Association Between Sedentary Behavior and Body Image Distortion Among Korean Adolescents Considering Sedentary Purpose

Highlights

- Prolonged sedentary behavior was associated with higher odds of body image distortion in adolescents, with this pattern driven mainly by girls.

- Educational sedentary time (study- and school-related sitting) showed a stronger link to body image distortion than non-educational sedentary time.

- Reducing prolonged sitting for educational purposes and integrating active study routines may help prevent body image distortion, especially among female students.

- School- and community-based programs should address both sedentary time and body image in adolescent health promotion, with particular attention to academic pressure in girls.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

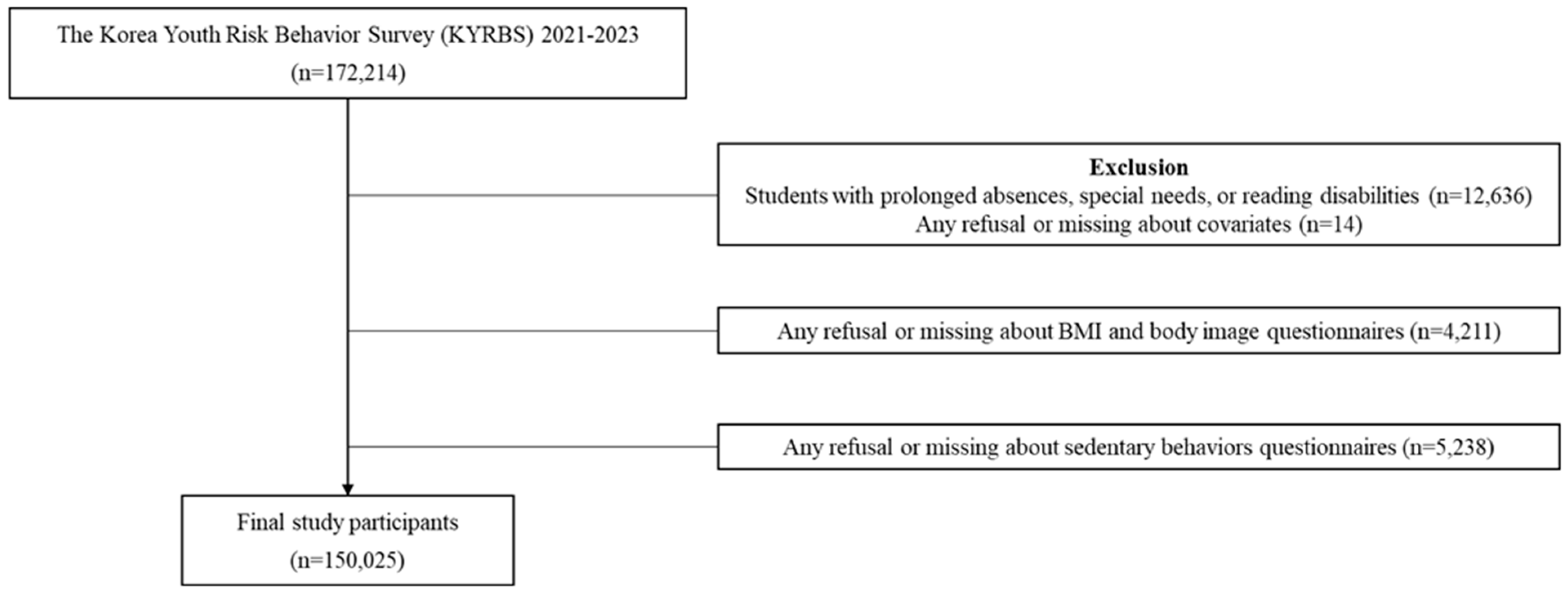

2.1. Data Collection and Study Participants

2.2. Sedentary Time

2.3. Body Image Distortion

2.4. Covariates

- Sociodemographic factors: Sex, school level (middle/high school), academic achievement (high/middle/low), household economic status (high/middle/low), and living arrangement (with family/not).

