Childhood Diarrhea Prevalence and Uptake of Oral Rehydration Solution and Zinc Treatment in Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Explanatory Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Childhood Diarrhea

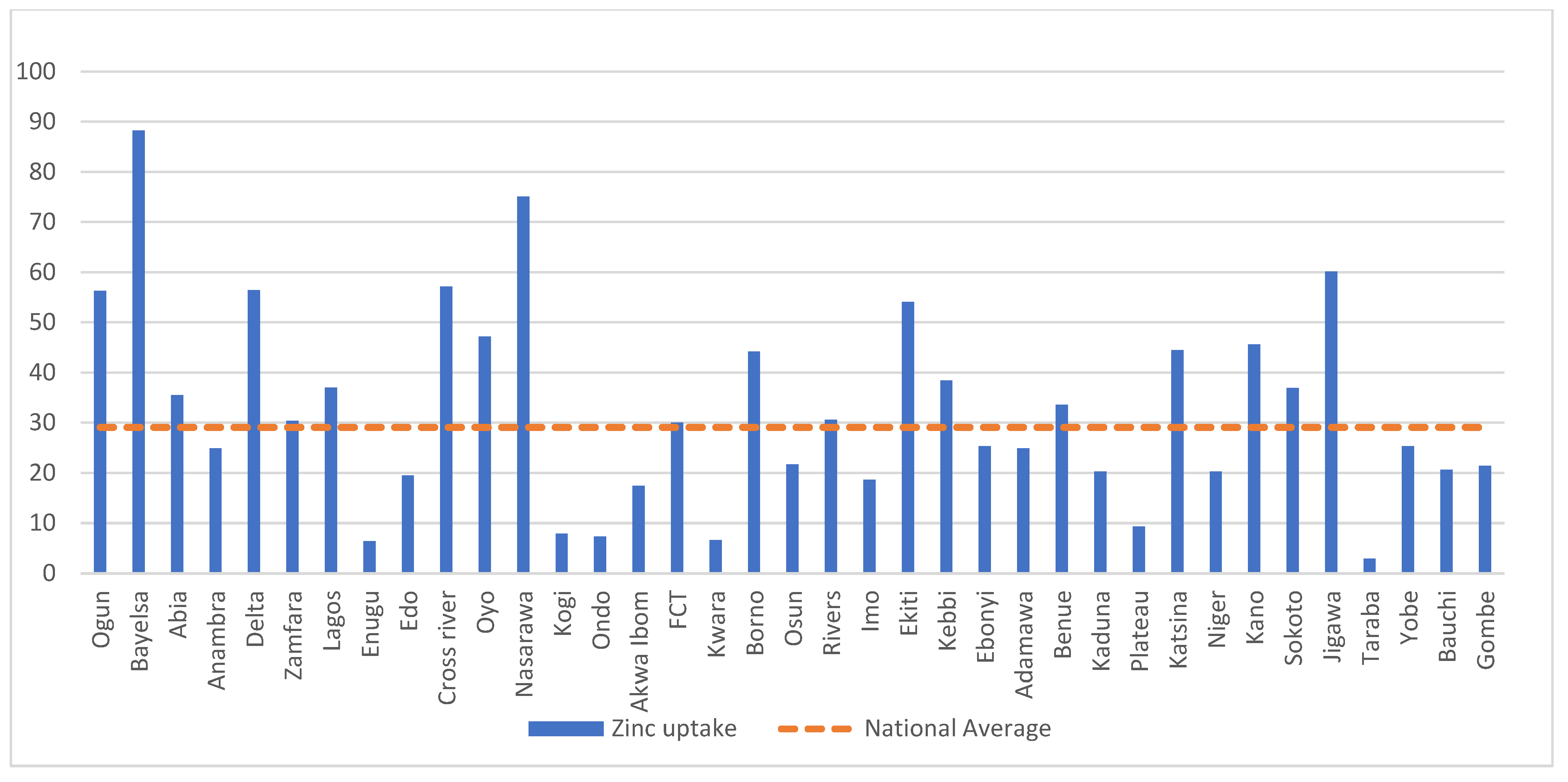

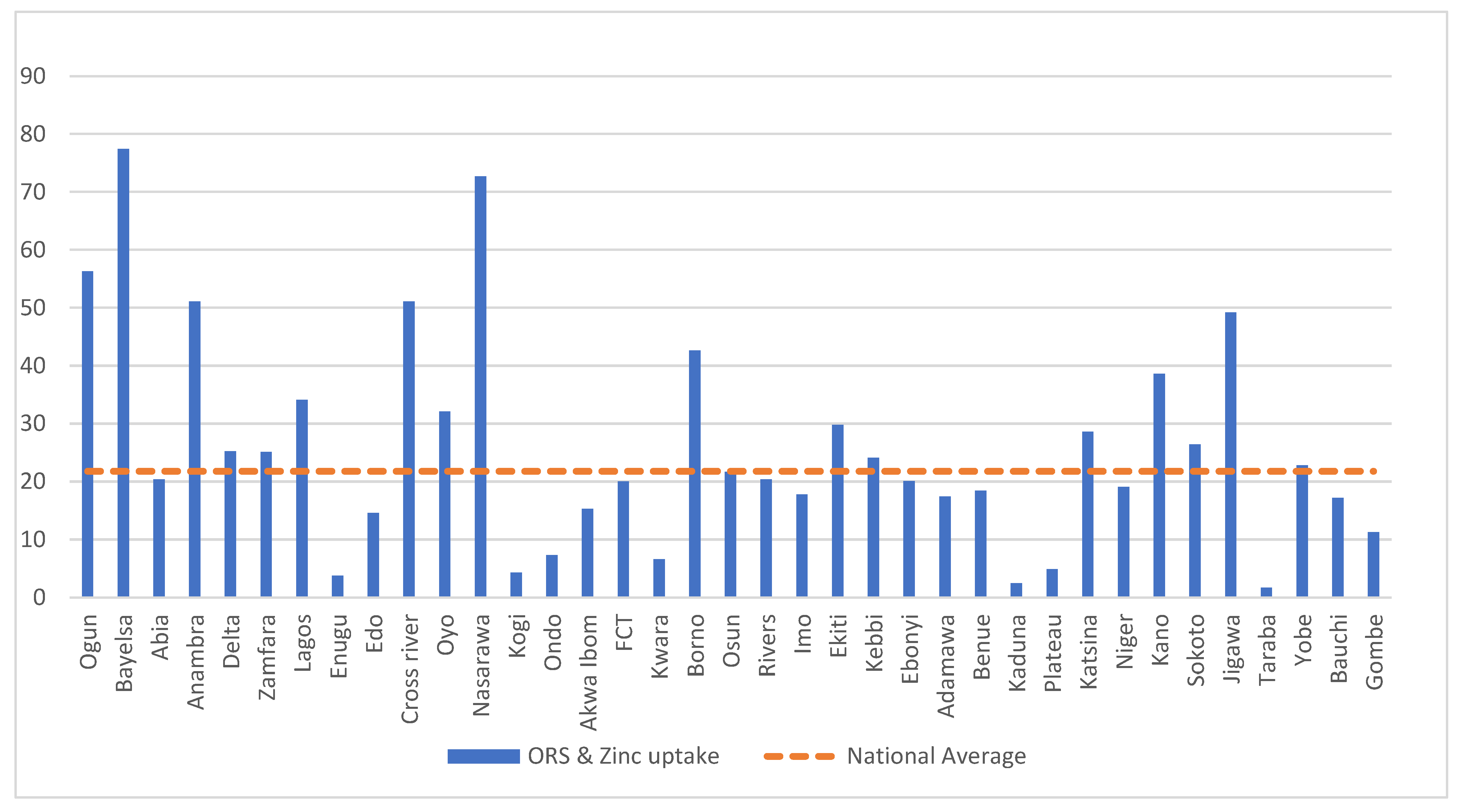

3.2. Uptake of ORS and Zinc Supplements for Treatment of Childhood Diarrhea

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Region/State | Percent of Children under 5 That Had Diarrhea Episode 2 Weeks before the Survey (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| North Central | 11.4 (10.4,12.4) |

| Benue | 11.2 (9.1, 13.6) |

| Kogi | 6.6 (4.8, 9.1) |

| Kwara | 8.3 (6.0, 11.4) |

| Nasarawa | 5.7 (3.9, 8.3) |

| Niger | 16.3 (14.1, 18.8) |

| Plateau | 13.3 (10.9, 16.1) |

| FCT | 8.2 (6.2, 10.7) |

| Northeast | 24.6 (23.4, 25.9) |

| Adamawa | 10.7 (8.3, 13.6) |

| Bauchi | 34.1 (31.5, 36.9) |

| Borno | 8.9 (7.0, 11.2) |

| Gombe | 35.0 (32.1, 38.0) |

| Taraba | 23.1 (20.5, 26.0) |

| Yobe | 33.4 (30.0, 37.0) |

