Association between Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after Caesarean Section and Breastfeeding Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Outcome Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Association between SSC after CSs and Breastfeeding Outcomes

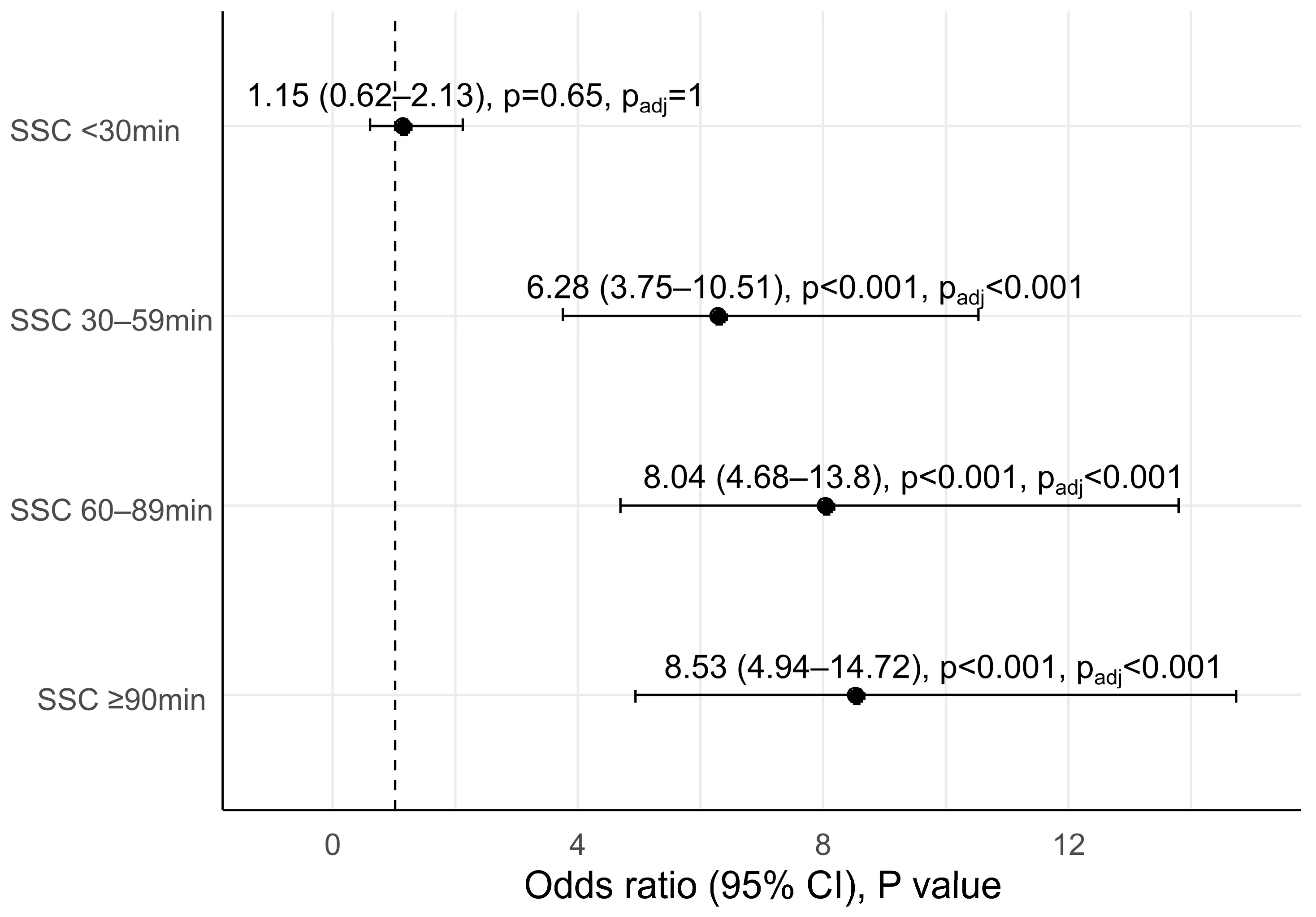

3.2. Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after CSs and Early Initiation of Breastfeeding

