1. Introduction

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a rare congenital anomaly resulting from incomplete esophageal development during foregut embryogenesis. It has an estimated incidence of 1 in 3500 live births and is commonly associated with one or both pouches connecting to the trachea, a condition called tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). Embryologically, the esophagus develops from the foregut, and disturbances in longitudinal growth or foregut separation may result in a spectrum of anatomical configurations [

1]. The most widely used classification system, proposed by Gross, describes five anatomical types (

Table 1) [

2].

Among these, type A (7–8% of cases) is characterized by two esophageal pouches typically widely separated, with the proximal pouch ending in the upper thorax and the distal pouch in the lower mediastinum. This substantial gap often required staged surgical approaches, including thoracoscopy, gastrostomy, delayed primary anastomosis, esophageal replacement techniques, or esophageal lengthening procedures such as the Foker process [

3,

4,

5].

Furthermore, accurate preoperative identification of the esophageal pouches remains challenging, especially in neonates. While radiographic findings—such as absence of intra-abdominal gas—strongly suggest type A EA, they offer limited insight into pouch length or location. This often necessitates intraoperative exploration to determine the most appropriate surgical approach.

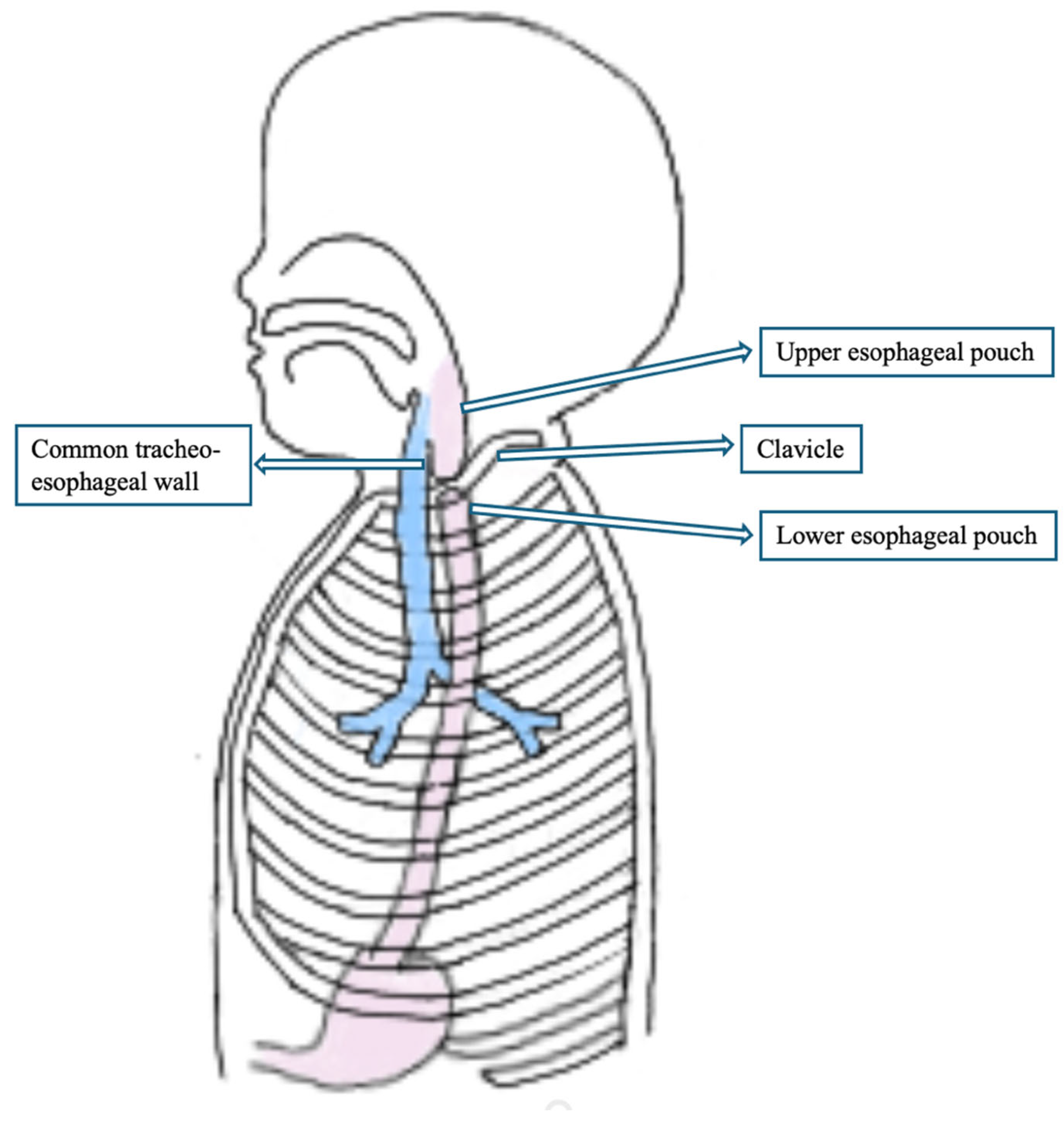

We present a unique case of type A EA in which both esophageal pouches were ultimately found to be in the cervical region, an unexpected finding revealed during thoracoscopic exploration, which initially showed the distal pouch extending cranially to the thoracic inlet. The patient, after thoracoscopic exploration underwent to a successful primary anastomosis through a cervical approach. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of type A EA with both esophageal pouches located in the neck, representing a rare anatomical variant with implications for diagnosis and surgical management.

2. Case Report

