Children’s Socioemotional Strengths in Early Childhood Education (ECE) and Before/After School Care (BASC): A Multilevel Ecological Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Socioemotional Strengths

1.2. Contextual Influences on Socioemotional Strengths

1.2.1. Socioeconomic Status (SES)

1.2.2. Early Childhood Education and Before/After School Care

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variable: Strengths

2.2.2. Predictor Variable: Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Status

2.2.3. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Missing Data

3. Results

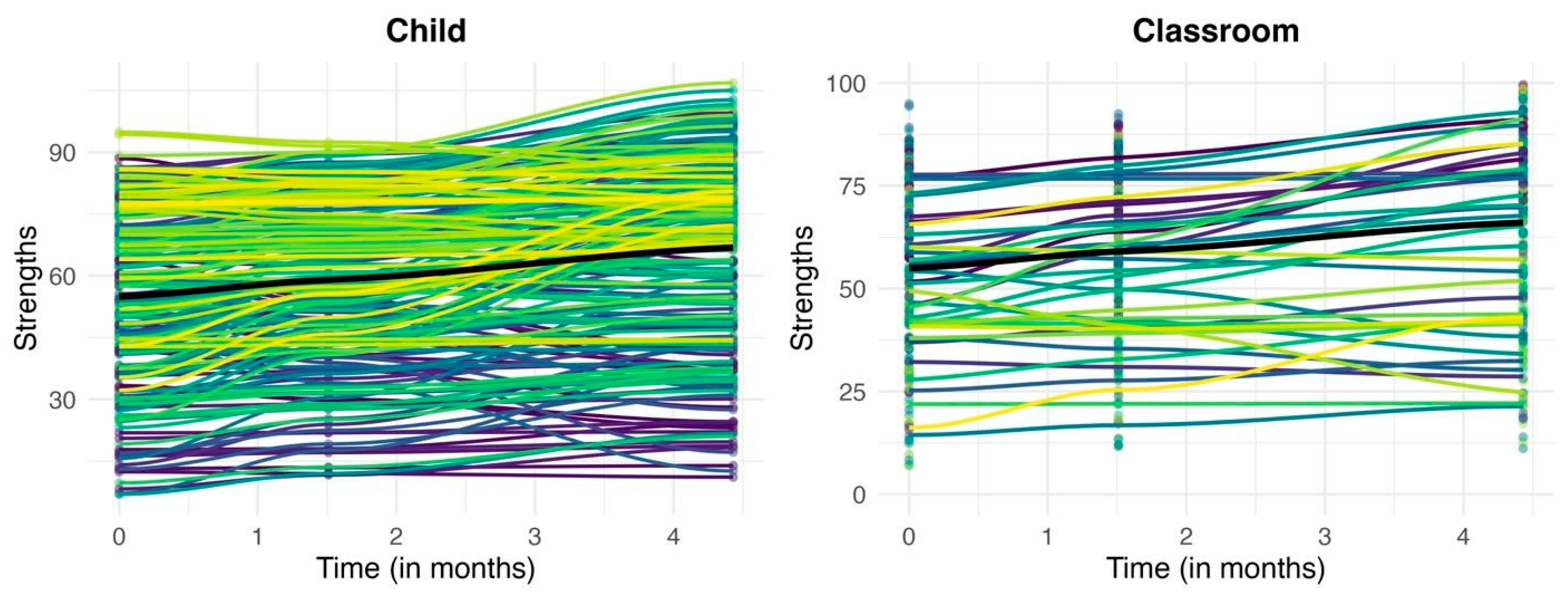