3.3. Promoting Factors for Exclusive Breastfeeding at Hospital Discharge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; França, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42590/1/9241562218.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- UNICEF; WHO. Capture the Moment: Early Initiation of Breastfeeding: The Best Start for Every Newborn; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/capture-moment (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Khan, J.; Vesel, L.; Bahl, R.; Martines, J.C. Timing of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding during the first month of life: Effects on neonatal mortality and morbidity--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern. Child Health, J. 2015, 19, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEOVITA Study Group. Timing of initiation, patterns of breastfeeding, and infant survival: Prospective analysis of pooled data from three randomised trials. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e266–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurokhmah, S.; Rahmawaty, S.; Puspitasari, D.I. Determinants of Optimal Breastfeeding Practices in Indonesia: Findings From the 2017 Indonesia Demographic Health Survey. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2022, 55, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. The State of The World’s Children 2021 on My Mind, Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/114636/file/SOWC-2021-full-report-English.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- WHO. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Breastfeeding Policy. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-14.7 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Moore, E.R.; Bergman, N.; Anderson, G.C.; Medley, N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD003519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, K.; Saeed, A.A.; Hasan, S.S.; Moghaddam-Banaem, L. The effect of mother and newborn early skin-to-skin contact on initiation of breastfeeding, newborn temperature and duration of third stage of labor. Int. Breastfeed J. 2018, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.; Tha, P.H.; Ho-Lim, S.S.T.; Wong, L.Y.; Lim, P.I.; Citra Nurfarah, B.Z.M.; Shorey, S. An analysis of the effects of intrapartum factors, neonatal characteristics, and skin-to-skin contact on early breastfeeding initiation. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooijmans, K.H.M.; Beijers, R.; Brett, B.E.; de Weerth, C. Daily skin-to-skin contact in full-term infants and breastfeeding: Secondary outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Luo, S.; Trasande, L.; Hellerstein, S.; Kang, C.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.M.; Blustein, J. Geographic Variations and Temporal Trends in Cesarean Delivery Rates in China, 2008–2014. JAMA 2017, 317, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wan, W.; Zhu, C. Breastfeeding after a cesarean section: A literature review. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, A.J.; Mannion, C.A.; McDonald, S.W.; Brockway, M.; Tough, S.C. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, E.; Santhakumaran, S.; Gale, C.; Philipps, L.H.; Modi, N.; Hyde, M.J. Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; UNICEF. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: The Revised Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513807 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- WHO. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2017: Tracking Progress for Breastfeeding Policies and Programmes. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-breastfeeding-scorecard-2017-tracking-progress-for-breastfeeding-policies-and-programmes (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Qu, W.; Yue, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.L.; Jin, X.; Huang, X.; Tian, X.; Martin, K.; Narayan, A.; Xu, T. Assessing the changes in childbirth care practices and neonatal outcomes in Western China: Pre-comparison and post-comparison study on early essential newborn care interventions. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.; Schmied, V.; Burns, E.; Dahlen, H. Immediate or early skin-to-skin contact after a Caesarean section: A review of the literature. Matern. Child Nutr. 2014, 10, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe-Murray, H.J.; Fisher, J.R. Baby friendly hospital practices: Cesarean section is a persistent barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding. Birth 2002, 29, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Khan, A.N.S.; Tasnim, F.; Chowdhury, M.A.K.; Billah, S.M.; Karim, T.; Arifeen, S.E.; Garnett, S.P. Prevalence and determinants of initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth: An analysis of the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Khan, S.M.; Carvajal-Aguirre, L.; Brodish, P.; Amouzou, A.; Moran, A. The importance of skin-to-skin contact for early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria and Bangladesh. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 020505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mannava, P.; Murray, J.C.S.; Sobel, H.L.; Jatobatu, A.; Calibo, A.; Tsevelmaa, B.; Saysanasongkham, B.; Ogaoga, D.; Waramin, E.J.; et al. Western Pacific Region Early Essential Newborn Care Working Group. Association between early essential newborn care and breastfeeding outcomes in eight countries in Asia and the Pacific: A cross-sectional observational-study. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widström, A.M.; Lilja, G.; Aaltomaa-Michalias, P.; Dahllöf, A.; Lintula, M.; Nissen, E. Newborn behaviour to locate the breast when skin-to-skin: A possible method for enabling early self-regulation. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, S.I.; Molina, C.F.; Gamboa, O.A.; Acuña, E. Comparison of the Effects of Different Skin-to-Skin Contact Onset Times on Breastfeeding Behavior. Breastfeed Med. 2021, 16, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwedberg, S.; Blomquist, J.; Sigerstad, E. Midwives’ experiences with mother-infant skin-to-skin contact after a caesarean section: ‘fighting an uphill battle’. Midwifery 2015, 31, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, F.Z.; Sadeghi, R.; Maleki-Saghooni, N.; Khadivzadeh, T. The effect of mother-infant skin to skin contact on success and duration of first breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, R.; Piccinini-Vallis, H.; Woolcott, C. The relationship between skin-to-skin contact and rates of exclusive breastfeeding at four months among a group of mothers in Nova Scotia: A retrospective cohort study. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No SSC (n = 136) | SSC Duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 min (n = 84) | 30–59 min (n = 168) | 60–89 min (n = 146) | ≥90 min (n = 145) | F/χ2 | p | ||

