Development of Healthcare Service Design Concepts for NICU Parental Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

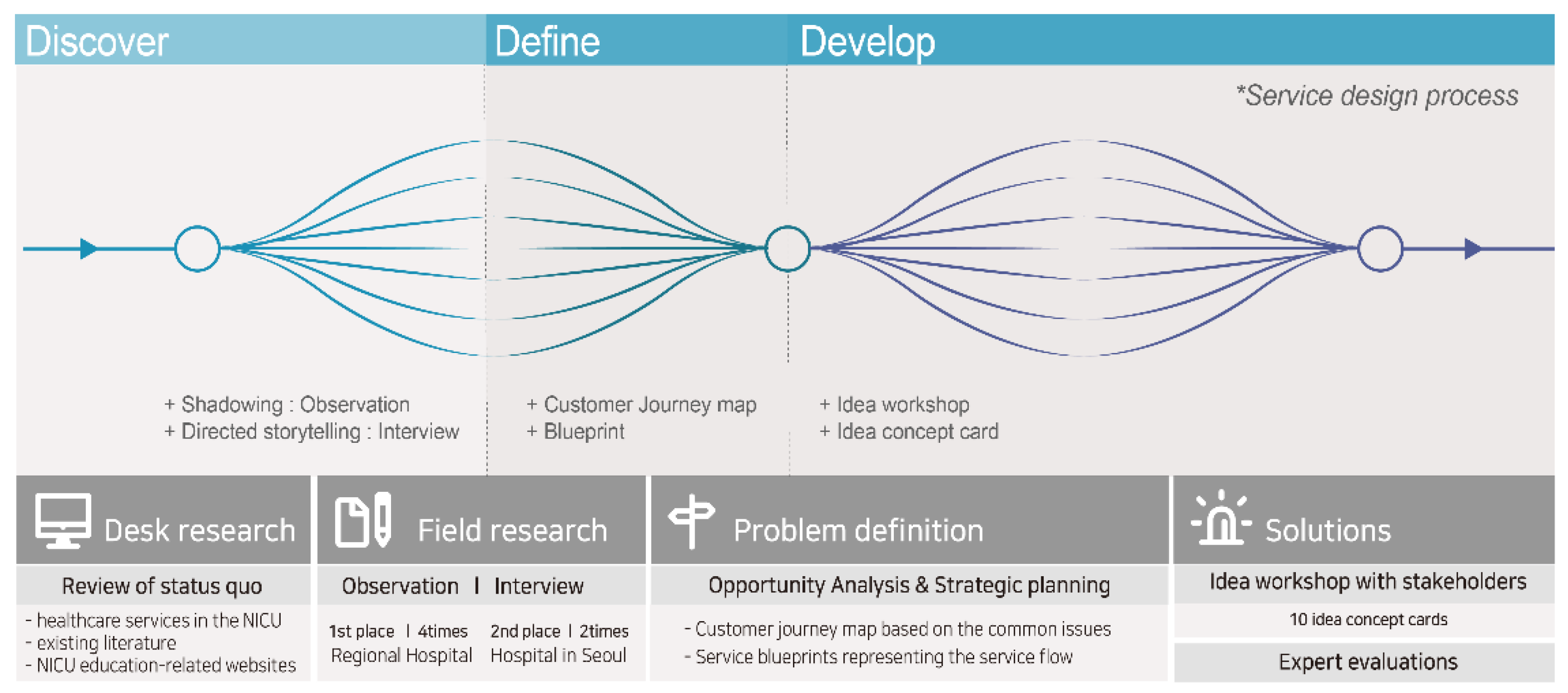

2. Methods

2.1. Discovery

2.1.1. Review of Status Quo (Existing Data)

2.1.2. Field Research

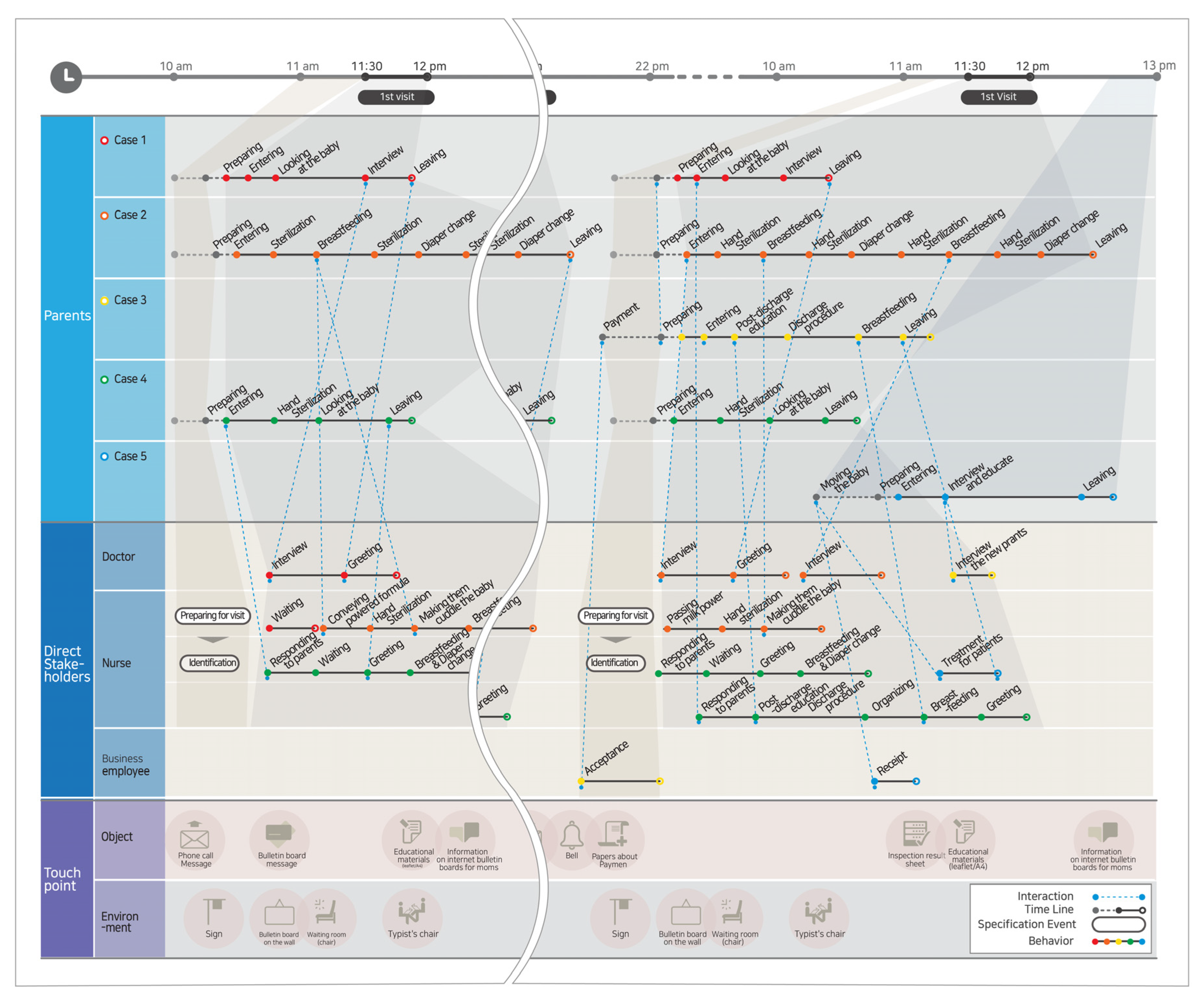

2.1.3. Observation

2.1.4. Interviews

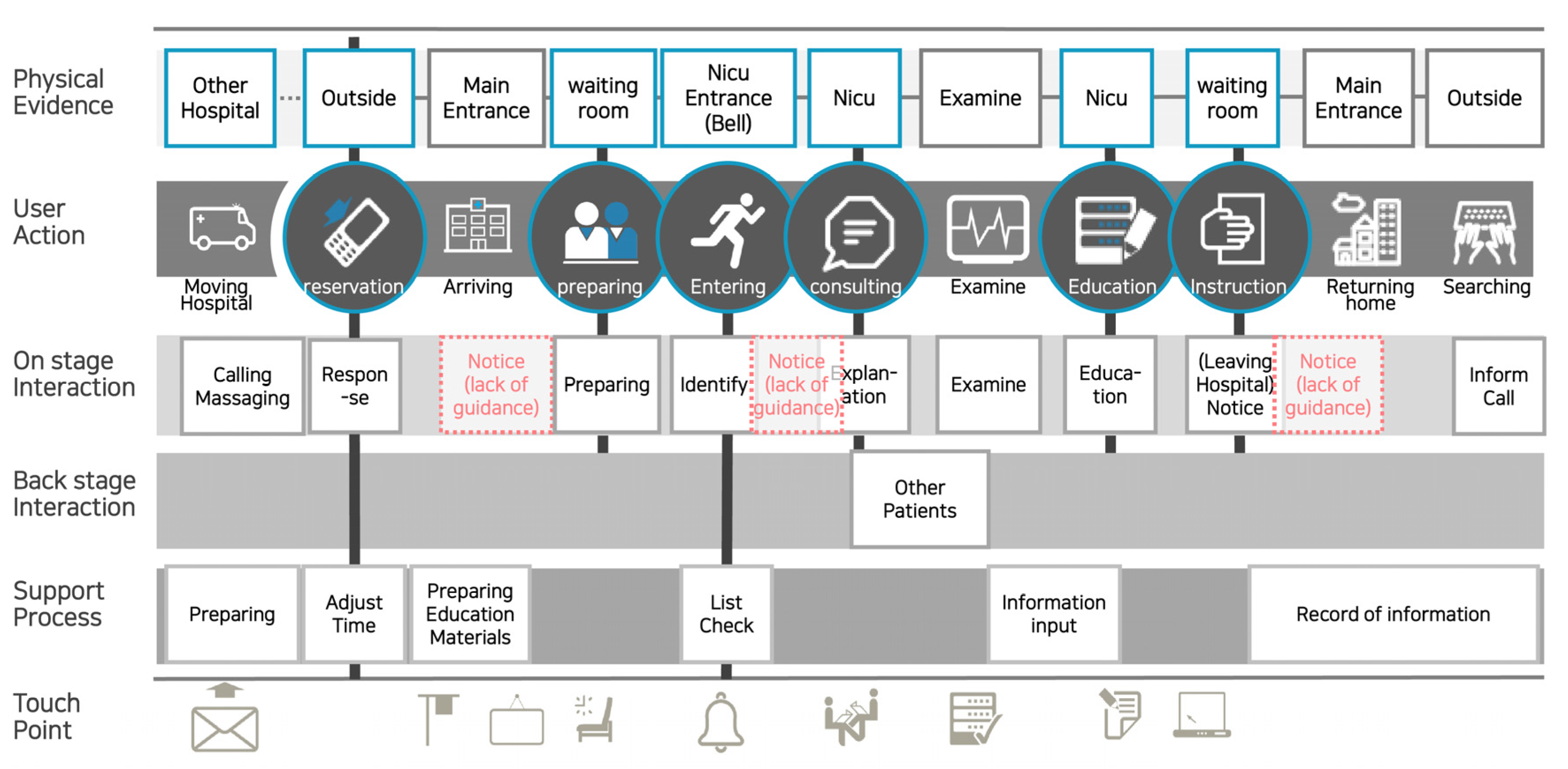

2.2. Definition

Opportunity Analysis and Strategy Planning

2.3. Development

2.3.1. Ideation

2.3.2. Service Concept

3. Results

3.1. Definition

3.2. Development

3.3. Validation of Design Strategy and Healthcare Service Design Concepts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, I.H. Construction a website for premature infant-based on the survey of previous homepages. J. Korean Acad. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2009, 15, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Axelin, A. Differences in parents’, nurses’ and physicians’ views of NICU parent support. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsironi, S.; Bovaretos, N.; Tsoumakas, K.; Giannakopoulou, M.; Matziou, V. Factors affecting parental satisfaction in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 18, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Foundation for the Care of Newborn Infants. Available online: https://www.efcni.org/health-topics/going-home/ (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Mosher, S.L. Comprehensive NICU Parental Education: Beyond Baby Basics. Neonatal Netw. 2017, 36, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusing, S.C.; Van Drew, C.M.; Brown, S.E. Instituting parent education practices in the neonatal intensive care unit: An administrative case report of practice evaluation and statewide action. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, M.; Oh, J. Integrative review on caring education papers for parents with a premature infant. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2013, 19, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Bang, K.S. Knowledge and needs of premature infant development and rearing for mothers with premature infants. Korean Parent-Child Health J. 2013, 16, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Giap, T.T.; Lee, M.; Jeong, H.; Jeong, M.; Go, Y. Patient-and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Mitchell, C.; Bowler, S. Patient-centered education: Applying learner-centered concepts to asthma education. J. Asthma 2007, 44, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, M.; Verma, R. Sequence effects in service bundles: Implications for service design and scheduling. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, X. The impact of service design and process management on clinical quality: An exploration of synergetic effects. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 36, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.Y.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, S.T.; Paik, J.K. A study on logo design for sensibility communication of HSD-centered for preference survey on hospital logo of domestic and foreign university hospital. J. Korean Soc. Des. Cul. 2013, 19, 414–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D.D. Service Marketing, 4th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, I.G.; Yu, H.N.; Choi, M.Y. A Study on the development of medical service design concept through the experience design research of rehabilitation patients—Focusing on the rehabilitation ward of public medical hospital B in Seoul. Des. Converg. Stud. 2016, 15, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Design Council. What Is the Framework for Innovation? Design Council’s Evolved Double Diamond. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/what-framework-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Shostack, L. Designing services that deliver. Harv. Bus Rev. 1984, 62, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Scupin, R. The KJ Method: A Technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology. Hum. Organ. 1997, 56, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykova, M.V. Transition from hospital to home in parents of preterm infants: A literature review. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 34, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemati, Z.; Namnabati, M.; Taleghani, F.; Sadeghnia, A. Mothers’ challenges after infants’ discharge from Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A qualitative study. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2017, 8, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Alderdice, F.; Gargan, P.; McCall, E.; Franck, L. Online information for parents caring for their premature baby at home: A focus group study and systematic web search. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pepper, D.; Rempel, G.; Austin, W.; Ceci, C.; Hendson, L. More than information: A qualitative study of parents’ perspectives on neonatal intensive care at the extremes of prematurity. Adv. Neonatal Care 2012, 12, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Robson, K.; Bracht, M.; Cruz, M.; Lui, K.; Alvaro, R.; da Silva, O.; Monterrosa, L.; Narvey, M.; Ng, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Family Integrated Care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: A multicentre, multinational, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Spittle, A.; Anderson, P.J.; O’Brien, K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adama, E.A.; Adua, E.; Bayes, S.; Mörelius, E. Support needs of parents in neonatal intensive care unit: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfannstiel, M.A.; Rasche, C. Service Design and Service Thinking in Healthcare and Hospital Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Customer Issues | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parents | Situation | Increased fatigue and anxiety of the mother. Always feeling vulnerable, despite being the customer. Difficulties in understanding professional medical terms and in identifying the baby’s conditions. |

| Interpretation | Increased anxiety and sensitivity in the postnatal period. Being sensitive to the nurses because the baby is in the nurse’s care. Collecting information from the internet and specialty literature to address their unresolved questions. | |

| Service Provider Characteristics | ||

