1. Introduction

Play is ubiquitous in childhood and is recognised by the United Nations Convention as a fundamental right of all children [

1]. Importantly, as well as bringing feelings of happiness and joy, play has been associated with myriad benefits for children. In relation to physical health, play has been associated with increased physical activity [

2,

3,

4], decreased sedentary behaviour [

5,

6], improvements in cardiovascular fitness [

6,

7], and reduced risk for childhood obesity [

6,

8]. Further, play supports the development of children’s physical abilities and is positively associated with their fundamental movement skills [

9,

10]. Play is also essential for children’s socioemotional health. Through play, children learn to share, negotiate, resolve conflicts, regulate their emotions, and control their impulses [

11]. Cognitively, play supports children’s ability to make decisions and problem solve [

12] and is associated with both learning behaviours and learning readiness [

11,

13,

14].

Adventurous, or risky, play has been defined as exciting, thrilling play where the child experiences a level of fear and is able to take age-appropriate risks [

15,

16]. Sandseter [

3] identified six categories of risky play; play at great heights, play at high speed, play with dangerous tools, play near dangerous elements, rough and tumble play, and play where children can disappear/get lost. Children appear to enjoy playing in this way [

17] and feel strongly about being afforded opportunities to assess risk for themselves [

18]. Despite this, there is evidence that children’s opportunities for, and engagement in, adventurous play has declined in recent decades. Children play outside less than in previous generations [

19], have less independent mobility [

20] and are not allowed out alone until they are almost two years older than their parents were [

21]. These declines have often been attributed to increased societal concerns surrounding children’s safety [

22]. Dodd and Lester’s [

15] conceptual model of adventurous play and anxiety highlights the critical role of the social environment in facilitating adventurous play. Specifically, the authors argue that the nature of adult supervision and rules and policies constrain children’s opportunities to take risks in their play [

15]. These factors are likely to play a role in children’s adventurous play both in and out of the school context. Adults, as such, represent an important constraint on children’s opportunities to take risks and challenges in their play [

23,

24]. Indeed, it is known that parents’ attitudes and beliefs about risk during play are associated with the amount of time children spend playing in an adventurous way [

21].

There are concerns for what this decline in adventurous play may mean for children’s health broadly, and in particular for their mental health. Specifically, Gray [

11] argues that that the decline of children’s play may be a contributing factor to the rise of mental health problems in children and adolescents [

25]. Alongside this, there are concerns that a culture of risk aversion may limit children’s risk taking and, in doing so, deny them the opportunity to learn from these experiences, affecting their ability to effectively judge risk in adolescence and into adulthood [

26]. Indeed, it has been proposed that children’s engagement in age-appropriate risk through adventurous play may provide an adaptive means by which children can learn about fear, uncertainty, risk judgement, and coping. This learning may act as a protective factor for children in later life when they are faced with situations that provoke fear or uncertainty [

15].

Whilst theoretical work on adventurous play is in its infancy, there is a growing body of empirical research demonstrating that adventurous play may be beneficial for other aspects of children’s health. For example, a systematic review conducted in 2015 examined the relationship between risky outdoor play and a range of health outcomes [

27]. The authors concluded that environments that supported risky play had a range of benefits for children’s health, behaviour and development, including increased physical activity, decreased sedentary behaviour, improvements in social interactions and reported improvements in creativity and resilience in children. Although there are understandable concerns about child injuries, unstructured play, defined as play that is spontaneous, self-directed, intrinsically motivated and with an absence of external rewards [

11,

28], is relatively low risk (0.15–0.17) when compared to the incidence rates of injury per 1000 h for sports (0.20–0.67) and active transportation (0.15–0.52) [

29]. The outcomes of the 2015 review informed the publication of an international position statement on outdoor active play in children aged 3–12 years [

30]. This states that “Access to active play in nature and outdoors—with its risks—is essential for healthy child development.” [

30] (p. 1).

