Breaking the Cycle: Impact of Physical Activity on Sleep Disorders in Autism—A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

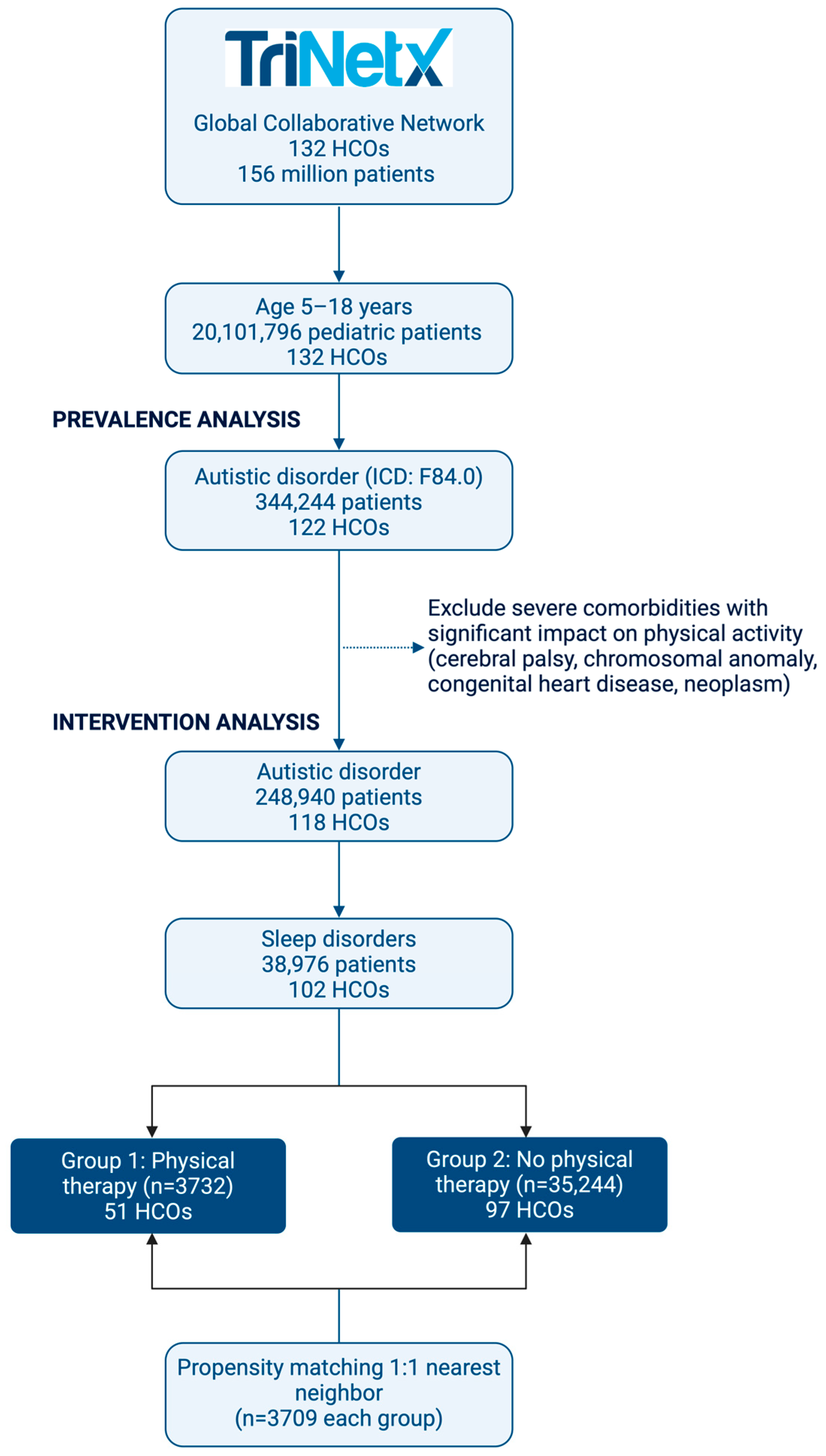

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Population and Design

2.3. Outcomes Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Sleep Disorders

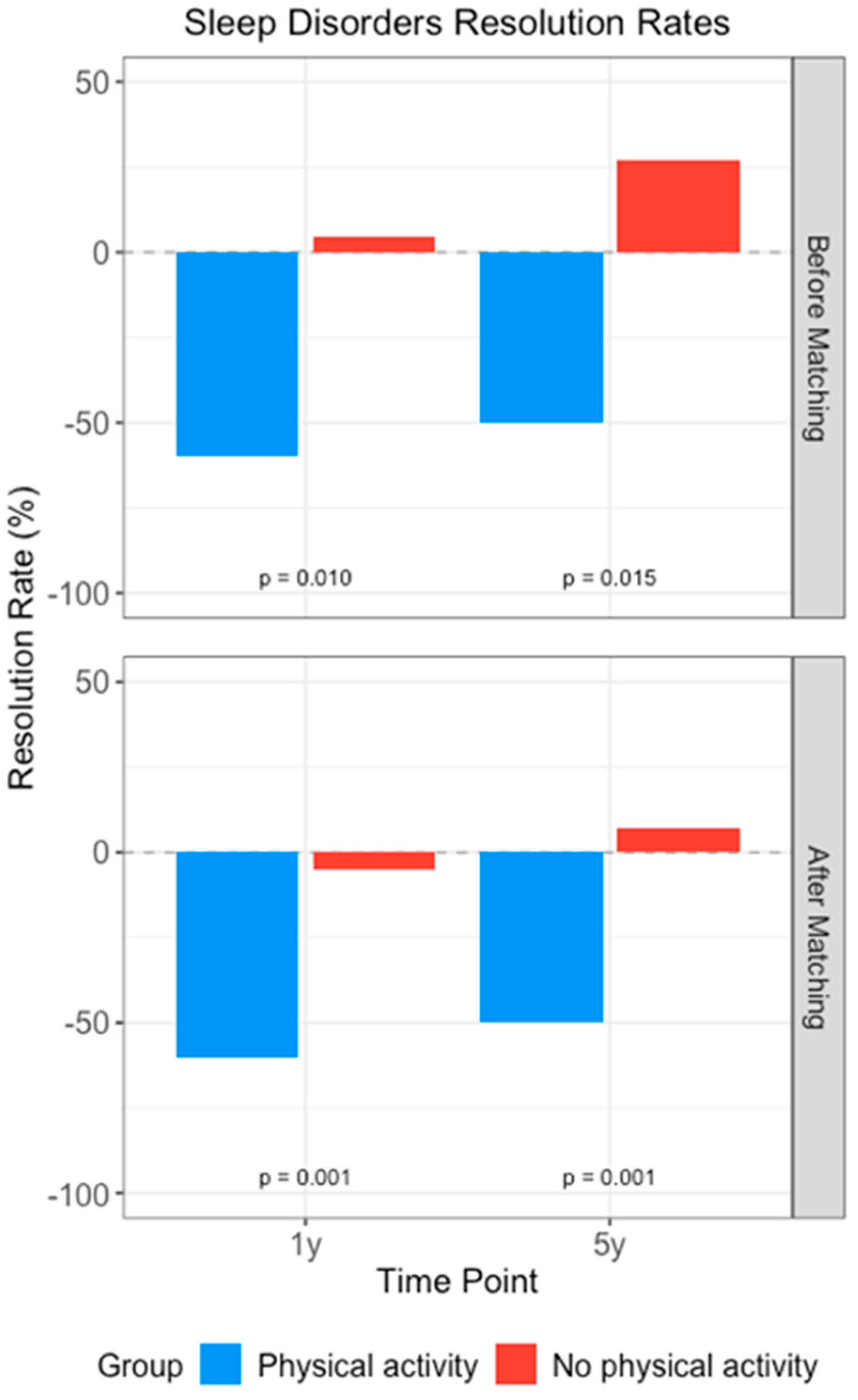

3.2. Impact of Physical Activity Intervention

3.3. Age-Stratified Analysis: Developmental Differences in Treatment Response

3.4. Nested Analysis by Comorbidity

3.5. Medication Utilization Changes

4. Discussion

4.1. Sleep Disorder Burden in Pediatric ASD Populations

4.2. Physical Activity Interventions and Sleep Outcomes

4.3. Age-Specific Response Patterns and Mechanisms

4.4. Sleep Disorder Subtype-Specific Responses

4.5. Proposed Biological Mechanisms

4.6. Psychiatric Comorbidity and Treatment Response

4.7. Medication Utilization Patterns and Clinical Implications

4.8. Implementation Challenges and Health Equity Considerations

4.9. Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

4.10. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xavier, S.D. The relationship between autism spectrum disorder and sleep. Sleep Sci. 2021, 14, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miano, S.; Bruni, O.; Elia, M.; Trovato, A.; Smerieri, A.; Verrillo, E.; Roccella, M.; Terzano, M.G.; Ferri, R. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder: A questionnaire and polysomnographic study. Sleep Med. 2007, 9, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.P.; Zarrinnegar, P. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Sleep. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 30, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwichtenberg, A.J.; Janis, A.; Lindsay, A.; Desai, H.; Sahu, A.; Kellerman, A.; Chong, P.L.H.; Abel, E.A.; Yatcilla, J.K. Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review and Systematic Update. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2022, 8, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Wang, F.; Angriman, M.; Masi, G.; Bruni, O. Sleep Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Management. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lv, Q.-K.; Xie, W.-Y.; Gong, S.-Y.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, J.-Y.; Mao, C.-J.; Liu, C.-F. Circadian disruption and sleep disorders in neurodegeneration. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souders, M.C.; Zavodny, S.; Eriksen, W.; Sinko, R.; Connell, J.; Kerns, C.; Schaaf, R.; Pinto-Martin, J. Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.; Belli, A.; Ferri, R.; Bruni, O. Sleeping without Prescription: Management of Sleep Disorders in Children with Autism with Non-Pharmacological Interventions and Over-the-Counter Treatments. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams Buckley, A.; Hirtz, D.; Oskoui, M.; Armstrong, M.J.; Batra, A.; Bridgemohan, C.; Coury, D.; Dawson, G.; Donley, D.; Findling, R.L.; et al. Practice guideline: Treatment for insomnia and disrupted sleep behavior in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2020, 94, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Tse, A.C.