Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review Focused on Preterm Birth Phenotype and Specific Lengths of Gestation

Highlights

- •

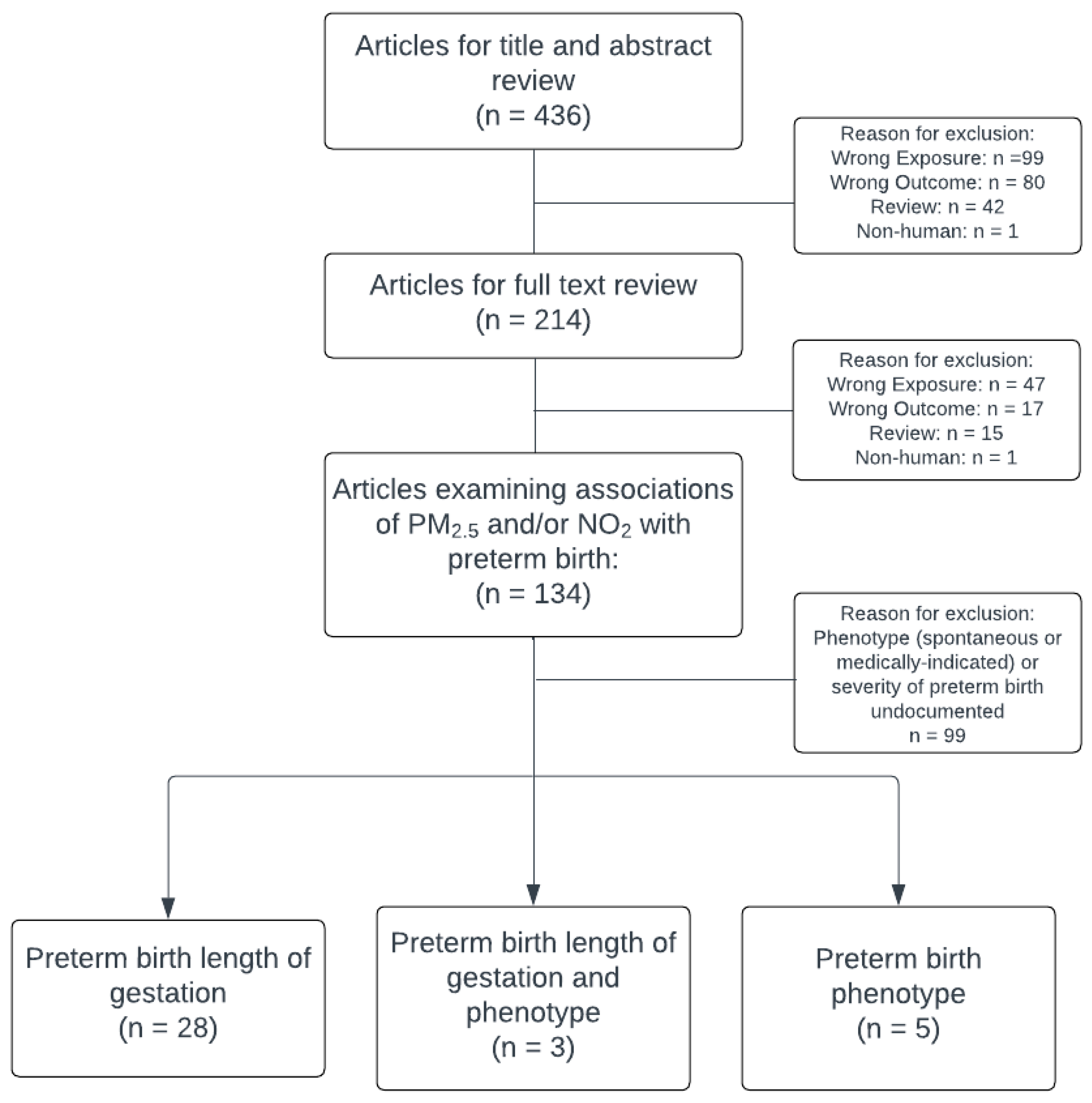

- While there have been over 100 studies of ambient PM2.5 and NO2 with preterm birth since 2011, only one in four studies reports on specific lengths of gestation.

