Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Data Collection

- Demographic data: patient age, gender, migration background, patient residence, siblings with life-limiting conditions.

- Clinical information: current symptoms, medication, medical devices, non-pharmacological treatment.

- Characteristics of the referral: principal underlying diagnosis, care goals.

2.2. Statistics

2.3. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Palliative Care Consultative Encounter Characteristics/Treatment Goals

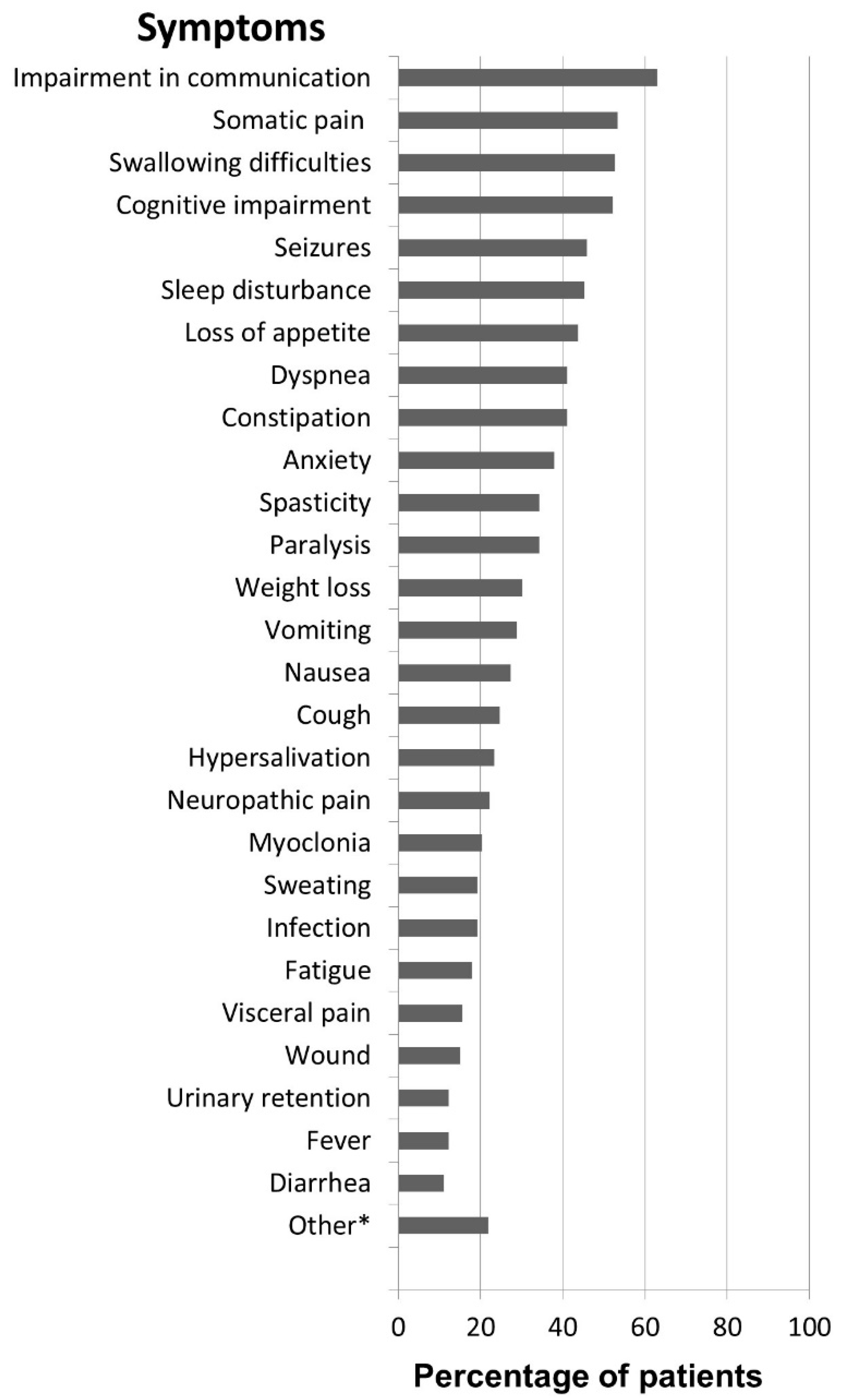

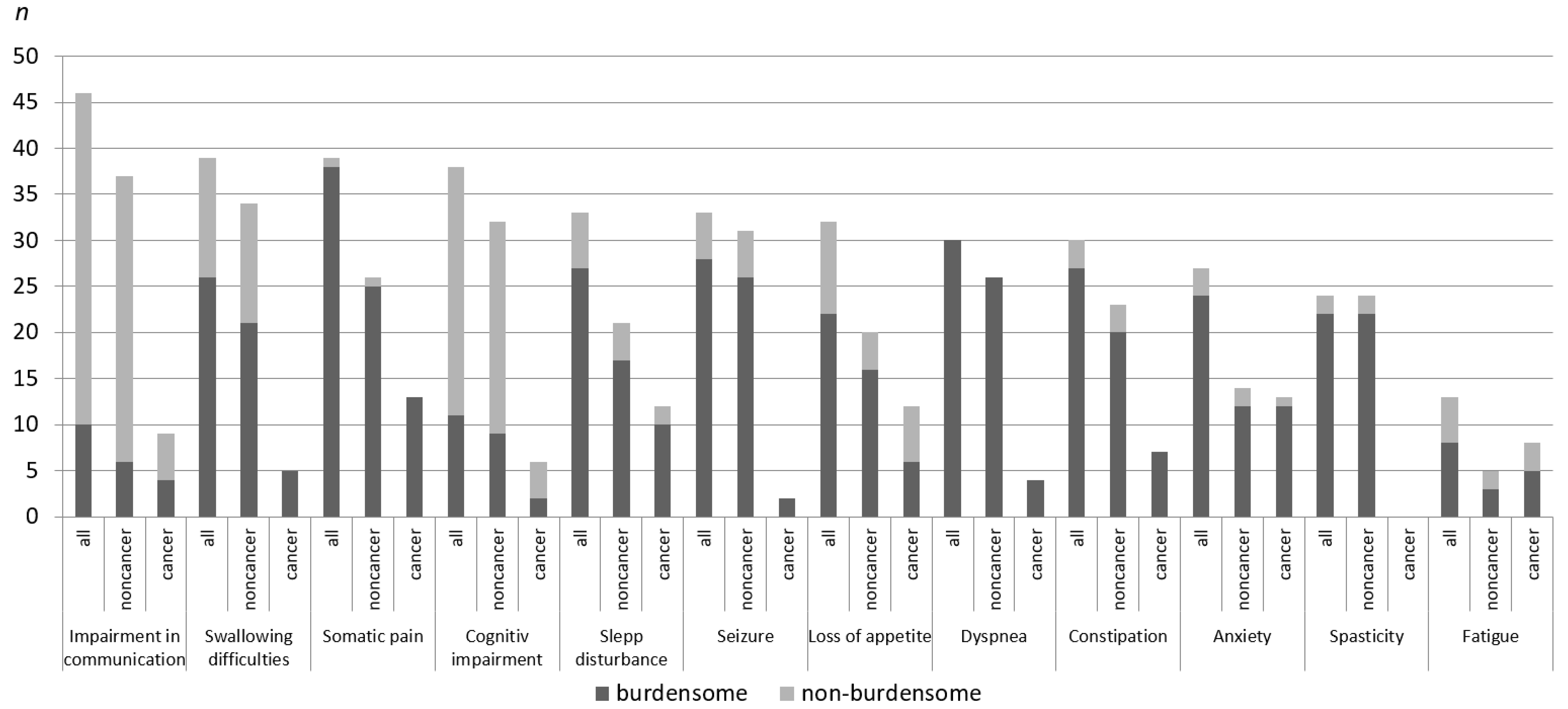

3.3. Symptoms

3.4. Medication and Other Therapy

4. Discussion

4.1. The “Typical” Pediatric Palliative Patient

4.2. Cancer versus Non-Cancer Patients in Pediatric Palliative Care

4.3. The Pediatric Patient Compared with Adult Patients in Palliative Care

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beck, C.H. German Social Law Order Book V–Public Health Sector; Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag: Munich, Germany, 2010; Volume 16, §37b. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, G.; Vyhnalek, B.; Feddersen, B.; Führer, M.; Borasio, G.D. Effectiveness of a specialized outpatient palliative care service as experienced by patients and caregivers. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Wolf, G.; Elsner, F.; Lindena, G.; Hilgers, R.-D.; Heussen, N.; Rolke, R.; Ostgathe, C.; Radbruch, L. Evaluation of 12 pilot projects to improve outpatient palliative care. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 138, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heckel, M.; Stiel, S.; Frauendorf, T.; Hanke, R.; Ostgathe, C. Comparison of patients and their care in urban and rural specialised palliative home care–A single service analysis. Gesundheitswesen 2016, 78, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Groh, G.; Feddersen, B.; Führer, M.; Borasio, G.D. Specialized home palliative care for adults and children: Differences and similarities. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Kamtsiuris, P.; Lange, C.; Rosario, A.S.; Stolzenberg, H.; Lampert, T. Sociodemographic characteristics in the german health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KIGGS)–Operationalisation and public health significance, taking as an example the assessment of general state of health. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007, 50, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feudtner, C.; Kang, T.I.; Hexem, K.R.; Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Osenga, K.; Siden, H.; Friebert, S.E.; Hays, R.M.; Dussel, V.; Wolfe, J. Pediatric palliative care patients: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siden, H.; Chavoshi, N.; Harvey, B.; Parker, A.; Miller, T. Characteristics of a pediatric hospice palliative care program over 15 years. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e765–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburro, R.F.; Shaffer, M.L.; Hahnlen, N.C.; Felker, P.; Ceneviva, G.D. Care goals and decisions for children referred to a pediatric palliative care program. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiel, S.; Matthies, D.M.; Seuss, D.; Walsh, D.; Lindena, G.; Ostgathe, C. Symptoms and problem clusters in cancer and non-cancer patients in specialized palliative care—Is there a difference? J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, S.; Stiel, S.; Hofmann, S.; Klein, C.; Lindena, G.; Ostgathe, C. Trends in specialized palliative care for non-cancer patients in germany—Data from the national hospice and palliative care evaluation (hope). Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 25, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Postier, A.; Dreyfus, J.; Osenga, K.; Sencer, S.; Wolfe, J. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, P.; Otto, M.; Hechler, T.; Metzing, S.; Wolfe, J.; Zernikow, B. Did increased availability of paediatric palliative care lead to improved palliative care outcomes in children with cancer? J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diagnoses (N = 75) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 21 | 28.1 |