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.X. The impact of the physical activity intervention on sleep in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024, 74, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyar Iravanlou, F.; Soltani, M.; Alsadat Rahnemaei, F.; Abdi, F.; Ilkhani, M. Non-Pharmacological Approaches on the Improvement of Sleep Disturbances in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Iran. J. Child Neurol. 2021, 15, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, A.; Fang, Q.; Moosbrugger, M.E. Physical Activity Interventions for Improving Cognitive Functions in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Protocol for a Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e40383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, N.; Hosokawa, K. The importance of comprehensive support based on the three pillars of exercise, nutrition, and sleep for improving core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1119142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachob, D.; Lorenzi, D.G. Brief Report: Influence of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality in Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2641–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajszilber, D.; Santiseban, J.A.; Gruber, R. Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: Impact and management challenges. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Bixler, E.O.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Mahr, F.; Hillwig-Garcia, J.; Elamir, B.; Edhere-Ekezie, L.; Parvin, M. ADHD subtypes and comorbid anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder: Differences in sleep problems. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefen, J.A.N.; Al-Salmi, S.; Shaikh, Z.; AlMulhem, J.T.; Rajab, E.; Fredericks, S. Beneficial Use and Potential Effectiveness of Physical Activity in Managing Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 587560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, W.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H. The impact of the physical activity intervention on sleep in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1438786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, F.; Giannotti, F.; Ivanenko, A.; Johnson, K. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richdale, A.L.; Schreck, K.A. Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2009, 13, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.; Hoffman, C.D.; Sweeney, D.P.; Riggs, M.L. Relationship between children’s sleep and mental health in mothers of children with and without autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, S.E.; Richdale, A.L.; Clemons, T.; Malow, B.A. Parental sleep concerns in autism spectrum disorders: Variations from childhood to adolescence. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, M.O.; Petroski, G.F. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: Examining the contributions of sensory over-responsivity and anxiety. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.; Vieira, P.; Gomes, A.A.; Roth, T.; de Azevedo, M.H.P.; Marques, D.R. Sleep difficulties and use of prescription and non-prescription sleep aids in Portuguese higher education students. Sleep Epidemiol. 2021, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.; Pickles, A.; Lord, C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malow, B.A.; Katz, T.; Reynolds, A.M.; Shui, A.; Carno, M.; Connolly, H.V.; Coury, D.; Bennett, A.E. Sleep Difficulties and Medications in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Registry Study. Pediatrics 2016, 137, S98–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, V.; Orecchio, S.; Cameli, N.; Occhipinti, S.; Marcucci, L.; De Meo, G.; Innocenti, A.; Ferri, R.; Bruni, O. Using pharmacotherapy to address sleep disturbances in autism spectrum disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2023, 23, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, H.A.; de Castro, C.T.; da Silva, D.C.G.; Pereira, M. Melatonin for sleep disorders in people with autism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 123, 110695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayyat, E.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Sans Capdevila, O.; Maarafeya, M.M.A.; Gozal, D. Obstructive sleep apnea in children: Relative contributions of body mass index and adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Chest 2009, 136, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; de Bruin, E.; Michael, G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-i) in School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Sleep Med. Clin. 2019, 14, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R. Effects of Physical Activity on Children’s Executive Function: Contributions of Experimental Research on Aerobic Exercise. Dev. Rev. 2010, 30, 331–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.; Langendorfer, S.; Roberton, M.A. The Association Between Motor Skill Competence and Physical Fitness in Young Adults. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leisman, G.; Alfasi, R.; D’Angiulli, A. Emotional Brain Development: Neurobiological Indicators from Fetus Through Toddlerhood. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, P.; Korf, H.W.; Kuffer, L.; Groß, J.V.; Erren, T.C. Exercise time cues (zeitgebers) for human circadian systems can foster health and improve performance: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudgel, D.W.; Patel, S.R.; Ahasic, A.M.; Bartlett, S.J.; Bessesen, D.H.; Coaker, M.A.; Fiander, P.M.; Grunstein, R.R.; Gurubhagavatula, I.; Kapur, V.K.; et al. The Role of Weight Management in the Treatment of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e70–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, H. Effects of Exercise on Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffanello, M.; Piacentini, G.; Nosetti, L.; Zoccante, L. Sleep Disordered Breathing in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An In-Depth Review of Correlations and Complexities. Children 2023, 10, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, J.; Nguyen, D.P.; Lechat, B.; Scott, H.; Toson, B.; Manners, J.; Dunbar, C.; Sansom, K.; Pinilla, L.; Hudson, A.; et al. Bidirectional associations between sleep and physical activity investigated using large-scale objective monitoring data. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere-Rubio, N.; Aguas, M.; Faubel, R. Association between Chronotype, Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Hong, K.S.; Park, J.; Park, W. Readjustment of circadian clocks by exercise intervention is a potential therapeutic target for sleep disorders: A narrative review. Phys. Act. Nutr. 2024, 28, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngstedt, S.D.; Kline, C.E.; Elliott, J.A.; Zielinski, M.R.; Devlin, T.M.; Moore, T.A. Circadian Phase-Shifting Effects of Bright Light, Exercise, and Bright Light + Exercise. J. Circadian Rhythm. 2016, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrofsky, R.R.; Reyes, B.A.S.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Bhatnagar, S.; Kirby, L.G.; Van Bockstaele, E.J. Endocannabinoids, stress signaling, and the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psarianos, A.E.; Philippou, A.; Papadopetraki, A.; Chatzinikita, E.; Chryssanthopoulos, C.; Theos, A.; Theocharis, A.; Tzavara, C.; Paparrigopoulos, T. Cortisol and β-Endorphin Responses During a Two-Month Exercise Training Program in Patients with an Opioid Use Disorder and on a Substitution Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizzi, A.L.; Karelis, A.D.; Heisz, J.J. Physical Activity and Mindfulness are Associated with Lower Anxiety in Different but Complementary Ways. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 15, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Miniati, M.; Caruso, V.; Alfi, G.; Geoffroy, P.A.; Domschke, K.; Riemann, D.; Gemignani, A.; Pini, S. Insomnia, anxiety and related disorders: A systematic review on clinical and therapeutic perspective with potential mechanisms underlying their complex link. Neurosci. Appl. 2024, 3, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoff, J.; Wiebe, S.T.; Gruber, R. Sleep patterns and the risk for ADHD: A review. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2012, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, R.R.; Sułkowska, J.Z. Methylphenidate, Sleep, and the “Stimulant Paradox” in Adult ADHD: A Conceptual Framework for Integrating Chronopharmacotherapy and Coaching. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Nikolaou, G.; Boutsinas, B. Digital and AI-Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: Neurocognitive Mechanisms and Clinical Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, S.; Jorgić, B.M.; Olanescu, M.; Popa, I.D. Barriers to Physical Activity Participation in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cao, L.; Zhou, D. The impact of physical activities on adolescents’ rule consciousness: The chain mediation effect of friendship quality and emotional intelligence. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1581016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Total Population | ASD | ASD with Sleep Disorders | Non-ASD | Non-ASD with Sleep Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 155,860,529 | 588,517 | 113,347 | 155,272,012 | 8,650,620 |

