Socio-Emotional Wellbeing in Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Method

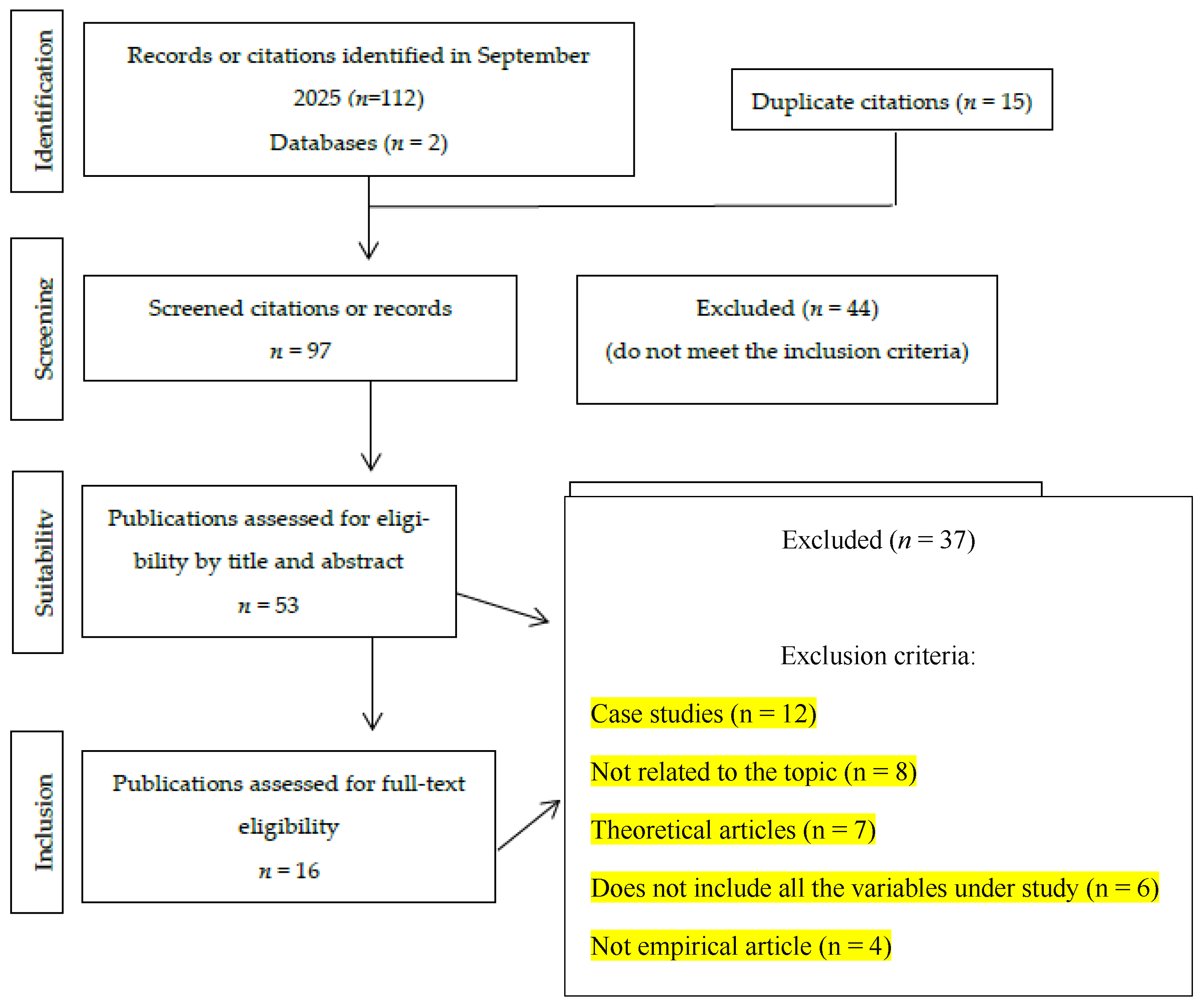

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Year of Publication, Language, Journal, and Country

