration of Symptoms | Timing | Mode of Entry | Position in the Liver (Lobe) | Surgery | Surgical Complications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nishimoto Y. [14] | 2003 | Case report | 1 | 1 y | M | Sewing needle | Asymptomatic | X-ray | Asymptomatic | Unknown | Unknown | Left | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Discharged on 8th post-op day |

| Thipphavong S. [4] | 2004 | Case report | 1 | 12 y | F | Ventriculoperitoneal shunt | Vomiting and headache, abdominal pain and augmented white blood cell count | CT | 5 d | 4 m | Iatrogenic | Right lobe | Spontaneous passing through the anus | No surgery performed | Asymptomatic at 1-year follow-up |

| Meeks T. [23] | 2004 | Case report | 1 | 22 m | F | Air-powdered pellet | Asymptomatic | X-ray, Angiography | Unknown | Immediately | Penetration | Right | Laparotomy | None | Discharged on 8th post-op day |

| Marya KM. [21] | 2006 | Case report | 1 | 5 y | U | Kirschner wire | Asymptomatic | X-ray, Abdominal US | Unknown | 4 w | Iatrogenic | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Asymptomatic at 1-year follow-up |

| Azili MN. [15] | 2007 | Case report and review of literature | 1 | 14 y | F | Sewing needle | Abdominal pain, fever, increased white blood count | X-ray, Gastroscopy | Unknown | 1 m | Ingestion | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Discharged on 7th post-op day |

| Akçam M. [24] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | 5 y | M | Pin | Asymptomatic | X-ray, Abdominal US | Unknown | 3 m | Ingestion | Unknown | Endoscopic removal | None | Discharged on 1st post-op day |

| Dominguez S. [2] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | 3 y | M | Sewing needle | Asymptomatic | X-ray, Abdominal US, CT | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Caudate | Laparoscopy, extraction | None | Asymptomatic at 19-months follow-up |

| Avcu S. [16] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | 16 y | F | Sewing needle | Abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, increased white blood count, increased AST, ALT, LDH, ALP. | X-ray, Abdominal US, CT | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Unknown |

| Bakal U. [17] | 2012 | Case reports | 1 | 14 y | M | Sewing needle | Abdominal pain and vomiting (simultaneous appendicitis) | X-ray, Abdominal US, CT | 1 d | Unknown | Unknown | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Asymptomatic at 1-year follow-up |

| Xu BJ. [18] | 2013 | Case report | 1 | 5 m | M | Sewing needle | Mild respiratory symptoms, increased white blood count, increased ALT, AST, bilirubin | X-ray, CT | 3 d | Unknown | Unknown | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Asymptomatic at 2-months follow-up |

| Adams S.D. [5] | 2014 | Case report | 1 | 6 y | F | Gastrostomy bumper | Persistent discharge, trouble advancing and rotating the tube, “buried bumper” syndrome | Gastroscopy | 18 m | 3 y | Iatrogenic | Left | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Discharged on 7th post-op day |

| Hyak JM. [22] | 2020 | Retrospective study | 1 | U | U | Pellet fragment | 11 cm liver abscess | Unknown | Unknown | 1 m | Penetration | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Le Mandat-Schultz A. [26] | 2003 | Case report | 1 | 11 m | M | Sewing needle | Cough and vomiting (simultaneous laryngitis) | X-ray, Abdominal US | Unknown | Unknown | Ingestion | Unknown | Laparoscopy, extraction | None | Discharged on 2nd post-op day |

| Demir S. [19] | 2020 | Case report | 1 | 11 y | M | Sewing needle | Left armpit and chest pain | X-ray, Abdominal Ultrasound, CT | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Right | Laparotomy, extraction | None | Asymptomatic at 6-months follow-up |

| Saitua F. [20] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | 3 m | M | Sewing needle | Mild respiratory symptoms (cough and minor respiratory difficulty) | X-ray, Abdominal Ultrasound, CT | 2 d | Unknown | Unknown | Quadrate lobe | Laparotomy and manual extraction | None | Discharged on 3rd post-op day |

| Ariyuca S. [25] | 2009 | Case report | 1 | 16 y | F | Pin | Epigastric pain, abdominal tenderness, anorexia, elevated liver enzymes and white blood count | X-ray, Abdominal Ultrasound | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Left | Unknown | Unknownn | Unknown |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 50% |

| Female | 6 | 37% |

| Unknown | 2 | 13% |

| Type of foreign body | ||

| sewing needle | 9 | 56% |

| pin | 2 | 13% |

| gun pellet | 2 | 13% |

| Medical devices | 3 | 18% |

| Route of access | ||

| Unknwon | 9 | 56% |

| Ingestion | 3 | 19% |

| Penetration | 4 | 25% |

| Clinical presentation | ||

| Asymptomatic | 7 | 44% |

| Abdominal pain | 5 | 31% |

| Vomiting | 4 | 19% |

| Other | 2 | 12% |

| Imaging | ||

| X-ray | 13 | 81% |

| Abdominal Ultrasound | 9 | 56% |

| CT-scan | 7 | 44% |

| Digestive endoscopy | 2 | 13% |

| Angiography | 1 | 6% |

| Unknown | 1 | 6% |

| Position in the liver | ||

| Right lobe | 9 | 56% |

| Left lobe | 3 | 19% |

| Quadrate lobe | 1 | 6% |

| Caudate lobe | 1 | 6% |

| Unknown | 2 | 13% |

| Intervention | ||

| Surgical removal | 12 | 75% |

| Endoscopic removal | 1 | 6% |

| Spontaneus delivery | 1 | 6% |

| Unknown | 2 | 13% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gigola, F.; Grimaldi, C.; Bici, K.; Ghionzoli, M.; Spinelli, C.; Muiesan, P.; Morabito, A. Epidemiology and Surgical Management of Foreign Bodies in the Liver in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Children 2022, 9, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020120

Gigola F, Grimaldi C, Bici K, Ghionzoli M, Spinelli C, Muiesan P, Morabito A. Epidemiology and Surgical Management of Foreign Bodies in the Liver in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Children. 2022; 9(2):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020120

Chicago/Turabian StyleGigola, Francesca, Chiara Grimaldi, Kejd Bici, Marco Ghionzoli, Claudio Spinelli, Paolo Muiesan, and Antonino Morabito. 2022. "Epidemiology and Surgical Management of Foreign Bodies in the Liver in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Children 9, no. 2: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020120

APA StyleGigola, F., Grimaldi, C., Bici, K., Ghionzoli, M., Spinelli, C., Muiesan, P., & Morabito, A. (2022). Epidemiology and Surgical Management of Foreign Bodies in the Liver in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Children, 9(2), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020120