| Pediatrics | |||||

| 5–18 y | 20,101,796 | 344,244 | 66,372 | 19,757,552 | 666,416 |

| 5–11 y | 9,481,826 | 180,784 | 33,381 | 9,301,042 | 321,379 |

| 12–18 y | 10,619,970 | 163,460 | 32,991 | 10,456,510 | 345,037 |

| Characteristics | Before Matching | After Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | |||

| Count | 3732 | 35,244 | 3709 | 3709 | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age at onset | ||||||||

| 5–11 years | 2311 (61.9%) | 25,421 (72.1%) | <0.001 | 2306 (62.2%) | 2342 (63.1%) | 0.39 | ||

| 12–18 years | 1154 (30.9%) | 7540 (21.4%) | 1138 (30.7%) | 1114 (30.0%) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1026 (27.5%) | 8551 (24.3%) | <0.001 | 1016 (27.4%) | 988 (26.6%) | 0.46 | ||

| Male | 2681 (71.8%) | 26,215 (74.4%) | 2668 (71.9%) | 2700 (72.8%) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 2372 (63.6%) | 19,851 (56.3%) | <0.001 | 2353 (63.4%) | 2426 (65.4%) | 0.08 | ||

| Black or African American | 589 (15.8%) | 5494 (15.6%) | 588 (15.9%) | 559 (15.1%) | ||||

| Asian | 20 (0.5%) | 175 (0.5%) | 20 (0.5%) | 19 (0.5%) | ||||

| AIAN | 88 (2.4%) | 1020 (2.9%) | 88 (2.4%) | 93 (2.5%) | ||||

| NHPI | 10 (0.3%) | 60 (0.2%) | 10 (0.3%) | 10 (0.3%) | ||||

| Other Race | 312 (8.4%) | 2971 (8.4%) | 310 (8.4%) | 285 (7.7%) | ||||

| Unknown Race | 345 (9.2%) | 5673 (16.1%) | 344 (9.3%) | 324 (8.7%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 2552 (68.4%) | 22,413 (63.6%) | <0.001 | 2535 (68.3%) | 2627 (70.8%) | 0.40 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 650 (17.4%) | 6213 (17.6%) | 644 (17.4%) | 617 (16.6%) | ||||