| Northwest | 13.8 (13.0, 14.6) |

| Kaduna | 11.8 (9.9, 14.0) |

| Kano | 17.7 (15.9, 19.6) |

| Katsina | 13.7 (11.9, 15.7) |

| Jigawa | 19.1 (16.9, 21.4) |

| Kebbi | 9.6 (8.0, 11.6) |

| Sokoto | 18.5 (15.9, 21.3) |

| Zamfara | 3.9 (2.7, 5.5) |

| Southeast | 6.1 (5.3.7.0) |

| Anambra | 3.1 (2.2, 4.5) |

| Abia | 3.0 (1.9, 4.7) |

| Ebonyi | 10.5 (8.6, 12.8) |

| Enugu | 4.1 (2.6, 6.2) |

| Imo | 9.1 (6.9, 11.8) |

| South | 6.1 (5.1, 7.2) |

| Akwa Ibom | 8.1 (6.0, 11.0) |

| Bayelsa | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) |

| Delta | 3.8 (2.2, 6.5) |

| Edo | 4.3 (2.7, 7.0) |

| Cross River | 4.5 (2.7, 7.4) |

| Rivers | 9.0 (6.9, 11.7) |

| Southwest | 5.2 (4.4, 6.1) |

| Ogun | 0.9 (0.3, 2.3) |

| Ondo | 6.9 (5.0, 9.4) |

| Oyo | 5.7 (3.9, 8.3) |

| Osun | 9.0 (6.6, 12.1) |

| Lagos | 3.9 (2.8, 5.6) |

| Ekiti | 9.3 (6.2, 13.7) |

| Nigeria | 12.9 (12.5, 13.5) |

| Region/State | Percent of Children Given Zinc Supplement at Episode of Diarrhea (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| North Central | 22.9 (19.3, 27.1) |

