Parathyroidectomy in the Treatment of Childhood Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Institution Experience

Highlights

- Hyperparathyroidism is rarely seen in childhood, and parathyroidectomy plays a crucial role in its treatment.

- There are very few studies in the literature that present the surgical outcomes of primary, secondary, and tertiary hyperparathyroidism cases together.

- Childhood parathyroidectomy is successfully performed in experienced institutions.

- Successful parathyroidectomy results are presented by comprehensively addressing all groups of childhood hyperparathyroidism.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

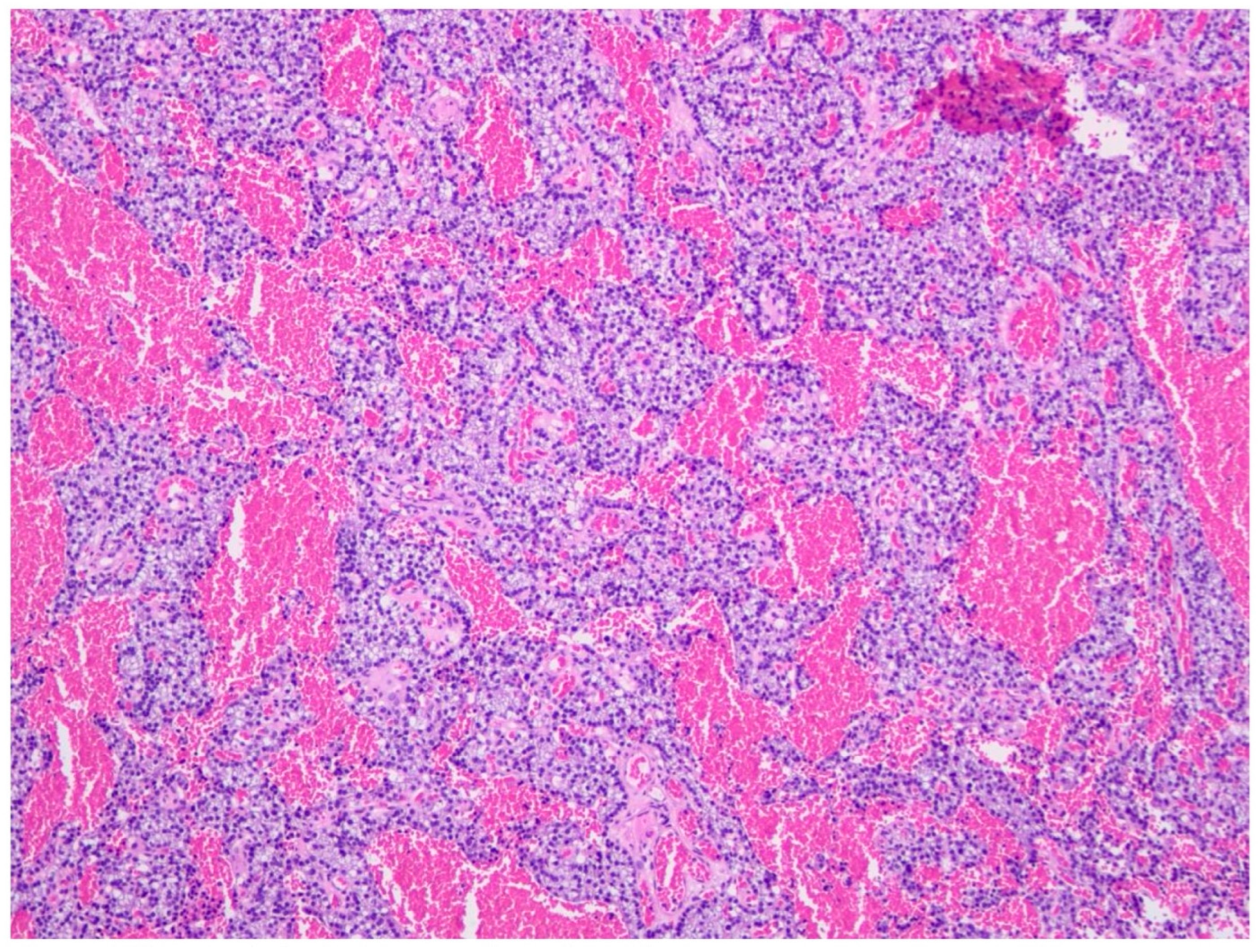

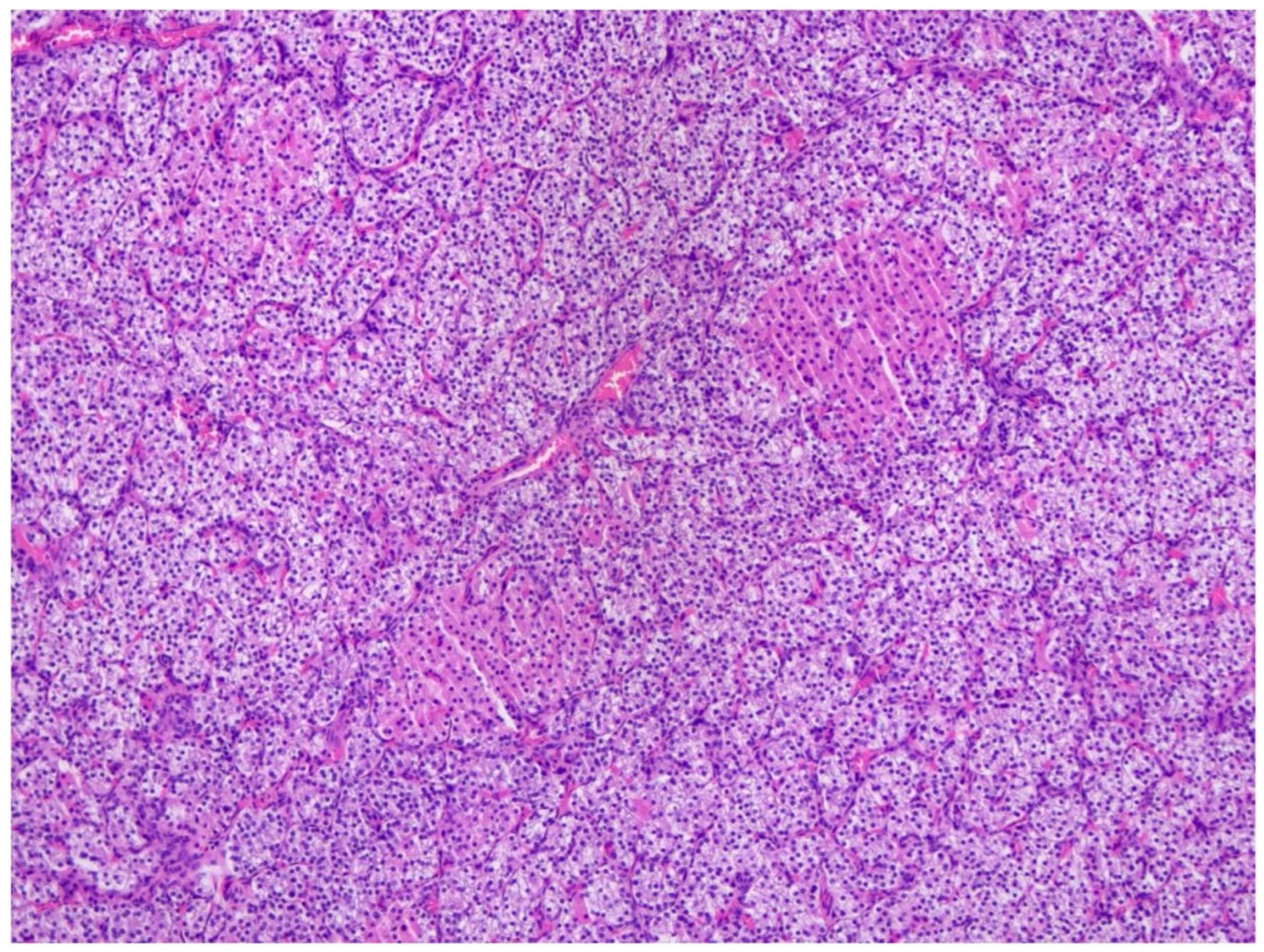

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics, Etiology, Clinical Presentation, and Diagnosis

