Obesity-Related Metabolic Risk in Sedentary Hispanic Adolescent Girls with Normal BMI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Body Composition Analyses

2.4. Biochemical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Metabolic Risk Indicators

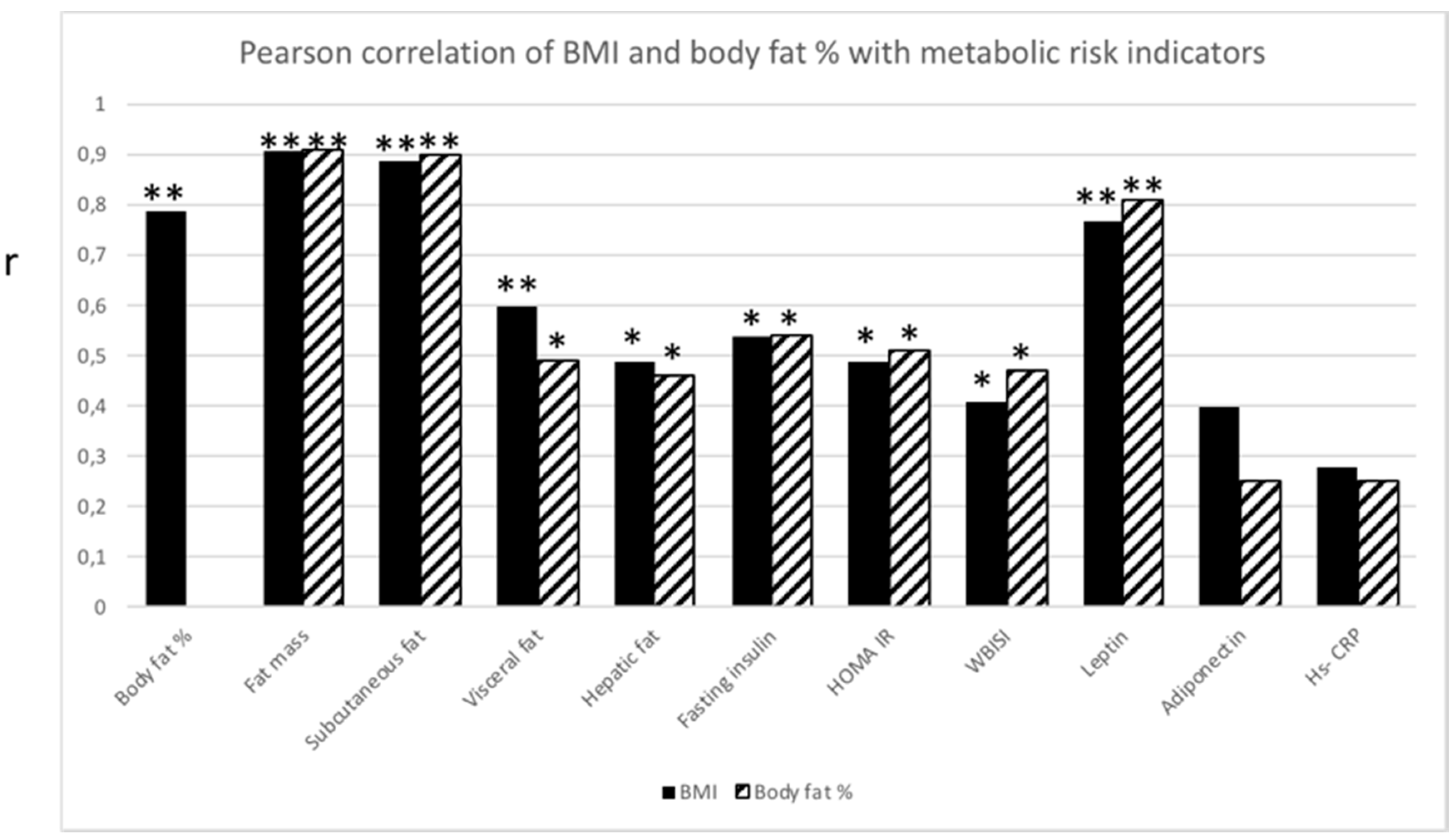

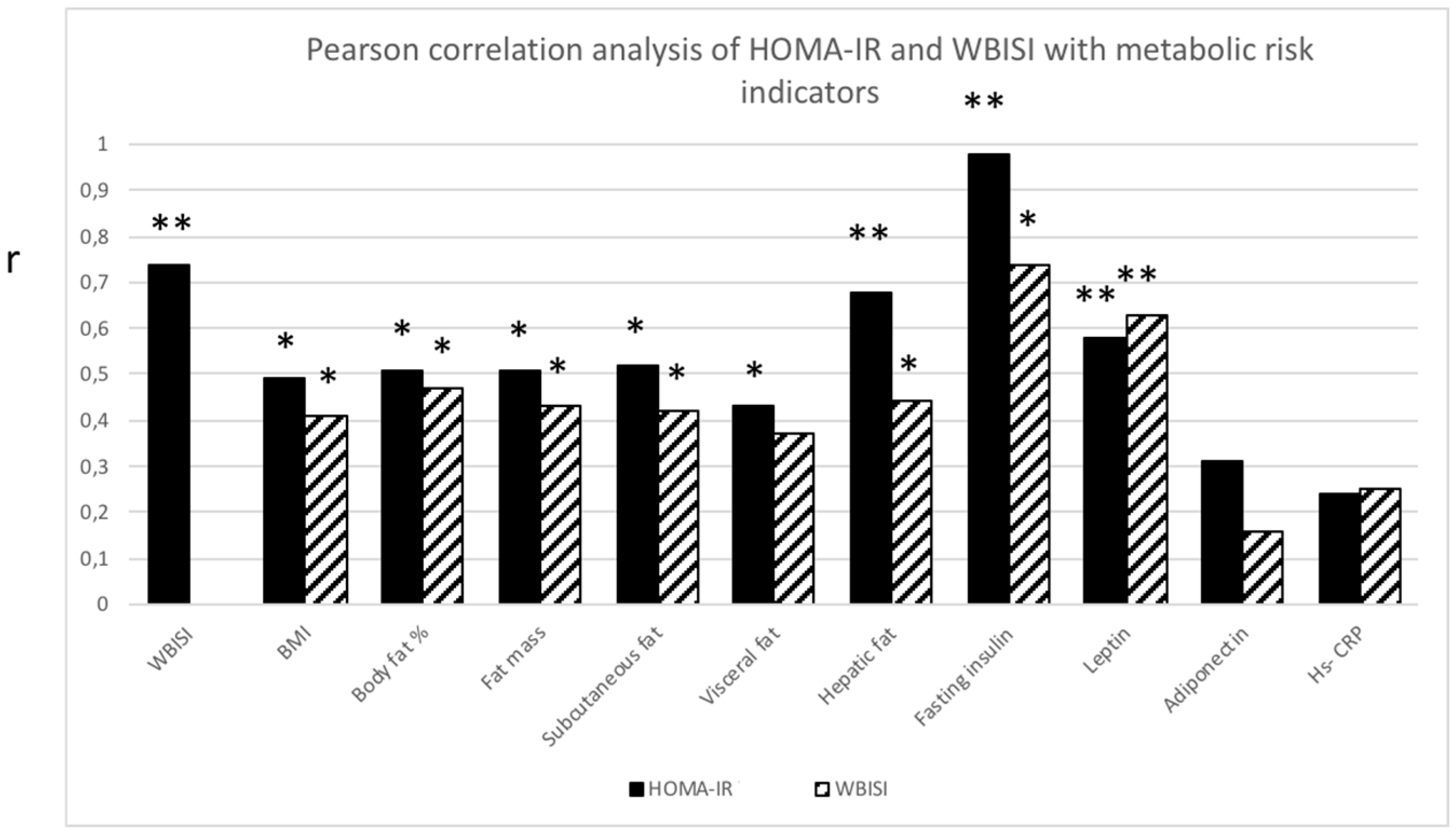

3.3. Correlations of N-BMI (N-BMI-NF and N-BMI-HF Combined)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juonala, M.; Magnussen, C.G.; Berenson, G.S.; Venn, A.; Burns, T.L.; Sabin, M.A.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Daniels, S.R.; Davis, P.H.; Chen, W.; et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Guo, S.S.; Wei, R.; Mei, Z.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv. Data 2000, 314, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, K.J.; Abrams, S.A.; Wong, W.W. Monitoring childhood obesity: assessment of the weight/height index. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 150, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, D.S.; Ogden, C.L.; Berenson, G.S.; Horlick, M. Body mass index and body fatness in childhood. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2005, 8, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegal, K.M.; Ogden, C.L.; Yanovski, J.A.; Freedman, D.S.; Shepherd, J.A.; Graubard, B.I.; Borrud, L.G. High adiposity and high body mass index-for-age in US children and adolescents overall and by race-ethnic group. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutin, B.; Yin, Z.; Humphries, M.C.; Hoffman, W.H.; Gower, B.; Barbeau, P. Relations of fatness and fitness to fasting insulin in black and white adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2004, 145, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, M.M.; Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Lacher, D.A.; Flegal, K.M. Association of body fat percentage with lipid concentrations in children and adolescents: United States, 1999–2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, G.-J.; Wang, Z.J.; Chu, Z.D.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Haymond, M.W.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Sunehag, A.L. A 12-week aerobic exercise program reduces hepatic fat accumulation and insulin resistance in obese, Hispanic adolescents. Obesity 2010, 18, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taksali, S.E.; Caprio, S.; Dziura, J.; Dufour, S.; Calí, A.M.; Goodman, T.R.; Papademetris, X.; Burgert, T.S.; Pierpont, B.M.; Savoye, M.; et al. High visceral and low abdominal subcutaneous fat stores in the obese adolescent: A determinant of an adverse metabolic phenotype. Diabetes 2008, 57, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, S.O.; Hyman, L.D.; Limb, C.H.; McCarthy, S.H.; Lange, R.O.; Sherwin, R.S.; Shulman, G.E.; Tamborlane, W.V. Central adiposity and its metabolic correlates in obese adolescent girls. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 269, E118–E126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liska, D.; Dufour, S.; Zern, T.L.; Taksali, S.; Calí, A.M.; Dziura, J.; Shulman, G.I.; Pierpont, B.M.; Caprio, S. Interethnic differences in muscle, liver and abdominal fat partitioning in obese adolescents. PLoS ONE 2007, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E. Adiposopathy: Is “sick fat” a cardiovascular disease? J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2011, 57, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, S.; Perry, R.; Kursawe, R. Adolescent Obesity and Insulin Resistance: Roles of Ectopic Fat Accumulation and Adipose Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagopal, P.B.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Cook, S.; Daniels, S.R.; Gidding, S.S.; Hayman, L.L.; McCrindle, B.W.; Mietus-Snyder, M.L.; Steinberger, J. Nontraditional risk factors and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease: mechanistic, research, and clinical considerations for youth: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 123, 2749–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, C.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, G.J.; Toffolo, G.; Manesso, E.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Sunehag, A.L. Aerobic exercise increases peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in sedentary adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4292–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, A.M.; McMahon, A.D.; Packard, C.J.; Kelly, A.; Shepherd, J.; Gaw, A.; Sattar, N. Plasma leptin and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the west of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 2001, 104, 3052–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, A.N.; Murphy, M.J.; Metcalf, B.S.; Hosking, J.; Voss, L.D.; English, P.; Sattar, N.; Wilkin, T.J. Adiponectin in childhood. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2008, 3, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A. Ethnic-Specific Criteria for Classification of Body Mass Index: A Perspective for Asian Indians and American Diabetes Association Position Statement. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2015, 17, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudda, M.T.; Nightingale, C.M.; Donin, A.S.; Fewtrell, M.S.; Haroun, D.; Lum, S.; Williams, J.E.; Owen, C.G.