A number of school-based interventions focussed on increasing children’s opportunities for adventurous, or risky, play during recess or breaktimes have been designed and some have been evaluated. In several instances, these have consisted of introducing loose parts into the play space [

31,

32]. Loose parts are materials with no fixed purpose (e.g., a tyre, boxes) and have been found to afford children the opportunity to take risks in their play [

33]. The Sydney Playground Project focussed on the introduction of recycled materials into school playgrounds and included a risk-reframing workshop for parents and teachers [

31]. In the UK, Outdoor Play and Learning (OPAL) provide support to help schools improve play during breaktimes, which includes addressing barriers around risk aversion [

34]. Further, in New Zealand, the PLAY study focussed on increasing opportunities for risk and challenge, reducing rules, and adding loose parts [

32]. Where these programmes have been evaluated, findings show that increasing children’s opportunities for adventurous play increases children’s physical activity [

35]; although not consistently across studies [

36], decreases disruptive behaviour and benefits children’s learning and social development [

34], increases creativity and resilience [

35], and improves children’s happiness at school [

32]. Thus, adventurous play may be beneficial for various facets of children’s health.

Although there is initial evidence for positive effects of play-based interventions, with a risky play component, the extent to which they build upon evidence regarding what needs to be targeted to increase opportunities for, and engagement in adventurous play in schools is unclear. It is therefore essential to understand the barriers and facilitators that schools face in providing opportunities for (i.e., to afford the environment for adventurous play) and allowing engagement in (i.e., to provide permission to engage in) adventurous play, in order to design optimal and effective interventions. Our aim in this review is therefore to bring together findings from qualitative research providing insights into the perceived barriers and facilitators of adventurous play in schools. To analyse the findings yielded via a systematic search, two review methodologies were used. Papers that met a pre-specified quality threshold were analysed via meta-aggregative synthesis and papers that met our inclusion criteria but did not meet the quality criteria were analysed via narrative synthesis. The results of each will be presented separately and brought together in the discussion.