3.2. Variables Related to Participants in the Studies Analysed

3.3. Methodological Characteristics of the Studies Analysed

3.4. Description of the Interventions in the Reviewed Studies

3.5. Principal Results and Findings from the Analysed Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chua, J.Y.X.; Shorey, S. The effect of mindfulness-based and acceptance commitment therapy-based interventions to improve the mental well-being among parents of children with developmental disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 2770–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zablotsky, B.; Black, L.I.; Maenner, M.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Bitsko, R.H.; Blumberg, S.J.; Kogan, M.D.; Boyle, C.A. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition Text Revision DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.appi.org/dsm-5-tr (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Ahmed, A.N.; Raj, S.P. Self-compassion intervention for parents of children with developmental disabilities: A feasibility study. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2023, 7, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abín, A.; Pasarín-Lavín, T.; Areces, D.; Rodríguez, C.; Núñez, J.C. The emotional impact of family involvement during homework in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review. Children 2024, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueli, M.; Martín, N.; Canamero, L.M.; Rodríguez, C.; González-Castro, P. The impact of children’s and parents’ perceptions of parenting styles on attention, hyperactivity, anxiety, and emotional regulation. Children 2024, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Gotlieb, R.J.M.; Kim, S.A.; Pedroza, V.; Rhinehart, L.V.; Tempini, M.L.G.; Sears, S. Towards a dynamic, comprehensive conceptualization of dyslexia. Ann. Dyslexia 2024, 74, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivette, C.M.; Dunst, C.J.; Hamby, D.W. Influences of family-systems intervention practices on parent-child interactions and child development. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2010, 30, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerihun, T.; Kinfe, M.; Koly, K.N.; Abdurahman, R.; Girma, F.; Team, W.; Hanlon, C.; de Vries, P.J.; Hoekstra, R.A. Non-specialist delivery of the WHO Caregiver Skills Training Programme for children with developmental disabilities: Stakeholder perspectives about acceptability and feasibility in rural Ethiopia. Autism 2024, 28, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.P. Do children with intellectual and developmental disabilities have a negative impact on other family members? The case for rejecting a negative narrative. Int. Rev. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 51, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, V.E.; Matthews, J.M.; Crawford, S.B. Development and preliminary validation of a parenting self-regulation scale: “Me as a Parent” (MaaP). J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 2853–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.M.; Wilson, C.E.; Sharry, J. Parents Plus parenting programme for parents of adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A cluster randomised controlled trial. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 36, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.L.; Kardell, Y.; Hall, S.; Magaa, S.; Reynolds, M.; Crdova, J. A research agenda to support families of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities with intersectional identities. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 62, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, R.L.; Walch, T.J. The glue that keeps everybody together: Peer support in mothers of young children with special health care needs. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunsky, Y.; Albaum, C.; Baskin, A.; Hastings, R.P.; Hutton, S.; Steel, L.; Wang, W.; Weiss, J.A. Group virtual mindfulness-based intervention for parents of autistic adolescents and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3959–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, S.; Hesla, M.W.; Stadskleiv, K. Gaining super control: Psychoeducational group intervention for adolescents with mild intellectual disability and their parents. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 26, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, A.L.; Lunsky, Y.; Lake, J.; Mills, J.S.; Fung, K.; Steel, L.; Weiss, J.A. Parent, child, and family outcomes following Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for parents of autistic children: A randomized controlled trial. Autism 2024, 28, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.N.; Meadan, H.; Ostrosky, M.M. Effects of parent-delivered aided language modeling during shared storybook reading. J. Early Interv. 2017, 38, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, L.L. Improving interactions between parents, teachers, and staff and individuals with developmental disabilities: A review of caregiver training methods and results. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 66, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodder, A.; Papadopoulos, C.; Randhawa, G. SOLACE: A psychosocial stigma protection intervention to improve the mental health of parents of autistic children—A feasibility randomized controlled trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4477–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.K.; Volpe, T.; St. John, L.; Thakur, A.; Steel, L.; Baskin, A.; Durbin, A.; Chacra, M.A.; Lunsky, Y. Mental health and COVID-19: The impact of a virtual course for family caregivers of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2022, 66, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Harris, S.P.; Hsieh, K. Formal support and service needs of family caregivers of adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities in India. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2024, 37, e13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanasionok, M.M.; Paris, A.; Griffin, J.; Hastings, R.P.; Finch, E.; Austin, D.; Flynn, S. Digital psychological wellbeing interventions for family carers of children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2025, 38, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, S.E.; Duijff, S.N.; Campbell, L.E. Care4Parents: An evaluation of an online mindful parenting program for caregivers of children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2025, 9, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffman, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Res. Methods Rep. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, T.H.; Renhorn, E.; Berg, B.; Lappalainen, P.; Ghaderi, A.; Hirvikoski, T. Acceptance and commitment therapy group intervention for parents of children with disabilities: Navigator ACT, an open feasibility trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 1834–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boule, M.; Rivard, M.; Mello, C. Parents’ emotional journey throughout their participation in a well-being support group intervention. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2025, 38, e70107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyük, D.Ş.; Özmen, D. Effectiveness of a parent empowerment program for parents of children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Child Care Health Dev. 2025, 51, e70148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fante, C.; Musetti, A.; De Luca Picione, R.; Dioni, B.; Manari, T.; Raffin, C.; Capelli, F.; Franceschini, C.; Lenzo, V. Parental quality of life and impact of multidisciplinary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders: A qualitative study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2025, 55, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, N.; Bradshaw, J.; Hastings, R.; Sweeney, J.; Austin, D. Early Positive Approaches to Support (E-PAtS): Qualitative experiences of a new support programme for family caregivers of young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 35, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.T.; Lee, V.; Vashi, N.; Roudbarani, F.; Modica, P.T.; Pouyandeh, A.; Sellitto, T.; Ameis, S.H.; Elkader, A.; Gray, K.M.; et al. Parent outcomes following participation in cognitive behavior therapy for autistic children in a community setting: Parent mental health, mindful parenting, and parenting practices. Autism Res. 2025, 18, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, B.; Frost, K.M.; Straiton, D.; Ramos, A.P.; Howard, M. Relative efficacy of self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth models of a parent-mediated intervention for autism: Examining effects on parent intervention fidelity, well-being, and program engagement. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 3605–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondrušková, T.; Oulton, K.; Royston, R.; Hassiotis, A. Process evaluation of a parenting intervention for preschoolers with intellectual disabilities who display behaviours that challenge in the UK. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2024, 37, e13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, K.; Patel, M.; Krishna, D.; Venkatachalapathy, N.; Brien, M.; Langlois, S. A capacity-building intervention for parents of children with disabilities in rural South India. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 150, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safer-Lichtenstein, J.; McIntyre, L.L.; Rodriguez, G.; Gomez, D.; Puerta, S.; Neece, C.L. Feasibility and acceptability of Spanish-language parenting interventions for young children with developmental delays. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 61, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, L.; Chambers, N.; Rosenstein, D.; Erasmus, P.; WHO CST Team; de Vries, P.J. Supporting caregivers of children with developmental disabilities: Findings from a brief caregiver well-being programme in South Africa. Autism 2024, 28, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, J.M.; Millan, M.E.; Uljarevic, M.; Gengoux, G.W. Resilience intervention for parents of children with autism: Findings from a randomized controlled trial of the AMOR method. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 52, 7387–7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.; Flynn, S.; Griffin, J.; Hastings, R.P. Programme recipient and facilitator experiences of Positive Family Connections for families of children with intellectual disabilities and/or who are autistic. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2025, 38, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.P.L.; Suarez-Balcazar, Y.; Errisuriz, V.L.; Parra-Medina, D.; Mirza, M.; Zhang, M.; Lee, P.-C.; Zeng, W.; Brown-Hollie, J.P.; Mendoza, E.Y.; et al. PODER Familiar: A culturally tailored health intervention for Latino families of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2025, 38, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, H.; Inoue, M. Evaluating outcomes of a community-based parent training program for Japanese children with developmental disabilities: A retrospective pilot study. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 70, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, E.; Rieth, S.; Mejia, Y.; Cervantes, L.; Vazquez, B.B.; Brookman-Frazee, L. Community-led adaptations of a promotora-delivered intervention for Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2024, 33, 3812–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidhane, A.; Telrandhe, S.; Holding, P.; Patil, M.; Kogade, P.; Jadhav, N.; Khatib, M.N.; Zahiruddin, Q.S. Effectiveness of family-centered program for enhancing competencies of responsive parenting among caregivers for early childhood development in rural India. Acta Psychol. 2022, 229, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Brown, S.; Flynn, S.; Finch, E.; Hastings, R.P.; Austin, D. Experiences of peer mentors in digital wellbeing interventions: Supporting family carers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2025, 38, e70102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone-Heaberlin, M.; Blackburn, A.; Qian, C. Caregiver education programme on intellectual and developmental disabilities: An acceptability and feasibility study in an academic medical setting. Child Care Health Dev. 2023, 50, e13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, B.; Izar, R.; Tran, H.; Akers, K.; Aranha, A.N.F.; Afify, O.; Janks, E.; Mendez, J. Medical student program to learn from families experiencing developmental disabilities. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 70, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, A.H.; Hughes, M.T. Using eCoaching to support mothers’ pretend play interactions at home. Early Child. Educ. J. 2024, 52, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaidi, I.; Drigas, A. Parents’ involvement in the education of their children with autism related research and its results. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Ketelaar, M.; van Nispen Tot Sevenaer, J.; Downs, Z.; van Rappard, D.; Jongmans, M.; Zinkstok, J. Exploring individual parent-to-parent support interventions for parents caring for children with brain-based developmental disabilities: A scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Variable | Fr | % |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | ||