4.2. Biochemical Profiles in Pediatric HPT

4.3. Preoperative Imaging and Intraoperative Localization/Monitoring

4.4. Management, Complications, and Outcomes of Ptx in Pediatric Hpt

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BNE | Bilateral neck exploration |

| CRF | Chronic renal failure |

| HBS | Hungry bone syndrome |

| HPT | Hyperparathyroidism |

| Io-PTH | Intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring |

| MIP | Minimally invasive parathyroidectomy |

| pHPT | Primary hyperparathyroidism |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| PTX | Parathyroidectomy |

| r-HPT | Renal hyperparathyroidism |

| S-CT | Single-photon emission computed tomography |

| sHPT | Secondary hyperparathyroidism |

| S-mibi | Tc 99 sestamibi scintigraphy |

| tHPT | Tertiary hyperparathyroidism |

| US | Ultrasonography |

| W/FNA | Washout/Fine needle aspiration biopsy |

References

- Singh Ospina, N.M.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, R.; Maraka, S.; Espinosa de Ycaza, A.E.; Jasim, S.; Castaneda-Guarderas, A.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Al Nofal, A.; Brito, J.P.; Erwin, P.; et al. Outcomes of Parathyroidectomy in Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 2359–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Skorecki, K.; Green, J.; Brenner, M.M. Chronic Renal Failure. In Harrison’s Principles of Medicine, 15th ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1551–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, G.E. Uremia. In Textbook of Nephrology, 2nd ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1989; pp. 540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, E.T.; Nichol, P.F.; Lund, D.P.; Chen, H.; Sippel, R.S. What is the optimal treatment for children with primary hyperparathyroidism? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, K.; Schmitt, C.P.; Bartholomaeus, J.E.; Suchan, K.L.; Buchler, M.W.; Rothmund, M.; Weber, T. Parathyroidectomy for renal hyperparathyroidism in children and adolescents. World J. Surg. 2008, 32, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roztczyńska, D.; Konturek, A.; Wędrychowicz, A.; Ossowska, M.; Kapusta, A.; Taczanowska-Niemczuk, A.; Starzyk, J.B. Long-Term Consequences of Misdiagnosis of Parathyroid Adenomas in Pediatric Patients. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2025, 2025, 2390925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, H.A. Clinical insight into hypercalcemia in children. Endokrynol. Pol. 2025, 76, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo Yamashita, T.; Gudmundsdottir, H.; Foster, T.R.; Lyden, M.L.; Dy, B.M.; Tebben, P.J.; McKenzie, T. Pediatric primary hyperparathyroidism: Surgical pathology and long-term outcomes in sporadic and familial cases. Am. J. Surg. 2023, 225, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, J.F.; Chen, H.; Gosain, A. Parathyroid conditions in childhood. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 23, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roizen, J.; Levine, M.A. A meta-analysis comparing the biochemistry of primary hyperparathyroidism in youths to the biochemistry of primary hyperparathyroidism in adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 4555–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griebeler, M.L.; Kearns, A.E.; Ryu, E.; Hathcock, M.A.; Melton, L.J.; Wermers, R.A., 3rd. Secular trends in the incidence of primary hyperparathyroidism over five decades (1965–2010). Bone 2015, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharanappa, V.; Mishra, A.; Bhatia, V.; Mayilvagnan, S.; Chand, G.; Agarwal, G.; Agarwal, A.; Mishra, S.K. Pediatric Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Experience in a Tertiary Care Referral Center in a Developing Country Over Three Decades. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 488–495. [Google Scholar]

