Saving Little Lives Minimum Care Package Interventions in 290 Public Health Facilities in Ethiopia: Protocol for a Non-Randomized Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Participants

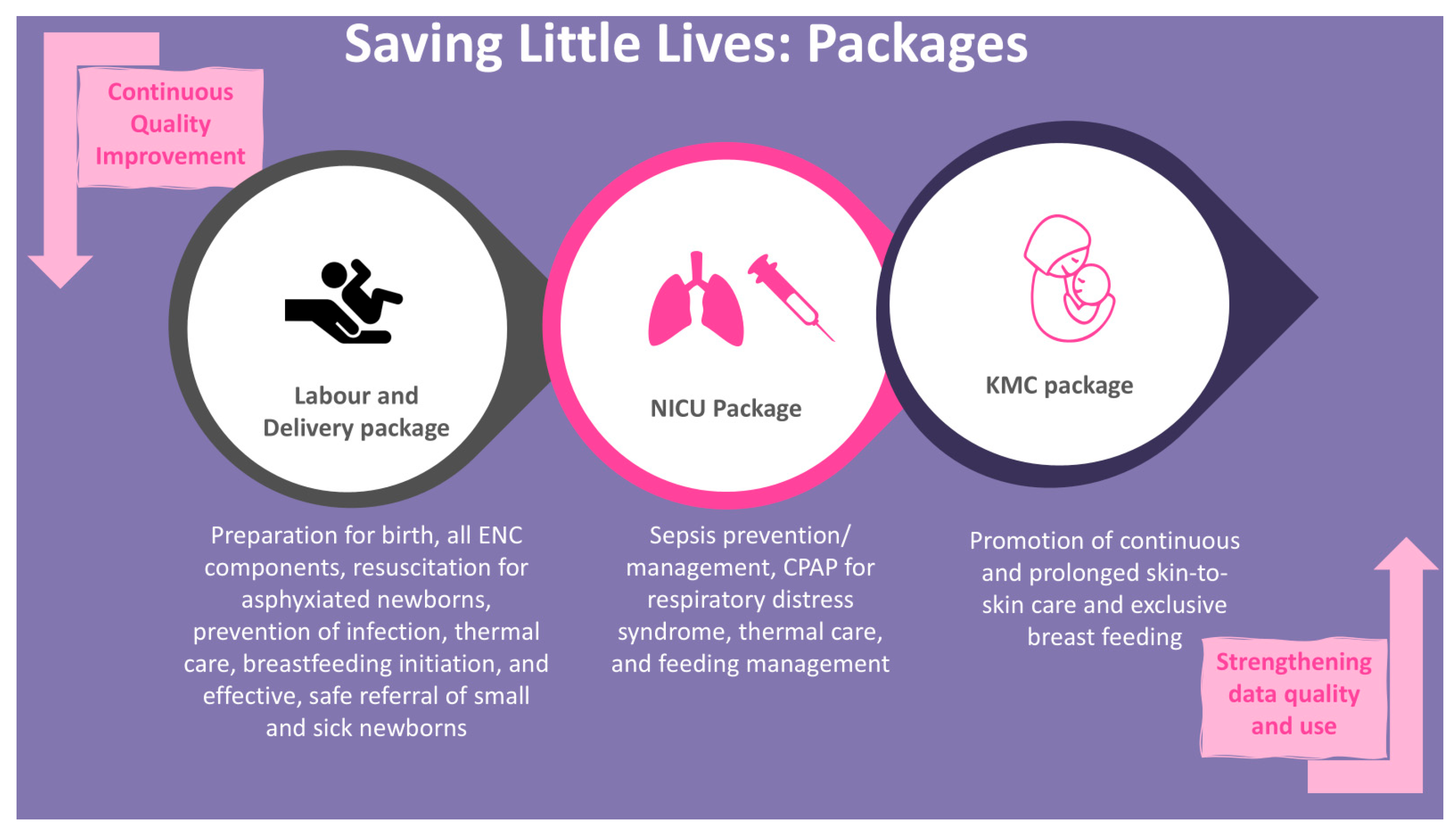

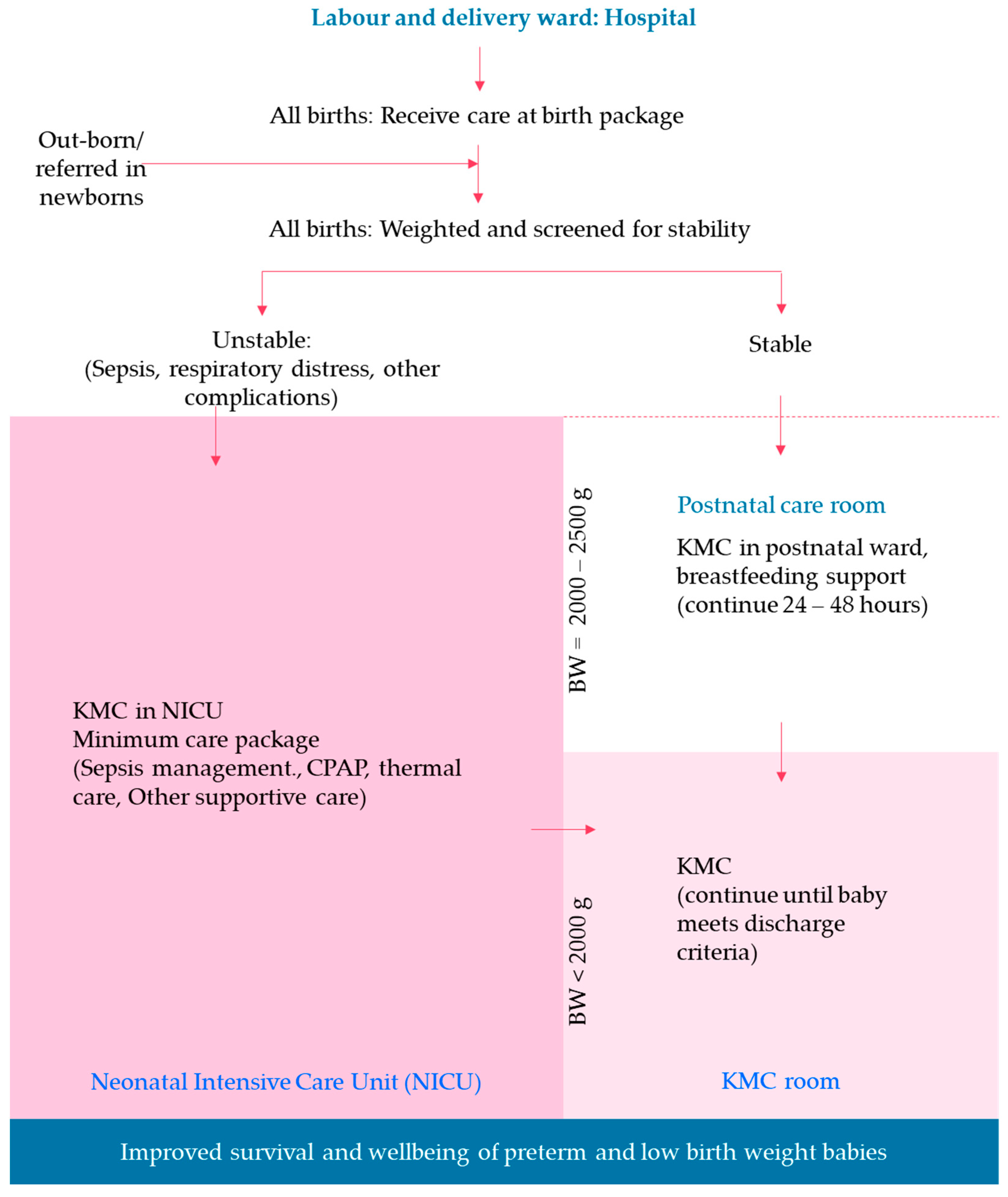

2.4. SLL MCP Intervention Packages

2.5. Implementation Strategy

2.6. Sample Size Estimation

2.7. Data Management

2.7.1. Data Collection Procedure and Tool

2.7.2. Data Sources

2.7.3. Data Quality

2.7.4. Data Analysis

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPAP | Continuous Positive Airway Pressure |