| 2020 | 1 | 6.25 |

| 2021 | 1 | 6.25 |

| 2022 | 1 | 6.25 |

| 2023 | 4 | 25.0 |

| 2024 | 3 | 18.75 |

| 2025 | 6 | 37.50 |

| Language | ||

| English | 16 | 100.0 |

| Journal | ||

| Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders | 1 | 6.25 |

| Autism | 1 | 6.25 |

| Autism Research | 1 | 6.25 |

| Child: Care, Health and Development | 1 | 6.25 |

| Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities | 5 | 31.25 |

| Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 5 | 31.25 |

| Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability | 1 | 6.25 |

| Research in Developmental Disabilities | 1 | 6.25 |

| Sample Country | ||

| Canada | 2 | 12.50 |

| USA | 5 | 31.25 |

| United Kingdom | 4 | 25.0 |

| India | 1 | 6.25 |

| Italy | 1 | 6.25 |

| South Africa | 1 | 6.25 |

| Sweden | 1 | 6.25 |

| Turkey | 1 | 6.25 |

| Total | 16 | 100.00 |

| Authors (Year) | Objective | Participants | Methodological Design | Measures (Instruments) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (2023) [4] | Evaluate the feasibility of a short, asynchronous, online intervention focused on promoting self-compassion. | 50 parents (48 mothers, 2 fathers; mean age: 42.1 years), with children aged between 3 and 17 years old with: Down syndrome, ASD, ADHD, intellectual disability, overall developmental delay, others (spina bifida, cerebral palsy, apraxia, oppositional defiant disorder). | Pre-post design, without control group. | - Self-compassion (SCS scale). - Overall wellbeing (WEN-WBS). - Depression and stress (DASS-21). - Feasibility (Bowen’s model: 5 dimensions). |

| Bergman et al. (2023) [26] | Evaluate the feasibility and preliminary results of a group intervention based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. | 94 parents (85 mothers, 9 fathers) of children with various disorders (ASD, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, among others), with children aged 2 to 17 years old. | Pre, post, and follow up design, without control group. | - Parental stress (PSS). - Anxiety and depression (HADS). - Experiential avoidance in parenting (PAAQ). - Mindfulness (MAAS). - Strengths and difficulties in the children (SDQ). - Satisfaction, credibility, and usefulness of the intervention (CEQ; SEF & PEF). |

| Boule et al. (2023) [27] | Examine the emotional experience during a group support program for wellbeing. | 104 parents (mainly mothers: 92 versus 8 fathers) of children up to 7 years old with intellectual disability and developmental difficulties. | Qualitative longitudinal study with repeated measures based on emotion journals and self-reports. | Emotional experience (online emotion journal). |

| Buyuk & Ozmen (2025) [28] | Evaluate the effectiveness of an empowerment programme based on reducing stress, improving self-efficacy and family empowerment. | 69 mothers of children with ASD aged 6 to 14 years old: - Experimental group: 34. - Control group: 35. | Randomised controlled trial with two non-blinded parallel groups. - Experimental group: 4 training sessions and 2 individual motivational interviews. - Control group: standard practice. Pre and post design | - Parental self-efficacy (PSES). - Carer overload (ZCBS). - Perceived stress (PSS-14). - Family empowerment (FES). |

| Fante et al. (2025) [29] | Explore the impact of ASD on quality of life, and how a multidisciplinary intervention with parental participation influences quality of life and the process of adaptation. | 31 parents (16 mothers and 15 fathers: 42.55 years old), with children diagnosed with level 2 or 3 ASD severity, aged 5 to 11 years old. | Qualitative transversal study based on semi-structured interviews, with inductive (bottom up) thematic analysis without a control group. | Quality of life: semi structured interview about quality of life, parents’ experiences, perception of the intervention, difficulties, and available resources. |

| Gore et al. (2022) [30] | Explore experiences after attending a group intervention programme, as well as the group processes and mechanisms from the carers’ perspectives. | 35 family carers (90% mothers; mean age 36.9 and 38.8 years old) of children aged 2 to 4 years old presenting overall developmental delay, Down syndrome, ASD, or other genetic conditions. | Qualitative study based on individual interviews and focus groups about the experience held after the intervention. | Interviews and focus groups about: - Emotional wellbeing and resilience. - Feelings of belonging and group social support. - Parental self-efficacy. - Coping with stress. - Self-care. - Strategies to deal with challenging behaviours and improve family emotional balance. |

| Ibrahim et al. (2025) [31] | Analyse changes in mental health, mindful parenting, and parenting practice after participation in a community cognitive-behavioural group therapy programme. | 77 parent–child dyads (mean age: 42.47 years old): verbally capable autistic children aged 8–13 years old. | Quasi-experimental pre-post study, without a control group. | - Stress and anxiety (DASS-21). - Mindful parenting (BMPS). - Parenting practices and family adjustment (PAFAS). |