A male 36 + 3/40 gestational age newborn, birth weight 3136 g, was naturally delivered in a district general hospital due to severe polyhydramnios (AFI: 35 cm). Prenatal ultrasound had shown severe polyhydramnios without evidence of gastric bubble, raising suspicion for esophageal atresia. No other congenital anomalies were detected during prenatal screening. A preoperative bronchoscopy was performed prior to the gastrostomy in order to rule out a proximal tracheoesophageal fistula. The procedure confirmed the absence of a fistula and revealed no signs of tracheomalacia.

At birth, the baby presented with excessive salivation. Attempts to pass a nasogastric (NG) tube were unsuccessful beyond 9 cm at the lips, indicating an obstruction. The tube was left in place at that level, and a babygram obtained with gentle downward pressure showed the tube coiled in the upper mediastinum and absence of intra-abdominal gas, consistent with esophageal atresia type A (

Figure 1).

Based on initial radiographic findings suggestive of a long-gap EA, a gastrostomy was performed on the first day of life to ensure enteral nutrition while planning for delayed primary repair. The patient was scheduled for thoracoscopic assessment after 15 days to evaluate the esophageal gap and determine the need for traction techniques or other staged approaches. However, intraoperative findings revealed that the esophageal segments were in close proximity and both located in the cervical region, allowing for immediate primary anastomosis via a cervical approach.

Due to the radiological findings, a conventional pathway for this patient was enrolled; on the first day of life, the patient underwent gastrostomy placement to allow enteral feeding while awaiting delayed primary anastomosis. The x-ray study performed through gastrostomy showed very shorth distal pouch ending at the level nearly above the diaphragm.

After 15 days, the patient was taken to the operating room for thoracoscopic exploration. Unexpectedly, a regular distal esophageal pouch was visualized, extending cranially up above the thoracic inlet and appearing to reach the cervical region (

Figure 2).

The thoracoscopic assessment was performed with the aim of measuring the esophageal gap and evaluating the feasibility of primary anastomosis or internal traction with delayed primary anastomosis. However, intraoperative visualization of the distal esophagus extending into the thoracic inlet prompted reconsideration of the surgical plan (

Figure 3).