- Health-related behaviors: Regular breakfast consumption, frequent fast food consumption (≥3 times/week), alcohol consumption, and smoking status, which are known to cluster with sedentary lifestyles.

- Psychological and Physical status: Perceived stress (high/low) and BMI category.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, H.; Jing, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Wan, Y. Recent trends in sedentary time: A systematic literature review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczykiewicz, B.; Banik, A.; Knoll, N.; Keller, J.; Hohl, D.H.; Rosinczuk, J.; Luszczynska, A. Sedentary behaviors and anxiety among children, adolescents and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, N.; Healy, G.N.; Dempsey, P.C.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Clark, B.K.; Goode, A.D.; Koorts, H.; Ridgers, N.D.; Hadgraft, N.T.; et al. Sedentary Behavior and Public Health: Integrating the Evidence and Identifying Potential Solutions. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaddad, P.; Pemde, H.K.; Basu, S.; Dhankar, M.; Rajendran, S. Relationship of physical activity with body image, self esteem sedentary lifestyle, body mass index and eating attitude in adolescents: A cross-sectional observational study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeng, S.-J.; Han, C.-K. The Impact of Body Image Distortion on Depression in Youths: Focusing on the Mediating Effects of Stress. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2017, 37, 238–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson Jones, D. Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.J. Effect of body image distortion on mental health in adolescents. J. Health Inform. Stat. 2018, 43, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebar, W.R.; Canhin, D.S.; Colognesi, L.A.; Morano, A.E.v.A.; Silva, D.T.; Christofaro, D.G. Body dissatisfaction and its association with domains of physical activity and of sedentary behavior in a sample of 15,632 adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2021, 33, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, S.; Zaccagni, L.; Rinaldo, N.; Mauro, M.; Grigoletto, A.; Maietta Latessa, P.; Marini, S. Body image perception in high school students: The relationship with gender, weight status, and physical activity. Children 2023, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Svansdottir, E.; Sigurdsson, H.; Arnarsson, A.; Ommundsen, Y.; Arngrimsson, S.; Sveinsson, T.; Johannsson, E. Different factors associate with body image in adolescence than in emerging adulthood: A gender comparison in a follow-up study. Health Psychol. Rep. 2018, 6, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, H.; Koh, S.B.; Kim, H.C. Trends in the effects of socioeconomic position on physical activity levels and sedentary behavior among Korean adolescents. Epidemiol. Health 2023, 45, e2023085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Park, S.; Khang, Y.-H.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey (KYRBS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1076–1076e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.S.; Minatto, G.; Bandeira, A.d.S.; Santos, P.C.d.; Sousa, A.C.F.C.d.; Barbosa Filho, V.C. Sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: An update of the systematic review of the Brazil’s Report Card. Rev. Bras. De Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2021, 23, e82645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; Shin, D.W. Association of Body Image Distortion with Smartphone Dependency and Usage Time in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Korean Youth Study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2024, 46, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, R.; Lee, J.T.; Kim, J.; Song, S.; Kim, S.; Oh, H. Association of Smartphone Use With Body Image Distortion and Weight Loss Behaviors in Korean Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2213237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H.; Oh, Y.H. Sedentary lifestyle: Overview of updated evidence of potential health risks. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2020, 41, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, J.M. Body image distortion and three types of weight loss behaviors among nonoverweight girls in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.C.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Marquez, D.X.; Buman, M.P.; Napolitano, M.A.; Jakicic, J.; Fulton, J.E.; Tennant, B.L. Physical activity promotion: Highlights from the 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélair, M.-A.; Kohen, D.E.; Kingsbury, M.; Colman, I. Relationship between leisure time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and symptoms of depression and anxiety: Evidence from a population-based sample of Canadian adolescents. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.-H.; Jun, M.-K. Factors affecting body image distortion in adolescents. Children 2022, 9, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Choue, R. Relationships of body image, body stress and eating attitude, and dietary quality in middle school girls based on their BMI. Korean J. Nutr. 2010, 43, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Braithwaite, R.; Biddle, S.J.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Atkin, A.J. Associations between sedentary behaviour and physical activity in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihill, G.F.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Associations between sedentary behavior and self-esteem in adolescent girls from schools in low-income communities. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2013, 6, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-López, J.P.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; Biosca, M.; Moreno, L.A. Sedentary behaviour and obesity development in children and adolescents. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 18, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forney, K.J.; Keel, P.K.; O’Connor, S.; Sisk, C.; Burt, S.A.; Klump, K.L. Interaction of hormonal and social environments in understanding body image concerns in adolescent girls. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 109, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, C.; Hevey, D. Processing body image on social media: Gender differences in adolescent boys’ and girls’ agency and active coping. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.-M.; Trost, S.G.; Howard, S.J.; Batterham, M.; Cliff, D.; Salmon, J.; Okely, A.D. Evaluation of an intervention to reduce adolescent sitting time during the school day: The ‘Stand Up for Health’randomised controlled trial. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernström, M.; Heiland, E.G.; Kjellenberg, K.; Ponten, M.; Tarassova, O.; Nyberg, G.; Helgadottir, B.; Ekblom, M.M.; Ekblom, Ö. Effects of prolonged sitting and physical activity breaks on measures of arterial stiffness and cortisol in adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraml, K.; Perski, A.; Grossi, G.; Simonsson-Sarnecki, M. Stress symptoms among adolescents: The role of subjective psychosocial conditions, lifestyle, and self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The relationship between appearance-related stress and internalizing problems in South Korean adolescent girls. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2012, 40, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total | Weekly Average Daily Sedentary Time | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–240 min/d | 241–300 min/d | 301–360 min/d | ≥361 min/d | |||||||