| Ingersoll et al. (2024) [32] | Compare effectiveness of 2 parent-mediated distance intervention models (self-guided and with therapeutic support) in fidelity to the intervention, wellbeing, and engagement with the programme. | 64 parents (mean age: 35.27 years old) of autistic children aged 1.5 to 8 years old. | Randomised controlled trial with 3 parallel groups. Pre and post evaluation and follow up. | - Parental self-efficacy (PSOC). - Knowledge about the intervention. - Perceived positive impact (FIQ). - Parental stress (PSI-SF). - Acceptability and satisfaction (STP). - Perceived obstacles (BTPS). - Technological fluency (CEW). - Expectations (CEP-Q). |

| Lodder et al. (2020) [20] | Evaluate feasibility, acceptability, and initial impact of a programme aimed at improving mental health and how it helps in protecting against stigmatisation. | 17 parents of children with ASD up to 10 years old: - Experimental group: 9. - Control group: 8. | Randomised controlled trial with mixed quantitative and qualitative measures. Pre, post, and follow-up evaluations. | - Mental health (MHI-5). - Stigma (PCSS). - Self-esteem (Rosenberg’s scale). - Self-compassion (SCS-SF). - Positive meaning in the role of carer, self-blame, perceived social support (MOS). - Social isolation (UCLA). - Feasibility (retention and attendance rates, Fidelity of implementation, opinions about randomisation). - Acceptability (participation in focus groups, satisfaction comments, quantitative indicators). |

| Ondrušková et al. (2023) [33] | Evaluate implementation process of a group intervention. | 261 parent–child dyads (children aged 2.5 to 5 years old presenting moderate to severe intellectual disability, with challenging or problematic behaviours): - Experimental group: 155. - Control group: 106. | Evaluation of process within a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. | - Fidelity (checklist adapted from the i-Basis Intervention Fidelity Rating Scale). - Dose and reach (attendance data). - Adaptations (systematic record of adaptations). - Acceptability (semi-structured individual topic interviews and parental satisfaction questionnaire). |

| Proctor et al. (2024) [34] | Evaluate the impact of a group intervention for reinforcing skills, focused on empowerment, peer support, social inclusion, exchange of knowledge and defensive skills. | 37 parents who participated in 17 parent groups, with children under 10 who had developmental difficulties. A rural setting in the south of India. | Qualitative study based on focus groups held 6 months after the intervention, analysed via hybrid thematic analysis (deductive and inductive). | - Experiences of peer support, social inclusion, knowledge exchange, and exchange of defensive skills (discussion guide in focus groups). |

| Safer-Lichtenstein et al. (2023) [35] | Evaluate feasibility and acceptability of 2 parental interventions. | 60 carers (mainly mothers) of children aged 0 to 5 years old with developmental delays. Split into two intervention groups: - Group 1: 30. - Group 2: 30. Spanish speakers residing in the United States. | Randomised controlled trial with a mixed approach. Pre, post, and follow-up evaluations. | - Parental satisfaction (PSQ). - Parental stress (PS-4-SF). - Childish behaviour (CBCL). - Acculturation (VIA). - Session attendance. -Assessment of the experience, challenges, value (focus groups). |

| Schelbusch et al. (2024) [36] | Evaluate feasibility, acceptability, and possible impact of a short wellbeing programme based on acceptance and commitment therapy. | 10 carers (9 mothers and 1 grandmother; Mean age: 41.27 years old) of children with developmental difficulties aged between 4 and 11 years old. Participants were residents in a rural community with limited resources in South Africa. | Quasi-experimental pilot study. Pre and post evaluation without a control group. | - Psychological Flexibility (AAQ-II). - Depression (PHQ-9). - Anxiety (GAD-7). - Perceived social support (MSPSS). - Positive and negative impact of the disability on the family (FICD). - Parental wellbeing (McConkey). - Feasibility and acceptability (ad hoc feedback and post-session satisfaction form). |

| Schwartzman et al. (2021) [37] | Evaluate the efficacy of an intervention to increase resilience and reduce parental stress, and explore collateral effects on family, marriage, and child functioning. | 35 parents of children with ASD aged between 4 and 11 years old. | Randomised controlled trial with two groups. Pre, post, and follow-up evaluations. | - Resilience (CD-RISC-25). - Stress, anxiety, and depression (DASS-21). - Parental stress (PSI-4-SF). - Mindful attention (MAAS). - Life orientation (LOT-R). - Acceptance and action (AAQ-II). - Self-compassion (SCS). - Family empowerment (FES). - Marriage quality (QMI). - Strengths and difficulties (SDQ). - Social responsiveness (SRS-2). - Disruptive behaviour (ABC-2). |