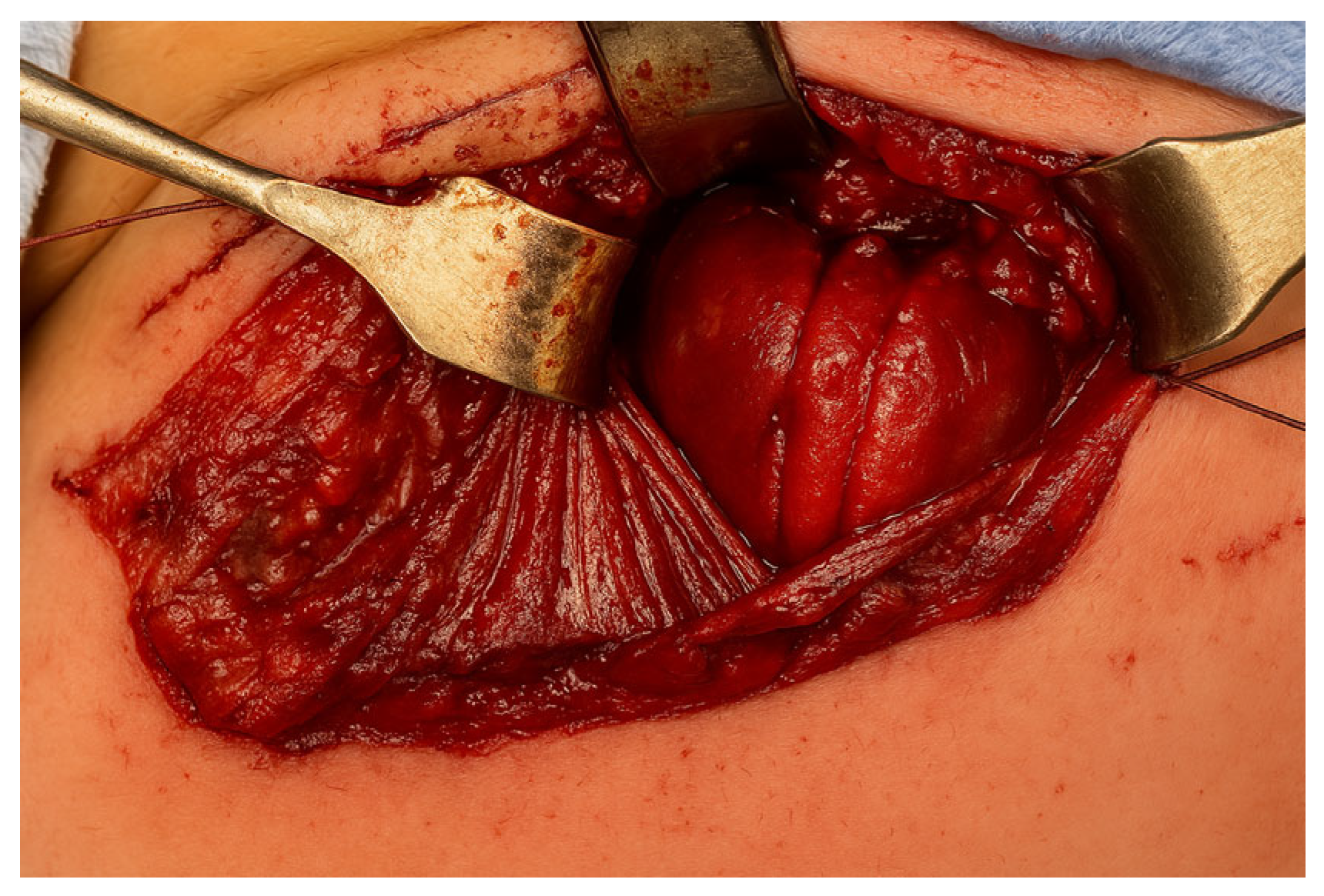

Therefore, a stay suture was placed at the most cranial portion of the distal esophageal stump, which was identified at the clavicular level, entirely outside the thoracic district. Although thoracoscopy revealed the proximity of the two esophageal ends, the anastomotic site was located extremely cranially, near the thoracic inlet. The confined space at that level made it technically unfeasible to safely place sutures via thoracoscopy. Therefore, a cervical approach was preferred to ensure optimal exposure and minimize the risk of complications.