| Unknown Ethnicity | 530 (14.2%) | 6618 (18.8%) | 530 (14.3%) | 465 (12.5%) | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Asthma | 973 (26.1%) | 5341 (15.2%) | <0.001 | 959 (25.9%) | 937 (25.3%) | 0.56 | ||

| Overweight | 212 (5.7%) | 926 (2.6%) | <0.001 | 205 (5.5%) | 178 (4.8%) | 0.16 | ||

| Obesity | 697 (18.7%) | 3931 (11.2%) | <0.001 | 682 (18.4%) | 637 (17.2%) | 0.17 | ||

| Mood disorders | 837 (22.4%) | 3511 (10%) | <0.001 | 820 (22.1%) | 789 (21.3%) | 0.38 | ||

| Anxiety disorders | 1910 (51.2%) | 8968 (25.4%) | <0.001 | 1887 (50.9%) | 1896 (51.1%) | 0.83 | ||

| Intellectual Disabilities | 400 (10.7%) | 1750 (5%) | <0.001 | 387 (10.4%) | 400 (10.8%) | 0.62 | ||

| ADHD | 2129 (57%) | 13,076 (37.1%) | <0.001 | 2107 (56.8%) | 2129 (57.4%) | 0.61 | ||

| Epilepsy | 388 (10.4%) | 2534 (7.2%) | <0.001 | 382 (10.3%) | 390 (10.5%) | 0.76 | ||

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 1624 (43.5%) | 6421 (18.2%) | <0.001 | 1602 (43.2%) | 1616 (43.6%) | 0.74 | ||

| Sleep-related medications | ||||||||

| Melatonin | 1090 (29.2%) | 4388 (12.5%) | <0.001 | 1072 (28.9%) | 1031 (27.8%) | 0.29 | ||

| Sedatives/hypnotics | 1585 (42.5%) | 7335 (20.8%) | <0.001 | 1564 (42.2%) | 1571 (42.4%) | 0.87 | ||

| Methylphenidate | 937 (25.1%) | 5504 (15.6%) | <0.001 | 925 (24.9%) | 926 (25.0%) | 0.98 | ||

| Amphetamines | 727 (19.5%) | 4152 (11.8%) | <0.001 | 716 (19.3%) | 720 (19.4%) | 0.91 | ||

| Type | Follow-Up Time | Before Matching | After Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | ||

| Insomnia | After 1 y | −60.06 | 16.37 | 0.001 | −59.81 | −10.71 | 0.042 |

| After 5 y | −43.54 | 57.59 | <0.001 | −43.34 | 18.21 | 0.23 | |

| Hypersomnia | After 1 y | −21.71 | 29.04 | 0.06 | −60.16 | −18.81 | 0.22 |

| After 5 y | −30.23 | 86.14 | <0.001 | −32.03 | −5.94 | 0.82 | |

| Circadian rhythm sleep disorders | After 1 y | −72.09 | −20.82 | 0.30 | −71.65 | −19.12 | 0.035 |

| After 5 y | −48.06 | 25.10 | 0.91 | −47.24 | 11.76 | 0.45 | |

| Sleep apnea | After 1 y | −62.30 | −8.90 | 0.006 | −62.26 | 9.39 | 0.004 * |

| After 5 y | −47.79 | 12.61 | 0.88 | −47.69 | 8.82 | 0.027 | |

| Parasomnia | After 1 y | −83.56 | −21.94 | 0.040 | −83.33 | −1.79 | 0.016 |

| After 5 y | −64.38 | 2.16 | 0.48 | −63.89 | −14.29 | 0.048 | |

| Subgroup | Type of Sleep Disorders | 1-Year Follow-Up | 5-Year Follow-Up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | Physical Activity | No Physical Activity | p-Value | ||

