First Aid Practices and Health-Seeking Behaviors of Caregivers for Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Ujjain, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site, Study Population, and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection Tools and Methods

2.3. Definitions

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Child and Adolescent Health Collaboration; Kassebaum, N.; Kyu, H.H.; Zoeckler, L.; Olsen, H.E.; Thomas, K.; Pinho, C.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Dandona, L.; Ferrari, A.; et al. Child and adolescent health from 1990 to 2015: Findings from the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors 2015 study. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 573–592. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Child Injury Prevention. 2008. Available online: http://www.Who.Int/violence_injury_prevention/child/injury/world_report/en/ (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Wesson, H.K.; Boikhutso, N.; Bachani, A.M.; Hofman, K.J.; Hyder, A.A. The cost of injury and trauma care in low- and middle-income countries: A review of economic evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 29, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, S.N. The problem of children’s injuries in low-income countries: A review. Health Policy Plan. 2002, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonge, O.; Hyder, A.A. Reducing the global burden of childhood unintentional injuries. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Escobar, F.J.; Gutierrez, M.I. Injuries are not accidents: Towards a culture of prevention. Colomb. Med. 2014, 45, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, A.M.; Giannakopoulos, G.F.; Moerbeek, P.R.; Jansma, E.P.; Bonjer, H.J.; Bloemers, F.W. The influence of prehospital time on trauma patients outcome: A systematic review. Injury 2015, 46, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, D.M.E.; Islam, M.I.; Sharmin Salam, S.; Rahman, Q.S.; Agrawal, P.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, F.; El-Arifeen, S.; Hyder, A.A.; Alonge, O. Impact of first aid on treatment outcomes for non-fatal injuries in rural bangladesh: Findings from an injury and demographic census. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadeyibi, I.O.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Mustafa, I.A.; Ugburo, A.O.; Adejumo, A.O.; Buari, A. Practice of first aid in burn related injuries in a developing country. Burns 2015, 41, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldsetzer, P.; Williams, T.C.; Kirolos, A.; Mitchell, S.; Ratcliffe, L.A.; Kohli-Lynch, M.K.; Bischoff, E.J.; Cameron, S.; Campbell, H. The recognition of and care seeking behaviour for childhood illness in developing countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Devkota, S.; Ranjit, A.; Swaroop, M.; Kushner, A.L.; Nwomeh, B.C.; Victorino, G.P. Fall injuries in Nepal: A countrywide population-based survey. Ann. Glob. Health 2015, 81, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyedu, A.; Mock, C.; Nakua, E.; Otupiri, E.; Donkor, P.; Ebel, B.E. Pediatric first aid practices in Ghana: A population-based survey. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkheijm, A.; Zuidgeest, J.J.; van Dijk, M.; van As, A.B. Childhood unintentional injuries: Supervision and first aid provided. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2013, 10, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashreky, S.R.; Rahman, A.; Chowdhury, S.M.; Svanstrom, L.; Linnan, M.; Shafinaz, S.; Khan, T.F.; Rahman, F. Perceptions of rural people about childhood burns and their prevention: A basis for developing a childhood burn prevention programme in Bangladesh. Public Health 2009, 123, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdzan, S.N.; Liew, S.M.; Khoo, E.M. Unintentional injury and its prevention in infant: Knowledge and self-reported practices of main caregivers. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuosi, A.A.; Adzei, F.A.; Anarfi, J.; Badasu, D.M.; Atobrah, D.; Yawson, A. Investigating parents/caregivers financial burden of care for children with non-communicable diseases in Ghana. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirongoma, F.; Chengetanai, S.; Tadyanemhandu, C. First aid practices, beliefs, and sources of information among caregivers regarding paediatric burn injuries in Harare, Zimbabwe: A cross-sectional study. Malawi Med. J. 2017, 29, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomar, M.; Rouqi, F.A.; Eldali, A. Knowledge, attitude, and belief regarding burn first aid among caregivers attending pediatric emergency medicine departments. Burns 2016, 42, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, S.G.; Burahee, A.; Albertyn, R.; Makahabane, J.; Rode, H. Parent knowledge on paediatric burn prevention related to the home environment. Burns 2016, 42, 1854–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, P.F.; Helmkamp, J.C.; Williams, J.M.; Haque, A.; Furbee, P.M. Matched analysis of parent’s and children’s attitudes and practices towards motor vehicle and bicycle safety: An important information gap. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2004, 11, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, H.E.; Bache, S.E.; Muthayya, P.; Baker, J.; Ralston, D.R. Are parents in the UK equipped to provide adequate burns first aid? Burns 2012, 38, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, L.A.; Barr, M.L.; Poulos, R.G.; Finch, C.F.; Sherker, S.; Harvey, J.G. A population-based survey of knowledge of first aid for burns in New South Wales. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 195, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Jiang, F.; Jin, X.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, X. Pediatric first aid knowledge and attitudes among staff in the preschools of Shanghai, China. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, A.J.; Gulla, J.; Thode, H.C., Jr.; Cronin, K.A. Pediatric first aid knowledge among parents. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2004, 20, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.C.; Fernandes, M.N.; Sa, M.C.; Mota de Souza, L.; Gordon, A.S.; Costa, A.C.; Silva de Araujo, T.; Carvalho, Q.G.; Maia, C.C.; Machado, A.L.; et al. The effect of educational intervention regarding the knowledge of mothers on prevention of accidents in childhood. Open Nurs. J. 2016, 10, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, A.; Mehra, L.; Diwan, V.; Pathak, A. Unintentional childhood injuries in urban and rural Ujjain, India: A community-based survey. Children 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Census of India. District Profile-Ujjain. 2011. Available online: http://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/302-ujjain.html (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4, 2015-16. District Fact Sheet, Ujjain, Madya Pradesh. 2016, p. 6. Available online: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/FCTS/MP/MP_FactSheet_435_Ujjain.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Fochsen, G.; Deshpande, K.; Diwan, V.; Mishra, A.; Diwan, V.K.; Thorson, A. Health care seeking among individuals with cough and tuberculosis: A population-based study from rural India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2006, 10, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Conducting Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. 2004. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42975/1/9241546484.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Maneesriwongul, W.; Dixon, J.K. Instrument translation process: A methods review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Training Educating and Advancing Collaboration in Health on Violence and Injury Prevention; Users’ Manual; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: Whqlibdoc.Who.Int/publications/2012/9789241503464_eng.Pdf?Ua=1 (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Sharma, M.; Brandler, E.S. Emergency medical services in India: The present and future. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2014, 29, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannvik, T.D.; Bakke, H.K.; Wisborg, T. A systematic literature review on first aid provided by laypeople to trauma victims. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2012, 56, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Ingram, M.; Lofthouse, H.K.; Montagu, D. What is the role of informal healthcare providers in developing countries? A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, K.R.; Diwan, V.; Lönnroth, K.; Mahadik, V.K.; Chandorkar, R.K. Spatial pattern of private health care provision in Ujjain, India: A provider survey processed and analysed with a geographical information system. Health Policy 2004, 68, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.S.; Chang, H.; Shyu, K.G.; Liu, C.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Hung, C.R.; Chen, P.H. A method to reduce response times in prehospital care: The motorcycle experience. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1998, 16, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Doyle, P.; Campbell, O.M.; Rao, G.V.; Murthy, G.V. Transport of pregnant women and obstetric emergencies in India: An analysis of the ‘108’ ambulance service system data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyedu, A.; Stewart, B.; Mock, C.; Otupiri, E.; Nakua, E.; Donkor, P.; Ebel, B.E. Prevalence of preventable household risk factors for childhood burn injury in semi-urban Ghana: A population-based survey. Burns 2016, 42, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaoz, B. First-aid home treatment of burns among children and some implications at Milas, Turkey. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2010, 36, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, M.; von Eichel, J.; Asskali, F. Wound management with coconut oil in Indonesian folk medicine. Chirurg 2002, 73, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.R.; Clark, A.K.; Sivamani, R.K.; Shi, V.Y. Natural oils for skin-barrier repair: Ancient compounds now backed by modern science. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.; Durgaprasad, S. Burn wound healing property of Cocos nucifera: An appraisal. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2008, 40, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akbik, D.; Ghadiri, M.; Chrzanowski, W.; Rohanizadeh, R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014, 116, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldosoky, R.S. Home-related injuries among children: Knowledge, attitudes and practice about first aid among rural mothers. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, G.R. Snake Worship in India; Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2017.