- •

- Even fewer (one in fifteen) report on specific preterm birth phenotypes (i.e., spontaneous or medically indicated).

- •

- Preterm birth is heterogeneous with respect to lengths of gestation as well as the etiology, but is often analyzed as a single outcome in environmental health studies.

- •

- Future studies of air pollution and other environmental exposures with preterm birth should disaggregate preterm birth phenotypes to shed light on potential mechanisms and to focus prevention strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Scope of Review

2.2. Research Question

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

2.4. Study Categorization

3. Results

3.1. Studies Reporting PTB Phenotype (sPTB or mPTB)

3.2. Studies Reporting Positive Findings with PTB Specific Lengths of Gestation

3.3. Studies Reporting Positive Findings with Specific Lengths of Gestation—PM2.5

3.4. Studies Reporting Positive Findings with Specific PTB Lengths of Gestation—NO2

3.5. Studies Reporting Mixed Findings with Specific PTB Lengths of Gestation—PM2.5

3.6. Studies Reporting Mixed Findings with Specific PTB Lengths of Gestation—NO2

3.7. Studies Reporting Null Findings of PM2.5 and NO2 with Specific PTB Lengths of Gestation

3.8. Studies Reporting Both PTB Phenotype and Specific PTB Lengths of Gestation

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Dearth of Information Regarding PTB Phenotype

4.2. Reasons for Variation in Findings in Studies That Examine PTB Phenotype or Specific Lengths of Gestation

4.2.1. Duration and Timing of Exposure

4.2.2. Difference in Air Pollution Exposures and Shape of the Relationship

4.2.3. Spatial Units

4.2.4. Population and Analytic Approach

4.3. Conclusion and Implications for Future Research and Public Health

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aHR | adjusted hazard ratio |

| PTB | preterm birth |

| sPTB | spontaneous preterm birth |

| mPTB | medical preterm birth |

| PM2.5 | particulate matter |

| NO2 | nitrogen dioxide |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| aOR | association odds ratio |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| RR RD | relative risk risk difference |