| 5–11 years | Sleep disorders | −56.30 | −7.05 | 0.036 | −60.61 | −49.92 | 0.49 |

| Insomnia | −52.00 | −27.43 | 0.025 | −41.65 | −6.64 | 0.06 | |

| Hypersomnia | −28.57 | 19.47 | 0.79 | −9.52 | 2.63 | 0.96 | |

| Circadian rhythm sleep disorders | −50.00 | −13.64 | 0.041 | −59.62 | −16.36 | 0.007 | |

| Sleep apnea | −64.22 | −10.00 | 0.78 | −63.20 | −52.67 | 0.45 | |

| Parasomnia | −73.33 | −16.15 | 0.036 | −73.33 | −12.31 | 0.56 | |

| 12–18 years | Sleep disorders | −82.91 | −21.00 | 0.003 * | −80.06 | −7.14 | <0.001 * |

| Insomnia | −68.77 | −22.43 | 0.032 | −60.89 | −36.45 | 0.006 | |

| Hypersomnia | −10.00 | 18.00 | 0.13 | −14.62 | 24.00 | 0.31 | |

| Circadian rhythm sleep disorders | −44.44 | −37.84 | 0.64 | −22.22 | −24.32 | 1.00 | |

| Sleep apnea | −80.42 | −14.46 | 0.036 | −81.47 | 20.46 | <0.001 * | |

| Parasomnia | −50.00 | −53.33 | 1.00 | −53.85 | −56.67 | 1.00 | |

| Type | ADHD (n = 4896) | Anxiety (n = 4010) | Epilepsy (n = 880) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disorders | |||

| 1 y | −54.2 vs. −8.3 ** | −58.7 vs. −12.4 ** | −45.6 vs. −2.8 * |

| 5 y | −46.8 vs. +5.4 ** | −51.2 vs. +3.9 ** | −38.9 vs. +8.7 * |

| Insomnia | |||

| 1 y | −55.4 vs. −15.2 * | −61.8 vs. −18.6 ** | −48.2 vs. −8.9 * |

| 5 y | −41.2 vs. +12.4 * | −45.6 vs. +15.8 ** | −35.4 vs. +20.3 |

| Hypersomnia | |||

| 1 y | −58.4 vs. −20.3 | −62.5 vs. −22.4 | −45.2 vs. −15.6 |

| 5 y | −30.6 vs. −8.2 | −35.8 vs. −10.4 | −28.4 vs. −4.8 |

| Circadian rhythm sleep disorders | |||

| 1 y | −68.4 vs. −22.3 * | −73.8 vs. −25.6 ** | −55.4 vs. −12.8 * |

| 5 y | −45.6 vs. +8.9 | −50.2 vs. +10.4 * | −40.2 vs. +15.6 |

| Sleep apnea | |||

| 1 y | −60.4 vs. +5.8 ** | −65.8 vs. +8.9 ** | −52.4 vs. +12.6 * |

| 5 y | −45.8 vs. +6.4 * | −50.2 vs. +10.2 ** | −42.8 vs. +15.4 * |

| Parasomnia | |||

| 1 y | −80.4 vs. −5.2 ** | −85.6 vs. −8.4 ** | −75.4 vs. +2.8 ** |

| 5 y | −60.2 vs. −18.4 * | −65.8 vs. −20.6 * | −55.4 vs. −10.6 * |

| Medication/Group | Baseline | Follow-Up | Absolute Change | Change vs. Control | p-Value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 28.90% | 17.10% | −11.80% | 2.60% | 0.001 * | 1.21 | (1.078, 1.357) |

| No Physical Activity | 27.80% | 14.50% | −13.30% | Reference | |||

| Methylphenidate | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 24.90% | 19.20% | −5.70% | −1.30% | 0.17 | 0.928 | (0.838, 1.028) |