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 32.06 ± 4.66 | 32.06 ± 4.89 | 32.73 ± 4.46 | 32.21 ± 4.12 | 32.43 ± 4.19 | 0.59 | 0.67 |

| Delivery gestational week (median (IQR), weeks) | 39.14 (38.71–39.43) | 39.29 (38.86–39.57) | 39.14 (38.71–39.43) | 39.00 (38.71–39.46) | 39.00 (38.71–39.43) | 0.14 | |

| Gravidity (median (IQR), times) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.33 | |

| Parity (median (IQR), times) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 0.92 | |

| Education level (n (%)) | 5.80 | 0.67 | |||||

| High school and less | 28 (20.9%) | 19 (22.9%) | 27 (16.6%) | 21 (14.4%) | 25 (17.4%) | ||

| College | 84 (62.7%) | 52 (62.7%) | 112 (68.7%) | 96 (65.8%) | 99 (68.8%) | ||

| Graduate and above | 22 (16.4%) | 15 (14.5%) | 24 (14.7%) | 29 (19.9%) | 20 (13.9%) | ||

| Height (mean ± SD, cm) | 161.70 ± 4.81 | 161.44 ± 5.23 | 161.13 ± 4.90 | 160.66 ± 5.11 | 160.77 ± 4.90 | 1.05 | 0.38 |

| Weight before delivery (mean ± SD, kg) | 72.87 ± 10.18 | 72.94 ± 10.43 | 71.52 ± 8.66 | 69.81 ± 8.78 | 71.22 ± 8.95 | 2.47 | 0.05 |

| Neonatal Characteristics | |||||||

| Birth weight (mean ± SD, g) | 3358.75 ± 396.15 | 3515.00 ± 443.41 | 3409.04 ± 383.94 | 3443.17 ± 444.90 | 3403.99 ± 385.05 | 2.11 | 0.08 |

| Gender (n (%)) | 2.53 | 0.64 | |||||

| Female | 67 (49.6%) | 39 (46.4%) | 77 (45.8%) | 68 (46.6%) | 78 (53.8%) | ||

| Male | 68 (50.4%) | 45 (53.6%) | 91 (54.2%) | 78 (53.4%) | 67 (46.2%) | ||

| Birth length (mean ± SD, cm) | 49.57 ± 1.43 | 49.73 ± 1.39 | 49.48 ± 1.39 | 49.64 ± 1.58 | 49.58 ± 1.34 | 0.51 | 0.73 |