| Sutherland et al. (2025) [38] | Examine the experiences of participants and facilitators in a systematic family support programme, and the processes involved in the perceived changes. | 8 parents (mainly mothers) and 9 family facilitators trained for the programme. Children aged 8 to 13 years old with ASD or intellectual disability. | Qualitative study evaluating processes and experiences, based on semi-structured interviews and focus groups, with thematic analysis applied to the participants’ and facilitators’ experiences and perspectives after the intervention. | - Semi-structured interviews. |

| Yu et al. (2025) [39] | Evaluate feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of family intervention aimed at promoting health and wellbeing. | 30 parents (mostly mothers) of children with intellectual disability and developmental difficulties, aged 6 to 17 years old. Hispanic families, with cultural and linguistic barriers to accessing services, in the United States. | Pilot study of intervention with a mixed approach. Pre-post evaluation. | - Self-efficacy in health (Self-Rated Abilities for Health Practices). - Social support (MSPSS). - Dietary behaviour (NCI Dietary Screener). - Physical activity (CHAMPS and PAQ-C). - Quality of life (PROMIS). - Index of unhealthy eating, screen time, depression, and stress (CESD-10, PSS-10). - Body mass index (BMI). |

| Authors (Year) | Intervention Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (2023) [4] | Short online intervention, 4 weeks, asynchronous (allowing access to the programme in line with participants’ other day to day commitments). Weekly modules lasting about 12 min (weekly reminders to finish modules): (1) Psychoeducation in self-compassion, (2) self-kindness, (3) shared humanity, and (4) mindfulness. Each module includes short psychoeducation about the topic being dealt with and a written experiential activity adapted to reflect parental experiences. Various activities: reflection exercises, writing about painful parenting events, and practices to promote self-compassion, self-kindness, recognition of shared humanity, and mindfulness. |

| Bergman et al. (2023) [26] | Group coping intervention based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT Navigator) 5 group sessions each lasting 3.5 h and 1 reinforcement session lasting 2.5 h: (1) Where am I? Parenting a child with a disability; psychoeducation about parental stress, grief, the importance of rest; coping strategies; acceptance as an alternative to control and avoidance. (2) What is important for me? Impact of language on suffering; healthy distance from internal experiences; mindfulness in everyday tasks, play, and activity; valuable areas of life; accepting the child; self-compassion. (3) What can hold me back? Working on values: “Navigator for parenting and life”; identifying and managing internal and external barriers; unwritten rules that act as barriers; triggers in challenging parenting situations. (4) What do I need to do? The observer’s perspective and changing perspective; mindfulness and experiential acceptance in difficult situations; committed action that matters. (5) What do I promise myself? Creating an energetic balance: changing or accepting daily activities; engaging with parenting values; self-care; mindfulness in pleasant situations; self-compassion; psychologically flexible parenting. Closed groups of between 8 and 16 parents. Actively experiential methods: exercises, metaphor, dramatization, imaginary presentations, psychoeducation, mindfulness |

| Boule et al. (2023) [27] | Early Positive Approaches to Support (E-PAtS). Group intervention lasting 8 weeks involving psychoeducational strategies and emotional support, with weekly 2–2.5 h group sessions in-person or online: (1) how to deal with available support and services, (2) parental self-care, (3) sleep, (4) communication, (5) adaptive behaviours, (6 & 7) challenging behaviours, and (8) close and reflection. Intervention co-implemented by a mental-health specialist and a trained parent. Use of emotion journals to record and reflect on parents’ own emotions before and after each session. |

| Buyuk & Ozmen (2025) [28] | Parental empowerment programme in two parts: (1) training in empowerment for parents (4 in-person group sessions lasting 45 min each), and (2) motivational interviews (2 individual sessions). The topics addressed include the importance of play and communication, problems and managing them in nutrition, sleep, safety, self-care, and strategies for coping with parental stress. The sessions used interactive methods: structured presentations, guided discussion, and question and answer sessions. The motivational interview was performed by a certified researcher to ensure adherence and competence. |

| Fante et al. (2025) [29] | Mainly clinical intervention, but with activity in the home agreed with the family, based on TEACCH. Involving specialists from different areas (clinical psychologists, paediatricians, child neuropsychologists, speech therapists) in constant collaboration with the families. Variable duration, with individual, weekly 2–4 h sessions (the number of sessions is not specified: ongoing intervention). Parental training with an emphasis on active parental participation in all stages of diagnosis and rehabilitation, active collaboration between parents and specialists, parental training, psychological support, and generalisation of learning in the home. Topics: personalised TEACCH strategies, behavioural management, developing skills, parental and family support, training and support, social inclusion. |