| Solid tumor | 11 | 14.7 |

| Brain tumor | 8 | 10.7 |

| Leukemia | 2 | 2.7 |

| Non-Cancer | 54 | 71.9 |

| Neuromuscular | 28 | 37.0 |

| Neurodegenerative | 9 | 12.0 |

| Chromosomal Aberration | 6 | 8.0 |

| Cardiovascular | 6 | 8.0 |

| Respiratory | 1 | 1.3 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 | 1.3 |

| Other a | 3 | 4.0 |

| Characteristics | Total Patients | Cancer Patients | Non-Cancer Patients | Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | df | Chi-Square | p-Value | |

| Gender (n = 69) | 1 | 0.006 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Female | 34 | 49.3 | 10 | 50.0 | 24 | 49.0 | |||

| Male | 35 | 50.7 | 10 | 50.0 | 25 | 51.0 | |||

| Age (N = 75) | 4 | 7.45 | 0.114 | ||||||

| 0–1 month | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | |||

| 2–11 month | 15 | 20.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 14 | 25.9 | |||

| 1–9 years | 27 | 36.0 | 8 | 38.1 | 19 | 35.2 | |||

| 10–18 years | 22 | 29.3 | 10 | 47.6 | 12 | 22.2 | |||

| Older than 18 years | 10 | 13.3 | 2 | 9.5 | 8 | 14.8 | |||

| Migration background | 2 | 0.42 | 0.810 | ||||||

| With migration background 1 | 12 | 16.0 | 3 | 20.0 | 9 | 21.4 | |||

| Residence (N = 75) | 2 | 3.99 | 0.136 | ||||||

| With both parents | 53 | 70.7 | 17 | 81.0 | 36 | 66.6 | |||

| Only/mostly with mother | 13 | 17.3 | 4 | 19.0 | 9 | 16.7 | |||

| Other 2 | 9 | 12 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 16.7 | |||

| Siblings with LLC (n = 72) | 2 | 3.01 | 0.222 | ||||||

| Siblings with LLC | 7 | 9.7 | 0 | 0.00 | 7 | 100.0 | |||

| Characteristics | Total Patients (n = 74) | Cancer Patients (n = 21) | Non-Cancer Patients (n = 53) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-Value c | |

