Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Neonates with Transient Tachypnea: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Inter-Operator Reliability

Highlights

- •

- Diaphragmatic excursion increases during the first 48 h in healthy neonates.

- •

- On day two, TTN infants show lower diaphragmatic excursion compared with controls, and a negative correlation develops between excursion and LUS, indicating impaired diaphragmatic function in the context of lung disease.

- •

- Diaphragmatic ultrasound may help identify early functional impairment in neonates with TTN, complementing lung ultrasound to characterize disease severity.

- •

- Integrated lung–diaphragm ultrasound assessment may support monitoring of disease progression and guide decisions on respiratory support, especially during the first 48 h of life.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

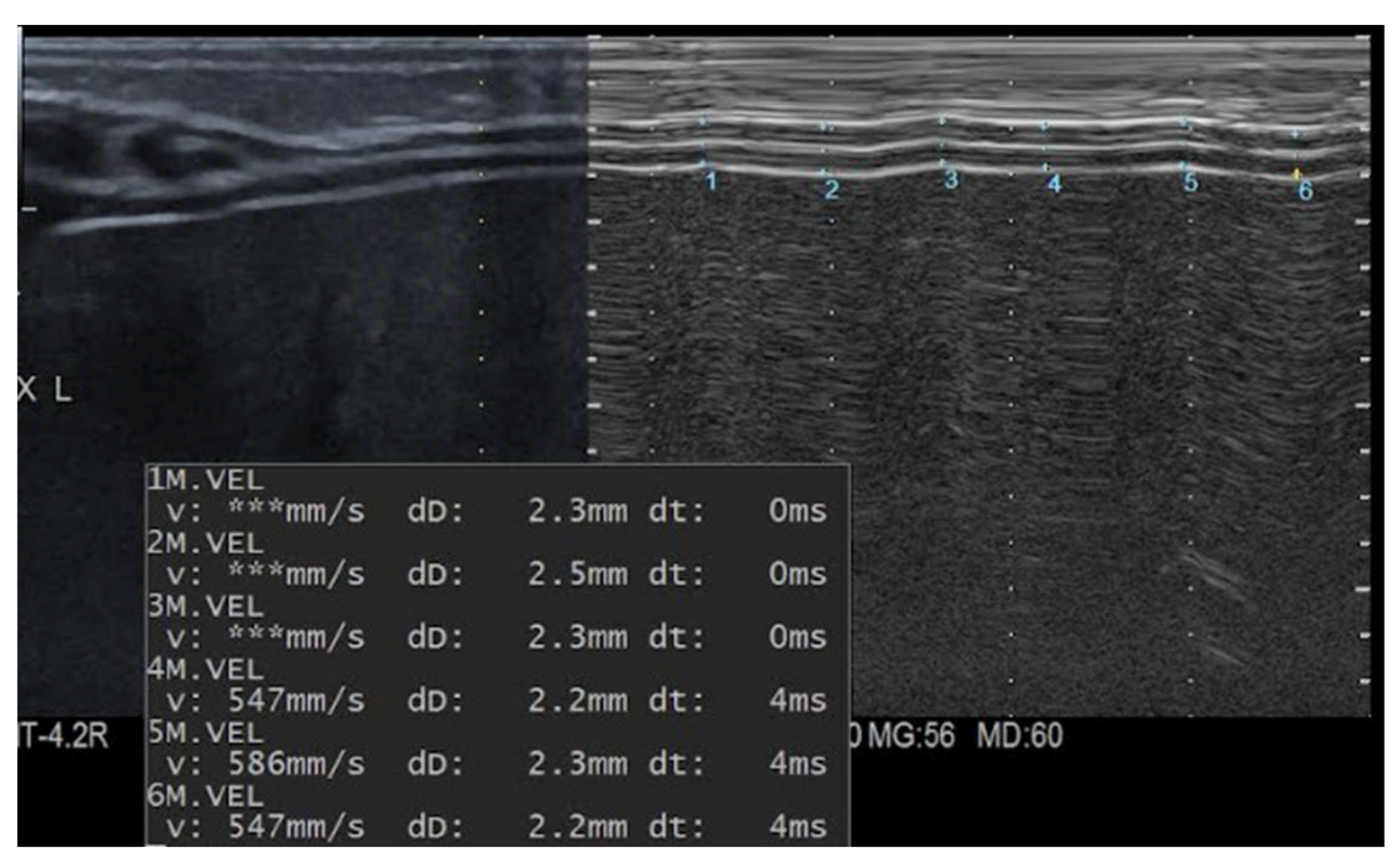

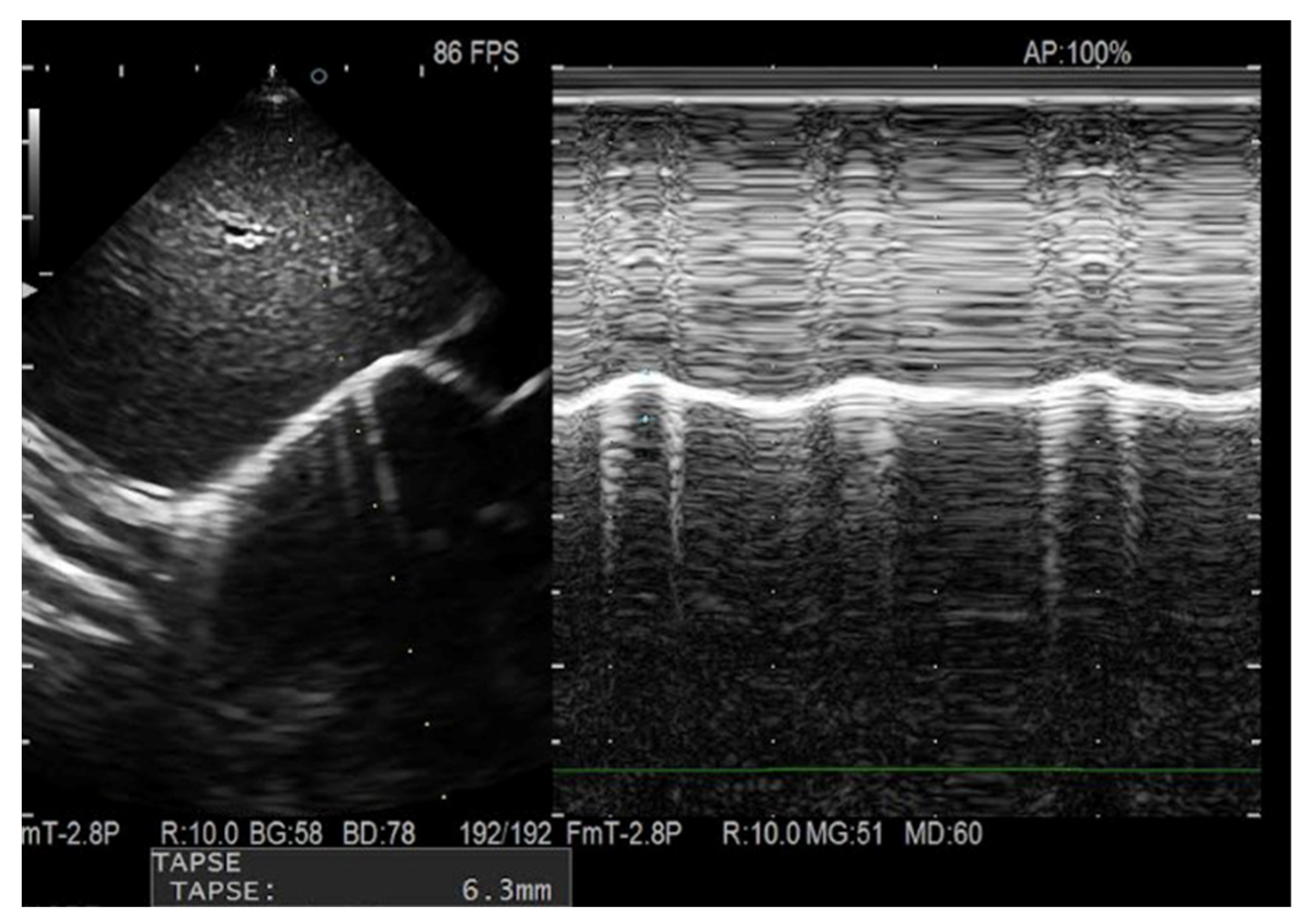

2.1. Ultrasound Equipment and Technique

2.2. Assessment of Reproducibility

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TTN | transient tachypnea of the newborn |