- Cetani, F.; Dinoi, E.; Pierotti, L.; Pardi, E. Familial states of primary hyperparathyroidism: An update. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 2157–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salameh, A.; Haissaguerre, M.; Tresallet, C.; Kuczma, P.; Marciniak, C.; Cardot-Bauters, C. Chapter 6: Syndromic primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann. Endocrinol. 2025, 86, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanet, P.; Coppin, L.; Molin, A.; Santucci, N.; Le Bras, M.; Odou, M.F. Chapter 5: The roles of genetics in primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann. Endocrinol. 2025, 86, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migon, J.; Miciak, M.; Pupka, D.; Biernat, S.; Nowak, L.; Kaliszewski, K. Analysis of Clinical and Biochemical Parameters and the Effectiveness of Surgical Treatment in Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Center Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla, E.E.; Levine, M.A.; Adzick, N.S. Outcomes of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy in pediatric patients with primary hyperparathyroidism owing to parathyroid adenoma: A single institution experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 52, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langusch, C.C.; Norlen, O.; Titmuss, A.; Donoghue, K.; Holland, A.J.; Shun, A.; Delbridge, L. Focused image-guided parathyroidectomy in the current management of primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollars, J.; Zarroug, A.E.; van Heerden, J.; Lteif, A.; Stavlo, P.; Suarez, L.; Moir, C.; Ishitani, M.; Rodeberg, D. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pediatric patients. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kievit, A.J.; Tinnemans, J.G.; Idu, M.M.; Groothoff, J.W.; Surachno, S.; Aronson, D.C. Outcome of total parathyroidectomy and autotransplantation as treatment of secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism in children and adults. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygun, N.; Uludag, M. Surgical Treatment of Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Which Therapy to Whom? Med. Bull. Sisli Hosp. 2019, 53, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyer, T.; Karnak, I.; Tuncel, M.; Ekinci, S.; Andiran, F.; Ciftci, A.O.; Akcoren, Z.; Orhan, D.; Alikasifoglu, A.; Ozon, A.; et al. Results of intraoperative gamma probe survey and frozen section in surgical treatment of parathyroid adenoma in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 51, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Luo, Y.; Jin, S.; Wang, O.; Liao, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, H. Can we skip technetium-99 m sestamibi scintigraphy in pediatric primary hyperparathyroidism patients with positive neck ultrasound results? Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, 2253–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unlu, M.T.; Kostek, M.; Caliskan, O.; Sekban, T.A.; Aygun, N.; Uludag, M. The Relationship of Negative Imaging Result and Surgical Success Rate in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Sisli Etfal Hastan. Tip. Bul. 2023, 57, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Kong, X.R.; Ouyang, J. A 10-year retrospective study of primary hyperparathyroidism in children. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2012, 120, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Min, E.A.; Hwang, Y.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Yi, J.W. Single-Center Experience of Parathyroidectomy Using Intraoperative Parathyroid Hormone Monitoring. Medicina 2022, 58, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.R.; Lobos, P.A.; Moldes, J.M.; Liberto, D.H. Usefulness of combined ultrasonography and scintigraphy in the preoperative assessment of secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Cir. Pediatr. 2021, 34, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Medas, F.; Cappellacci, F.; Canu, G.L.; Noordzij, J.P.; Erdas, E.; Calo, P.G. The role of Rapid Intraoperative Parathyroid Hormone (ioPTH) assay in determining outcome of parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 92, 106042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, O.; Otgun, I.; Yalcin Comert, H.; Gencoglu, A.; Baskin, E. Effectiveness of the Gamma Probe in Childhood Parathyroidectomy: Retrospective Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.; Erbil, Y.; Ersoz, F.; Olmez, A.; Salmaslioglu, A.; Adalet, I.; Colak, N.; Ozarmagan, S. Radio-guided excision of parathyroid lesions in patients who had previous neck surgeries: A safe and easy technique for re-operative parathyroid surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2011, 9, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.J.; Sullivan, B.T.; Duke, W.S.; Terris, D.J. Routine bilateral neck exploration and four-gland dissection remains unnecessary in modern parathyroid surgery. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramonell, K.M.; Fazendin, J.; Lovell, K.; Iyer, P.; Chen, H.; Lindeman, B.; Dream, S. Outpatient parathyroidectomy in the pediatric population: An 18-year experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Nakajima, H.; Mori, J.; Fukuhara, S.; Shigehara, K.; Adachi, S.; Hosoi, H. Decrement in bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy in a pediatric patient with primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2018, 27, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, R.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Wu, G. Subtotal parathyroidectomy versus total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation for secondary hyperparathyroidism: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2019, 404, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.R.; Aboueisha, M.A.; Attia, A.S.; Omar, M.; ELnahla, A.; Toraih, E.A.; Shama, M.; Chung, W.Y.; Jeong, J.J.; Kandil, E. Outcomes of Subtotal Parathyroidectomy Versus Total Parathyroidectomy with Autotransplantation for Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism: Multi-institutional Study. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, R.M.; Richardson, A.J.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Woods, C.G.; Oliver, D.O.; Morris, P.J. Total parathyroidectomy alone or with autograft for renal hyperparathyroidism? Q. J. Med. 1991, 79, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glassford, D.M.; Remmers, A.R.; Sarles, H.E., Jr.; Lindley, J.D.; Scurry, M.T.; Fish, J.C. Hyperparathyroidism in the maintenance dialysis patient. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1976, 142, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kakani, E.; Sloan, D.; Sawaya, B.P.; El-Husseini, A.; Malluche, H.H.; Rao, M. Long-term outcomes and management considerations after parathyroidectomy in the dialysis patient. Semin. Dial. 2019, 32, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanba, C.; Bobian, M.; Svider, P.F.; Sheyn, A.; Siegel, B.; Lin, H.S.; Raza, S.N. Perioperative considerations and complications in pediatric parathyroidectomy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 91, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pHPT (n = 6) | r-HPT (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 15 ± 3.1 | 13 ± 4.4 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Female | 3 (50%) | 4 (100%) |