| Admitted to NICU or neonatal ward (n (%)) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2.54 | 0.64 |

| No SSC | SSC Duration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 min | 30–59 min | 60–89 min | ≥90 min | F/χ2 | p | Padj | ||

| Early initiation of breastfeeding, n (%) | 37 (27.2%) | 25 (29.8%) | 116 (69.0%) | 108 (74.0%) | 108 (74.5%) | 120.34 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Time to exhibition of feeding cues (median (IQR), min) | 34.1 (21.4, 51.4) | 18.2 (10.6, 35.9) | 16.0 (10.0, 24.7) | 14.0 (7.8, 26.8) | 19.1 (9.9, 38.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Time to initiation of breastfeeding (median (IQR), min) | 74.0 (60.0, 91.0) | 68.5 (55.3, 89.0) | 40.5 (24.0, 64.0) | 38.5 (21.0, 62.3) | 48.0 (30.0, 61.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge, n (%) | 70 (51.5%) | 52 (61.9%) | 111 (66.1%) | 94 (64.4%) | 100 (69.0%) | 10.80 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Mixed feeding at hospital discharge, n (%) | 65 (47.8%) | 30 (35.7%) | 57 (33.9%) | 51 (34.9%) | 44 (30.3%) | |||

| Formula feeding at hospital discharge, n (%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | |||

| The age of the infant at discharge (median (IQR), day) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 5(4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 12.64 | 0.013 | 0.052 |

| Model 1 * | Model 2 † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Maternal age (years) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.93 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.89 |

| Multiparity | 1.63 (1.19, 2.25) | 0.002 | 1.34 (0.94, 1.89) | 0.10 |

| Maternal weight before delivery (kg) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | <0.001 |

| Macrosomia | 0.38 (0.23, 0.64) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.31, 0.92) | 0.03 |

| SSC duration | ||||

| No SSC at birth | 1(Ref.) | 1(Ref.) | ||

| SSC duration <30 min | 1.53 (0.88, 2.67) | 0.13 | 1.62 (0.91, 2.86) | 0.10 |

| SSC duration 30–59 min | 1.84 (1.16, 2.92) | 0.01 | 1.86 (1.15, 3.01) | 0.01 |

| SSC duration 60–89 min | 1.70 (1.06, 2.75) | 0.03 | 1.79 (1.09, 2.91) | 0.02 |

| SSC duration ≥90 min | 2.10 (1.29, 3.41) | 0.003 | 2.16 (1.31, 3.56) | 0.002 |

| Time to exhibition of feeding cues (min) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.70 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.55 |

| Time to initiation of breastfeeding (min) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.38 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.40 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juan, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Tan, L.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, H. Association between Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after Caesarean Section and Breastfeeding Outcomes. Children 2022, 9, 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111742

Juan J, Zhang X, Wang X, Liu J, Cao Y, Tan L, Gao Y, Qiu Y, Yang H. Association between Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after Caesarean Section and Breastfeeding Outcomes. Children. 2022; 9(11):1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111742

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuan, Juan, Xiaosong Zhang, Xueyin Wang, Jun Liu, Yinli Cao, Ling Tan, Yan Gao, Yinping Qiu, and Huixia Yang. 2022. "Association between Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after Caesarean Section and Breastfeeding Outcomes" Children 9, no. 11: 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111742

APA StyleJuan, J., Zhang, X., Wang, X., Liu, J., Cao, Y., Tan, L., Gao, Y., Qiu, Y., & Yang, H. (2022). Association between Skin-to-Skin Contact Duration after Caesarean Section and Breastfeeding Outcomes. Children, 9(11), 1742. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111742