A right-sided cervicotomy was performed, through which both the proximal and distal esophageal pouches were identified very close together. Therefore, a primary end-to-end anastomosis was successfully performed without tension using interrupted absorbable sutures (

Figure 4).

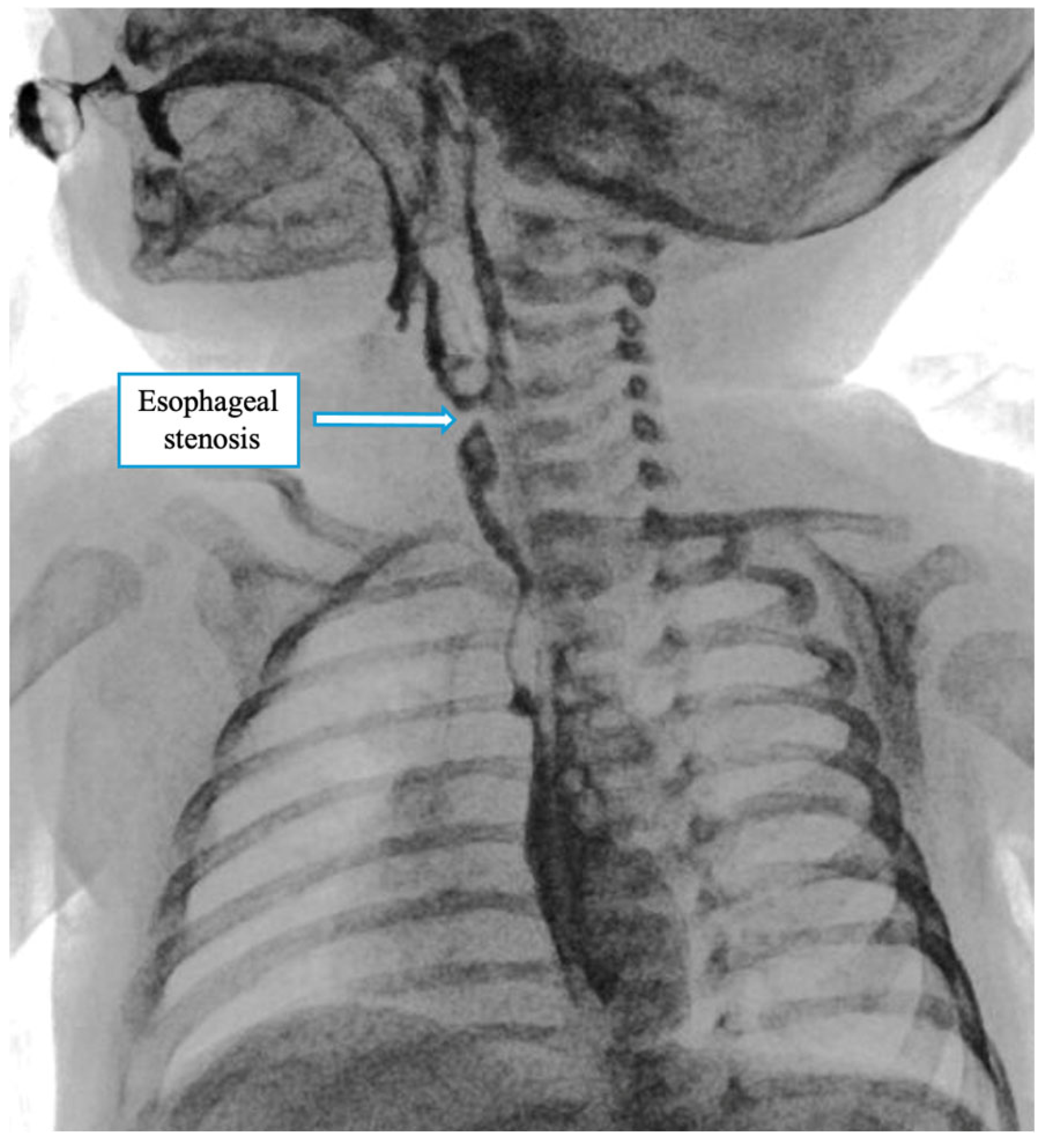

A contrast X-ray performed on postoperative day VII showed stenosis at the anastomotic site (