3.1. Question 1: Variance Partitioning

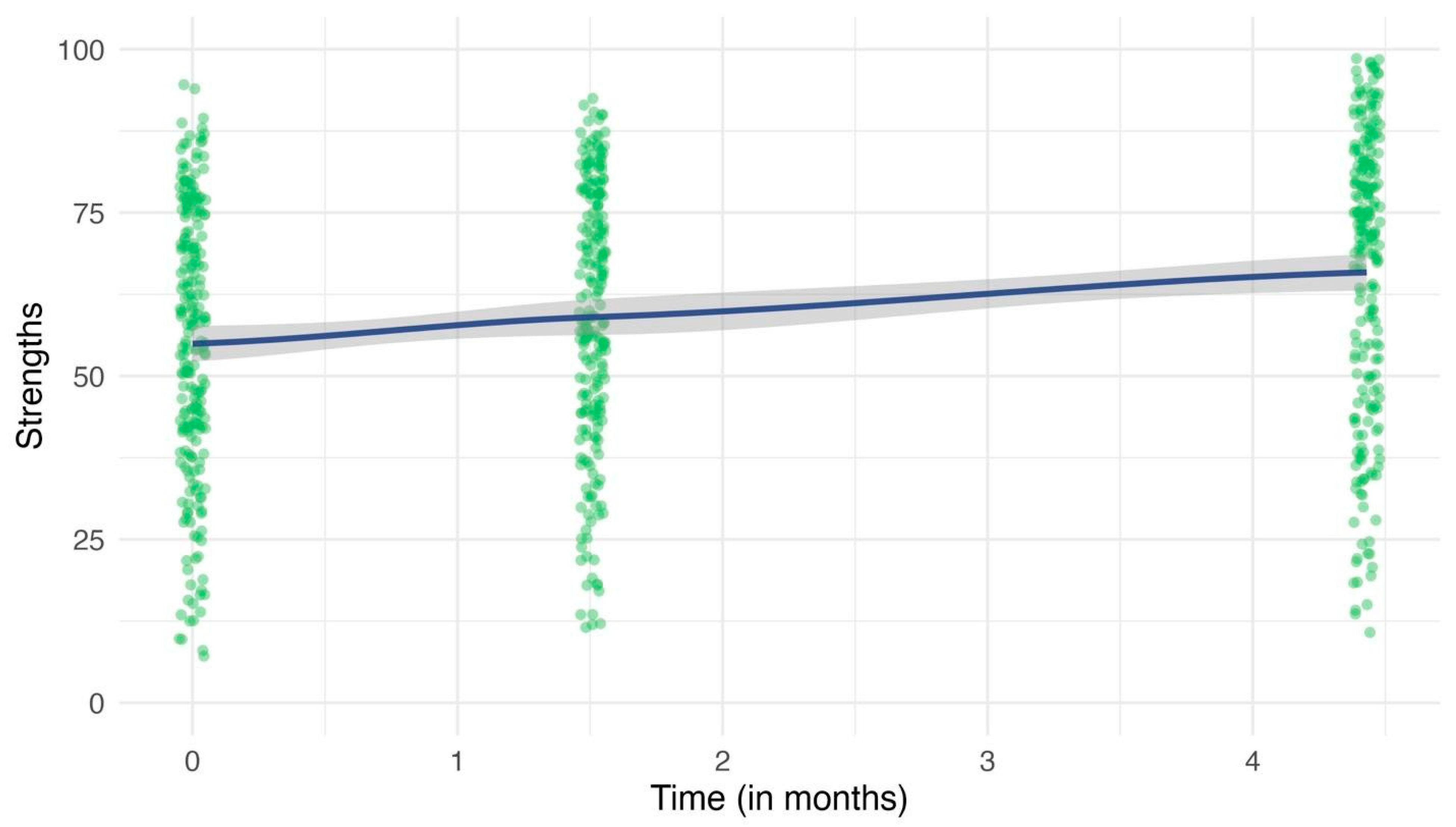

3.2. Question 2: Growth Model

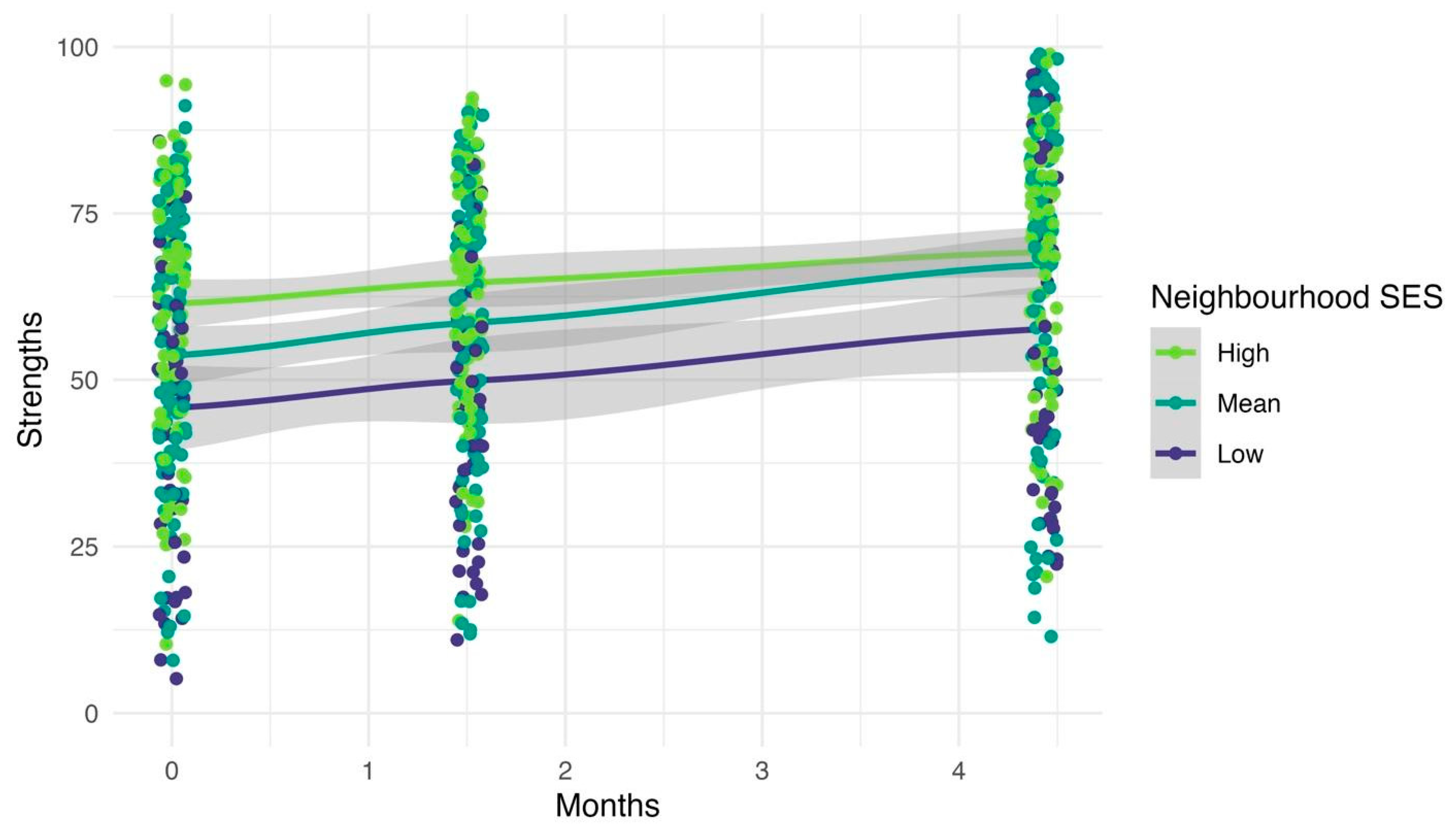

3.3. Question 3: Predictor Variables

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Predictors of Levels and Trajectories of Socioemotional Strengths