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Male | 76,776 | 24,424 | (31.8) | 14,197 | (18.5) | 14,575 | (19.0) | 23,580 | (30.7) | |

| Female | 73,249 | 16,204 | (22.1) | 13,627 | (18.6) | 15,657 | (21.4) | 27,761 | (37.9) | |

| School grade | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Middle school | 81,692 | 25,772 | (31.6) | 16,520 | (20.2) | 16,073 | (19.7) | 23,327 | (28.5) | |

| High school | 68,333 | 14,856 | (21.7) | 11,304 | (16.5) | 14,159 | (20.8) | 28,014 | (41.0) | |

| Academic achievement | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 58,015 | 13,051 | (22.5) | 10,675 | (18.4) | 12,511 | (21.6) | 21,778 | (37.5) | |

| Middle | 45,370 | 12,406 | (27.3) | 8442 | (18.6) | 9123 | (20.1) | 15,399 | (34.0) | |

| Low | 46,640 | 15,171 | (32.5) | 8707 | (18.7) | 8598 | (18.4) | 14,164 | (30.8) | |

| Household income | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 62,362 | 16,405 | (26.3) | 11,337 | (18.2) | 12,301 | (19.7) | 22,319 | (35.8) | |

| Middle | 70,857 | 19,281 | (27.2) | 13,319 | (18.8) | 14,638 | (20.7) | 23,619 | (33.3) | |

| Low | 16,806 | 4942 | (29.4) | 3168 | (18.5) | 3293 | (19.6) | 5403 | (32.5) | |

| Living with parents | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 143,279 | 38,917 | (27.2) | 26,794 | (18.7) | 28,989 | (20.2) | 48,579 | (33.9) | |

| No | 6746 | 1711 | (25.4) | 1030 | (15.3) | 1243 | (18.4) | 2762 | (40.9) | |

| Regular breakfast | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 116,319 | 31,157 | (26.8) | 21,695 | (18.6) | 23,661 | (20.4) | 39,806 | (34.2) | |

| No | 33,706 | 9471 | (28.1) | 6129 | (18.2) | 6571 | (19.5) | 11,535 | (34.2) | |

