Laparoscopic Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Without a Peel-Away Sheath in Children: A Comparison with Conventional Open Surgery

Highlights

- Laparoscopy-assisted VPS insertion without a peel-away sheath in children shows outcomes comparable to conventional open surgery.

- In cases with prior abdominal surgery, laparoscopy allows safe catheter placement by avoiding or lysing adhesions.

- Laparoscopic VPS insertion without a peel-away sheath is a safe and effective surgical option in pediatric patients.

- Particularly in revisions or patients with previous operations, it may help reduce adhesion-related shunt failure, although further studies are warranted.

Abstract

1. Introduction

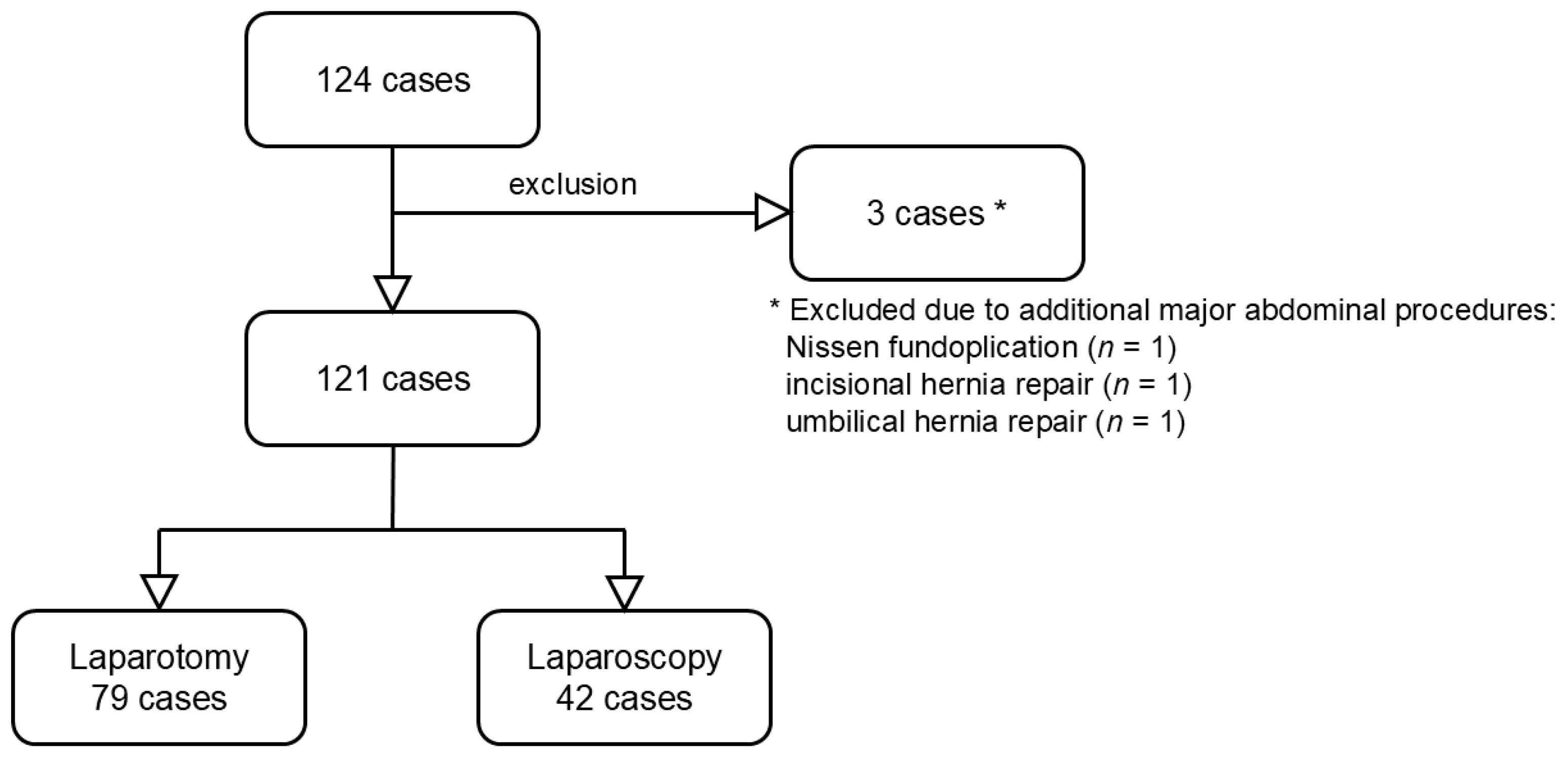

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.3. Operation Procedure