- Anwar, M.; Green, J.; Norris, P. Health-seeking behaviour in Pakistan: A narrative review of the existing literature. Public Health 2012, 126, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, D.J.; Dedicoat, M.J.; Lalloo, D.G. Healthcare-seeking behaviour and use of traditional healers after snakebite in Hlabisa sub-district, Kwazulu Natal. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2007, 12, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, R.W.; Bronzan, R.; Roques, T.; Nyamawi, C.; Murphy, S.; Marsh, K. The prevalence and morbidity of snake bite and treatment-seeking behaviour among a rural Kenyan population. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1994, 88, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediriweera, D.S.; Kasturiratne, A.; Pathmeswaran, A.; Gunawardena, N.K.; Jayamanne, S.F.; Lalloo, D.G.; de Silva, H.J. Health seeking behavior following snakebites in Sri Lanka: Results of an island wide community based survey. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karki, K.B. Snakebite in Nepal: Neglected public health challenge. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2016, 14, I–II. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bansal, C.P. IAP-BLS: The golden jubilee year initiative. Indian Pediatr. 2013, 50, 731–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Children Having an Unintentional Injury n = 1049 (17*%) | Not Received First Aid n = 320 (31%) | Received First Aid n = 729 (69%) | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Boys | 658 (20) | 219 (33) | 439 (67) | 1.48 | 1.216–1.952 | 0.005 |