| Fast food consumption | 0.1597 | |||||||||

| Frequent | 125,049 | 33,762 | (27.0) | 23,256 | (18.6) | 25,288 | (20.2) | 42,743 | (34.2) | |

| Non-frequent | 24,976 | 6866 | (27.5) | 4568 | (18.3) | 4944 | (19.8) | 8598 | (34.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.6818 | |||||||||

| Yes | 48,914 | 13,295 | (27.2) | 9131 | (18.7) | 9810 | (20.1) | 16,678 | (34.0) | |

| No | 101,111 | 27,333 | (27.0) | 18,693 | (18.5) | 20,422 | (20.2) | 34,663 | (34.3) | |

| Smoking | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 12,934 | 4119 | (31.8) | 2449 | (18.9) | 2429 | (18.8) | 3937 | (30.5) | |

| No | 137,091 | 36,509 | (26.6) | 25,375 | (18.5) | 27,803 | (20.3) | 47,404 | (34.6) | |

| Perceived stress | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 123,150 | 31,929 | (25.9) | 22,607 | (18.4) | 24,958 | (20.3) | 43,656 | (35.4) | |

| Low | 26,875 | 8699 | (32.4) | 5217 | (19.4) | 5274 | (19.6) | 7685 | (28.6) | |

| Body mass index | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Underweight | 34,399 | 9582 | (27.9) | 6512 | (18.9) | 7026 | (20.4) | 11,279 | (32.8) | |

| Normal | 90,074 | 24,175 | (26.8) | 16,745 | (18.6) | 18,104 | (20.1) | 31,050 | (34.5) | |

| Overweight | 25,552 | 6871 | (26.9) | 4567 | (17.9) | 5102 | (20.0) | 9012 | (35.2) | |

| Body image distortion | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| No | 110,303 | 30,389 | (27.5) | 20,298 | (18.4) | 22,187 | (20.1) | 37,429 | (34.0) | |

| Yes | 39,722 | 10,239 | (25.8) | 7526 | (18.9) | 8045 | (20.2) | 13,912 | (35.1) | |

| Characteristic | Total | Weekly Average Daily Sedentary Time for Educational Purposes | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–240 min/d | 241–360 min/d | 361–480 min/d | ≥481 min/d | |||||||

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Male | 76,776 | 22,075 | (28.7) | 16,806 | (21.9) | 16,616 | (21.6) | 21,279 | (27.8) | |

| Female | 73,249 | 12,586 | (17.2) | 13,690 | (18.7) | 18,710 | (25.5) | 28,263 | (38.6) | |

| School grade | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Middle school | 81,692 | 22,017 | (27.0) | 18,425 | (22.5) | 21,075 | (25.8) | 20,175 | (24.7) | |

| High school | 68,333 | 12,644 | (18.5) | 12,071 | (17.7) | 14,251 | (20.8) | 29,367 | (43.0) | |

| Academic achievement | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 58,015 | 9742 | (16.8) | 10,005 | (17.2) | 14,166 | (24.5) | 24,102 | (41.5) | |

| Middle | 45,370 | 10,626 | (23.4) | 8913 | (19.6) | 10,920 | (24.1) | 14,911 | (32.9) | |

| Low | 46,640 | 14,293 | (30.6) | 11,578 | (24.8) | 10,240 | (22.0) | 10,529 | (22.6) | |

| Household income | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 62,362 | 13,545 | (21.7) | 11,525 | (18.5) | 14,100 | (22.6) | 23,192 | (37.2) | |

| Middle | 70,857 | 16,646 | (23.5) | 14,992 | (21.2) | 17,244 | (24.3) | 21,975 | (31.0) | |

| Low | 16,806 | 4470 | (26.6) | 3979 | (23.7) | 3982 | (23.7) | 4375 | (26.0) | |

| Living with parents | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 143,279 | 33,183 | (23.2) | 29,271 | (20.4) | 34,105 | (23.8) | 46,720 | (32.6) | |