2.3.1. Laparotomy

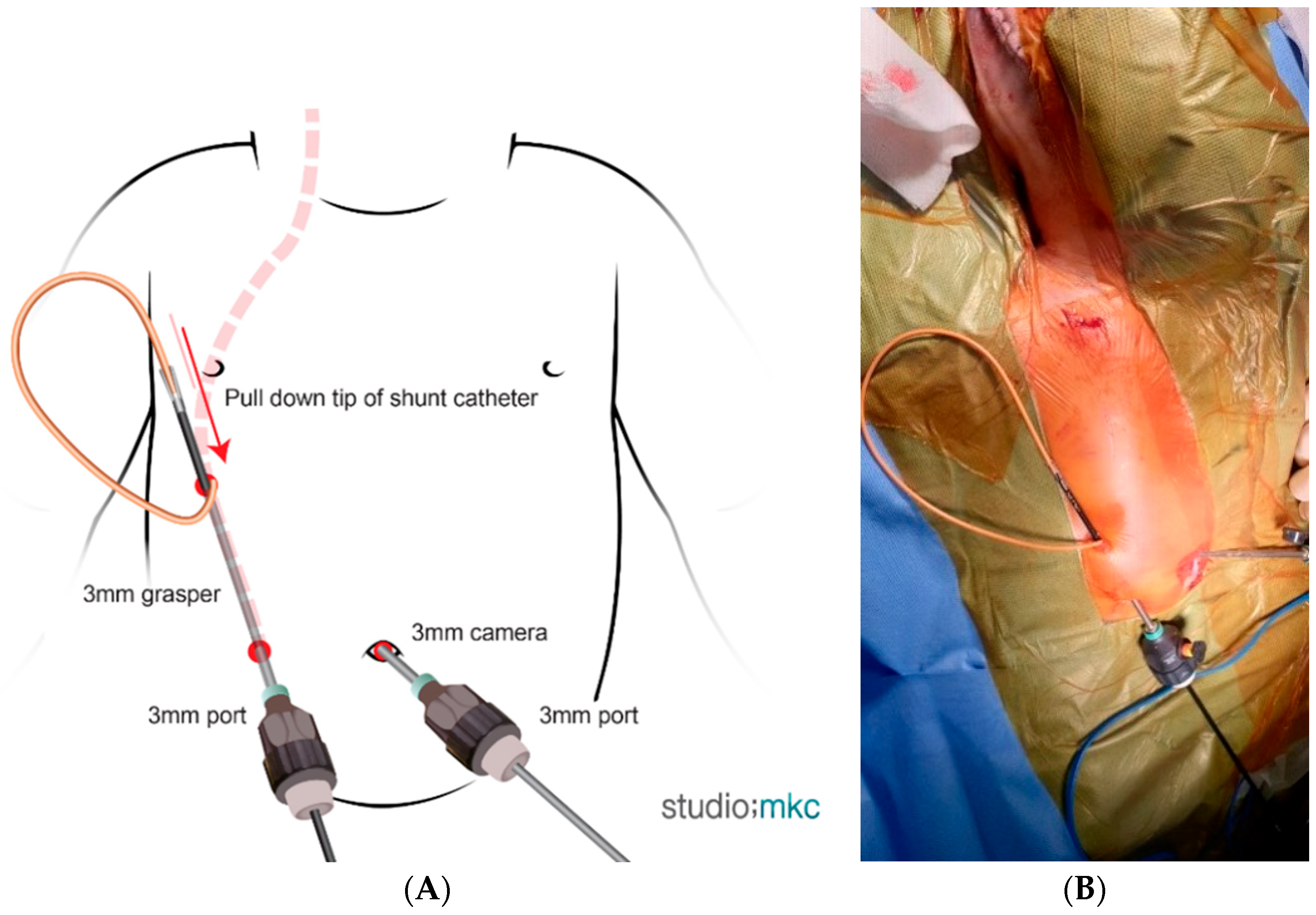

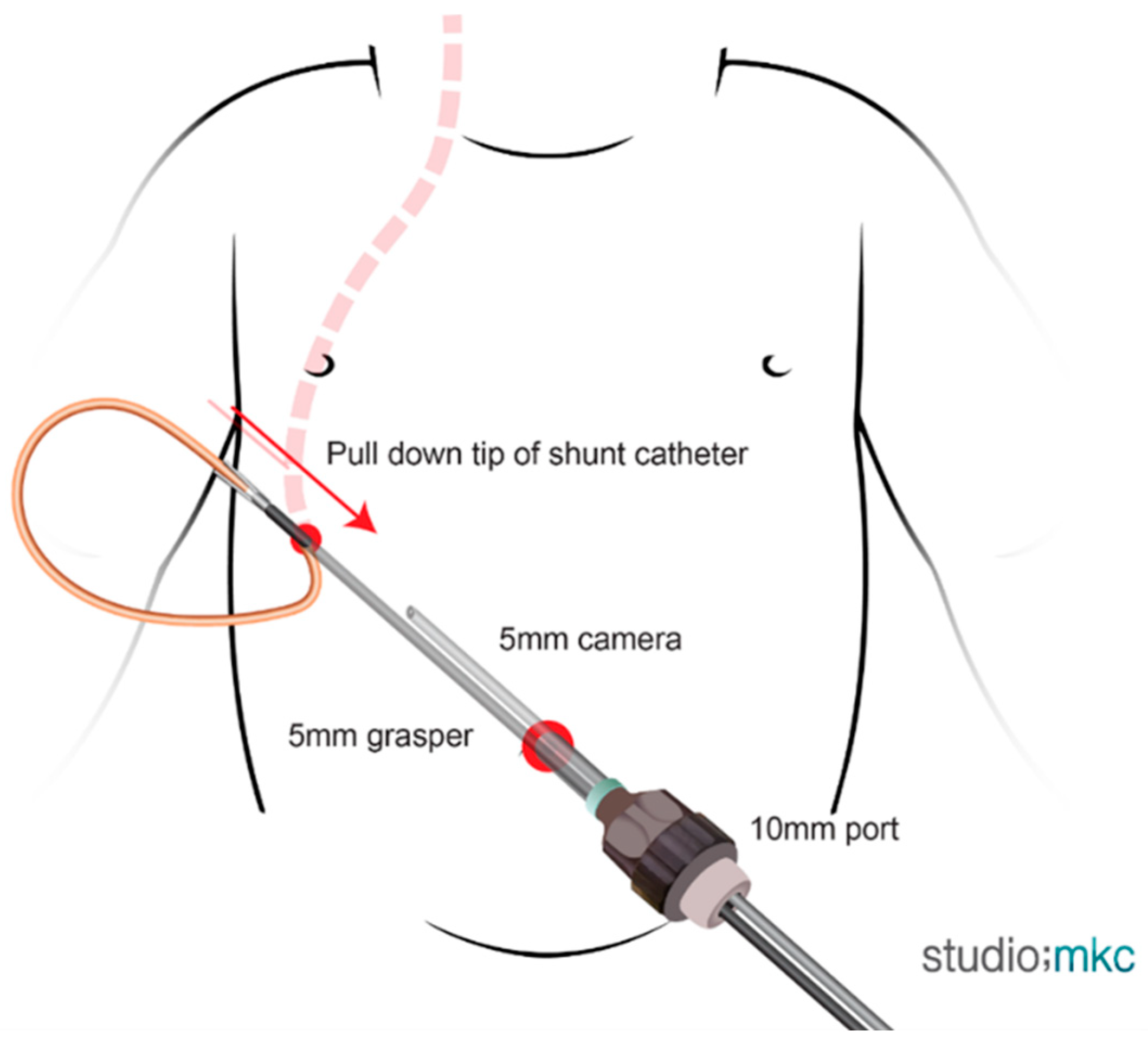

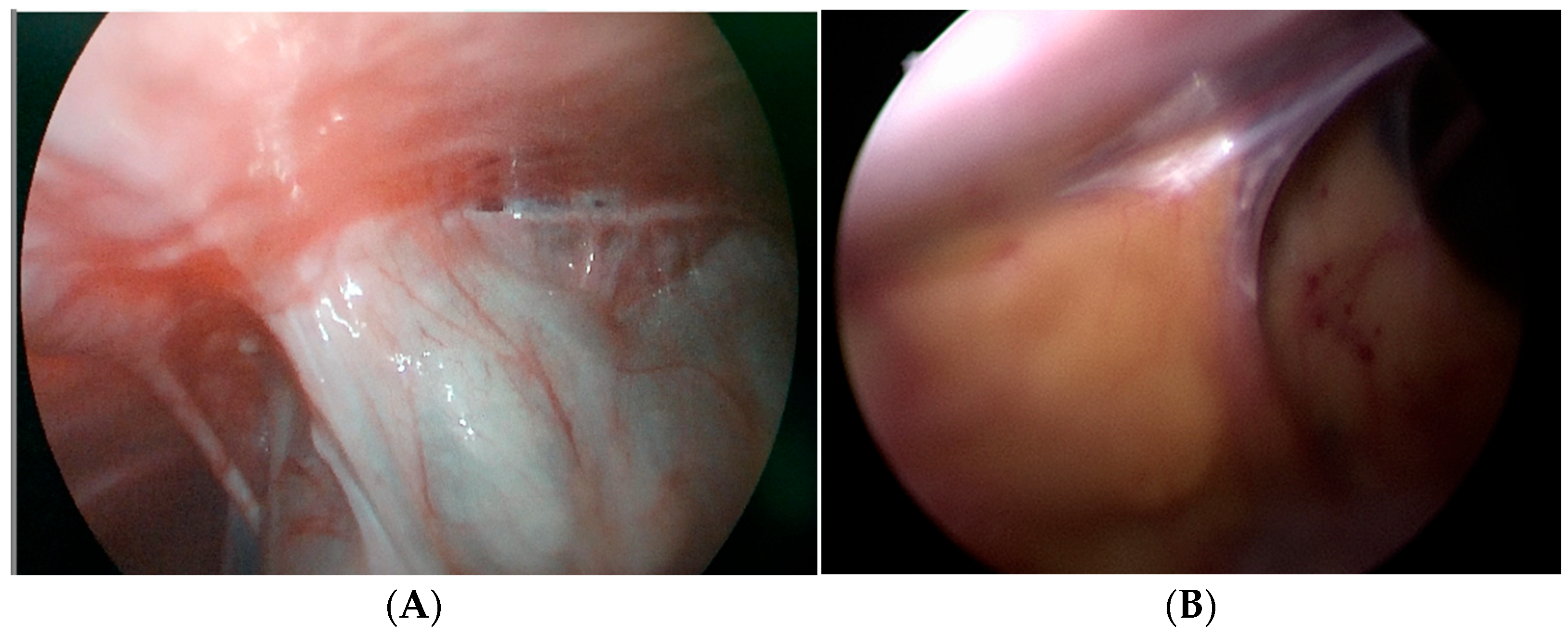

2.3.2. Laparoscopy

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