Figure 5). The patient underwent serial esophageal dilations (10 session) up to a caliber of 10 mm, and until clinical stability and good tolerability of oral feeding were achieved. During this period, oral intake improved gradually, and by the end of the third month, the patient had achieved stable, full oral feeding. At the latest follow-up at 6 months of age, the child was tolerating an age-appropriate oral diet without feeding-related difficulties, and growth parameters were within the normal range.

3. Discussion

Esophageal atresia (EA) type A, characterized by the absence of a tracheoesophageal fistula, presents significant surgical challenges due to the typically wide gap between the proximal and distal esophageal segments. In most cases, the upper pouch ends in the upper thoracic cavity. At the same time, the distal segment lies deep in the posterior mediastinum, making primary anastomosis technically difficult. The case presented deviates significantly from this classic anatomical pattern, with both esophageal segments located in the cervical region and in proximity, permitting a primary repair through a cervicotomy. This represents the first documented instance of such an anatomical variant in Gross type A EA.

Kemmotsu et al. presented the cervical approach for cases of EA with TEF (type C) located in a high position emphasizing the role of bronchoscopy or contrasty study to detect the location of the distal pouch [

6,

7]. However it would be not helpful in our case as there was no fistula so eventual bronchoscopy would bring nothing to the diagnosis.

Also, Nakagawa et al. presented two case with EA type C approach by the neck, suggesting to perform the preoperative contrast examinations and bronchoscopy routinely to detect the location of the upper esophageal pouch and of the TEF [

8]. However, contrast studies are not routinely performed in type C EA. The diagnosis is usually made based on clinical signs and standard radiography. Bronchoscopy remains the key preoperative tool to locate the fistula and evaluate the anatomy. Contrast studies may be useful in selected cases, particularly when a high or cervical fistula is suspected or the anatomy is unclear.

Contrast study is suitable when EA associated with TEF while in our case it’s not possible estimate the length of the distal pouch because of the absence of the fistula. Although the contrast study through the gastrostomy suggested a very short distal pouch, this was misleading. The distal esophagus was extending cranially into the cervical region, as revealed during thoracoscopic exploration. This highlights the limitations of contrast studies in type A EA without fistula, where the true anatomy may not be accurately represented.

This unusual presentation may have important implications for both diagnosis and surgical strategy. In standard practice, preoperative imaging can provide valuable information about pouch location, although it may be limited in precisely identifying the extent of the distal esophagus, particularly in neonates. Despite typical radiological findings suggesting long-gap atresia, the proper anatomy only became evident during thoracoscopic exploration. The cranial course of the distal esophagus, extending into the cervical region, is highly atypical and not previously described in the literature. Identifying a typical distal pouch with cranial extension supports the hypothesis of a developmental arrest at a higher anatomical level than usual, possibly due to an aberration in the longitudinal growth or separation of the foregut during embryogenesis [

9]. Our case showed clear the advantage of thoracoscopic approach that was very helpful in correct diagnosis in atypical situation.