| NIV | non-invasive ventilation |

| GA | gestational age |

| BW | birth weight |

| DTi | End-inspiratory diaphragmatic thickness |

| DTe | End-expiratory diaphragmatic thickness |

| DE | Diaphragmatic excursion |

| DTf | Diaphragm thickening fraction |

| nCPAP | nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure |

| HHHFNC | Heated Humidified High-Flow Nasal Cannula |

| RDS | respiratory distress syndrome |

| LUS | Lung Ultrasound Score |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| CV | coefficient of variation |

| ICC | intraclass correlation coefficient |

| BPD | bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

References

- Alonso-Ojembarrena, A.; Estepa-Pedregosa, L. Can Diaphragmatic Ultrasound Become a New Application for Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Preterm Infants? Chest 2023, 163, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.D.; Lim, J.K.B.; Glau, C. A narrative review of diaphragmatic ultrasound in pediatric critical care. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2471–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halaby, H.; Abdel-Hady, H. Sonographic Evaluation of Diaphragmatic Excursion and Thickness in Healthy Infants and Children. J. Ultrasound Med. 2016, 35, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, Y.; Arai, J. Ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction in extremely preterm infants: A pilot ultrasound study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 1555–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobile, S.; Sbordone, A. Diaphragm atrophy during invasive mechanical ventilation is related to extubation failure in preterm infants: An ultrasound study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhassen, Z.; Vali, P. Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and Management of Transient Tachypnea of Newborn. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, C.; Sartorius, V. Transient tachypnoea: New concepts on the commonest neonatal respiratory disorder. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 240112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, R.; Cattarossi, L. The ‘double lung point’: An ultrasound sign diagnostic of transient tachypnea of the newborn. Neonatology 2007, 91, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brat, R.; Yousef, N. Lung Ultrasonography Score to Evaluate Oxygenation and Surfactant Need in Neonates Treated with Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, e151797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics; Olkin, I., Ed.; Robust tests for equality of variances. Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, B.L. The generalization of “Student’s” problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. On the comparison of several mean values: An alternative approach. Biometrika 1951, 38, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 327, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, B.A.; El-Rahman, A.M.A. Lung and diaphragm ultrasound as predictors of successful weaning from nasal continuous positive airway pressure in preterm infants. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mogy, M.; El-Halaby, H. Comparative Study of the Effects of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Nasal High-Flow Therapy on Diaphragmatic Dimensions in Preterm Infants. Am. J. Perinatol. 2018, 35, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Bandyopadhyay, T. Sonographic assessment of diaphragmatic thickness and excursion to predict CPAP failure in neonates below 34 weeks of gestation: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, V.K.; Laiprasert, J. Diaphragm dimensions of the healthy preterm infant. Pediatrics 2001, 108, E91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Ojembarrena, A.; Morales-Navarro, A. The increase in diaphragm thickness in preterm infants is related to birth weight: A pilot study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 3723–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, S.R.; Sakr, H.M. Diaphragmatic thickness and excursion by lung ultrasound in pediatric chronic pulmonary diseases. J. Ultrasound 2022, 25, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussuges, A.; Gole, Y. Diaphragmatic motion studied by m-mode ultrasonography: Methods, reproducibility, and normal values. Chest 2009, 135, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ojembarrena, A.; Ruiz-González, E. Reproducibility and reference values of diaphragmatic shortening fraction for term and premature infants. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, T.; Mohsen, N. Diaphragmatic Thickness and Excursion in Preterm Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Compared with Term or Near-Term Infants: A Prospective Observational Study. Chest 2023, 163, 324–331.69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos Yamaguti, W.P.; Paulin, E. Air trapping: The major factor limiting diaphragm mobility in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Respirology 2008, 13, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baria, M.R.; Shahgholi, L. B-mode ultrasound assessment of diaphragm structure and function in patients with COPD. Chest 2014, 146, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cases (n.20) | Controls (n.20) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks), mean (±SD) | 37.2 (±2.2) | 38.7 (±1.9) | 0.014 |

| Birth weight (g), mean (±SD) | 2696.4 (±641.2) | 2938.5 (±608.2) | 0.22 |

| Birth length (cm), mean (±SD) | 46.9 (±5.8) | 48.2 (±3.1) | 0.39 |

| Birth cranial circumference (cm), mean (±SD) | 33.4 (±2.3) | 33.4 (±2.3) | 0.71 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 1 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.34 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 (55) | 6 (30) | 0.20 |