| Girls | 391 (13) | 101 (26) | 290 (73) | |||

| Age group | ||||||

| 1 month–1 year | 36 (8) | 8 (22) | 28 (78) | R | R | R |

| >1–5 years | 276 (19) | 95 (34) | 181 (66) | 0.73 | 0.322–1.691 | 0.473 |

| >5–10 years | 319 (19) | 93 (29) | 226 (71) | 0.59 | 0.263–1.360 | 0.221 |

| >10–18 years | 418 (15) | 124 (30) | 294 (70) | 0.51 | 0.229–1.160 | 0.110 |

| Location | ||||||

| Rural | 540 (16) | 154 (28) | 386 (72) | 0.92 | 0.713–1.198 | 0.553 |

| Urban | 509 (18) | 166 (33) | 343 (67) |

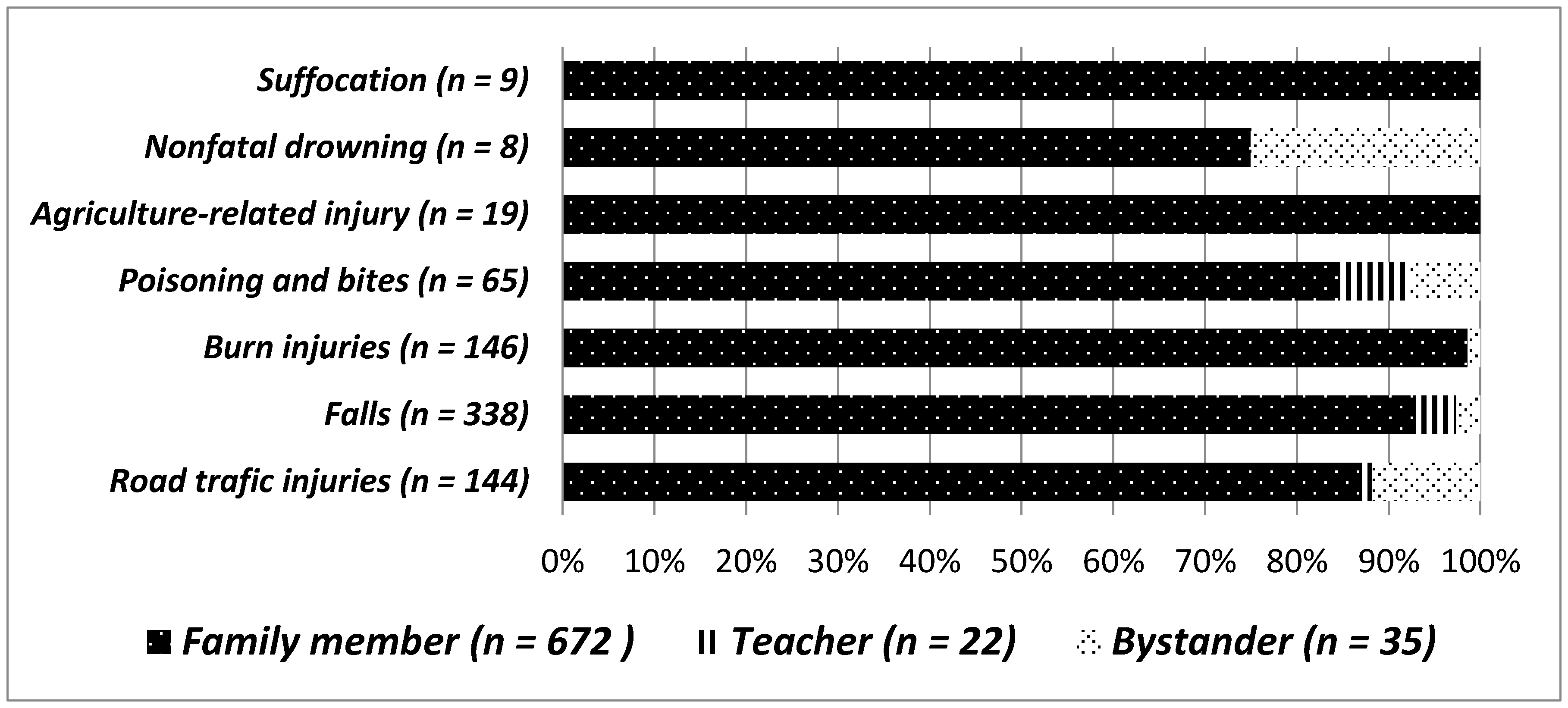

| Injury Type | Total n = 1087 | First Aid Given n = 729 (#%) | Rural Population n = 374 (51*%) | Urban Population n = 355 (49*%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road traffic accidents | 229 | 144 (63) | 73 (51) | 71 (49) |

| Falls | 491 | 338 (69) | 168 (50) | 170 (50) |

| Burns | 170 | 146 (86) | 58 (40) | 88 (60) |

| Poisoning and bites | 126 | 65 (52) | 53 (82) | 12 (18) |

| Agriculture-related injury | 25 | 19 (76) | 18 (95) | 1 (5) |

| Nonfatal drowning | 25 | 8 (32) | 1 (13) | 7 (87) |

| Suffocation | 21 | 9 (43) | 3 (33) | 6 (66) |

| Type of Injury | Total Injuries n = 1087 | Health Care | Place of Seeking Health Care (n = 758) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Sought n = 329 | Sought n = 758 (#%) | Private Setting n = 393 (52*%) | Government Setting n = 194 (26*%) | Informal Health Care Providers n = 171 (22*%) | ||

| Road traffic injuries | 229 (21) | 36 (16) | 193 (84) | 103 (53) | 55 (28) | 35 (18) |

| Falls | 491 (47) | 164 (33) | 327 (67) | 160 (49) | 69 (21) | 98 (30) |

| Burns | 170 (16) | 77 (45) | 93 (55) | 53 (57) | 23 (25) | 17 (18) |

| Poisoning and bites | 126 (12) | 24 (19) | 102 (81) | 54 (53) | 32 (31) | 16 (16) |

| Agriculture-related injury | 25 (2) | 10 (40) | 15 (60) | 7 (46) | 6 (40) | 2 (13) |