| Benue | 33.6 (24.5, 44.1) |

| Kogi | 7.9 (2.5, 22.5) |

| Kwara | 6.6 (2.1, 18.7) |

| Nasarawa | 75.1 (55.8, 87.8) |

| Niger | 20.3 (14.8, 27.2) |

| Plateau | 9.3 (4.5, 18.1) |

| FCT | 30.0 (18.0, 45.6) |

| Northeast | 22.0 (19.5, 24.6) |

| Adamawa | 24.9 (14.9, 38.6) |

| Bauchi | 20.6 (17.0, 24.8) |

| Borno | 44.2 (32.4, 56.7) |

| Gombe | 21.4 (17.4, 26.2) |

| Taraba | 2.9 (13.9, 6.2) |

| Yobe | 25.3 (19.8, 31.7) |

| Northwest | 41.9 (38.9, 44.9) |

| Kaduna | 20.3 (13.2, 29.8) |

| Kano | 45.6 (40.0, 51.3) |

| Katsina | 44.5 (37.3, 51.9) |

| Jigawa | 60.1 (53.6, 66.3) |

| Kebbi | 38.4 (29.2, 48.4) |

| Sokoto | 36.9 (29.5, 45.0) |

| Zamfara | 30.4 (15.8, 50.4) |

| Southeast | 27.5 (21.8, 34.1) |

| Anambra | 58.0 (39.2, 74.8) |

| Abia | 35.5 (17.5, 58.8) |

| Ebonyi | 25.3 (17.5, 35.2) |

| Enugu | 6.4 (15.4, 23.2) |

| Imo | 18.6 (10.1, 31.9) |

| South | 32.7 (25.4, 41.1) |

| Akwa Ibom | 17.4 (7.5, 35.4) |

| Bayelsa | 77.4 (39.7, 94.7) |

| Delta | 56.4 (29.8, 79.7) |

| Edo | 19.5 (7.7, 41.2) |

| Cross River | 57.1 (31.2, 79.6) |

| Rivers | 30.6 (20.0, 43.6) |

| Southwest | 35.1 (27.4, 43.6) |

| Ogun | 56.3 (15.2, 90.3) |

| Ondo | 7.3 (1.8, 24.6) |

| Oyo | 47.2 (29.1, 66.0) |

| Osun | 21.7 (11.1, 38.1) |

| Lagos | 37.0 (22.1, 54.9) |

| Ekiti | 54.1 (34.0, 72.9) |

| Nigeria | 29.1 (27.7, 30.5) |

| Region/State | Percent of Children Given ORS at Episode of Diarrhea (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| North Central | 40.8 (36.2, 45.5) |