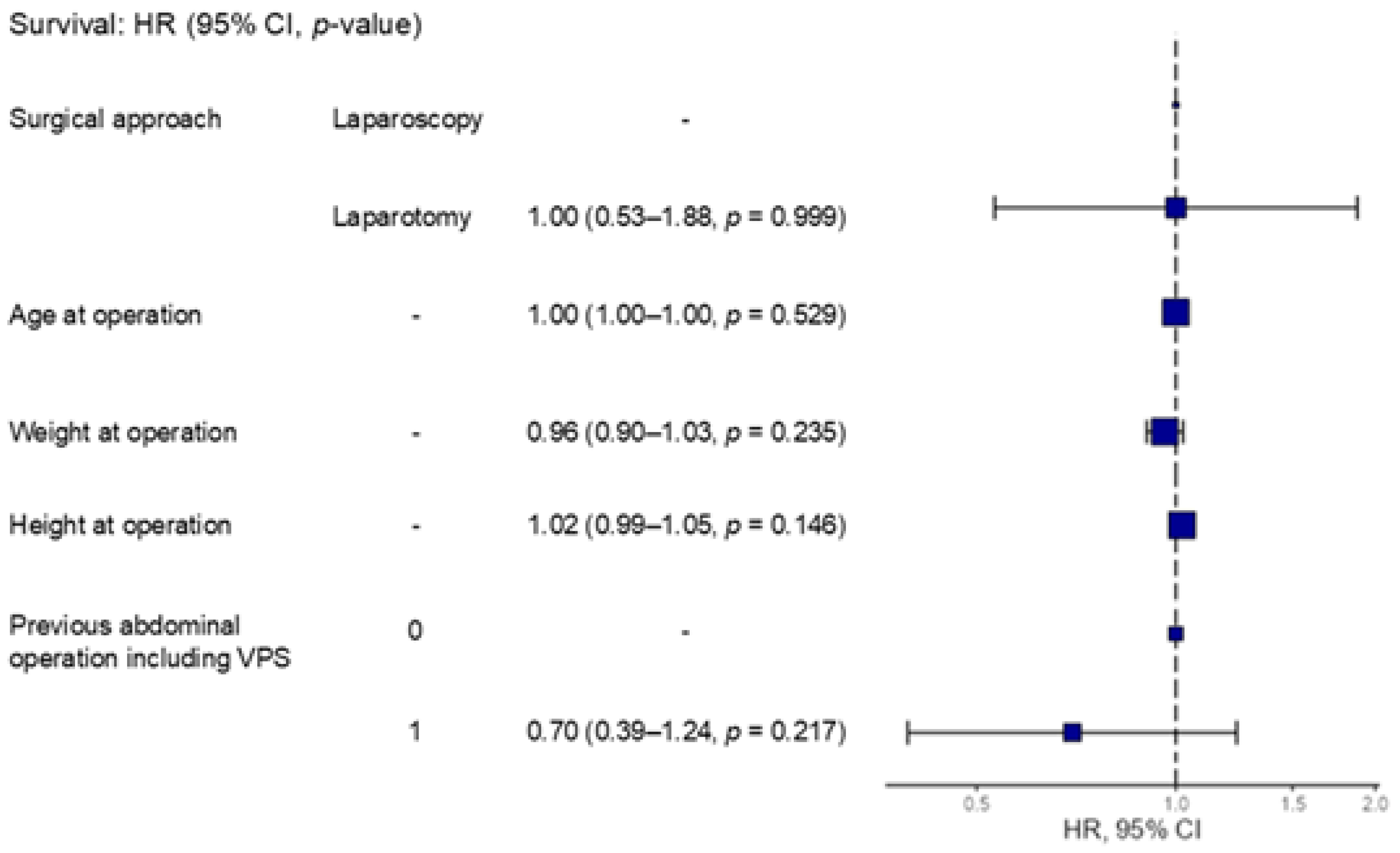

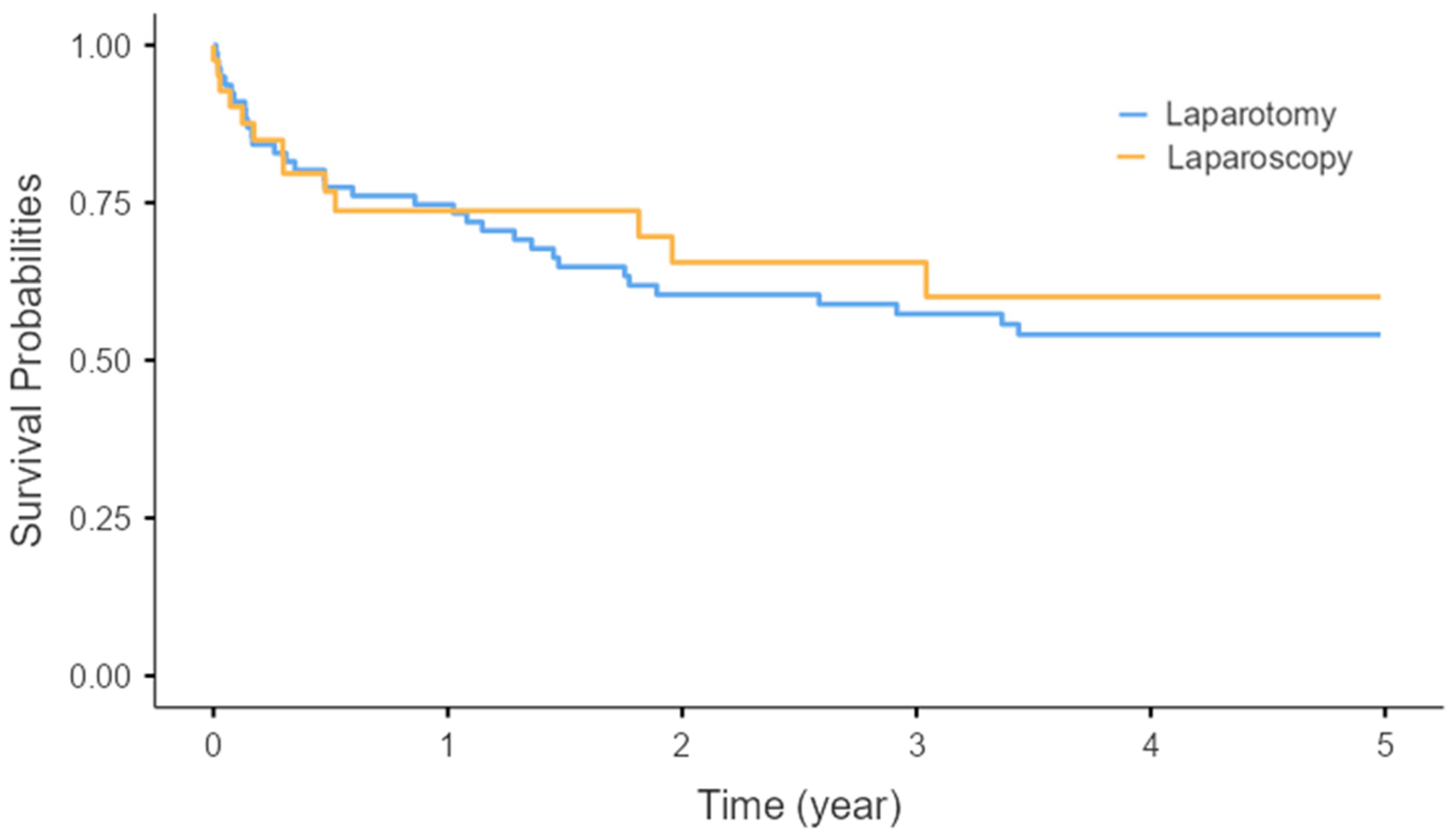

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| VPS | Ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