| No | 6746 | 1478 | (21.9) | 1225 | (18.2) | 1221 | (18.1) | 2822 | (41.8) | |

| Regular breakfast | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 116,319 | 26,087 | (22.4) | 23,319 | (20.1) | 27,538 | (23.7) | 39,375 | (33.8) | |

| No | 33,706 | 8574 | (25.4) | 7177 | (21.3) | 7788 | (23.1) | 10,167 | (30.2) | |

| Fast food consumption | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Frequent | 125,049 | 29,052 | (23.2) | 25,587 | (20.5) | 29,635 | (23.7) | 40,775 | (32.6) | |

| Non-frequent | 24,976 | 5609 | (22.5) | 4909 | (19.6) | 5691 | (22.8) | 8767 | (35.1) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 48,914 | 11,864 | (24.2) | 10,694 | (21.7) | 11,087 | (22.7) | 15,269 | (31.2) | |

| No | 101,111 | 22,797 | (22.5) | 19,802 | (19.6) | 24,239 | (24.0) | 34,273 | (33.9) | |

| Smoking | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 12,934 | 3756 | (29.0) | 3125 | (24.2) | 2727 | (21.1) | 3326 | (25.7) | |

| No | 137,091 | 30,905 | (22.5) | 27,371 | (20.0) | 32,599 | (23.8) | 46,216 | (33.7) | |

| Perceived stress | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 123,150 | 27,277 | (22.2) | 24,462 | (19.9) | 28,993 | (23.5) | 42,418 | (34.4) | |

| Low | 26,875 | 7384 | (27.5) | 6034 | (22.4) | 6333 | (23.6) | 7124 | (26.5) | |

| Body mass index | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Underweight | 34,399 | 7947 | (23.1) | 7165 | (20.8) | 8465 | (24.6) | 10,822 | (31.5) | |

| Normal | 90,074 | 20,317 | (22.5) | 17,892 | (19.9) | 21,145 | (23.5) | 30,720 | (34.1) | |

| Overweight | 25,552 | 6397 | (25.0) | 5439 | (21.3) | 5716 | (223.4) | 8000 | (31.3) | |

| Body image distortion | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| No | 110,303 | 26,097 | (23.6) | 22,576 | (20.5) | 25,553 | (23.2) | 36,077 | (32.7) | |

| Yes | 39,722 | 8564 | (21.6) | 7920 | (19.9) | 9773 | (24.6) | 13,465 | (33.9) | |

| Characteristic | Total | Weekly Average Daily Sedentary Time for Non-Educational Purposes | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–120 min/d | 121–180 min/d | 181–300 min/d | ≥301 min/d | |||||||

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Male | 76,776 | 13,890 | (18.1) | 16,937 | (22.1) | 24,603 | (32.0) | 21,346 | (27.8) | |

| Female | 73,249 | 14,575 | (19.9) | 16,853 | (23.0) | 23,260 | (31.8) | 18,561 | (25.3) | |

| School grade | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Middle school | 81,692 | 15,212 | (18.6) | 17,553 | (21.5) | 26,265 | (32.2) | 22,662 | (27.7) | |

| High school | 68,333 | 13,253 | (19.4) | 16,237 | (23.8) | 21,598 | (31.6) | 17,245 | (25.2) | |

| Academic achievement | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 58,015 | 13,046 | (22.5) | 14,550 | (25.1) | 18,391 | (31.7) | 12,028 | (20.7) | |

| Middle | 45,370 | 8133 | (18.0) | 10,464 | (23.0) | 14,933 | (32.9) | 11,840 | (26.1) | |

| Low | 46,640 | 7286 | (15.6) | 8776 | (18.8) | 14,539 | (31.2) | 16,039 | (34.4) | |

| Household income | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| High | 62,362 | 12,954 | (20.8) | 14,999 | (24.0) | 19,742 | (31.7) | 14,667 | (23.5) | |

| Middle | 70,857 | 12,512 | (17.7) | 15,504 | (21.9) | 22,970 | (32.4) | 19,871 | (28.0) | |