| No Physical Activity | 25.00% | 20.50% | −4.50% | Reference | |||

| Amphetamines | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 19.30% | 15.00% | −4.30% | −1.90% | 0.024 | 0.865 | (0.771, 0.969) |

| No Physical Activity | 19.40% | 16.90% | −2.50% | Reference |

| Medication/Group | Baseline | Follow-Up | Absolute Change | Change vs. Control | p-Value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD (N = 4896) | |||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 33.00% | 19.40% | −13.60% | 3.70% | 0.001 * | 1.303 | (1.139, 1.491) |

| No Physical Activity | 32.60% | 15.70% | −16.90% | Reference | |||

| Methylphenidate | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 37.30% | 27.40% | −9.90% | −0.10% | 0.85 | 1.003 | (0.902, 1.116) |

| No Physical Activity | 37.90% | 27.60% | −10.30% | Reference | |||

| Amphetamines | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 28.90% | 21.70% | −7.20% | −1.30% | 0.21 | 0.937 | (0.832, 1.054) |

| No Physical Activity | 29.20% | 23.20% | −6.00% | Reference | |||

| Anxiety (N = 4010) | |||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 32.90% | 19.20% | −13.70% | 4.00% | 0.001 * | 1.334 | (1.147, 1.550) |

| No Physical Activity | 31.00% | 15.20% | −15.80% | Reference | |||

| Methylphenidate | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 32.60% | 23.00% | −9.60% | 0.10% | 0.94 | 1.032 | (0.907, 1.174) |

| No Physical Activity | 34.00% | 22.90% | −11.10% | Reference | |||

| Amphetamines | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 25.60% | 18.30% | −7.30% | −0.90% | 0.44 | 0.955 | (0.827, 1.102) |

| No Physical Activity | 26.00% | 19.20% | −6.80% | Reference | |||

| Epilepsy (N = 880) | |||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 33.60% | 23.60% | −10.00% | 3.40% | 0.22 | 1.135 | (0.855, 1.507) |

| No Physical Activity | 34.50% | 20.20% | −14.30% | Reference | |||

| Methylphenidate | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 22.00% | 17.30% | −4.70% | 2.10% | 0.41 | 1.118 | (0.805, 1.553) |

| No Physical Activity | 21.10% | 15.20% | −5.90% | Reference | |||

| Amphetamines | |||||||

| Physical Activity | 13.40% | 9.10% | −4.30% | −4.10% | 0.054 | 0.633 | (0.423, 0.948) |

| No Physical Activity | 13.00% | 13.20% | 0.20% | Reference |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toraih, E.A.; Zeleny, J.; Sames, C.; Craig, A.; Hagearty-Mattern, C.; Coyle, S.; Lois, A.; Elshazli, R.M.; Aiash, H. Breaking the Cycle: Impact of Physical Activity on Sleep Disorders in Autism—A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis. Children 2026, 13, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010048

Toraih EA, Zeleny J, Sames C, Craig A, Hagearty-Mattern C, Coyle S, Lois A, Elshazli RM, Aiash H. Breaking the Cycle: Impact of Physical Activity on Sleep Disorders in Autism—A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis. Children. 2026; 13(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleToraih, Eman A., Jason Zeleny, Carol Sames, Andrew Craig, Catherine Hagearty-Mattern, Sierra Coyle, Amanda Lois, Rami M. Elshazli, and Hani Aiash. 2026. "Breaking the Cycle: Impact of Physical Activity on Sleep Disorders in Autism—A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis" Children 13, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010048

APA StyleToraih, E. A., Zeleny, J., Sames, C., Craig, A., Hagearty-Mattern, C., Coyle, S., Lois, A., Elshazli, R. M., & Aiash, H. (2026). Breaking the Cycle: Impact of Physical Activity on Sleep Disorders in Autism—A Five-Year Longitudinal Analysis. Children, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010048