| Doctors | Situation | Clear and objective explanations are required. Parents’ interviews are conducted only on request. Necessary to persuade parents to allow their babies to receive treatment. |

| Interpretation | Realistic explanations are more important than vague expectations. Strong support from the parents but lack of opportunities to meet with specialists. Important to build trust. | |

| Dedicated education nurse | Situation | Having numerous private questions after the discharge of the baby. Handover of information related to sensitive parents. |

| Interpretation | Repetition of basic questions from parents. Requires a manual to assist parents. | |

| General nurse | Situation | Parental education takes place for a limited period of time. Frequent nurse rotation due to shift work. Difficulties facing fatigued parents. |

| Interpretation | All education must be completed within the visiting hours. Poor educational efficiency due to frequent nurse changes. Emotional difficulty in dealing with parents. | |

| Issues |

|---|

| 1. Lack of understanding and consideration for parents 2. Physical limitations, including facilities and environment 3. Operating systems that hinder work efficiency 4. Psychological burdens in a desolate atmosphere 5. Lack of systematic protocols for education 6. Lack of medical information7. Confusion regarding unforeseen situations |

| 1. Improving the Design of Educational Materials | |

| Unified design (size, format) for ease of understanding and storage. Provide visualized data for content that requires visual understanding (text, image, or video). Provide workbooks for content that requires exact measurement such as breastfeeding and medication management. | |

| Problem | Difficult to manage educational materials as they have different sizes and formats. Effective teaching methods differ according to the content of the education. |

| Tangible action | Increase the level of understanding by unifying the design. Use effective information delivery methods for different educational content (text/image/video). Important and frequently viewed content to be provided as posters, rather than booklets, to be posted on walls. |