| Benue | 45.6 (35.3, 56.3) |

| Kogi | 37.4 (23.2, 54.2) |

| Kwara | 35.3 (20.6, 53.5) |

| Nasarawa | 82.9 (61.9, 93.5) |

| Niger | 42.0 (34.6, 49.8) |

| Plateau | 18.4 (11.2, 28.5) |

| FCT | 48.1 (34.2, 62.2) |

| Northeast | 38.2 (35.3, 41.1) |

| Adamawa | 42.1 (30.2, 55.1) |

| Bauchi | 36.5 (31.9, 41.3) |

| Borno | 82.7 (72.8, 89.5) |

| Gombe | 26.1 (21.8, 31.0) |

| Taraba | 10.0 (6.6, 14.9) |

| Yobe | 46.2 (39.7, 52.9) |

| Northwest | 43.4 (40.4, 46.4) |

| Kaduna | 5.1 (2.8, 8.9) |

| Kano | 55.1 (49.3, 60.7) |

| Katsina | 40.4 (33.4, 47.9) |

| Jigawa | 63.9 (57.4, 69.9) |

| Kebbi | 41.9 (32.6, 51.8) |

| Sokoto | 47.9 (40.0, 60.0) |

| Zamfara | 33.2 (18.0, 53.0) |

| Southeast | 44.9 (38.2, 51.8) |

| Anambra | 68.9 (48.9, 83.7) |

| Abia | 40.6 (20.8, 63.9) |

| Ebonyi | 41.5 (31.6, 52.2) |

| Enugu | 26.1 (11.9, 48.1) |

| Imo | 43.4 (30.9, 56.8) |

| South | 44.6 (36.3, 53.1) |

| Akwa Ibom | 30.8 (17.8, 47.9) |

| Bayelsa | 77.4 (39.7, 94.7) |

| Delta | 59.2 (32.2, 81.6) |

| Edo | 48.5 (26.1, 71.5) |

| Cross River | 66.1 (41.1, 84.5) |

| Rivers | 41.7 (29.3, 55.2) |

| Southwest | 52.9 (44.7, 60.9) |

| Ogun | 80.7 (30.2, 97.6) |

| Ondo | 35.4 (21.5, 52.4) |

| Oyo | 55.2 (35.9, 72.9) |

| Osun | 47.2 (32.1, 62.8) |

| Lagos | 65.2 (47.8, 79.3) |

| Ekiti | 44.6 (25.6, 65.4) |

| Nigeria | 39.7 (38.2, 41.3) |

References

- Paulson, K.R.; Kamath, A.M.; Alam, T.; Bienhoff, K.; Abady, G.G.; Abbas, J.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abd-Elsalam, S.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 for neonatal and child health: All-cause and cause-specific mortality findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 398, 870–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Results Tool. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Global Health Data Exchange. GBD Results Tool GHDx. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Jiwok, J.C.; Adebowale, A.S.; Wilson, I.; Kancherla, V.; Umeokonkwo, C.D. Patterns of diarrhoeal disease among under-five children in Plateau State, Nigeria, 2013–2017. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Population Prospect 2019. Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1000 live births)—Nigeria Data (worldbank.org). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?locations=NG (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- UNICEF. Diarrhea. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- WHO. Diarrhea. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/diarrhoea (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Schroder, K.; Battu, A.; Wentworth, L.; Houdek, J.; Fashanu, C.; Wiwa, O.; Kihoto, R.; Macharia, G.; Trikha, N.; Bahuguna, P.; et al. Increasing coverage of pediatric diarrhea treatment in high-burden countries. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, T.A.; Chandyo, R.K.; Bahl, R.; Sharma, P.R.; Adhikari, R.K.; Bhandari, N.; Ulvik, R.J.; Mølbak, K.; Bhan, M.K.; Sommerfelt, H. Effectiveness and efficacy of zinc for the treatment of acute diarrhea in young children. Pediatrics 2002, 109, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Population Commission Nigeria (NPC); ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018; National Population Commission Nigeria (NPC): Abuja, Nigeria; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 159, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software, Release 12; StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Apanga, P.A.; Kumbeni, M.T. Factors associated with diarrhea and acute respiratory infection in children under-5 years old in Ghana: An analysis of a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatyaa, D.M.; Ochieng, C. Disease burden and risk factors of diarrhoea in children under five years: Evidence from Kenya’s demographic health survey 2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omona, S.; Malinga, G.M.; Opoke, R.; Openy, G.; Opiyo, R. Prevalence of diarrhoea and associated risk factors among children under five years old in Pader District, northern Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, N.M.; Lynch, K.F.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Lönnrot, M.; Virtanen, S.M.; Hyöty, H.; Norris, J.M. The relationship between breastfeeding and reported respiratory and gastrointestinal infection rates in young children. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosek, M.; Bern, C.; Guerrant, R.L. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003, 8, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ygberg, S.; Nilsson, A. The developing immune system—From foetus to toddler. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, S.; Pierre, A.; Calder, P.C. Immune Function and Micronutrient Requirements Change over the Life Course. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, P.; Azage, M. Geographical Variations and Factors Associated with Childhood Diarrhea in Tanzania: A National Population Based Survey 2015–16. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2019, 29, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berde, A.S.; Yalçın, S.S.; Özcebe, H.; Üner, S.; Karadağ-Caman, Ö. Determinants of childhood diarrhea among under-five year old children in Nigeria: A population-based study using the 2013 demographic and health survey data. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2018, 60, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.; Taha, M.; Kassahun, W. Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease in underfive children among health extension model and non-model families in Sheko district rural community, Southwest Ethiopia: Comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.; Abdulwahab, A.; Houdek, J.; Adekeye, O.; Abubakar, M.; Akinjeji, A.; Braimoh, T.; Ajeroh, O.; Stanley, M.; Goh, N.; et al. Program evaluation of an ORS and zinc scale-up program in 8 Nigerian states. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.O.O.; Alawad, M.O.A.; Ahmed, A.A.M.; Mahmoud, A.A.A. Access to oral rehydration solution and zinc supplementation for treatment of childhood diarrhoeal diseases in Sudan. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, N.B.; Atteraya, M.S. Oral rehydration salts therapy use among children under five years of age with diarrhea in Ethiopia. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshaw, Y.; Worku, M.G.; Tessema, Z.T.; Teshale, A.B.; Tesema, G.A. A Zinc utilization and associated factors among under-five children with diarrhea in East Africa: A generalized linear mixed modeling. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolurin, O.O.; Olaleye, A.O.; Adekoya, A.O. Addressing the Sub-Optimal Use of Oral Rehydration Solution for Childhood Diarrhoea in the Tropics: Findings from a Rural Setting in Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2020, 67, fmaa071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunrinde, O.G.; Raji, T.; Owolabi, O.A.; Anigo, K.M. Knowledge. Attitude and Practice of Home Management of Childhood Diarrhoea among Caregivers of Under-5 Children with Diarrhoeal Disease in Northwestern Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2012, 58, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olopha, O.O.; Egbewale, B. Awareness and Knowledge of Diarrhoeal Home Management among Mothers of Under-five in Ibadan, Nigeria. Univers. J. Public Health 2020, 5, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breastfeeding Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/faq/index.htm#howlong (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Fewtrell, M.S.; Morgan, J.B.; Duggan, C.; Gunnlaugsson, G.; Hibberd, P.L.; Lucas, A.; Kleinman, R.E. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: What is the evidence to support current recommendations? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 635S–638S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children under 5 Years of Age | Children under 5 Years of Age with Reported Diarrhea in the Last Two Weeks | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Child Characteristics | ||