| Nonfatal drowning | 25 (2) | 11 (44) | 14 (56) | 7 (50) | 6 (43) | 1 (7) |

| Suffocation | 21 (2) | 7 (33) | 14 (67) | 9 (64) | 3 (21) | 2 (14) |

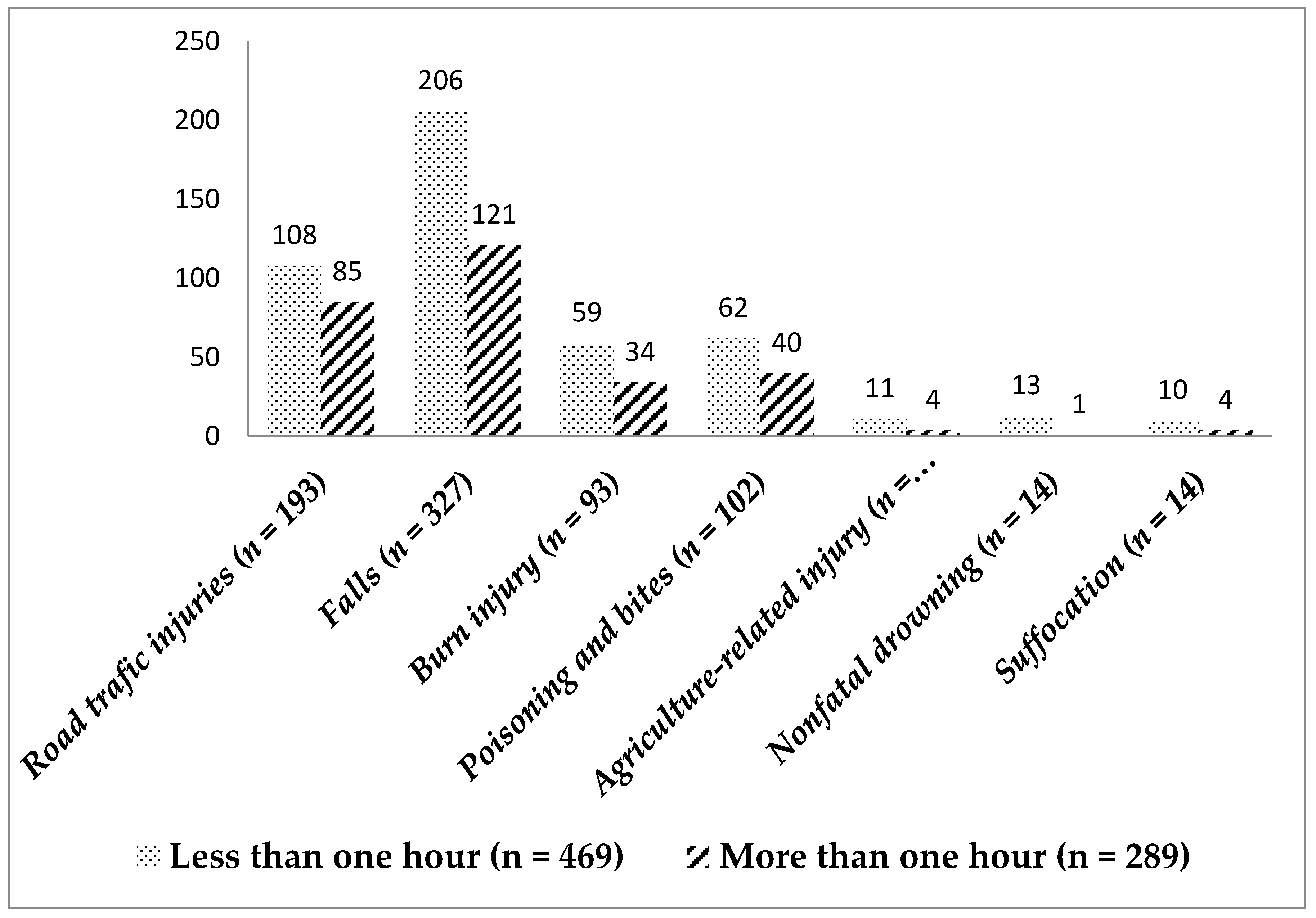

| Type of Injury | Total n = 758 (#%) | Two Wheeler @ n = 360 (47) *% | Public Transport n = 212 (28) *% | Walking n = 144 (19) *% | Others n = 36 (5) *% | Ambulance n = 6 (1) *% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road traffic injuries | 193 (25) | 120 (62) | 40(21) | 24(12) | 5(3) | 4(2) |