References

- Veber, T.; Dahal, U.; Lang, K.; Orru, K.; Orru, H. Industrial Air Pollution Leads to Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Systematized Review of Different Exposure Metrics and Health Effects in Newborns. Public Health Rev. 2022, 43, 1604775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Reducing Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, e40–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumberg, H.L.; Karr, C.J. Ambient Air Pollution: Health Hazards to Children. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2021051484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V.; Vintzileos, A.M. Epidemiology of Preterm Birth and Its Clinical Subtypes. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006, 19, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preterm Birth. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Chang, H.H.; Warren, J.L.; Darrow, L.A.; Reich, B.J.; Waller, L.A. Assessment of Critical Exposure and Outcome Windows in Time-to-Event Analysis with Application to Air Pollution and Preterm Birth Study. Biostatistics 2014, 16, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neophytou, A.M.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.A.; Goin, D.E.; Darwin, K.C.; Casey, J.A. Educational Note: Addressing Special Cases of Bias That Frequently Occur in Perinatal Epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieb, D.M.; Chen, L.; Eshoul, M.; Judek, S. Ambient Air Pollution, Birth Weight and Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2012, 117, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melody, S.; Wills, K.; Knibbs, L.D.; Ford, J.; Venn, A.; Johnston, F. Adverse Birth Outcomes in Victoria, Australia in Association with Maternal Exposure to Low Levels of Ambient Air Pollution. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gat, R.; Kachko, E.; Kloog, I.; Erez, O.; Yitshak-Sade, M.; Novack, V.; Novack, L. Differences in Environmental Factors Contributing to Preterm Labor and PPROM—Population Based Study. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escoto, K.M.; Mullin, A.M.; Ledyard, R.; Rovit, E.; Yang, N.; Tripathy, S.; Burris, H.H.; Clougherty, J.E. Benzene and NO2 Exposure during Pregnancy and Preterm Birth in Two Philadelphia Hospitals, 2013–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Fan, K.; Bao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Kan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, J.; Ying, H. Prenatal Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and the Risk of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: A Population-Based Cohort Study of Twins. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1002824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.F.; Li, C.; Xu, J.J.; Zhou, F.Y.; Li, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.T.; Huang, H.F. Associations between Short-Term and Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter and Preterm Birth. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Jalaludin, B.; Hajat, S.; Morgan, G.G.; Meissner, K.; Kaldor, J.; Green, D.; Jegasothy, E. Acute Air Pollution and Temperature Exposure as Independent and Joint Triggers of Spontaneous Preterm Birth in New South Wales, Australia: A Time-to-Event Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1220797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Bobb, J.F.; Ito, K.; Savitz, D.A.; Elston, B.; Shmool, J.L.C.; Dominici, F.; Ross, Z.; Clougherty, J.E.; Matte, T. Ambient Fine Particulate Matter, Nitrogen Dioxide, and Preterm Birth in New York City. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, X.; Kan, H.; Zhang, J. Residential Greenspace Counteracts PM2.5 on the Risks of Preterm Birth Subtypes: A Multicenter Study. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Martinez, V.; Chan-Golston, A.M. Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Study in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2022, 36, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, Z.K.; Oehlert, J.W.; Eskenazi, B.; Shaw, G.M.; Balmes, J.R.; Padula, A.M. The Relationship between Air Pollutants and Maternal Socioeconomic Factors on Preterm Birth in California Urban Counties. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, P.; Ilango, S.; Bruckner, T.A.; Wang, Q.; Basu, R.; Benmarhnia, T. Ambient Fine Particulate Matter and Preterm Birth in California: Identification of Critical Exposure Windows. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, R.; Pearson, D.; Ebisu, K.; Malig, B. Association between PM 2.5 and PM 2.5 Constituents and Preterm Delivery in California, 2000-2006. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2017, 31, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Hu, H.; Roth, J.; Kan, H.; Xu, X. Associations between Residential Proximity to Power Plants and Adverse Birth Outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 182, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Hu, H.; Roussos-Ross, D.; Haidong, K.; Roth, J.; Xu, X. The Effects of Air Pollution on Adverse Birth Outcomes. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappazzo, K.M.; Daniels, J.L.; Messer, L.C.; Poole, C.; Lobdell, D.T. Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Risk of Preterm Birth among Women in New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, 2000–2005. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, H.M.; Ghaji, N.; Mbah, A.K.; Alio, A.P.; August, E.M.; Boubakari, I. Particulate Pollutants and Racial/Ethnic Disparity in Feto-Infant Morbidity Outcomes. Matern. Child. Health J. 2012, 16, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy-Bushrow, A.E.; Burmeister, C.; Lamerato, L.; Lemke, L.D.; Mathieu, M.; O’Leary, B.F.; Sperone, F.G.; Straughen, J.K.; Reiners, J.J. Prenatal Airshed Pollutants and Preterm Birth in an Observational Birth Cohort Study in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Environ. Res. 2020, 189, 109845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, O.; Hu, J.; Li, L.; Kleeman, M.J.; Bartell, S.M.; Cockburn, M.; Escobedo, L.; Wu, J. A Statewide Nested Case–Control Study of Preterm Birth and Air Pollution by Source and Composition: California, 2001–2008. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, V.; Díaz, J.; Ortiz, C.; Carmona, R.; Sáez, M.; Linares, C. Short Term Effect of Air Pollution, Noise and Heat Waves on Preterm Births in Madrid (Spain). Environ. Res. 2016, 145, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, A.M.; Mortimer, K.M.; Tager, I.B.; Hammond, S.K.; Lurmann, F.W.; Yang, W.; Stevenson, D.K.; Shaw, G.M. Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Risk of Preterm Birth in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 888–895.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wilhelm, M.; Chung, J.; Ritz, B. Comparing Exposure Assessment Methods for Traffic-Related Air Pollution in an Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, M.; Lecoeuvre, A.; Cuny, D.; Subtil, D.; Chevalier, G.; Ficheur, G.; Occelli, F.; Garabedian, C. The Association between the Incidence of Preterm Birth and Overall Air Pollution: A Nationwide, Fine-Scale, Spatial Study in France from 2012 to 2018. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 120013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padula, A.M.; Yang, W.; Lurmann, F.W.; Balmes, J.; Hammond, S.K.; Shaw, G.M. Prenatal Exposure to Air Pollution, Maternal Diabetes and Preterm Birth. Environ. Res. 2019, 170, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendola, P.; Wallace, M.; Hwang, B.S.; Liu, D.; Robledo, C.; Männistö, T.; Sundaram, R.; Sherman, S.; Ying, Q.; Grantz, K.L. Preterm Birth and Air Pollution: Critical Windows of Exposure for Women with Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 432–440.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieb, D.M.; Chen, L.; Beckerman, B.S.; Jerrett, M.; Crouse, D.L.; Omariba, D.W.R.; Peters, P.A.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Burnett, R.T.; et al. Associations of Pregnancy Outcomes and PM2.5 in a National Canadian Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibben, C.; Clemens, T. Place of Work and Residential Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Birth Outcomes in Scotland, Using Geographically Fine Pollution Climate Mapping Estimates. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.A.; Yang, W.; Lurmann, F.; Hammond, S.K.; Shaw, G.M.; Padula, A.M. Air Pollution, Maternal Hypertensive Disorders, and Preterm Birth. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 3, e062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, D.; Peng, Z.; et al. Composition of Fine Particulate Matter and Risk of Preterm Birth: A Nationwide Birth Cohort Study in 336 Chinese Cities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zou, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, R.; Jia, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, H.; Yuan, N.; et al. Maternal Exposures to Fine and Ultrafine Particles and the Risk of Preterm Birth from a Retrospective Study in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 151488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, D.; Gao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Yu, Z.; Huang, C. Interaction Effects of Night-Time Temperature and PM2.5 on Preterm Birth in Huai River Basin, China. Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Guo, Y.; Abramson, M.J.; Williams, G.; Li, S. Exposure to Low Concentrations of Air Pollutants and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Brisbane, Australia, 2003–2013. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lin, H.; Li, H.; Jin, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, P.; Xu, N.; Xu, S.; Fang, J.; Wu, S.; et al. Exposure of Ambient PM2.5 during Gametogenesis Period Affects the Birth Outcome: Results from the Project ELEFANT. Environ. Res. 2023, 220, 115204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Li, W.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Xu, W.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Jiang, M.; et al. Third Trimester as the Susceptibility Window for Maternal PM2.5 Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Nationwide Surveillance-Based Association Study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ming, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yin, P. Association between Maternal Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and the Risk of Preterm Birth: A Birth Cohort Study in Chongqing, China, 2015–2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, J.J.; He, Y.C.; Chen, L.; Dennis, C.L.; Huang, H.F.; Wu, Y.T. Effects of Acute Ambient Pollution Exposure on Preterm Prelabor Rupture of Membranes: A Time-Series Analysis in Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, C.; Ren, Z.; Feng, H.; Zuo, S.; Hao, J.; Liao, J.; Zou, Y.; Ma, L. Maternal PM2.5 Exposure Triggers Preterm Birth: A Cross-Sectional Study in Wuhan, China. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Byun, H.M.; Hui Li, P.; Deng, F.; Guo, X.; Guo, L.; Wu, S. Associations of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes with High Ambient Air Pollution Exposure: Results from the Project ELEFANT. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.; Kuper, S.G.; Steele, R.; Sievert, R.A.; Tita, A.T.; Harper, L.M. Outcomes of Medically Indicated Preterm Births Differ by Indication. Am. J. Perinatol. 2018, 35, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, J.; Yang, M.; Sun, P.; Gong, Y.; Chai, J.; Zhang, J.; Afrim, F.-K.; Dong, W.; Sun, R.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Air Pollution and the Risk of Preterm Birth in Rural Population of Henan Province. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieb, D.M.; Chen, L.; Hystad, P.; Beckerman, B.S.; Jerrett, M.; Tjepkema, M.; Crouse, D.L.; Omariba, D.W.; Peters, P.A.; van Donkelaar, A.; et al. A National Study of the Association between Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Canada, 1999-2008. Environ. Res. 2016, 148, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J.P. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences and Prevention. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, M.S.; Lintao, R.C.V.; Severino, M.E.L.; Tantengco, O.A.G.; Menon, R. Spontaneous Preterm Birth: Involvement of Multiple Feto-Maternal Tissues and Organ Systems, Differing Mechanisms, and Pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1015622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye-Petersen, O.M. The Placenta in Preterm Birth. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008, 61, 1261–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplin, M.S.; Manuck, T.A.; Varner, M.W.; Christensen, B.; Biggio, J.; Bukowski, R.; Parry, S.