| KMC | Kangaroo Mother Care |

| LBW | Low Birth Weight |

| MCP | Minimum Care Package |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| RDS | Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| SLL | Saving Little Lives |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2023, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, United Nations Children’s Fund, New York, 2024. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/UNICEF-2023-Child-Mortality-Report-1.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Lawn, J.E.; Blencowe, H.; Oza, S.; You, D.; Lee, A.C.; Waiswa, P.; Lalli, M.; Bhutta, Z.; Barros, A.J.; Christian, P.; et al. Every Newborn: Progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet 2014, 384, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blencowe, H.; Krasevec, J.; de Onis, M.; Black, R.E.; An, X.; Stevens, G.A.; Borghi, E.; Hayashi, C.; Estevez, D.; Cegolon, L.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e849–e860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhe, L.M.; McClure, E.M.; Nigussie, A.K.; Mekasha, A.; Worku, B.; Worku, A.; Demtse, A.; Eshetu, B.; Tigabu, Z.; Gizaw, M.A.; et al. Major causes of death in preterm infants in selected hospitals in Ethiopia (SIP): A prospective, cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1130–e1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Ezeaka, C.; Saugstad, O. Ending Preventable Neonatal Deaths: Multicountry Evidence to Inform Accelerated Progress to the Sustainable Development Goal by 2030. Neonatology 2023, 120, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Care of Preterm or Low Birthweight Infants, G. New World Health Organization recommendations for care of preterm or low birth weight infants: Health policy. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. National Newborn and Child Survival Strategy; Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Basic Newborn Resuscitation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, A.R.A.; Aboud, L.; Lavin, T.; Cao, J.; Dore, G.; Ramson, J.; Oladapo, O.T.; Vogel, J.P. Effect of antenatal corticosteroid administration-to-birth interval on maternal and newborn outcomes: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, J.P.; Ramson, J.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Qureshi, Z.P.; Chou, D.; Bahl, R.; Oladapo, O.T. Updated WHO recommendations on antenatal corticosteroids and tocolytic therapy for improving preterm birth outcomes. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1707–e1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16–2019/20 (2008–2012 EFY); Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015.

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Ethiopian National Health Care Quality Strategy 2016–2020; Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015.

- Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Health Sector Transformation Plan II; Ministry of Health Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021.

- Mony, P.K.; Tadele, H.; Gobezayehu, A.G.; Chan, G.J.; Kumar, A.; Mazumder, S.; Beyene, S.A.; Jayanna, K.; Kassa, D.H.; Mohammed, H.A.; et al. Scaling up Kangaroo Mother Care in Ethiopia and India: A multi-site implementation research study. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Fact Sheet—Ethiopia 2020; Ministry of Health Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2024. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.et/index.php/fact-sheets (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Central Statistics Services. Projected Population of Ethiopia—2011; Central Statistics Services: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. Available online: https://ess.gov.et/download/projected-population-of-ethiopia-20112019// (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Ugwa, E.; Kabue, M.; Otolorin, E.; Yenokyan, G.; Oniyire, A.; Orji, B.; Okoli, U.; Enne, J.; Alobo, G.; Olisaekee, G.; et al. Simulation-based low-dose, high-frequency plus mobile mentoring versus traditional group-based trainings among health workers on day of birth care in Nigeria; a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, M.A.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breimaier, H.E.; Heckemann, B.; Halfens, R.J.; Lohrmann, C. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): A useful theoretical framework for guiding and evaluating a guideline implementation process in a hospital-based nursing practice. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemming, K.; Haines, T.P.; Chilton, P.J.; Girling, A.J.; Lilford, R.J. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015, 350, h391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Estimated Total Population | Estimated Total Annual Births | Estimated Total Annual <2500 g Births | Estimated Total Annual <2000 g Births | Estimated Total Annual Preterm Births |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tigray | 5,541,997 | 139,455 | 10,599 | 4184 | 13,946 |