| Symptom Duration (months) (Mean ± SD) | 10.8 ± 7.5 | 96 ± 46 |

| System-related Symptoms | ||

| Neuropsychiatric | ||

| Headache | 3 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 0 |

| Irritability | 2 | 0 |

| Forgetfulness | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0 |

| Seizures | 0 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Abdominal pain | 4 | 0 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 1 | 0 |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 | 0 |

| Weight gain | 1 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Leg pain/Burning | 4 | 1 |

| Cramping/Spasms | 2 | 0 |

| Walking difficulty | 0 | 2 |

| Bone deformities (X-bone) | 0 | 2 |

| Fractures | 0 | 2 |

| Urinary | ||

| Nephrolithiasis | 1 | 0 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 0 | 4 |

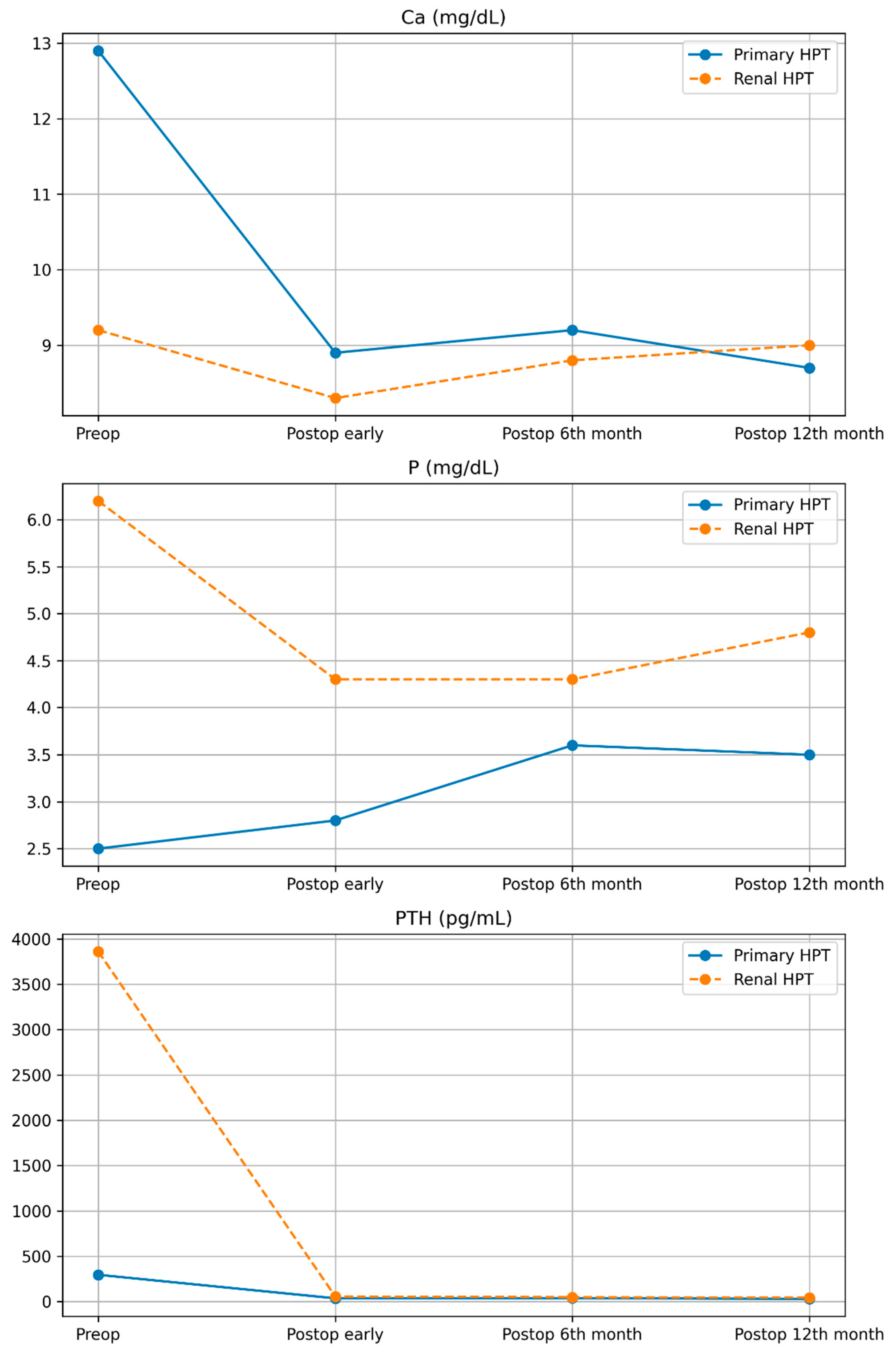

| Variable (Mean ± SD) | pHPT (n = 6) | r-HPT (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca, mg/dL) | ||

| Preoperative | 12.9 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.9 |

| Postoperative (Early) | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.5 |

| Postoperative (6 months) | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.7 |

| Postoperative (12 months) | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 9 ± 0.9 |

| Phosphorus (P, mg/dL) | ||

| Preoperative | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 1.5 |

| Postoperative (Early) | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 1.3 |

| Postoperative (6 months) | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 1.3 |

| Postoperative (12 months) | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 1.1 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | ||