This rare anatomical variant highlights the need for intraoperative adaptability. While thoracoscopy remains the preferred diagnostic approach in such cases—thanks to its minimal invasiveness and superior visualization—esophageal continuity can also be assessed through an open procedure when necessary. In our case, thoracoscopy could not be continued due to the exceptionally high cervical location of the esophageal ends, which limited the operative space and prevented precise needle manipulation. Therefore, the procedure was converted to a cervical approach. Cervical anastomosis is generally associated with lower morbidity and facilitates easier postoperative management, including dilations. In our patient, the postoperative course was uneventful, with successful recovery of oral feeding following only a few sessions of esophageal dilation to address a mild anastomotic stricture. From a broader perspective, this case highlights the heterogeneity of EA anatomy and suggests that not all Gross type A cases should be assumed to have a long-gap configuration. In addition to its surgical relevance, this case may serve as a useful contribution to basic anatomical and developmental research. The presence of both esophageal pouches in the cervical region suggests a possible embryological arrest or deviation at a higher level than typically observed in type A EA. This observation supports further investigation into the developmental mechanisms underlying esophageal elongation and separation. From a diagnostic standpoint, the case also raises important considerations: in the absence of a tracheoesophageal fistula, the distal esophageal pouch is often not easily visualized, limiting the utility of preoperative contrast studies via gastrostomy. Although such studies might be attempted to estimate pouch length, their accuracy is questionable without a patent fistula. In these situations, thoracoscopic exploration remains the most reliable tool to assess anatomy and guide the surgical strategy.

4. Conclusions

This case describes a rare anatomical variant of Gross type A esophageal atresia, with both esophageal pouches in the cervical region, allowing for primary anastomosis via a cervical approach. While the cervical approach has been rarely described for esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula, its application in type A EA is unprecedented. It shows the advantage of thoracoscopy to precisely check the malformation anatomy. If thoracoscopy was performed as the first procedure it even would be possible to avoid gastrostomy and shortage the time of hospital stay. Improved preoperative assessment and early thoracoscopic exploration may help identify such rare anatomical variations, optimizing surgical outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.M.; validation, E.C., C.B., E.S. and F.T.; resources, A.D.C. and E.R.; data curation, M.D.M., R.L.P. and I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.M. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and D.P.; visualization, M.L., D.P. and M.M.; supervision, M.L., R.C. and R.L.P.; project administration, M.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The written informed consent from the parents of the patient for the submission of this case report was collected. Ethics approval was not sought for a single retrospective case report as per institutional practice.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article due to the nature of the case report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baldwin, D.L.; Yadav, D. Esophageal Atresia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560848/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Yang, S.; Yang, R.; Ma, X.; Yang, S.; Peng, Y.; Tao, Q.; Chen, K.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, J.; et al. Detail correction for Gross classification of esophageal atresia based on 434 cases in China. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 135, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadil, T.; Koivusalo, A.; Svensson, J.F.; Jönsson, L.; Lilja, H.E.; Thorup, J.M.; Sæter, T.; Stenström, P.; Qvist, N. Surgical treatment and major complications Within the first year of life in newborns with long-gap esophageal atresia gross type A and B—A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 2242–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borselle, D.; Davidson, J.; Loukogeorgakis, S.; De Coppi, P.; Patkowski, D. Thoracoscopic Stage Internal Traction Repair Reduces Time to Achieve Esophageal Continuity in Long Gap Esophageal Atresia. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 34, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairdain, S.; Hamilton, T.E.; Smithers, C.J.; Manfredi, M.; Ngo, P.; Gallagher, D.; Zurakowski, D.; Foker, J.E.; Jennings, R.W. Foker process for the correction of long gap esophageal atresia: Primary treatment versus secondary treatment after prior esophageal surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmotsu, H.; Joe, K.; Nakamura, H.; Yamashita, M. Cervical approach for the repair of esophageal atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1995, 30, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, W.D.; Freeman, J.K.; Martin, A.J. Supraclavicular approach to cervical esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1985, 20, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Uchida, H.; Shirota, C.; Tainaka, T.; Sumida, W.; Makita, S.; Amano, H.; Takimoto, A.; Ogata, S.; Takada, S.; et al. Preoperative Contrast Examinations Help Determine the Appropriate Cervical Approach for Congenital Gross Type C Esophageal Atresia: A Report of Two Cases. Am. J. Case Rep. 2023, 24, e938723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkin, N.; De Coppi, P. Anatomy and embryology of tracheo-esophageal fistula. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 31, 151231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).