| Amhara | 22,192,000 | 342,600 | 76,057 | 10,278 | 34,260 |

| Oromia | 38,170,000 | 528,588 | 69,245 | 15,858 | 52,859 |

| SNNP | 10,371,000 | 267,233 | 35,008 | 8017 | 26,723 |

| Total | 76,274997 | 1,277,876 | 190,908 | 38,336 | 127,788 |

| Phases | 3 Months | 9 Months | 3 Months | 9 Months | 3 Months | 9 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Routine practice | Intervention * | ||||

| Phase 2 | Routine practice | Routine practice | Routine practice | Intervention | ||

| Phase 3 | Routine practice | Routine practice | Routine practice | Routine practice | Routine practice | Intervention |

| Continuous program learning data collection, analysis, and use to inform intervention refinement and improve program performance | ||||||

| Study Component | Design | Participants | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of the impact of the SLL MCP interventions | Non-randomized stepped-wedge design | Mother–newborn dyads: all live births who receive care at the 36 evaluation primary hospitals | Independent evaluation research assistants collect data by interviewing mothers and family members, reviewing medical charts and registers |

| Assess facility readiness, barriers, and facilitators of SLL MCP implementation | A mixed method cross-sectional formative assessment | Health facility managers, healthcare providers, and mothers who give birth at the hospitals and mothers with a (preterm) newborn/s admitted to NICU and KMC units | Facility observation, interviews with facility managers, healthcare providers, and mothers |

| Document program learning during SLL MCP implementation | Continuous qualitative assessment | Facility managers, healthcare providers, and mothers who give birth at the hospitals and mothers with a (preterm) newborn/s admitted to NICU and KMC units | Interviews with facility managers, healthcare providers, and mothers |

| Assess the cost effectiveness of the SLL MCP interventions | Cost description and cost analysis on the incremental cost of scaling up the SLL MCP interventions in the hospitals | Project managers, facility managers, and healthcare providers | Review of program financial reports, interview of project managers, facility managers, and healthcare providers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Estifanos, A.S.; Gobezayehu, A.G.; Argaw, M.S.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Hailemariam, D.; Kassahun, B.N.; Beyene, S.A.; Tadele, H.; Endalamaw, L.A.; Aredo, A.D.; et al. Saving Little Lives Minimum Care Package Interventions in 290 Public Health Facilities in Ethiopia: Protocol for a Non-Randomized Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Trial. Children 2026, 13, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020187

Estifanos AS, Gobezayehu AG, Argaw MS, Medhanyie AA, Hailemariam D, Kassahun BN, Beyene SA, Tadele H, Endalamaw LA, Aredo AD, et al. Saving Little Lives Minimum Care Package Interventions in 290 Public Health Facilities in Ethiopia: Protocol for a Non-Randomized Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Trial. Children. 2026; 13(2):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020187

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstifanos, Abiy Seifu, Abebe Gebremaraim Gobezayehu, Mekdes Shifeta Argaw, Araya Abrha Medhanyie, Damen Hailemariam, Bezaye Nigussie Kassahun, Selamawit Asfaw Beyene, Henok Tadele, Lamesgin Alamineh Endalamaw, Abebech Demissie Aredo, and et al. 2026. "Saving Little Lives Minimum Care Package Interventions in 290 Public Health Facilities in Ethiopia: Protocol for a Non-Randomized Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Trial" Children 13, no. 2: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020187

APA StyleEstifanos, A. S., Gobezayehu, A. G., Argaw, M. S., Medhanyie, A. A., Hailemariam, D., Kassahun, B. N., Beyene, S. A., Tadele, H., Endalamaw, L. A., Aredo, A. D., Kahsay, Z. H., Kotiso, K. S., Alemayehu, A., Belew, M. L., Berhe, A. H., Weldebirhan, S. N., Dimtse, A., Dangisso, M. H., Amare, S. Y., ... Duguma, D. (2026). Saving Little Lives Minimum Care Package Interventions in 290 Public Health Facilities in Ethiopia: Protocol for a Non-Randomized Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Trial. Children, 13(2), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13020187