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Wells, J.C.; et al. Body mass index adjustments to increase the validity of body fatness assessment in UK Black African and South Asian children. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014, 311, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Deutsch, R.; Kahen, T.; Lavine, J.E.; Stanley, C.; Behling, C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, K.M.V.; Boyle, J.P.; Thompson, T.J.; Sorensen, S.W.; Williamson, D.F. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA 2003, 290, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, G.; Snyder, M.L.; Teng, Y.; Schneiderman, N.; Llabre, M.M.; Cowie, C.; Carnethon, M.; Kaplan, R.; Giachello, A.; Gallo, L.; et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among hispanics/latinos of diverse background: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2391–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, K.J.; Abrams, S.A.; Wong, W.W. Body composition of a young, multiethnic female population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, G.J.; Wang, Z.J.; Chu, Z.; Toffolo, G.; Manesso, E.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Sunehag, A.L. Strength exercise improves muscle mass and hepatic insulin sensitivity in obese youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shypailo, R.J.; Butte, N.F.; Ellis, K.J. DXA: Can it be used as a criterion reference for body fat measurements in children? Obesity 2008, 16, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeckel, C.W.; Weiss, R.; Dziura, J.; Taksali, S.E.; Dufour, S.; Burgert, T.S.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Caprio, S. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepaniak, L.S.; Nurenberg, P.; Leonard, D.; Browning, J.D.; Reingold, J.S.; Grundy, S.; Hobbs, H.H.; Dobbins, R.L. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E462–E468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, T.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Alexander, R.W.; Anderson, J.L.; Cannon, R.O.; Criqui, M.; Fadl, Y.Y.; Fortmann, S.P.; Hong, Y.; Myers, G.L.; et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003, 107, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Okumura, M.J.; Davis, M.M.; Herman, W.H.; Gurney, J.G. Prevalence and determinants of insulin resistance among U.S. adolescents: A population-based study. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2427–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: Comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.; Dziura, J.; Burgert, T.S.