| Child age (months) | ||

| <6 | 3250 (10.58) | 324 (8.19) |

| 6–11 | 3149 (10.25) | 641 (16.20) |

| 12–23 | 6059 (19.73) | 1229 (31.07) |

| 24–35 | 5834 (19.00) | 800 (20.22) |

| 36–47 | 6168 (20.08) | 560 (14.16) |

| 48–59 | 6253 (20.36) | 402 (10.16) |

| Child sex | ||

| Male | 15,537 (50.59) | 2015 (50.94) |

| Female | 15,176 (49.41) | 1941 (49.06) |

| Birth order | ||

| First | 5885 (16.16) | 684 (17.29) |

| Second/Third | 10,504 (34.20) | 1228 (31.04) |

| Fourth/Fifth | 7202 (23.45) | 883 (22.32) |

| Sixth and above | 7122 (23.19) | 1161 (29.35) |

| Place of delivery | ||

| Non-institutional | 18,277 (59.51) | 2776 (70.71) |

| Institutional | 12,436 (40.49) | 1180 (29.83) |

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Maternal age (years) | ||

| <20 | 1289 (4.19) | 246 (6.22) |

| 20–34 | 21,583 (70.27) | 2805 (70.90) |

| 35–49 | 7844 (25.54) | 905 (22.88) |

| Current marital status | ||

| Never in union | 645 (2.10) | 59 (1.49) |

| Married/living with partner | 29,181 (95.01) | 3799 (96.03) |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 887 (2.89) | 98 (2.48) |

| Maternal education | ||

| No education | 13,527 (44.04) | 2248 (56.83) |

| Primary | 4776 (15.55) | 614 (15.52) |

| Secondary | 9913 (32.28) | 931 (23.53) |

| Higher | 2497 (8.13) | 163 (4.12) |

| Mother currently working | ||

| No | 9949 (32.39) | 1353 (34.20) |

| Yes | 20,764 (67.61) | 2603 (65.80) |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 10,851 (35.33) | 1098 (27.76) |

| Rural | 19,862 (64.67) | 2858 (72.24) |

| Religion of mother | ||

| Catholic | 2744 (8.93) | 215 (5.43) |

| Other Christian | 9594 (31.24) | 722 (18.25) |

| Islam | 18,113 (58.98) | 3009 (76.06) |

| Traditionalist | 108 (0.35) | 8 (0.20) |

| Other | 154 (0.50) | 2 (0.05) |

| Ethnicity of mother | ||

| Hausa | 9576 (31.18) | 1511 (38.20) |

| Fulani | 2884 (9.39) | 675 (17.06) |

| Ekoi | 144 (0.47) | 10 (0.25) |

| Ibibio | 440 (1.43) | 32 (0.81) |

| Igala | 288 (0.94) | 17 (0.4 3) |

| Igbo | 4200 (13.67) | 276 (6.98) |

| Ijaw/Izion | 750 (2.44) | 19 (0.48) |

| Kanuri/Beriberi | 746 (2.43) | 113 (2.86) |

| Tiv | 723 (2.35) | 68 (1.72) |

| Yoruba | 3037 (9.89) | 186 (4.70) |

| Other | 7925 (25.80) | 1048 (26.52) |

| Source of drinking water | ||

| Unimproved | 12,058 (39.26) | 1814 (45.85) |

| Improved | 18,655 (60.74) | 2142 (54.15) |

| Toilet facility | ||

| Unimproved | 15,644 (50.94) | 2162 (54.65) |

| Improved | 15,069 (49.06) | 1794 (45.35) |

| Presence of water at hand washing place | ||

| Water not available | 9577 (39.41) | 1350 (44.44) |

| Water available | 14,727 (60.59) | 1688 (55.56) |

| Missing | 6409 (20.87) | |

| Soap or detergent present at handwashing place | ||

| No | 16,658 (68.54) | 2348 (77.29) |

| Yes | 7646 (31.46) | 690 (22.71) |

| Missing | 6409 (20.87) | |

| Sex of household head | ||

| Male | 27,776 (90.44) | 3685 (93.15) |

| Female | 2937 (9.56) | 271 (6.85) |

| Household wealth quintile | ||

| Poorest | 7081 (23.06) | 1303 (32.94) |

| Poorer | 6839 (22.27) | 1031 (26.06) |

| Middle | 6509 (21.19) | 776 (19.62) |

| Richer | 5747 (18.71) | 552 (13.95) |

| Richest | 4537 (14.77) | 294 (7.43) |

| Region | ||

| North Central | 5403 (17.59) | 554 (14.00) |

| Northeast | 6481 (21.10) | 1580 (39.94) |

| Northwest | 8934 (29.09) | 1234 (31.19) |

| Southeast | 3545 (11.54) | 232 (5.86) |

| South | 3021 (9.84) | 162 (4.10) |

| Southwest | 3329 (10.84) | 194 (4.90) |

| N | Univariable Relative Risk (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariable Relative Risk (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child characteristics | |||||