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Andrews, W.; et al. Cluster Analysis of Spontaneous Preterm Birth Phenotypes Identifies Potential Associations among Preterm Birth Mechanisms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 429.e1–429.e4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutquin, J. Classification and Heterogeneity of Preterm Birth. BJOG 2003, 110, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananth, C.V.; Vintzileos, A.M. Medically Indicated Preterm Birth: Recognizing the Importance of the Problem. Clin. Perinatol. 2008, 35, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, T.; Kacerovsky, M.; Jacobsson, B. Risk Factors for Spontaneous Preterm Delivery. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuck, T.A.; Esplin, M.S.; Biggio, J.; Bukowski, R.; Parry, S.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Varner, M.W.; Andrews, W.; Saade, G.; et al. The Phenotype of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: Application of a Clinical Phenotyping Tool. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 487.e1–487.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.; Cavoretto, P.I.; Barros, F.C.; Romero, R.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Kennedy, S.H. Etiologically Based Functional Taxonomy of the Preterm Birth Syndrome. Clin. Perinatol. 2024, 51, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, F.C.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Victora, C.G.; Noble, J.A.; Pang, R.; Iams, J.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Lambert, A.; Kramer, M.S.; et al. The Distribution of Clinical Phenotypes of Preterm Birth Syndrome. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.C.; Roberts, J.M.; Catov, J.M.; Talbott, E.O.; Ritz, B. First Trimester Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution, Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Allegheny County, PA. Matern. Child. Health J. 2013, 17, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kase, B.A.; Carreno, C.A.; Blackwell, S.C.; Sibai, B.M. The Impact of Medically Indicated and Spontaneous Preterm Birth among Hypertensive Women. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, H.; Melamed, N.; Davis, B.M.; Hasan, H.; Mawjee, K.; Barrett, J.; McDonald, S.D.; Geary, M.; Ray, J.G. Impact of Diabetes, Obesity and Hypertension on Preterm Birth: Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; Culhane, J.F.; Iams, J.D.; Romero, R. Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm Birth. Lancet 2008, 371, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmer, J.; Hardman, I.; Shimshack, J.; Voorheis, J. Disparities in PM2.5 Air Pollution in the United States. Science 2020, 369, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessum, C.W.; Paolella, D.A.; Chambliss, S.E.; Apte, J.S.; Hill, J.D.; Marshall, J.D. PM2.5 Polluters Disproportionately and Systemically Affect People of Color in the United States. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Yang, X.; Liang, F.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Shen, C.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and Hypertension Incidence in China the China-PAR Cohort Study. Hypertension 2019, 73, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.; Donahue, N.M.; Bernardo-Bricker, A.; Rogge, W.F.; Robinson, A.L. Insights into the Primary-Secondary and Regional-Local Contributions to Organic Aerosol and PM2.5 Mass in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 7414–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, R.; Wang, W. Concentrations, Correlations and Chemical Species of PM2.5/PM10 Based on Published Data in China: Potential Implications for the Revised Particulate Standard. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.L.; Dominici, F.; Ebisu, K.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M. Spatial and Temporal Variation in PM2.5 Chemical Composition in the United States for Health Effects Studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Peng, R.D. The Impact of Wildfire Smoke on Compositions of Fine Particulate Matter by Ecoregion in the Western US. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasovich Southworth, E.; Qiu, M.; Gould, C.F.; Kawano, A.; Wen, J.; Heft-Neal, S.; Kilpatrick Voss, K.; Lopez, A.; Fendorf, S.; Burney, J.A.; et al. The Influence of Wildfire Smoke on Ambient PM 2.5 Chemical Species Concentrations in the Contiguous US. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 2961–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Liu, Y.; Chatfield, R.B. Neighborhood-Scale Ambient NO2 Concentrations Using TROPOMI NO2 Data: Applications for Spatially Comprehensive Exposure Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, A.C.; Arfer, K.B.; Rush, J.; Lyapustin, A.; Kloog, I. XIS-PM2.5: A Daily Spatiotemporal Machine-Learning Model for PM2.5 in the Contiguous United States. Environ. Res. 2025, 271, 120948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zeger, S.L. On the Equivalence of Case-Crossover and Time Series Methods in Environmental Epidemiology. Biostatistics 2007, 8, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclure, M. The Case-Crossover Design: A Method for Studying Transient Effects on the Risk of Acute Events. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión, D.; Rush, J.; Colicino, E.; Just, A.C. The Case-Crossover Design Under Changing Baseline Outcome Risk: A Simulation of Ambient Temperature and Preterm Birth. Epidemiology 2022, 33, e14–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.H.; Reich, B.J.; Miranda, M.L. A Spatial Time-to-Event Approach for Estimating Associations Between Air Pollution and Preterm Birth. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2013, 62, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFranco, E.; Hall, E.; Hossain, M.; Chen, A.; Haynes, E.N.; Jones, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, L.; Muglia, L. Air Pollution and Stillbirth Risk: Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter during Pregnancy Is Associated with Fetal Death. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm Cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: sPTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: mPTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melody et al., 2020 [9] | PM2.5 | 18,457/285,595 | Victoria, Australia 2012–2015, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR of annual exposure (1.3 µg/m3), median 7.1 µg/m3 | RR 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | |

| Gat et al., 2021 [10] | PM2.5 | 5026/63,027 | Beersheba Israel 2003–2013, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (3.8 µg/m3), median 20.3 | Jewish population RR 1.014 (0.979, 1.050) Bedouin population RR 1.005 (0.976, 1.035) | |

| Singh et al., 2023 [14] | PM2.5 | 38,900/1,354,919 | New South Wales, Australia 2001–2019, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 µg/m3, median 6.8 µg/m3 | HRs ranging from 0.86 (0.84, 1.4) to 8.98 (0.97, 1.00) for sPTB overall, extremely sPTB, very sPTB, moderate-to-late sPTB | |

| Johnson et al., 2016 [15] | PM2.5 | 19,013/258,294 | New York City 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, median 11.5 µg/m3 for first trimester and 11.4 µg/m3 for second trimester | First trimester exposure OR 0.99 (0.90, 1.08), no association with sPTB < 32 weeks’ GA Second trimester exposure OR 0.99 (0.90, 1.09), no association with sPTB < 32 weeks’ gestation | First trimester exposure OR 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) Second trimester exposure OR 0.95 (0.84, 1.08) |

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm Cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: sPTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: mPTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melody et al., 2020 [9] | NO2 | 18,457/285,595 | Victoria, Australia 2012–2015, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR of annual exposure (3.9 ppb), median 5.6 ppb | RR 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | |

| Escoto et al., 2022 [11] | NO2 | 1708/19,169 | Philadelphia, PA 2013–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per standard deviation (2.3 ppb), mean 17.2 ppb | aOR 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | aOR 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) |

| Johnson et al., 2016 [15] | NO2 | 19,013/258,294 | New York City 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 20 ppb, median 27.1 for first trimester and 26.1 for second trimester | First trimester exposure OR 0.94 (0.87, 1.02), no association with sPTB < 32 weeks’ gestation Second trimester exposure sPTB OR 0.90 (0.83, 0.97), no association with sPTB < 32 weeks’ gestation | First trimester exposure OR 0.90 (0.81, 0.99) Second trimester exposure OR 0.89 (0.80, 0.99) |

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: sPTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: mPTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qiao et al., 2022 [12] | PM2.5 | 764/ 1515 pairs of twins | Shanghai, China 2013– 2016, Population-based Cohort (retrospective) | Per IQR (4.9 µg/m3), median 52.5 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy and 52.5 µg/m3 for second trimester | Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 0.95 (0.81, 1.11) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.48 (1.06, 2.05) | |

| Su et al., 2023 [13] | PM2.5 | 9976/ 179,385 | Shanghai, China 2014– 2020, Time-series analysis and Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, mean 43.2 µg/m3 | First trimester exposure aOR 0.987 (0.970–1.003) Second trimester exposure aOR 0.993 (0.971–1.016) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.042 (1.018–1.065) | First trimester exposure aOR 0.995 (0.968, 1.023) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.012 (0.981, 1.044) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.022 (0.993, 1.051) |

| Jiang et al., 2023 [16] | PM2.5 | 1146/ 19,900 | Shanghai, China 2015–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (9.6 µg/m3), median 49.0 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy | Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) First trimester exposure aOR 1.15 (0.89, 1.48) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.11 (0.97, 1.27) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.53 (1.17, 2.01) | Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.37 (1.10, 1.69) First trimester exposure aOR 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.91 (1.37, 2.69) |