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Taksali, S.E.; Yeckel, C.W.; Allen, K.; Lopes, M.; Savoye, M.; Morrison, J.; et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2362–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrannini, E.; Balkau, B.; Coppack, S.W.; Dekker, J.M.; Mari, A.; Nolan, J.; Walker, M.; Natali, A.; Beck-Nielsen, H. Insulin resistance, insulin response, and obesity as indicators of metabolic risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2885–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, P.; Törmäkangas, T.; Shi, Y.; Wu, N.; Vainionpää, A.; Alen, M.; Cheng, S. Normal-weight obesity and cardiometabolic risk: A 7-year longitudinal study in girls from prepuberty to early adulthood. Obesity 2017, 25, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunehag, A.L.; Toffolo, G.; Campioni, M.; Bier, D.M.; Haymond, M.W. Effects of Dietary Macronutrient Intake on Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion and Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Healthy, Obese Adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4496–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Andel, M.; Heijboer, A.C.; Drent, M.L. Adiponectin and Its Isoforms in Pathophysiology. In Advances in Clinical Chemistry; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, P.; Poirier, P.; Pibarot, P.; Lemieux, I.; Després, J.P. Visceral obesity the link among inflammation, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2009, 53, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower, B.A.; Nagy, T.R.; Goran, M.I. Visceral fat, insulin sensitivity, and lipids in prepubertal children. Diabetes 1999, 48, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffeis, C.; Manfredi, R.; Trombetta, M.; Sordelli, S.; Storti, M.; Benuzzi, T.; Bonadonna, R.C. Insulin sensitivity is correlated with subcutaneous but not visceral body fat in overweight and obese prepubertal children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2122–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgert, T.S.; Taksali, S.E.; Dziura, J.; Goodman, T.R.; Yeckel, C.W.; Papademetris, X.; Constable, R.T.; Weiss, R.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Savoye, M.; et al. Alanine aminotransferase levels and fatty liver in childhood obesity: Associations with insulin resistance, adiponectin, and visceral fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 4287–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandi, A.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Martino, F.; Martino, E.; Bozzola, M.; Maffeis, C. Anthropometric indices are not satisfactory predictors of metabolic comorbidities in obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2014, 165, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N-BMI | N-BMI-NF | N-BMI-HF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 8 | 15 |