4. Discussion

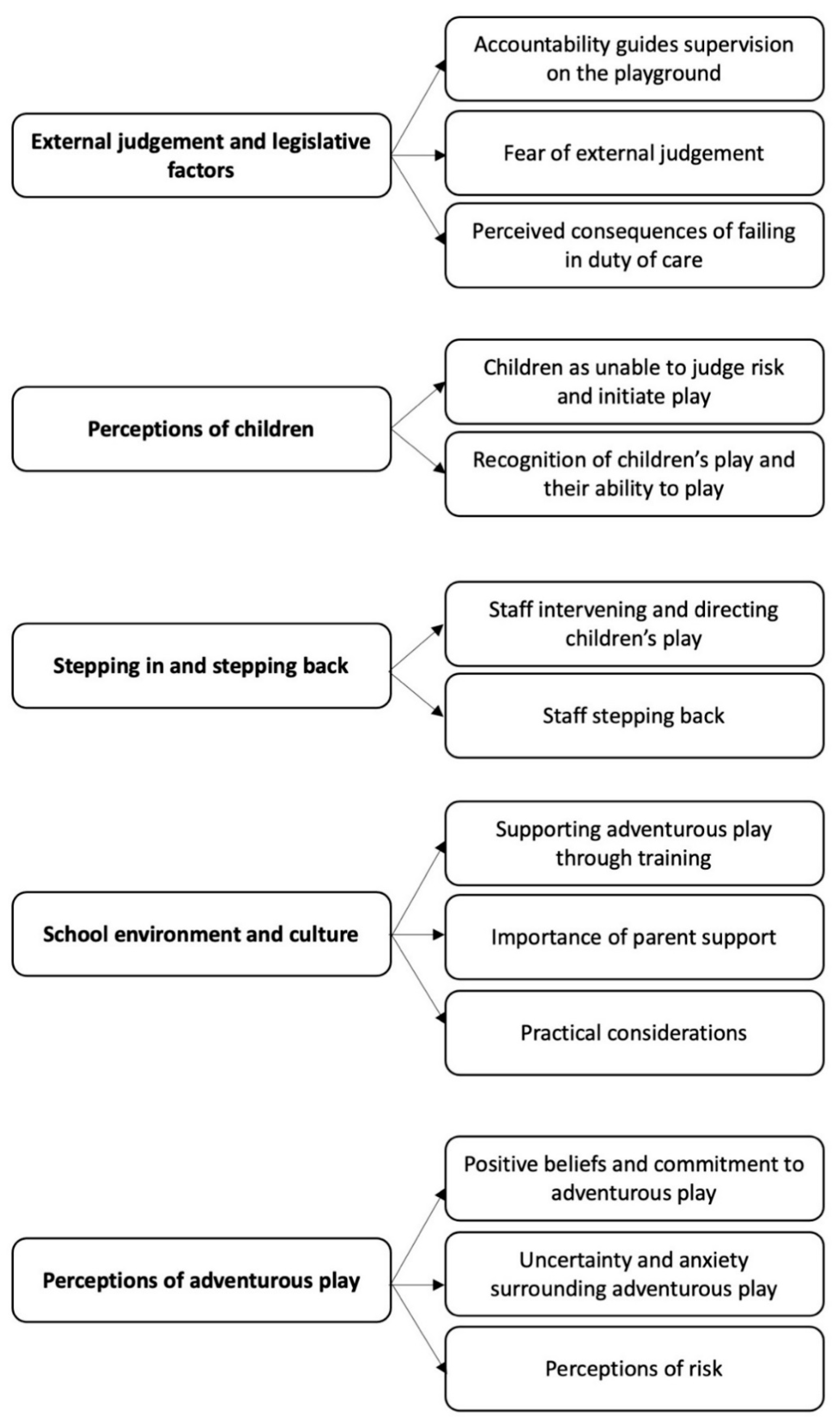

This review aimed to provide insights into the perceived barriers and facilitators of adventurous play in schools by bringing together findings from existing qualitative research. We conducted a meta-aggregative synthesis and a narrative synthesis of findings across nine studies. Below, we bring together these findings, reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of the existing literature, and make specific recommendations for policy and practice.

4.1. What Are the Perceived Barriers and Faciliatators of Adventurous Play in Schools?

There was considerable consistency between the results of the meta-aggregative synthesis and the narrative synthesis. From a psychological perspective, adults’ perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about play and about children’s abilities were clearly present in both analyses. Focusing first on adults’ attitudes and beliefs about adventurous play, it was clear across studies that adults often held positive beliefs about the benefits of adventurous play for children, which motivated them to support its provision. However, these attitudes and beliefs existed against a backdrop of uncertainty, which provoked anxiety in supervising children and causing them to intervene in a limiting way. The role of individual differences in perceptions of risk and tolerance of uncertainty was also clear.

Other commonly held perceptions included perceiving children as unable to judge risk and initiate play for themselves, although there were contrasting views about how well children are able to do this independently. There were examples of participants who were able to identify a change in their expectations as they gave children more space to play and recognised that their assumptions were incorrect. This happened when adults consciously decided to step back from children’s play. In doing so, they were able to recognise children’s abilities, thus giving them confidence to step back further [

43].

Additionally, consistent between the two analyses was the importance of a whole-school approach to adventurous play, which included parents and school caretakers. Several studies highlighted staff concern about parent reactions, especially if a child could be injured playing adventurously at school. Individual differences in how parents responded to adventurous play opportunities was evident; whilst for some parents this appeared to increase the appeal of the school, in some cases parents chose to remove their child from the school as a result of their approach to play [

32]. This contrasting finding highlights the varied perceptions of parents and the challenges schools face in providing opportunities for adventurous play in school. Given this, risk-reframing sessions, which help parents to understand the motivations for this approach to play, are likely to be important. Staff in schools providing this type of risk-reframing session explained that parents attending the sessions gained a mutual understanding that mitigated fears. Achieving this whole-school approach was not straightforward however, with a headteacher in one study describing it as “the hardest challenge” and a school leader in another study reporting that it could be difficult to change the attitudes of caretakers and teachers. Strong leadership and a shared goal appeared to help overcome some of these challenges, as did training and education around adventurous play for all members of the school community. Indeed, Farmer et al.’s [

32] study highlights that, without this training, schools may have little knowledge and understanding about how their rules and practices affect children’s play.

In addition to the above, Health and Safety and concerns about legislation were also discussed as barriers. Across several studies, staff mentioned their duty of care as being a barrier to allowing children to take risks when they play. Staff were also concerned about the consequences if things went wrong, including external judgement via outside agencies such as school inspectors or potentially losing their jobs.

4.2. Study Reflections and Limitations

The final synthesis consisted of a small number of studies; of the nine studies included in the review, only four met our quality criteria for inclusion in the meta-aggregative synthesis. The primary reason for exclusion of the other papers was that the influence of the researchers on the research (and vice versa) was not clearly acknowledged. This is not to say that these studies were not conducted to a high standard, nor that the results are not informative; rather, what was reported in the available versions of the articles did not allow us to be sure that the quality was high enough for the result to be included in the formal analysis. The overall methodological quality of the articles should be kept in mind when considering the recommendations for policy and practice made below.