| Gore et al. (2022) [30] | Early Positive Approaches to Support (E-PAtS). Group intervention, co-facilitated by a specialist and a family carer to offer early support to families. 8 weekly sessions lasting about two and a half hours, with groups of between 4 and 8 families. Combines practical exercises, group discussions, and psychoeducation. Subjects covered: access to services and training in assertiveness skills; carer’s wellbeing, promoting self-care and emotion management; helping the child sleep; communication and interaction with the child; development of adaptive skills; managing challenging behaviour (2 session); and incorporating knowledge and planning for the future. |

| Ibrahim et al. (2025) [31] | Community intervention based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), with a strong parental participation component in 2 different directions: intervention for children and intervention for parents. The intervention for parents offers 3 possible formats: (1) 9 weekly forty-five-minute sessions, (2) 18 thirty-minute sessions, or (3) 2 two-hour sessions spaced each three weeks for 9 weeks. Regardless of format, the program begins with a 2-h informative session. Online version is available (applied during the COVID-19 pandemic). |

| Ingersoll et al. (2024) [32] | ImPACT Online: parent-mediated intervention programme, based on the Naturalistic–Developmental–Behavioural Intervention (NDBI). 2 possible formats: (1) Self-directed (over 6 months, 12 online interactive readings each lasting 75 min, depending on the pace of each participant). The readings cover: benefits of parent-mediated intervention, social communication, preparing the home for success, and other strategies (concentrating on the child, tailoring communication, creating opportunities, teaching new habits, and modelling interaction). (2) Self-directed + remote assistance from a therapist (includes 24 thirty-minute remote coaching sessions over 6 months: 2 sessions per week provided by a clinical specialist). |

| Lodder et al. (2020) [20] | Psychosocial intervention protecting against stigma (SOLACE programme). Eight weeks of weekly sessions (hybrid format: in-person sessions (1, 4, and 8) and online (2, 3, 5, 6, and 7)). The programme is based on psychoeducational strategies, cognitive restructuring, and techniques centred on compassion for reducing internalisation of stigma and protecting parents’ mental health. It includes group activities, discussion, and shared experiences to encourage identification with other parents and social support. Topics covered: myths and stereotypes about autism, managing stigma, positive meaning in care, resilience, self-esteem, social support, self-care and acceptance, as well as strategies for dealing with automatic negative thoughts related to stigma. |

| Ondrušková et al. (2023) [33] | Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP) programme, parent-mediated. A psychoeducational programme based on the social learning model, comprising 6 in-person group sessions lasting 2.5 h and 3 individual thirty-minute calls over 9 weeks, given by trained therapists. Teaches behavioural strategies and management strategies to improve parents’ confidence and reduce challenging behaviours, promoting a positive parent–child relationship. |

| Proctor et al. (2024) [34] | Parental intervention programme with a group approach for reinforcing parenting skills. 8 group sessions lasting 2 h each. Uses a participative methodology where the facilitators guide, but the parents share and direct. Focus: parent empowerment and self-efficacy; peer support, connection between families facing similar challenges; social inclusion; sharing knowledge about resources, rights, and wellbeing related to disabilities; defensive skills and being advocates of children with disabilities; others such as health and community integration. |

| Safer-Lichtenstein et al. (2023) [35] | 2 parental interventions (initially in-person but due to COVID-19, an online format was adopted): - Psychoeducation, stress reduction and mindfulness (MBSR). - Behavioural training for parents (BPT). 10 group support sessions, each lasting about 90 min, weekly over 10 weeks. Psychoeducation content + parental behavioural training or + mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques (MBSR). |

| Schelbusch et al. (2024) [36] | The Well-Beans for Caregivers programme (an adaptation of a wellbeing module for carers from the WHO Caregiver Skills Training (CST) programme). 3 in-person group sessions each lasting 2 h, over 3 weeks: - Session 1: introduction to acceptance and commitment, with emphasis on identifying personal values and the importance of accepting difficult emotions; activities to learn to be present and observe thoughts without judgement. - Session 2: techniques for coping with stressful thoughts and feelings related to caring for the child; exercises to improve psychological flexibility and manage emotional stress. Session 3: reinforcing commitment with actions in line with identified values; strategies for self-care, and construction of social support networks that strengthen resilience. The intervention is facilitated by a tiered model of training and supervision that includes mental health specialists and non-specialists. It is based on Acceptance and Commitment Theory (ACT). The sessions include stories, live exercises, and group discussions to help carers manage stress and improve their mental wellbeing. Strategies are applied to facilitate understanding, accessibility, and cultural adaptation, such as simplified language, use of illustrations, and the possibility of mixing local idioms with English. |