| Low | 16,806 | 2999 | (17.8) | 3287 | (19.6) | 5151 | (30.7) | 5369 | (31.9) | |

| Living with parents | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 143,279 | 26,787 | (18.7) | 32,258 | (22.5) | 45,899 | (32.0) | 38,335 | (26.8) | |

| No | 6746 | 1678 | (24.9) | 1532 | (22.7) | 1964 | (29.1) | 1572 | (23.3) | |

| Regular breakfast | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 116,319 | 22,418 | (19.3) | 26,981 | (23.2) | 37,387 | (32.1) | 29,533 | (25.4) | |

| No | 33,706 | 6047 | (17.9) | 6809 | (20.2) | 10,476 | (31.1) | 10,374 | (30.8) | |

| Fast food consumption | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Frequent | 125,049 | 22,785 | (18.2) | 28,060 | (22.4) | 40,242 | (32.2) | 33,962 | (27.2) | |

| Non-frequent | 24,976 | 5680 | (22.8) | 5730 | (22.9) | 7621 | (30.5) | 5945 | (23.8) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 48,914 | 8595 | (17.6) | 10,330 | (21.1) | 15,540 | (31.8) | 14,449 | (29.5) | |

| No | 101,111 | 19,870 | (19.6) | 23,460 | (23.2) | 32,323 | (32.0) | 25,458 | (25.2) | |

| Smoking | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Yes | 12,934 | 2377 | (18.4) | 2588 | (20.0) | 3906 | (30.2) | 4063 | (31.4) | |

| No | 137,091 | 26,088 | (19.0) | 31,202 | (22.8) | 43,957 | (32.1) | 35,844 | (26.1) | |

| Perceived stress | 0.0006 | |||||||||

| High | 123,150 | 23,127 | (18.8) | 27,827 | (22.6) | 39,342 | (31.9) | 32,854 | (26.7) | |

| Low | 26,875 | 5338 | (19.9) | 5963 | (22.2) | 8521 | (31.7) | 7053 | (26.2) | |

| Body mass index | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Underweight | 34,399 | 6736 | (19.6) | 7634 | (22.2) | 10,906 | (31.7) | 9123 | (26.5) | |

| Normal | 90,074 | 17,571 | (19.5) | 20,809 | (23.1) | 28,721 | (31.9) | 22,973 | (25.5) | |

| Overweight | 25,552 | 4158 | (16.3) | 5347 | (20.9) | 8236 | (32.2) | 7811 | (30.6) | |

| Body image distortion | 0.0059 | |||||||||

| No | 110,303 | 20,724 | (18.8) | 24,971 | (22.6) | 35,327 | (32.0) | 29,281 | (26.6) | |

| Yes | 39,722 | 7741 | (19.5) | 8819 | (22.2) | 12,536 | (31.6) | 10,626 | (26.7) | |

| Sedentary Time (min/d) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) for Body Image Distortion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Purpose | Educational Purposes | Non-Educational Purposes | ||

| Total | Low | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | |

| Male | Low | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | |

| Female | Low | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 1.06 (1.02–1.09) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, W.; Lee, M.-J. Association Between Sedentary Behavior and Body Image Distortion Among Korean Adolescents Considering Sedentary Purpose. Children 2026, 13, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010020

Park S, Lee H, Lee W, Lee M-J. Association Between Sedentary Behavior and Body Image Distortion Among Korean Adolescents Considering Sedentary Purpose. Children. 2026; 13(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010020

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Suin, Heesoo Lee, Wanhyung Lee, and Mi-Jeong Lee. 2026. "Association Between Sedentary Behavior and Body Image Distortion Among Korean Adolescents Considering Sedentary Purpose" Children 13, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010020

APA StylePark, S., Lee, H., Lee, W., & Lee, M.-J. (2026). Association Between Sedentary Behavior and Body Image Distortion Among Korean Adolescents Considering Sedentary Purpose. Children, 13(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010020