| Preoperative | 259.5 ± 276.7 | 3861.5 ± 1336.7 |

| Postoperative (Early) | 36.5 ± 12.1 | 57 ± 44.9 |

| Postoperative (6 months) | 49.5 ± 8.7 | 38 ± 28.9 |

| Postoperative (12 months) | 44.8 ± 5.5 | 30.5 ± 23.8 |

| Specimen Weight (mg), n | 480 ± 147.57 | 453.1 ± 549.416 |

| Specimen Volume (mm3) | 417.5 ± 234.9 | 512.1 ± 464.3 |

| Hospital Stay (days) | 2 ± 0 | 11 ± 2.7 |

| Follow-up Period (months) | 50 ± 32.6 | 22.5 ± 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ozaydin, S.; Sari, S.; Aytac Kaplan, E.H.; Kocabey Sutcu, Z.; Yavuz, S.; Barut, H.Y.; Karatay, H.; Esen Akkas, B. Parathyroidectomy in the Treatment of Childhood Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Institution Experience. Children 2026, 13, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010064

Ozaydin S, Sari S, Aytac Kaplan EH, Kocabey Sutcu Z, Yavuz S, Barut HY, Karatay H, Esen Akkas B. Parathyroidectomy in the Treatment of Childhood Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Institution Experience. Children. 2026; 13(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzaydin, Seyithan, Serkan Sari, Emel Hatun Aytac Kaplan, Zumrut Kocabey Sutcu, Sevgi Yavuz, Hamit Yucel Barut, Huseyin Karatay, and Burcu Esen Akkas. 2026. "Parathyroidectomy in the Treatment of Childhood Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Institution Experience" Children 13, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010064

APA StyleOzaydin, S., Sari, S., Aytac Kaplan, E. H., Kocabey Sutcu, Z., Yavuz, S., Barut, H. Y., Karatay, H., & Esen Akkas, B. (2026). Parathyroidectomy in the Treatment of Childhood Hyperparathyroidism: A Single-Institution Experience. Children, 13(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010064