| Limitations | None |

| 2. Improving Guidance Materials for the Care of High-Risk Infants | |

| Provide guidelines on caring for high-risk infants after discharge, depending on corrected age. Provide self-check material so that the parents can assess the situation themselves. Provide guidance on changes and accompanying methods of change throughout growth and development, such as changes to general milk powder and breastfeeding amounts. Provide Q&A for emergency and manageable situations. | |

| Problem | High volume of everyday guidance due to changes in growth and development. Difficult to check the specifics of growth and development of the baby. There are not as many emergencies as inquiries relating to abnormal symptoms displayed by babies. |

| Tangible action | In addition to examinations of infants and toddlers, distribute material on growth and development, allowing for constant self-checking. Provide a recording platform on the website, to allow for its use as reference data during outpatient visits. |

| Limitation | Using websites to record inquiries requires an electronic records management system linked with medical treatment. |

| 3. Practicum Kit | |

| Educational kits to be placed inside and outside the NICU, which may be used while waiting during visiting hours. Parents will use them directly and ask questions, allowing them to obtain practical knowledge. Kit contents are systematically constructed to ensure easy content acquisition and utilization. | |

| Problem | As education is provided verbally as a one-time event, on paper and via video, it is difficult to accurately understand it and put it into practice. Queries occur in the process of childrearing after discharge. |

| Tangible action | Place items used in childrearing out during visiting hours so that the parents are free to utilize them. Practice activities, such as medicine dosage. The overall image of the education can be conveyed using the items inside the kit. |

| Limitation | Sufficient use of the kit is impossible as visiting hours are short. Costs associated with developing and making the kits available. |

| 4. Parent Proficiency Checklist | |

| Create a list of contents for education, enter the names of educators and parents to establish accountability. Allow for the baby’s discharge after the parents are fully proficient in the educational content, move to the next stage, or repeat the education depending on the proficiency of the parents. Checklist to be provided to both the hospital and the parents; special education to be mandatory for both parents. | |

| Problem | Depending on the difference in the skills of education providers and consumers, discharges may happen without the educational content having been fully understood. Parents are unaware of the education they have, or have not, received. Parents are not aware of the type of education they require. Parents have received CPR education but feel that they would not be able to do it in emergencies. |

| Tangible action | Create a mandatory education list for each parent and check off its points as education is provided. Confirm the level of understanding with parents, repeating education when necessary. Adjust the discharge schedule depending on the level of education absorbed. |

| Limitation | Visiting hours are limited and multiple parents must be educated. Additional personnel may be required to systematically manage and deliver education. Given individual differences in acquisition of knowledge and poor participation, discharges may be delayed. |

| 5. Systematic Parental Education Manual | |

| Organize the education manual for effective parental education. Include parental communication and response guides on the content of the education, number of educational programs provided, targets of mandatory education, evaluation of learning ability, communication methods, and speaking styles. Make notes on customized information (characteristics, tendencies, and habits of the baby) and guide the parents through these during education, to increase credibility. | |

| Problem | Each healthcare provider renders different information during visits, leading to confusion. Nurses change often, leading to repeated or omitted information. Some parents are hurt by the tone of voice used by healthcare providers. Nurses have difficulties in dealing with parents. |

| Tangible action | Unify basic education and coping manuals for parents’ questions and use them when communicating with parents. Through the education manual, parents can obtain consistent information, and nurses can appropriately respond to difficult situations with parents. |

| Limitation | Heavier workload for nurses as they must understand the manual. The manuals cannot be used to respond to unexpected situations. |

| 6. Predictable Guidelines for Testing and Treatment Plans | |

| Provide visualized overall plans on testing and treatment for the parents. Include information, side effects, and results of treatments and tests accordingly. | |

| Problem | Parents are always anxious as they are not able to predict the situations that may arise in the coming steps. Lack of information on the treatment and testing underway makes searches difficult as parents do not know what they are searching for. |

| Tangible action | Common testing and treatment plans to be provided for typical cases of high-risk infants, allowing the parents to be aware of and prepare for important information. |

| Limitation | Difficult to apply specific cases for each baby. Risk of increasing confusion for parents if the situation differs from the plan. |

| 7. Waiting Time that Provides Comfort | |

| Use affordance design to allow the parents—even those visiting for the first time—to adapt to the situation easily. Place comforting phrases in different places to create a warm environment, helping the parents to feel comforted. Use a text-based, interactive medium (for example, a question board) so that the parents are free to ask questions and receive answers from the healthcare provider as they wait. Adjust visiting hours if delivery rooms and the NICU are attached to one another in the hospital. | |