| Pubertal stage (Tanner) | IV–V | IV–V | IV–V |

| Age (y) | 14.3 ± 1.3 | 14.0 ± 1.1 | 14.5 ± 1.5 |

| Height (m) | 1.56 ± 0.1 | 1.55 ± 0.1 | 1.55 ± 0.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 50.9 ± 7.7 | 43.2 ± 4.4 | 55.1 ± 5.6 ** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.8 ± 2.5 | 18.0 ± 0.9 | 22.3 ± 1.6 ** |

| Body fat % | 29.3 ± 5.3 | 23.1 ± 1.0 | 32.5 ± 2.6 ** |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 34.5 ± 3.9 | 32.0 ± 3.3 | 35.9 ± 3.6 ** |

| Fat mass (kg) | 15.5 ± 4.8 | 10.1 ± 1.6 | 18.4 ± 3.0 ** |

| Subcutaneous fat (cm2) | 184 ± 71 | 110 ± 37 | 224 ± 49 ** |

| Visceral fat (cm2) | 16 ± 10 | 10 ± 6 | 18 ± 10 * |

| Hepatic fat (%) | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.8 ** |

| N-BMI | N-BMI-NF | N-BMI-HF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 8 | 15 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.86 ± 0.37 | 4.91 ± 0.33 | 4.81 ± 0.40 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 10.6 ± 4.8 | 7.9 ± 3.0 | 12.0 ± 5.0 * |

| HOMA-IR | 2.29 ± 1.1 | 1.73 ± 0.7 | 2.59 ± 1.2 * |

| WBISI | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 1.4 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 20.0 ± 12.2 | 8.7 ± 3.5 | 27.5 ± 9.8 ** |

| Adiponectin (mg/mL) | 11.6 ± 6.6 | 14.4 ± 9.5 | 10.1 ± 4.0 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.96 ± 1.39 | 0.31 ± 0.19 | 1.30 ± 1.62 * |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van der Heijden, G.-J.; Wang, Z.J.; Chu, Z.D.; Haymond, M.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Sunehag, A.L. Obesity-Related Metabolic Risk in Sedentary Hispanic Adolescent Girls with Normal BMI. Children 2018, 5, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060079

Van der Heijden G-J, Wang ZJ, Chu ZD, Haymond M, Sauer PJJ, Sunehag AL. Obesity-Related Metabolic Risk in Sedentary Hispanic Adolescent Girls with Normal BMI. Children. 2018; 5(6):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060079

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan der Heijden, Gert-Jan, Zhiyue J. Wang, Zili D. Chu, Morey Haymond, Pieter J. J. Sauer, and Agneta L. Sunehag. 2018. "Obesity-Related Metabolic Risk in Sedentary Hispanic Adolescent Girls with Normal BMI" Children 5, no. 6: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060079

APA StyleVan der Heijden, G.-J., Wang, Z. J., Chu, Z. D., Haymond, M., Sauer, P. J. J., & Sunehag, A. L. (2018). Obesity-Related Metabolic Risk in Sedentary Hispanic Adolescent Girls with Normal BMI. Children, 5(6), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060079