4.2. Socioemotional Strengths as an Individual-Level Phenomenon

4.3. Socioemotional Strengths as a Classroom-Level Phenomenon

4.4. Socioemotional Strengths as a School-Level Phenomenon

4.5. Implications

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomez, R. Sustaining the benefits of early childhood education experiences: A research overview. Voices Urban Educ. 2016, 43, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Minney, D.; Garcia, J.; Altobelli, J.; Perez-Brena, N. Social-emotional learning and evaluation in after-school care: A working model. J. Youth Dev. 2019, 14, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondi, C.F.; Giovanelli, A.; Reynolds, A.J. Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood intervention. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2021, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoyd, V.C. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, C.E. The longitudinal effects of after-school program experiences, quantity, and regulatable features on children’s social–emotional development. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 48, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman Equation. ABC/CARE: Elements of Quality Early Childhood Programs that Produce Quality Outcomes. 2025. Available online: https://heckmanequation.org/resource/abc-care-elements-of-quality-early-childhood-programs-that-produce-quality-outcomes/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Roberts-Holmes, G.; Bradbury, A. The datafication of early years education and its impact upon pedagogy. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Vitiello, G. Preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom process quality, and children’s social skills: A multilevel mediation analysis. Early Child. Res. Q. 2021, 55, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviruusu, O.; Björklund, K.; Koskinen, H.L.; Liski, A.; Lindblom, J.; Kuoppamäki, H.; Alasuvanto, P.; Ojala, T.; Sam-posalo, H.; Harmes, N.; et al. Short-term effects of the “Together at School” intervention program on children’s socio-emotional skills: A cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Westhues, A.; MacLeod, J. A meta-analysis of longitudinal research on preschool prevention pro-grams for children. Prev. Treat. 2003, 6, 31a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.J.; Temple, J.A.; Ou, S.; Robertson, D.L.; Mersky, J.P.; Topitzes, J.W.; Niles, M.D. Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being: A 19-year follow-up of low-income families. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasbash, J.; Leckie, G.; Pillinger, R.; Jenkins, J. Children’s educational progress: Partitioning family, school and area effects. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 2010, 173, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sloss, I.M.; Maguire, N.; Browne, D.T. Physical activity and social-emotional learning in Canadian children: Multilevel perspectives within an early childhood education and care setting. Soc. Emot. Learn. Res. Pract. Policy 2024, 4, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, D.T.; McArthur, B.A.; Racine, N. Editorial: Multilevel social determinants of individual and family well-being: National and international perspectives. Front. Epidemiol. 2024, 4, 1381516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, D.; Lechner, C.M.; Spengler, M. Editorial: Do we need socio-emotional skills? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 723470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.E.; Greenberg, M.; Crowley, M. Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.E.; Johnson, L.R.; Minnes, S.; Miller, E.K.; Riccardi, J.S.; Dimitropoulos, A. Predictors of social emotional learning in after-school programming: The impact of relationships, belonging, and program engagement. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 1318–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASEL. What Is the CASEL Framework? Available online: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kim, E.K.; Allen, J.P.; Jimerson, S.R. Supporting student social emotional learning and development. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 53, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Hunt, J.; Speer, N. Mental health in American colleges and universities: Variation across student subgroups and across campuses. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.; Marwaha, R. Developmental Stages of Social Emotional Development in Children; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, T.G.; Darling-Churchill, K.E. Review of measures of social and emotional development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 45, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBuffe, P.A.; Naglieri, J.A. Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Preschoolers, 2nd ed.; Kaplan Early Learning Company: Lewisville, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- LeBuffe, P.A.; Shapiro, V.B.; Naglieri, J.A. Devereux Student Strengths Assessment: K-8th Grade: A Measure of Social-Emotional Competencies of Children in Kindergartern Through Eight Grade; Aperture Education: Fort Mill, SC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://measuringsel.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DESSA-User-Manual.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Mackrain, M.; LeBuffe, P.; Powell, G. Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Infants and Toddlers; Kaplan Early Learning Company: Lewisville, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, D.T.; Wade, M.; Prime, H.; Jenkins, J.M. School readiness amongst urban Canadian families: Risk profiles and family mediation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, F.; Darling-Hammond, L. Funding disparities and the inequitable distribution of teachers: Evaluating sources and solutions. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2012, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, D.C.; Connors, M.C.; Morris, P.A.; Yoshikawa, H.; Friedman-Krauss, A.H. Neighborhood economic disadvantage and children’s cognitive and social-emotional development: Exploring Head Start classroom quality as a mediating mechanism. Early Child. Res. Q. 2015, 32, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarik, A.S.; Conger, R.D. Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murano, D.; Sawyer, J.E.; Lipnevich, A.A. A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 90, 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, C.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Nolan, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Vicary, D.; Huang, T.; McCabe, P.; McKay, T.; Skouteris, H. Social and emotional learning associated with universal curriculum-based interventions in early childhood education and care centers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e185727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Pachan, M. A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 45, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Reichow, B.; Snyder, P.; Harrington, J.; Polignano, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of classroom-wide social–emotional interventions for preschool children. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2022, 42, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiabi, G.S. Play in the preschool classroom: Its socioemotional significance and the teacher’s role in play. Early Child. Educ. J. 2007, 35, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Bouffard, S.M. Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies. Soc. Policy Rep. 2012, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbright, T.N.; Marsh, J.A.; Kennedy, K.E. Social-emotional learning practices: Insights from outlier schools. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2019, 12, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A. Social and emotional learning and teachers. Future Child. 2017, 27, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, T.; Degotardi, S. Design-based research in early childhood education: A scoping review of methodologies. Early Child. Educ. J. 2024, 53, 2795–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Stabile, M.; Koebel, K.; Furzer, J. The effect of household earnings on child school mental health designations: Evidence from administrative data. J. Hum. Resour. 2024, 59, S41–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population. 2023. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; DebRoy, S.; Sarkar, D.; Heisterkamp, S.; Van Willigen, B.; Ranke, J. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Stekhoven, D.J.; Bühlmann, P. MissForest: Nonparametric missing value imputation using random forest. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.N.; Rosdi, M.N.A.; Jamaludin, K.R.; Ramlie, F.; Talib, H.A. Imputation analysis of time-series data using a random forest algorithm. In Intelligent Manufacturing and Mechatronics: iM3F 2023; Isa, M., Khairuddin, W.H., Razman, I.M.M., Saruchi, M.A., Teh, S., Liu, S.H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenowatz, C.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Welk, G.; Heelan, K.; Gentile, D.; Walsh, D. Influence of so-cio-economic status on habitual physical activity and sedentary behavior in 8- to 11-year old children. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijtzes, A.I.; Jansen, W.; Bouthoorn, S.H.; Pot, N.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Raat, H. Social inequalities in young children’s sports participation and outdoor play. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, W.; Chung, K.K.; Cheng, R.W. Gender differences in social mastery motivation and its rela-tionships to vocabulary knowledge, behavioral self-regulation, and socioemotional skills. Early Educ. Dev. 2019, 30, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienclaw, R. Gender Roles. In Sociology Reference Guide: Gender Roles & Equality; The Editors of Salem Press, Eds.; Salem Press: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men. 2018. Available online: http://www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-boys-men-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Parker, S.; Perlman, M.; Prime, H.; Jenkins, J. Caregiver cognitive sensitivity: Measure development and vali-dation in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) settings. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 45, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Klinger, D.A. Hierarchical linear modeling of student and school effects on academic achievement. Can. J. Educ. 2000, 25, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoach, D.B.; Gubbins, E.J.; Foreman, J.; Rubenstein, L.D.; Rambo-Hernandez, K.E. Evaluating the Efficacy of Using Predifferentiated and Enriched Mathematics Curricula for Grade 3 Students: A Multisite Cluster-Randomized Trial: A Multisite Cluster-Randomized Trial. Gift. Child Q. 2014, 58, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | −0.21 * | 0.11 * | 0.08 * | −0.01 | 4.60 | 2.21 |