| Single born, n (%) | 15 (75) | 17 (85) | 0.69 |

| Mode of delivery (cesarean section), n (%) | 13 (65) | 10 (50) | 0.52 |

| Antenatal steroid therapy, n (%) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 0.27 |

| Apgar score 1 min, median (IQR) | 8 (7–9) | 9 (9–9) | 0.009 |

| Apgar score 5 min, median (IQR) | 9 (8–9) | 10 (10–10) | <0.001 |

| T0 | T1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTN (n. 20) | Controls (n. 20) | p Value | TTN (n. 20) | Controls (n. 20) | p Value | |

| DTi (mm), mean (±SD) | 2.4 (±0.5) | 2.6 (±0.4) | 0.32 | 2.5 (±0.7) | 2.6 (±0.6) | 0.60 |

| DTe (mm), mean (±SD) | 2.1 (±0.5) | 2.3 (±0.3) | 0.19 | 2.2 (±0.6) | 2.4 (±0.6) | 0.36 |

| DTf (%), mean (±SD) | 12.9 (±6.4) | 11.9 (±6.4) | 0.61 | 14.9 (±7.5) | 12.1 (±7.3) | 0.23 |

| DE (mm), mean (±SD) | 4.3(±0.9) | 4.63 (±1.1) | 0.35 | 4.6(±0.9) | 5.4 (±1.3) | 0.03 |

| TTN (n. 20) | Controls (n. 20) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | p Value | T0 | T1 | p Value | |

| DTi (mm), mean (±SD) | 2.4 (±0.5) | 2.5 (± 0.7) | 0.50 | 2.6 (±0.4) | 2.6 (±0.6) | 0.44 |

| DTe (mm), mean (±SD) | 2.1 (±0.5) | 2.2 (±0.6) | 0.59 | 2.3 (±0.3) | 2.4 (±0.6) | 0.47 |

| DTf (%), mean (±SD) | 12.9 (±6.41) | 14.9 (±7.5) | 0.39 | 11.9 (±6.4) | 12.1 (±7.3) | 0.94 |

| DE (mm), mean (±SD) | 4.3 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.9) | 0.36 | 4.6 (±1.1) | 5.4 (±1.3) | 0.04 |

| Diaphragmatic Parameters | Correlation Coefficient r | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | DTi | 0.49 | 0.01 |

| DTe | 0.52 | 0.01 | |

| DE | 0.24 | 0.13 | |

| DTf | −0.19 | 0.23 | |

| Birth weight | DTi | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| DTe | 0.45 | 0.04 | |

| DE | 0.27 | 0.09 | |

| DTf | −0.07 | 0.68 |

| Diaphragmatic Parameters | Operator 1 | Operator 2 | Difference | Limits of Agreement | ICC | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTi | 2.6± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | −1.2–0.8 | 0.52 | 21.1% |

| DTe | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | −1.0–0.7 | 0.66 | 22.8% |

| DE | 4.9 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 0.3± 1.5 | −2.7–2.2 | 0.32 | 21.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Patti, M.L.; Crapanzano, C.; Cerbo, R.M.; Schena, F.; La Rocca, A.; Cortesi, V.; Amelio, G.S.; Ghirardello, S. Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Neonates with Transient Tachypnea: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Inter-Operator Reliability. Children 2026, 13, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010024

Patti ML, Crapanzano C, Cerbo RM, Schena F, La Rocca A, Cortesi V, Amelio GS, Ghirardello S. Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Neonates with Transient Tachypnea: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Inter-Operator Reliability. Children. 2026; 13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010024

Chicago/Turabian StylePatti, Maria Letizia, Carmela Crapanzano, Rosa Maria Cerbo, Federico Schena, Anna La Rocca, Valeria Cortesi, Giacomo Simeone Amelio, and Stefano Ghirardello. 2026. "Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Neonates with Transient Tachypnea: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Inter-Operator Reliability" Children 13, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010024

APA StylePatti, M. L., Crapanzano, C., Cerbo, R. M., Schena, F., La Rocca, A., Cortesi, V., Amelio, G. S., & Ghirardello, S. (2026). Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Neonates with Transient Tachypnea: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Inter-Operator Reliability. Children, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010024