| Schwartzman et al. (2021) [37] | AMOR programme (Acceptance, Mindfulness, Optimism, Resilience Method). Facilitated by specialists in psychology 8 weekly group sessions lasting about 90 min each, which combine teaching, group discussion, behavioural practice, and weekly homework. Meditation exercises, reviewing homework, teaching new resilience strategies based on cognitive-behavioural therapy, full attention, self-compassion, and optimistic thinking. Content: managing stress, changing mentality about stress, gratitude, mindfulness, acceptance, facing grief and loss, optimism (in two sessions), self-compassion, and review to prioritise resilience. |

| Sutherland et al. (2025) [38] | Positive Family Connections Programme. Facilitated by trained family carers, supervised by psychologists. 6 online group sessions lasting 2 h with groups of 6–8 families (up to 2 carers per family). Topics covered: strengthening family relationships and wellbeing through peer support and promotion of healthy family processes. |

| Yu et al. (2025) [39] | Family PODER: an intervention culturally adapted for Latin American families. 10 weekly virtual individual sessions with a trained promotor, each lasting about 1 h, plus 3 group sessions reinforcing the content, two in-person and one virtual as an adaptation to overcome logistical obstacles. Individual session content: wellbeing and managing stress; balanced nutrition and food preparation; social support and healthy decision-making. The group sessions involve interactive activities to reinforce the learning, including practical demonstrations. |

| Intervention | Aspects Addressed to Improve Socio-Emotional Wellbeing | Main Related Results | Effectiveness (%) | Adherence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (2023) [4] | - Self-compassion - Emotional wellbeing | - Reduced parental stress - Increased self-compassion | ~60–65% | >80% |

| Bergman et al. (2023) [26] | - Parental stress - Self-care | - Improved emotional acceptance - Reduced parental stress | >70% | 80–85% |

| Boule et al. (2023) [27] | - Parental self-care - Communication | - Improved self-care - Improved family life | 65–75% | >75% |

| Buyuk & Ozmen (2025) [28] | - Stress management - Communication - Empowerments | - Increased parental self-efficacy - Reduced stress | 70% | 70–75% |

| Fante et al. (2025) [29] | - Behavioural management - Social abilities | - Reduction in disruptive behaviours - Improved social skills | >70% | 75–80% |

| Gore et al. (2022) [30] | - Self-care - Adaptive skills | - Improved access to services - Promoted self-care - Improved adaptive skills | 65–70% | >70% |

| Ibrahim et al. (2025) [31] | - Stress - Parenting skills | - Improved parenting abilities - Improved stress management | >70% | 70–80% |

| Ingersoll et al. (2024) [32] | - Social communication - Behavioural management | - Improved social communication - Reduction in disruptive behaviours | 75–85% | 80% |

| Lodder et al. (2020) [20] | - Resilience - Stigma - Social support | - Increased resilience - Reduced stigma - Improved social support | 65–70% | 70% |

| Ondrušková et al. (2023) [33] | - Behavioural management - Parenting strategies | - Improved parenting strategies - Improved confidence | 70–80% | >75% |

| Proctor et al. (2024) [34] | - Empowerment - Peer support | - Strengthened active participation - Strengthened social networks - Benefits in defensive skills | 65–70% | 75% |

| Safer-Lichtenstein et al. (2023) [35] | - Stress - Emotional wellbeing | - Reduced parental stress | >70% | 70–75% |

| Schelbusch et al. (2024) [36] | - Self-care - Resilience | - Increased resilience - Reduced anxiety | 70% | 80% |

| Schwartzman et al. (2021) [37] | - Social support - Family wellbeing | - Strengthened social support - Strengthened family wellbeing | 65–70% | 75% |

| Sutherland et al. (2025) [38] | - Coping - Resilience | - Improved emotional wellbeing | 70–80% | 80–85% |

| Yu et al. (2025) [39] | - Stress - Emotional wellbeing - Parent empowerment - Social support | - Improved stress management | 70–75% | 70–75% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Álvarez-Fernández, M.L.; Rodríguez, C. Socio-Emotional Wellbeing in Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Children 2026, 13, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010099

Álvarez-Fernández ML, Rodríguez C. Socio-Emotional Wellbeing in Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Children. 2026; 13(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁlvarez-Fernández, Mª Lourdes, and Celestino Rodríguez. 2026. "Socio-Emotional Wellbeing in Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review" Children 13, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010099

APA StyleÁlvarez-Fernández, M. L., & Rodríguez, C. (2026). Socio-Emotional Wellbeing in Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Children, 13(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010099