We chose to focus the review on qualitative research because this approach provides rich data. This richness allows for a deeper understanding of the issues relevant to the research questions, thus enabling us to make clearer, more specific recommendations for policy and intervention. Although the lack of quantitative data may be considered by some to be a limitation, this depth of understanding is difficult to obtain from quantitative data.

It is noteworthy that several of the studies included within the review focussed specifically on children with disabilities [

42,

43]. It is plausible that some unique barriers and facilitators of adventurous play may exist for children with disabilities; however, due to the small number of studies identified, a sub-analysis was not possible and we are unable to make recommendations that are specific to children with disabilities. Despite this, many of the findings from the studies that focussed on children with disabilities were represented within core themes that were present across studies. As a result, the recommendations are likely to apply to children with disabilities as well as typically developing children.

A potential limitation is that six of the nine studies included in the review reported data collected as part of an intervention evaluation. The barriers and facilitators identified within the review may therefore more closely reflect experiences of participating in an intervention related to adventurous play. It is plausible that the barriers and facilitators identified outside of an intervention context may differ. Nevertheless, the studies give valuable insights into the mechanisms likely to be involved in supporting and facilitating adventurous play in schools and the barriers that exist for implementing and changing attitudes towards adventurous play in schools. Similarly, the findings are only relevant to school contexts, which aligns with our aims. It is likely that other barriers and facilitators of adventurous play exist within a broader social context. Specific barriers and facilitators may also differ across different countries and cultures; the articles included within this review were primarily from Western countries. Future research would benefit from examining barriers and facilitators of adventurous play across cultures and geographical locations.

4.3. Implications for Research

The review and the findings indicate several directions for future research. As aforementioned, six of the nine studies included within the review report data from intervention studies. This suggests that to date, there is relatively little empirical work qualitatively examining the barriers and facilitators of adventurous play in school-aged children that exists to inform interventions. Future work is therefore needed to examine barriers and facilitators of adventurous play outside the context of an intervention. Of the three of the studies included that specifically examined the barriers to and facilitators of adventurous play in schools, outside an intervention context [

40,

44,

45], participants were primarily school professionals, including headteachers and teachers. Given the importance of a whole-school approach within the review findings, it is recommended that research about adventurous play in schools should also include parents, lunchtime supervisors, and the wider school community (e.g., caretakers). Indeed, whilst the necessity for parent support for adventurous play was evident across analyses, the voice of parents pertaining to the barriers and facilitators for adventurous play in schools was absent. Research with the wider school community is critical to gain a wider understanding of the perceived barriers and facilitators of adventurous play in schools.

4.4. Recommendations for Policy and Practice

On the basis of our analyses, we make the following recommendations for policy and for practice, specifically in relation to future interventions.

4.4.1. Policy

Regulatory bodies including school inspectors and Health and Safety executives must provide clear guidance regarding risk–benefit analysis and the provision of adventurous play in schools.

Funding should be provided to ensure that schools have the resources to ensure children’s play is adequately provided for.

4.4.2. Practice

Interventions must require a whole-school approach, with parents and school staff, including lunchtime supervisors, teachers, and caretakers/cleaners involved and informed.

Training and education around adventurous play is vital. Specifically, training must:

- 1.1.

Address fears and uncertainty surrounding staff member and school accountability in relation to duty of care and the potential for child injury. This can be gained via clear guidance from regulatory bodies as well as through training.

- 1.2.

Include training regarding children’s skills and capabilities to play, including children’s ability to judge risk for themselves.

- 1.3.

Include education around how intervening in children’s play and directing through language may limit children’s adventurous play engagement.

- 1.4.

Focus on developing positive beliefs about adventurous play, including understanding the benefits of adventurous play.

- 1.5.

Include support in how to recognise and evaluate risk and hazards.

School staff should be supported to reflect on how their current rules and practices might have a positive and negative impact on children’s play, including what staff do to manage their own uncertainty.

Interventions should include some supported practical exercises to carry out which require staff to experiment with stepping back from children’s play and observing what happens. This action of stepping back should facilitate children’s play and provide an opportunity for adults to adjust their perceptions about children’s abilities. Stepping back facilitated children’s ability to play and, therefore, this should be a key message in intervention and training.

Interventions must recognise the practical considerations that may arise, such as time and appropriate space, and support schools to overcome these potential barriers.