References

- Kahle, K.T.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Limbrick, D.D., Jr.; Warf, B.C. Hydrocephalus in children. Lancet 2016, 387, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.; Blauensteiner, J.; Ammerer, H.P.; Kriwanek, S. Laparoscopically assisted implantation of ventriculoperito-neal shunts. J. Laparoendosc. Surg. 1993, 3, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopacinski, A.B.; Guy, K.M.; Burgess, J.R.; Collins, J.N. Differences in Outcome Between Open vs Laparoscopic Insertion of Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva-Cambrin, J.; Kestle, J.R.; Holubkov, R.; Butler, J.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Drake, J.; Whitehead, W.E.; Wellons, J.C., 3rd; Shannon, C.N.; Tamber, M.S.; et al. Risk factors for shunt malfunction in pe-diatric hydrocephalus: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2016, 17, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.W.; Pimpalwar, A. Laparoscopic-assisted placement of ventriculo-peritoneal shunt tips in children with multi-ple previous open abdominal ventriculo-peritoneal shunt surgeries. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 19, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A.G.; Sisson, W.B.; Gonda, D.D.; Kling, K.M.; Ignacio, R.C.; Thangarajah, H.; Bickler, S.W.; Levy, M.L.; Lazar, D.A. Just Stick a Scope in: Laparoscopic Ven-triculoperitoneal Shunt Placement in the Pediatric Reoperative Abdomen. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 269, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftel, R.P.; Argo, J.L.; Shannon, C.N.; Taylor, T.H.; Tubbs, R.S.; Clements, R.H.; Harrigan, M.R. Laparoscopic versus open insertion of the peritoneal catheter in ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: Review of 810 consecutive cases. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, L.; Ruf, L.; Guzman, R.; Soleman, J. Open versus laparoscopic ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2023, 39, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argo, J.L.; Yellumahanthi, D.K.; Ballem, N.; Harrigan, M.R.; Fisher, W.S., 3rd; Wesley, M.M.; Taylor, T.H.; Clements, R.H. Laparoscopic versus open ap-proach for implantation of the peritoneal catheter during ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. Surg. Endosc. 2009, 23, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handler, M.H.; Callahan, B. Laparoscopic placement of distal ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheters. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2008, 2, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiblawi, R.; Zoeller, C.; Zanini, A.; Kuebler, J.F.; Dingemann, C.; Ure, B.; Schukfeh, N. Laparoscopic versus Open Pediatric Surgery: Three Decades of Comparative Studies. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 32, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, F.; Bortot, G.; Gnech, M.; Contini, G.; Escolino, M.; Esposito, C.; Capozza, N.; Berrettini, A.; Masieri, L.; Castagnetti, M. Comparison of Cosmetic Results in Children > 10 Years Old Undergoing Open, Laparoscopic or Robotic-Assisted Pyeloplasty: A Multicentric Study. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysi Dehcordi, S.; De Tommasi, C.; Ricci, A.; Marzi, S.; Ruscitti, C.; Amicucci, G.; Galzio, R.J. Laparoscopy-assisted ventriculoperi-toneal shunt surgery: Personal experience and review of the literature. Neurosurg. Rev. 2011, 34, 363–370; discussion 70-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, M.T. Laparoscopic Intervention after Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: A Case Report, Systematic Review, and Recommendations. World J. Laparosc. Surg. 2020, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, S.; Liao, J.; Jia, F.; Maharaj, M.; Reddy, R.; Mobbs, R.J.; Rao, P.J.; Phan, K. Laparotomy vs minimally invasive laparoscopic ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement for hydrocephalus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 140, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lower, A.M.; Hawthorn, R.J.S.; Emeritus, H.E.; O’BRien, F.; Buchan, S.; Crowe, A.M. The impact of adhesions on hospital readmissions over ten years after 8849 open gynaecological operations: An assessment from the Surgical and Clinical Adhesions Re-search Study. BJOG 2000, 107, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, J.E.; Wilson, S.E.; Nguyen, N.T. Laparoscopic surgery significantly reduces surgical-site infections compared with open surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverkamp, M.P.; de Roos, M.A.J.; Ong, K.H. The ERAS protocol reduces the length of stay after laparoscopic colectomies. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Gupta, B.; Johansen, P.; Santiago, R.B.; Dabecco, R.; Mandel, M.; Adada, B.; Botero, J.; Roy, M.; Borghei-Razavi, H. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Pa-tients with Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Undergoing Ventriculoperitoneal Shunting Procedures. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2023, 230, 107757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.A.; Beierle, E.A.; Chen, M.K. Role of laparoscopy in the prevention and in the treatment of adhesions. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 23, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokoma, N.J.M.; Hassett, S.M.; Tsang, T.T.F. Trocar site adhesions after laparoscopic surgery in children. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2009, 19, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laparotomy (n = 79) | Laparoscopy (n = 42) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (week) | 31.73 ± 7.51 | 32.67 ± 5.52 | 0.487 |

| Gender (M/F) | 43 (54.6%)/36 (45.6%) | 24 (57%)/18 (43%) | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 2.05 ± 1.04 | 2.07 ± 1.08 | 0.904 |

| Age (day) at operation | 1036.52 ± 1414.89 (7 days–16 years) | 1795.98 ± 1514.87 (14 days–13 years) | 0.007 |

| Weight (kg) at operation | 11.83 ± 11.66 (1.8–58.9) | 17.06 ± 12.09 (2.6–50.7) | 0.022 |

| Height (cm) at operation | 77.63 ± 30.64 (43–173) | 95.01 ± 32.08 (44–155) | 0.004 |