| Counsel a | 69 | 93.2 | 19 | 90.5 | 50 | 94.3 | 0.618 |

| Symptom management | 66 | 89.2 | 20 | 95.2 | 46 | 86.8 | 0.427 |

| Empowerment b | 53 | 71.6 | 13 | 61.9 | 40 | 75.5 | 0.264 |

| Communication about symptoms/course of disease | 51 | 68.9 | 16 | 76.2 | 35 | 66 | 0.578 |

| Decision-making support | 48 | 64.9 | 16 | 76.2 | 32 | 60.4 | 0.282 |

| Transition to home | 15 | 20.3 | 6 | 28.6 | 9 | 17.0 | 0.388 |

| Logistic and coordination of care | 34 | 45.9 | 10 | 47.6 | 24 | 45.3 | 1.000 |

| Discuss DNAR order | 34 | 45.9 | 11 | 52.4 | 23 | 43.4 | 0.606 |

| Consultation of further provider/carer | 25 | 33.8 | 8 | 38.1 | 17 | 32.1 | 0.786 |

| Total Patients n (%) | Cancer Patients n (%) | Non-Cancer Patients n (%) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impairment in communication | 46 (63.0) | 9 (42.9) | 37 (71.2) | 0.033 |

| Swallowing difficulties | 39 (52.7) | 5 (23.8) | 34 (66.0) | 0.002 * |

| Somatic pain | 39 (53.4) | 13 (61.9) | 26 (50.0) | 0.441 |

| Cognitive impairment | 38 (52.1) | 6 (28.6) | 32 (61.5) | 0.019 |

| Seizures | 33 (45.8) | 2 (9.5) | 31 (60.8) | <0.001 * |

| Sleep disturbance | 33 (45.2) | 12 (57.1) | 21 (40.4) | 0.207 |

| Loss of appetite | 32 (43.8) | 12 (57.1) | 20 (38.5) | 0.194 |

| Constipation | 30 (41.1) | 7 (33.3) | 23 (44.2) | 0.441 |

| Dyspnea | 30 (41.1) | 4 (19.0) | 26 (50.0) | 0.019 |

| Anxiety | 27 (38.0) | 13 (65.0) | 14 (27.5) | 0.006 |

| Paralysis | 25 (34.2) | 7 (33.3) | 18 (34.6) | 1.000 |

| Spasticity | 25 (34.2) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (48.1) | <0.001 * |

| Weight loss | 22 (30.1) | 8 (38.1) | 14 (26.9) | 0.403 |

| Vomiting | 21 (28.8) | 8 (38.1) | 13 (25.0) | 0.271 |

| Nausea | 20 (27.4) | 8 (38.1) | 12 (23.1) | 0.248 |

| Cough | 18 (24.7) | 3 (14.3) | 15 (28.8) | 0.241 |

| Hypersalivation | 17 (23.3) | 1 (4.8) | 16 (30.8) | 0.017 |

| Neuropathic pain | 16 (22.2) | 3 (14.3) | 13 (25.5) | 0.365 |

| Myoclonia | 15 (20.3) | 1 (4.8) | 14 (26.4) | 0.053 |

| Infection | 14 (19.2) | 4 (19.0) | 10 (19.2) | 1.000 |

| Sweating | 14 (19.2) | 1 (4.8) | 13 (25.0) | 0.092 |

| Fatigue | 13 (17.8) | 8 (38.1) | 5 (9.6) | 0.007 |

| Visceral pain | 11 (15.5) | 4 (19.0) | 7 (14.0) | 0.721 |

| Wound | 11 (15.1) | 4 (19.0) | 7 (13.5) | 0.719 |

| Urinary retention | 9 (12.3) | 4 (19.0) | 5 (9.6) | 0.269 |

| Fever | 9 (12.2) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (7.5) | 0.107 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (11.0) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (7.7) | 0.216 |

| Other b | 16 | 5 | 11 |

| Characteristics | All Patients | Cancer Patients | Non-Cancer Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | p-Value a | |

| Number of medication (permanent therapy) | 3.80 (2.48) | 0–12 | 3.33 (2.13) | 0–7 | 4.00 (2.61) | 0–12 | 0.305 |