| Child’s age (months) | |||||

| <6 | 3250 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 6–11 | 3149 | 2.04 (1.8, 2.31) | <0.001 | 2.02 (1.77, 2.32) | <0.001 |

| 12–23 | 6059 | 2.03 (1.81, 2.28) | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.80, 2.32) | <0.001 |

| 24–35 | 5834 | 1.38 (1.22, 1.55) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.20, 1.58) | <0.001 |

| 36–47 | 6168 | 0.91 (0.80, 1.04) | 0.159 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.05) | 0.174 |

| 48–59 | 6253 | 0.64 (0.56, 0.74) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.59, 0.81) | <0.001 |

| Sex of child | |||||

| Male | 15,537 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 15,176 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.04) | 0.639 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.428 |

| Birth order | |||||

| First | 5885 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second/Third | 10,504 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | 0.896 | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) | 0.856 |

| Fourth/Fifth | 7202 | 1.05 (0.96, 1.16) | 0.264 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.12) | 0.795 |

| Sixth and above | 7122 | 1.40 (1.28,1.53) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | 0.006 |

| Place of Delivery | |||||

| Non-institutional | 18,277 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Institutional | 12,436 | 0.62 (0.59, 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) | 0.097 |

| Maternal characteristics | |||||

| Maternal age (in years) | |||||

| <20 | 1289 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 20–34 | 21,583 | 0.68 (0.60, 0.76) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.75, 1.00) | 0.055 |

| 35–49 | 7844 | 0.60 (0.53, 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.64, 0.91) | 0.002 |

| Current marital status | |||||

| Never in union | 645 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Married/living with partner | 29,181 | 1.42 (1.11, 1.82) | 0.005 | 0.97 (0.89, 0.07) | 0.05 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 887 | 1.20 (0.89, 1.64) | 0.227 | 1.01 (0.89, 0.16) | 0.29 |

| Maternal education | |||||

| No education | 13,527 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Primary | 4776 | 0.77 (0.71, 0.84) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.05, 1.28) | 0.002 |

| Secondary | 9913 | 0.56 (0.52, 0.61) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 0.006 |

| Higher | 2497 | 0.39 (0.34, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.79, 1.18) | 0.756 |

| Mother currently working | |||||

| No | 9949 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 20,764 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98) | 0.009 | 1.25 (1.17, 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Household characteristics | |||||

| Place of residence | |||||

| Urban | 10,851 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 19,862 | 1.42 (1.33, 1.52) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.84, 0.99) | 0.043 |

| Religion | |||||

| Catholic | 2744 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other Christian | 9594 | 0.96 (0.82, 1.11) | 0.589 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.08) | 0.265 |

| Islam | 18,113 | 2.12 (1.86, 2.42) | <0.001 | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) | 0.067 |

| Traditionalist | 108 | 0.94 (0.48, 1.86) | 0.871 | 1.15 (0.59, 2.24) | 0.682 |

| Other | 154 | 0.17 (0.04, 0.66) | 0.011 | 0.39 (0.09, 1.64) | 0.199 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hausa | 9576 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Fulani | 2884 | 1.48 (1.37, 1.61) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.99, 1.23) | 0.053 |

| Ekoi | 144 | 0.44 (0.24, 0.80) | 0.007 | 0.99 (0.52, 1.90) | 0.981 |

| Ibibio | 440 | 0.46 (0.33, 0.66) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.66, 1.77) | 0.755 |

| Igala | 288 | 0.37 (0.24, 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.35, 1.02) | 0.057 |

| Igbo | 4200 | 0.42 (0.37, 0.47) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.64, 1.22) | 0.429 |

| Ijaw/Izon | 750 | 0.16 (0.10, 0.25) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.16, 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Kanuri/beriberi | 746 | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) | 0.649 | 0.74 (0.60, 0.91) | 0.004 |

| Tiv | 723 | 0.60 (0.47, 0.75) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.66, 1.17) | 0.375 |

| Yoruba | 3037 | 0.39 (0.33, 0.50) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.60, 0.95) | 0.018 |

| Other | 7897 | 0.84 (0.78, 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | 0.005 |

| Do not know | 28 | 0.23 (0.03, 1.55) | 0.13 | 0.60 (0.09, 3.99) | 0.596 |

| Sources of drinking water | |||||

| Unimproved | 12,058 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Improved | 18,655 | 0.76 (0.72, 0.81) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.13) | 0.132 |

| Toilet facility | |||||

| Unimproved | 15,644 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Improved | 15,069 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) | 0.109 |

| Presence of water at hand washing place | |||||

| Water not available | 9577 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Water available | 14,727 | 0.81 (0.76, 0.87) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16) | 0.032 |

| Missing | 6409 | 1.02 (0.93, 1.10) | 0.708 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 0.316 |

| Soap or detergent present at handwashing place | |||||

| No | 16,658 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7646 | 0.64 (0.59, 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.06) | 0.52 |