| 2. SES disadvantage | – | −0.25 * | −0.14 * | −0.17 * | 15.32 | 4.42 |

| 3. Total Strengths T1 | – | 0.56 * | 0.53 * | 52.65 | 27.61 | |

| 4. Total Strengths T2 | – | 0.64 * | 62.49 | 26.43 | ||

| 5. Total Strengths T3 | – | 65.66 | 27.07 |

| Boys (0) | Girls (1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Time 1 | ||||

| Infants | –* | –* | 66.46 | 19.53 |

| Toddlers | 46 | 33.74 | 47.75 | 30.45 |

| Preschoolers | 42.81 | 31.84 | 52.87 | 28.56 |

| School | 50.38 | 26.83 | 60.97 | 23.11 |

| Time 2 | ||||

| Infants | –* | –* | 76.92 | 12.49 |

| Toddlers | 55.32 | 36.65 | 66.15 | 33.63 |

| Preschoolers | 54.38 | 28.91 | 63.45 | 26.32 |

| School | 58.11 | 26.86 | 67.8 | 20.68 |

| Time 3 | ||||

| Infants | –* | –* | –* | –* |

| Toddlers | 64.68 | 34.11 | 80.95 | 19.59 |

| Preschoolers | 61.96 | 35.86 | 65 | 23.79 |

| School | 56.81 | 28.91 | 70.47 | 18.97 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | b [95% CI] | b [95% CI] | b [95% CI] | b [95% CI] |

| Intercept | 54.86 * [44.17, 65.55] | 49.54 * [38.75, 60.33] | 50.58 * [41.41, 59.76] | 67.04 * [50.46, 83.62] |

| Months | 2.69 * [1.95, 3.42] | 2.16 * [0.43, 3.90] | 2.45 * [1.04, 3.85] | |

| Age | 4.04 * [1.56, 6.52] | |||

| Toddler | −5.15 [−16.37, 6.07] | |||

| Preschool | −24.73 * [−40.28, −9.18] | |||

| School | −24.00 * [−42.45, −5.55] | |||

| Girl | 9.77 * [5.09, 14.46] | |||

| Gender minority | 5.52 [−5.83, 16.86] | |||

| SES disadvantage | −1.38 * [−2.56, −0.19] | |||

| Months * SES disadvantage | 0.02 [−0.23, 0.27] | |||

| Random Effects | SD [95% CI] | SD [95% CI] | SD [95% CI] | SD [95% CI] |

| Level 4 | ||||

| Random intercept | 12.77 * [6.00, 27.18] | 12.77 * [6.00, 27.18] | 10.37 * [4.39, 24.51] | 10.32 * [4.36, 24.41] |

| Random slope | 1.44 * [0.37, 5.65] | |||

| Cov (Intercept/Months) | 0.79 [−0.95, 1.00] | |||

| Level 3 | ||||

| Random intercept | 11.97 * [8.41, 17.04] | 11.97 * [8.41, 17.03] | 11.03 * [7.21, 16.89] | 10.40 * [6.64, 16.28] |

| Random slope | 3.54 * [2.57, 4.88] | 3.68 * [2.71, 4.99] | ||

| Cov (Intercept/Months) | −0.20 [−0.60, 0.28] | −0.23 [−0.65, 0.30] | ||

| Level 2 | ||||

| Random intercept | 13.95 * [11.81, 16.47] | 14.37 * [12.30, 16.79] | 17.98 * [15.50, 20.86] | 17.13 * [14.69, 19.98] |

| Random slope | 1.39 * [0.83, 2.33] | 1.57 * [0.98, 2.52] | ||

| Cov (Intercept/Months) | −0.98 [−1.00, 0.31] | −0.98 * [−1.00, −0.25] | ||

| Level 1 | ||||

| Random intercept | 18.80 * [17.62, 20.07] | 17.82 * [16.70, 19.03] | 15.36 * [14.35, 16.44] | 15.30 * [14.29, 16.38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sloss, I.M.; Maguire, N.; Browne, D.T. Children’s Socioemotional Strengths in Early Childhood Education (ECE) and Before/After School Care (BASC): A Multilevel Ecological Analysis. Children 2026, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010023

Sloss IM, Maguire N, Browne DT. Children’s Socioemotional Strengths in Early Childhood Education (ECE) and Before/After School Care (BASC): A Multilevel Ecological Analysis. Children. 2026; 13(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSloss, Imogen M., Nicola Maguire, and Dillon T. Browne. 2026. "Children’s Socioemotional Strengths in Early Childhood Education (ECE) and Before/After School Care (BASC): A Multilevel Ecological Analysis" Children 13, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010023

APA StyleSloss, I. M., Maguire, N., & Browne, D. T. (2026). Children’s Socioemotional Strengths in Early Childhood Education (ECE) and Before/After School Care (BASC): A Multilevel Ecological Analysis. Children, 13(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010023