| Number of medication (on demand medication) | 2.44 (2.02) | 0–12 | 2.24 (1.58) | 0–7 | 2.52 (2.19) | 0–12 | 0.595 |

| Medical technology | n | % | n | % | n | % | p-Value b |

| 75 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 54 | 100 | ||

| Any feeding tube | 43 | 57.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 42 | 77.8 | <0.001 * |

| Nasogastric tube | 15 | 20.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 14 | 25.9 | |

| Gastro-or jejunost. tube | 29 | 38.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 53.7 | |

| Central venous catheter | 15 | 20.0 | 11 | 52.4 | 4 | 7.4 | <0.001 * |

| Tracheostomy | 7 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 13.0 | 0.180 |

| Any ventilation | 11 | 14.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 20.4 | 0.028 |

| Invasive ventilation | 6 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 11.1 | |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 5 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 9.3 | |

| Oxygen | 25 | 33.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 24 | 44.4 | 0.003 * |

| VP/VA shunt | 3 | 4.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.188 |

| Other therapy than medication | 51 | 68.0 | 9 | 42.9 | 42 | 77.8 | 0.008 * |

| Physiotherapy | 49 | 65.3 | 8 | 38.1 | 41 | 75.9 | |

| Occupational therapy | 18 | 24.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 16 | 29.6 | |

| Speech therapy | 10 | 13.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 18.5 | |

| Music therapy | 5 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 9.3 | |

| Homeopathy | 5 | 6.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 4 | 7.4 | |

| Art therapy | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | |

| Acupuncture | 0 | 0.0 | |||||

| All Patients | Cancer Patients | Non-Cancer Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-Value a | |

| Permanent medication | 70 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 49 | 100 | |

| Antacids | 28 | 40 | 9 | 42.9 | 19 | 38.8 | 0.794 |

| Anticonvulsants | 25 | 35.7 | 4 | 19.0 | 21 | 42.9 | 0.064 |

| Laxatives | 23 | 32.9 | 6 | 28.6 | 17 | 34.7 | 0.783 |

| Immunotherapeutic | 18 | 25.7 | 5 | 23.8 | 13 | 26.2 | 1.000 |

| Vitamin | 17 | 24.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 16 | 32.7 | 0.014 |

| Strong Opioid | 15 | 21.4 | 8 | 38.1 | 7 | 14.3 | 0.053 |

| Antibiotics | 15 | 21.4 | 6 | 28.6 | 9 | 18.4 | 0.356 |

| Broncholytics | 12 | 17.1 | 1 | 4.8 | 11 | 22.4 | 0.092 |

| Non-Opioid | 11 | 15.7 | 5 | 23.8 | 6 | 12.2 | 0.286 |

| Muscle Relaxants | 11 | 15.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 22.4 | 0.027 |

| Antiemetics | 7 | 10.0 | 6 | 28.6 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.002 * |

| Diuretics | 7 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 14.3 | 0.094 |

| Sedatives | 4 | 5.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 6.1 | 1.000 |

| Mild Opioids | 3 | 4.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 2 | 4.1 | 1.000 |

| Antidepressives | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.300 |

| On demand medication | 70 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 49 | 100 | |

| Non-Opioid | 27 | 38.6 | 7 | 33.3 | 20 | 40.8 | 0.603 |

| Sedatives | 24 | 34.3 | 5 | 23.8 | 19 | 38.8 | 0.280 |

| Anticonvulsants | 24 | 33.8 | 4 | 19.0 | 20 | 40.0 | 0.106 |

| Strong Opioid | 22 | 31.0 | 11 | 52.4 | 11 | 22.0 | 0.023 |

| Laxatives | 16 | 22.9 | 4 | 19.0 | 12 | 24.5 | 0.761 |

| Antiemetics | 15 | 21.4 | 10 | 47.6 | 5 | 10.2 | 0.001 * |

| Mild Opioid | 4 | 5.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 6.1 | 1.000 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nolte-Buchholtz, S.; Zernikow, B.; Wager, J. Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Children 2018, 5, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060066

Nolte-Buchholtz S, Zernikow B, Wager J. Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Children. 2018; 5(6):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060066

Chicago/Turabian StyleNolte-Buchholtz, Silke, Boris Zernikow, and Julia Wager. 2018. "Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study" Children 5, no. 6: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060066

APA StyleNolte-Buchholtz, S., Zernikow, B., & Wager, J. (2018). Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Children, 5(6), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5060066