| Missing | 6409 | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) | 0.68 | - | - |

| Sex of household head | |||||

| Male | 27,776 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 2937 | 0.70 (0.61, 0.78) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) | 0.128 |

| Wealth quintile | |||||

| Poorest | 7081 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Poorer | 6839 | 0.82 (0.76, 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.214 |

| Middle | 6509 | 0.65 (0.60, 0.70) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.78, 0.97) | 0.015 |

| Richer | 5747 | 0.52 (0.47, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) | 0.006 |

| Richest | 4537 | 0.35 (0.31, 0.40) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||

| North Central | 5403 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Northeast | 6481 | 2.38 (2.17, 2.60) | <0.001 | 2.06 (1.83, 2.31) | <0.001 |

| Northwest | 8934 | 1.35 (1.23, 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | 0.789 |

| Southeast | 3545 | 0.63 (0.55, 0.74) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.49, 0.94) | 0.02 |

| South | 3021 | 0.52 (0.44, 0.62) | 0.97 | 0.65 (0.50, 0.85) | 0.002 |

| Southwest | 3329 | 0.57 (0.48, 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.50, 0.78) | <0.001 |

| Characteristics | N | ORS | Zinc | ORS and Zinc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariable Relative Risk (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariable Relative Risk (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariable Relative Risk (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Child’s age in Months | |||||||

| <6 | 324 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 6–11 | 641 | 1.34 (1.11, 1.62) | 0.002 | 1.56 (1.21, 2.02) | 0.001 | 1.53 (1.12, 2.09) | 0.006 |

| 12–23 | 1229 | 1.48 (1.24, 1.76) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.36, 2.21) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.30, 2.31) | <0.001 |

| 24–35 | 800 | 1.36 (1.13, 1.63) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.25, 2.07) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.15, 2.09) | 0.004 |

| 36–47 | 560 | 1.30 (1.07, 1.58) | 0.009 | 1.54 (1.21, 2.04) | 0.001 | 1.49 (1.09, 2.04) | 0.014 |

| 48–59 | 402 | 1.29 (1.05, 1.59) | 0.016 | 1.58 (1.20, 2.08) | 0.001 | 1.56 (1.12, 2.16) | 0.008 |

| Sex of child | |||||||

| Male | 2015 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Female | 1941 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.62) | 0.565 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 0.832 | 1.12 (1.00, 1.26) | 0.052 |

| Birth order | |||||||

| First | 684 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Second/Third | 1228 | 1.06 (0.94, 1.20) | 0.934 | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | 0.798 | 1.01 (0.83, 1.23) | 0.918 |

| Fourth/Fifth | 883 | 1.01 (0.88,1.16) | 0.884 | 1.12 (0.94, 1.33) | 0.195 | 1.07 (0.88, 1.33) | 0.474 |

| Sixth and above | 1161 | 1.07 (0.92, 1.23) | 0.918 | 1.05 (0.87, 1.27) | 0.585 | 0.99 (0.79, 1.25) | 0.934 |

| Place of Delivery | |||||||

| Non-institutional | 2776 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Institutional | 1180 | 1.25 (1.14, 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.11, 1.39) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.09, 1.44) | 0.001 |

| Maternal age (in years) | |||||||

| <20 | 246 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 20–34 | 2805 | 1.10 (0.90, 1.35) | 0.338 | 1.19 (0.92, 1.54) | 0.189 | 1.34 (0.96, 1.86) | 0.084 |

| 35–49 | 905 | 0.97 (0.77, 1.23) | 0.8 | 1.14 (0.85, 1.53) | 0.383 | 1.24 (0.86, 1.80) | 0.254 |

| Current marital status | |||||||

| Never in union | 59 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Married/living with partner | 3799 | 1.13 (0.76, 1.66) | 0.551 | 1.26 (0.74, 2.14) | 0.402 | 1.39 (0.67, 2.76) | 0.398 |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 98 | 1.12 (0.71, 1.75) | 0.626 | 1.27 (0.69, 2.34) | 0.444 | 1.29 (0.58,2.86) | 0.536 |

| Maternal educational level | |||||||

| No education | 2248 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Primary | 614 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) | 0.772 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.11) | 0.517 | 0.93 (0.78, 1.12) | 0.458 |

| Secondary | 931 | 0.88 (0.77, 0.99) | 0.039 | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) | 0.538 | 0.92 (0.76, 1.11) | 0.397 |

| Higher | 163 | 0.93 (0.78, 1.12) | 0.466 | 1.14 (0.90, 1.43) | 0.282 | 1.11 (0.83, 1.49) | 0.478 |

| Mother currently working | |||||||

| No | 1353 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 2603 | 1.17 (1.08, 1.28) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.24) | 0.055 | 1.28 (1.12, 1.47) | <0.001 |