| Problem | Parents of high-risk infants are likely to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, guilt, despair, and depression. The waiting area is small and the movements of parents are limited. Feeling uncomfortable as other people stare at them while they wait. Notices filled with medical terms create a fearful atmosphere. |

| Tangible action | Organize flow of movement through affordance design. Adjust visiting hours if delivery rooms and the NICU are attached to one another, reducing emotional burden for the parents. Use warm and sympathetic phrases to comfort and cheer fatigued parents. Create a question board to provide a participatory platform where parents can ask questions and receive answers. Parents can share common questions and answers, resolving the issue of unnecessary repetitions. |

| Limitation | Expenditure associated with creating a comfortable environment. May be difficult to implement given the spatial conditions in the hospital. |

| 8. Message Cards that Convey Feelings | |

| Give cards to parents so that they can write to the healthcare provider and communicate with them freely. Attach general information on topics such as baby’s body weight and feeding records to the bed so that the parents can freely check it during visits. | |

| Problem | Parents have trouble communicating as they feel the healthcare provider is too busy. Wanting to check daily records of the baby, such as weight, temperature, and feeding volume, even if they do not know much about the information. |

| Tangible action | Message cards can act as touchpoints with the healthcare providers who are hard to meet with, such as head nurses or specialists. The parents can be comforted in the process of honestly laying out words that can be difficult to convey directly, which can reduce unnecessary conversations and waste of emotions. |

| Limitation | Possible increase in the burden on healthcare providers due to the message cards. |

| 9. Reservation System for Visits | |

| Develop a simple visit scheduling system in consideration of the positions of both nurses and parents. | |

| Problem | Depending on the situation, it is possible that parents may misunderstand the nurses asking about their visits. Nurses need to be aware of the number of visitors to prepare for their work allocation and responses to parents. Parents need to go through nurses to apply for appointments. |

| Tangible action | Easier application process for appointments through a simple online system, rather than phone calls that can be misleading. Nurses can determine the number of visitors, and parents can check for the number of visitors and change visiting hours. Parents can apply for appointments with specialists in a simple manner. |

| Limitation | Issues associated with development and maintenance costs. |

| 10. Platform for Post-Discharge Information Sharing | |

| Create a Q&A section that parents can use to easily ask questions after discharge. Create a platform for parents of discharged babies, allowing them to exchange information with each other. Provide emergency contact guides. | |

| Problem | Increased workload for nurses due to big and small inquiries from parents. After discharge, parents face real-life childrearing challenges and develop numerous questions. They access experience-based, incorrect information from the internet and respond based on such information. |

| Tangible action | Post a Q&A section on frequently asked questions. Create an internal community to facilitate information exchange among parents. Expert responses promote reliability and a reduced workload for nurses. |

| Limitation | Difficulties in ongoing operations and management. Requires real-time responses. May face the risk of becoming a general online community. |

| Healthcare Service Design Concept | Mean | Overall Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Improving the design of educational materials. | 5.88 | 5.60 |

| 2. Improving guidance materials for caring for high-risk infants. | 5.81 | |

| 3. Practicum kit. | 5.85 | |

| 4. Parent proficiency checklist. | 5.92 | |

| 5. Systematic parental education manual. | 5.57 | |

| 6. Predictable guidelines for testing and treatment plans. | 5.69 | |

| 7. Waiting time that provides comfort. | 5.52 | |

| 8. Message cards that convey feelings. | 5.33 | |

| 9. Reservation system for visits. | 5.21 | |

| 10. Post-discharge information sharing platform. | 5.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, H.; Woo, D.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, M.; Kim, D.H. Development of Healthcare Service Design Concepts for NICU Parental Education. Children 2021, 8, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090795

Yu H, Woo D, Kim HJ, Choi M, Kim DH. Development of Healthcare Service Design Concepts for NICU Parental Education. Children. 2021; 8(9):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090795

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Hanui, Dahae Woo, Hyo Jin Kim, Minyoung Choi, and Dong Hee Kim. 2021. "Development of Healthcare Service Design Concepts for NICU Parental Education" Children 8, no. 9: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090795

APA StyleYu, H., Woo, D., Kim, H. J., Choi, M., & Kim, D. H. (2021). Development of Healthcare Service Design Concepts for NICU Parental Education. Children, 8(9), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090795