| Falls | 327 (43) | 202 (62) | 46 (14) | 71(22) | 7(2) | 1(0) |

| Burns | 93 (12) | 14 (15) | 44(47) | 22(24) | 12(13) | 1(1) |

| Poisoning and bites | 102 (13) | 18 (18) | 56(55) | 19 (19) | 9(9) | 0 |

| Agriculture-related injury | 15 (2) | 0 | 13(86) | 1(7) | 1(7) | 0 |

| Non-fatal drowning | 14 (2) | 2 (14) | 5(36) | 6(43) | 1(7) | 0 |

| Suffocation | 14 (2) | 4 (29) | 8(57) | 1(7) | 1(7) | 0 |

| First Aid Used in Different Injuries | n | *% |

|---|---|---|

| Road traffic injury (n = 144) | ||

| Antiseptic cream | 45 | 31 |

| Coconut oil | 37 | 26 |

| Bandage | 31 | 22 |

| Turmeric powder | 22 | 15 |

| Lime | 14 | 10 |

| Turmeric powder and quick lime | 14 | 10 |

| Falls (n = 338) | ||

| Coconut oil | 130 | 38 |

| Antiseptic cream | 119 | 35 |

| Turmeric powder | 64 | 19 |

| Oil massage | 32 | 9 |

| Lime | 38 | 11 |

| Bandage | 48 | 14 |

| Turmeric powder and coconut oil | 30 | 9 |

| Turmeric powder and quick lime | 38 | 11 |

| Burns (n = 146) | ||

| Coconut oil | 64 | 44 |

| Antiseptic cream | 36 | 25 |

| Toothpaste | 32 | 22 |

| Irrigation with water for 10–20 min over burn area | 19 | 13 |

| Poisoning due to ingestion/inhalation (n = 16) | ||

| Washed with water and soap | 9 | 56 |

| Washed with water | 6 | 38 |

| Poisoning and bites (n = 49) | ||

| Rubbed with metal on bitten area | 15 | 31 |

| Turmeric powder | 10 | 20 |

| Spiritual activities | 22 | 45 |

| Agriculture injury (n = 19) | ||

| Coconut oil | 6 | 32 |

| Tourniquet | 5 | 26 |

| Bandage | 4 | 21 |

| Antiseptic cream | 3 | 16 |

| Washed with water | 2 | 11 |

| Non-fatal drowning (n = 8) | ||

| Prone position | 4 | 50 |

| Mouth to mouth breathing | 3 | 37 |

| Pressed chest to remove water | 1 | 13 |

| Suffocation (n = 9) | ||

| Hilted back to remove the airway obstruction | 5 | 56 |

| Used fingers to remove the airway obstruction | 4 | 44 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pathak, A.; Agrawal, N.; Mehra, L.; Mathur, A.; Diwan, V. First Aid Practices and Health-Seeking Behaviors of Caregivers for Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Ujjain, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2018, 5, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5090124

Pathak A, Agrawal N, Mehra L, Mathur A, Diwan V. First Aid Practices and Health-Seeking Behaviors of Caregivers for Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Ujjain, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Children. 2018; 5(9):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5090124

Chicago/Turabian StylePathak, Ashish, Nitin Agrawal, Love Mehra, Aditya Mathur, and Vishal Diwan. 2018. "First Aid Practices and Health-Seeking Behaviors of Caregivers for Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Ujjain, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study" Children 5, no. 9: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5090124

APA StylePathak, A., Agrawal, N., Mehra, L., Mathur, A., & Diwan, V. (2018). First Aid Practices and Health-Seeking Behaviors of Caregivers for Unintentional Childhood Injuries in Ujjain, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Children, 5(9), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5090124