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Urban | 1098 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Rural | 2858 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.07 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 0.924 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.11) | 0.51 |

| Religion | |||||||

| Catholic | 215 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Other Christian | 722 | 1.03 (0.86, 1.24) | 0.716 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.29) | 0.92 | 0.96 (0.69, 1.33) | 0.785 |

| Islam | 3009 | 1.29 (1.03, 1.61) | 0.026 | 1.28 (0.95, 1.74) | 0.11 | 1.81 (1.23, 2.67) | 0.003 |

| Traditionalist | 8 | 0.80 (0.22, 2.88) | 0.737 | 0.66 (0.09, 4.57) | 0.672 | 0.99 (0.14, 6.72) | 0.988 |

| Other | 2 | 0.85 (0.38, 1.93) | 0.7 | 1.81 (0.63, 5.19) | 0.272 | 1.22 (0.61, 2.41) | 0.574 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hausa | 1511 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Fulani | 675 | 0.71 (0.61, 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.67, 0.95) | 0.012 | 0.66 (0.53, 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Ekoi | 10 | 1.63 (0.93, 2.87) | 0.086 | 2.64 (1.35, 5.20) | 0.005 | 3.28 (1.45, 7.43) | 0.004 |

| Ibibio | 32 | 0.66 (0.38, 1.15) | 0.146 | 0.99 (0.51, 1.92) | 0.966 | 0.89 (0.38, 2.10) | 0.785 |

| Igala | 17 | 1.01 (0.64, 1.60) | 0.95 | 0.68 (0.43, 1.97) | 0.822 | 0.95 (0.40, 2.26) | 0.9 |

| Igbo | 276 | 1.23 (0.94, 1.62) | 0.134 | 0.92 (0.63, 1.55) | 0.973 | 1.14 (0.64, 2.04) | 0.647 |

| Ijaw/Izon | 19 | 1.42 (0.89, 2.28) | 0.143 | 2.39 (1.47, 3.87) | <0.001 | 2.75 (1.45, 5.23) | 0.002 |

| Kanuri/beriberi | 113 | 1.16 (0.94, 1.44) | 0.171 | 0.85 (0.59, 1.23) | 0.393 | 0.86 (0.60, 1.29) | 0.453 |

| Tiv | 68 | 1.07 (0.76, 1.51) | 0.702 | 1.09 (0.64,1.85) | 0.749 | 1.09 (0.56, 2.14) | 0.801 |

| Yoruba | 186 | 0.67 (0.51, 0.88) | 0.004 | 0.61 (0.42, 0.87) | 0.007 | 0.53 (0.34, 0.82) | 0.005 |

| Other | 1048 | 0.92 (0.80, 1.06) | 0.241 | 1.07 (0.89, 1.29) | 0.461 | 1.00 (0.80, 1.23) | 0.974 |

| Sources of drinking water | |||||||

| Unimproved | 1814 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Improved | 2142 | 1.30 (1.18, 1.41) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.11, 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.18, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| Sex of household head | |||||||

| Male | 3685 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Female | 271 | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) | 0.625 | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.214 | 0.91 (0.69, 1.17) | 0.449 |

| Wealth quintiles | |||||||

| Poorest | 1303 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Poorer | 1031 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | 0.859 | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) | 0.13 | 0.85 (0.72, 1.02) | 0.076 |

| Middle | 776 | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) | 0.076 | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | 0.013 | 1.10 (0.92, 1.34) | 0.285 |

| Richer | 552 | 1.18 (1.02, 1.37) | 0.026 | 1.39 (1.16, 1.66) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.98, 1.53) | 0.071 |

| Richest | 294 | 1.52 (1.28, 1.80) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.15, 1.79) | 0.002 | 1.41 (1.07, 1.85) | 0.015 |

| Region | |||||||

| North Central | 540 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Northeast | 554 | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) | 0.112 | 0.95 (0.78, 1.16) | 0.633 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.10) | 0.243 |

| Northwest | 1580 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 0.284 | 1.92 (1.55, 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.20, 1.99) | 0.001 |

| Southeast | 1234 | 0.88 (0.67, 1.16) | 0.367 | 1.11 (0.70, 1.78) | 0.648 | 1.23 (0.68, 2.24) | 0.492 |

| South | 232 | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) | 0.457 | 1.21 (0.84, 1.73) | 0.303 | 1.41 (0.89, 2.24) | 0.147 |

| Southwest | 162 | 1.34 (1.06, 1.69) | 0.016 | 1.53 (1.12, 2.12) | 0.008 | 1.66 (1.14, 2.43) | 0.009 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egbewale, B.E.; Karlsson, O.; Sudfeld, C.R. Childhood Diarrhea Prevalence and Uptake of Oral Rehydration Solution and Zinc Treatment in Nigeria. Children 2022, 9, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111722

Egbewale BE, Karlsson O, Sudfeld CR. Childhood Diarrhea Prevalence and Uptake of Oral Rehydration Solution and Zinc Treatment in Nigeria. Children. 2022; 9(11):1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111722

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgbewale, Bolaji Emmanuel, Omar Karlsson, and Christopher Robert Sudfeld. 2022. "Childhood Diarrhea Prevalence and Uptake of Oral Rehydration Solution and Zinc Treatment in Nigeria" Children 9, no. 11: 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111722

APA StyleEgbewale, B. E., Karlsson, O., & Sudfeld, C. R. (2022). Childhood Diarrhea Prevalence and Uptake of Oral Rehydration Solution and Zinc Treatment in Nigeria. Children, 9(11), 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111722