| Laparotomy (n = 79) | Laparoscopy (n = 42) | Total (n = 121) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage induced | 37 (46.8%) | 28 (66.7%) | 65 (53.7%) |

| Tumorous condition induced | 7 (8.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | 8 (6.6%) |

| Congenital anomaly related | 16 (20.3%) | 6 (14.3%) | 22 (18.2%) |

| Infectious condition related | 7 (8.9%) | 4 (9.5%) | 11 (9.1%) |

| Hypoxia-induced encephalopathy related | 7 (8.9%) | 0 | 7 (5.8%) |

| Unknown origin | 5 (6.3%) | 3 (7.1%) | 8 (6.6%) |

| Laparotomy (n = 79) | Laparoscopy (n = 42) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of VPS insertion | 0.035 | ||

| Primary | 46 (58.2%) | 16 (38.1%) | |

| 2nd | 27 (34.2%) | 12 (28.6%) | |

| 3rd | 5 (6.3%) | 9 (21.4%) | |

| More than 3rd time | 1 (1.3%) | 5 (11.9%) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery except previous VPS insertion | 0.978 | ||

| Yes | 12 (15.2%) | 7 (16.7%) | |

| No | 67 (84.8%) | 35 (83.3%) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery include previous VPS insertion | 0.009 | ||

| Yes | 37 (46.8%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| No | 42 (53.2%) | 12 (28.6%) | |

| Laparotomy (n = 79) | Laparoscopy (n = 42) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall OP time (min) | 73.61 ± 26.98 (30–175) | 69.16 ± 35.63 (15–200) | 0.443 |

| Distal catheter insertion time (min) | 34.06 ± 20.48 (10–120) | 31.79 ± 22.14 (5–140) | 0.572 |

| Overall OP time excluding adhesiolysis cases (min) † | 73.78 ± 27.11 (30–175) | 70.53 ± 36.28 (30–200) | 0.589 |

| Distal catheter insertion time excluding adhesiolysis cases (min) † | 33.92 ± 20.57 (10–120) | 30.53 ± 22.08 (5–140) | 0.417 |

| Intraoperative complication | 0 | 0 | |

| Recognition of adhesion | 3 (3.8%) | 22 (52.4%) | <0.001 |

| Adhesiolysis | 1 (1.3%) | 4 (9.5%) | <0.001 |

| Inserting away from adhesion | 0 | 9 (21.4%) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization (day) | 19.73 ± 28.3 (2–166) | 8.05 ± 7.57 (0–36) | <0.001 |

| Diet start (day) | 0.53 ± 0.73 (0–3) | 0.24 ± 0.43 (0–1) | 0.006 |

| Laparotomy (n = 79) | Laparoscopy (n = 42) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malfunction | |||

| Proximal | 9 (29.0%) | 2 (20%) | 0.581 |

| Distal | 15 (48.4%) | 4 (40%) | 0.647 |

| Unknown | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (10%) | 0.978 |

| Infection † | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (30%) | 0.119 |

| Pseudocyst | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.572 |

| Total failure | 31 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 0.090 |

| VPS related death † | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0.656 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ryu, M.; Kang, A.; Kim, S.-H.; Chung, J.H.; Hong, H.; Sung, S.-K. Laparoscopic Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Without a Peel-Away Sheath in Children: A Comparison with Conventional Open Surgery. Children 2026, 13, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010072

Ryu M, Kang A, Kim S-H, Chung JH, Hong H, Sung S-K. Laparoscopic Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Without a Peel-Away Sheath in Children: A Comparison with Conventional Open Surgery. Children. 2026; 13(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyu, Miri, Ayoung Kang, Soo-Hong Kim, Jae Hun Chung, Hanpyo Hong, and Soon-Ki Sung. 2026. "Laparoscopic Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Without a Peel-Away Sheath in Children: A Comparison with Conventional Open Surgery" Children 13, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010072

APA StyleRyu, M., Kang, A., Kim, S.-H., Chung, J. H., Hong, H., & Sung, S.-K. (2026). Laparoscopic Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Insertion Without a Peel-Away Sheath in Children: A Comparison with Conventional Open Surgery. Children, 13(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010072