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: Very or Extreme PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Moderate PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Late PTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ha et al., 2022 [17] | PM2.5 | 44,565/ 196,970 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2007–2015, Time-stratified case-crossover study | Per IQR (15.4–16.1 µg/m3), mean 16.8–17.1 µg/m3 in week prior to delivery | Very PTB Associated with 5–6% increased odds beginning at lag 3: OR 1.06 (1.02, 1.11) | ||

| Mekonnen et al., 2021 [18] | PM2.5 | 87,495/ 953,951 | California, USA 2007–2011, Retrospective Cohort | Per 1 µg/m3, mean 13.5 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy | Early PTB (<34 weeks) Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) First trimester exposure aOR 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) Third trimester exposure aOR 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | ||

| Sheridan et al., 2019 [19] | PM2.5 | 187,275/ 2,293,218 | California, USA 2005–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, mean 13.5 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy | Very PTB Entire pregnancy exposure aHR 1.19 (1.14, 1.25) First trimester exposure aHR 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) Second trimester exposure aHR 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) Third trimester exposure aHR 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | Entire pregnancy exposure aHR 1.11 (1.09, 1.14) First trimester exposure aHR 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) Second trimester exposure aHR 1.05 (1.03, 1.06) Third trimester exposure aHR 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | |

| Basu et al., 2017 [20] | PM2.5 | 23,265/ 231,637 | California, USA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (6.96 µg/m3), mean 18.8 µg/m3 | 12–25% increased odds for late, moderate, and very preterm deliveries. No significant association for extremely preterm deliveries. | ||

| Ha et al., 2015 [21] | PM2.5 | 39,082/ 423,719 | Florida, USA 2004–2005, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 km closer residential proximity to any power plant, mean 5.1–17.6 µg/m3 | Very PTB aOR 1.022 (1.010, 1.034) | ||

| Ha et al., 2014 [22] | PM2.5 | 39,082/ 423,719 | Florida, USA 2004–2005, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (2.6 µg/m3), median 9.9 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy, 9.6 µg/m3 for first trimester, 9.8 µg/m3 for second trimester, 10.0 µg/m3 for third trimester | Very PTB Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.082 (1.048, 1.117) First trimester exposure aOR 1.063 (1.028, 1.098) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.215 (1.177, 1.253) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.010 (0.972, 1.049) | ||

| Rappazzo et al., 2014 [23] | PM2.5 | 142,151/ 1,781,527 | Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New Jersey 2000–2005, Retrospective Cohort | Per 1 µg/m3, mean 14.5 µg/m3 | PM2.5 exposure during the 4th week of gestation Extreme PTB RD 11.8 (−6, 29.2) Very PTB RD 46 (23.2, 68.9) | PM2.5 exposure during the 4th week of gestation RD 61.1 (22.6, 99.7) | PM2.5 exposure during the 4th week of gestation RD 28.5 (−39, 95.7) |

| Salihu et al., 2012 [24] | PM2.5 | 9459/ 103,961 | Hillsborough County, Florida, USA 2000–2007, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure above median (>11.3 µg/m3) | Very PTB aOR 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | ||

| Cassidy-Bushrow et al., 2020 [25] | PM2.5 | 891/ 7961 | Detroit, MI 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 µg/m3, mean 10.7 µg/m3 | In the fully adjusted model, PM2.5 (mean change in gestational age [weeks]. 0.14 ± 0.12; p = 0.255) was not associated with gestational age at delivery. | ||

| Laurent et al., 2016 [26] | PM2.5 | 442,314/ 3,870,696 | California, USA 2001–2008, Nested case–control | Per IQR increase (6.5 µg/m3), median exposure not reported | Very PTB aOR 1.102 (1.071, 1.134) | aOR 1.138 (1.119, 1.156) | |

| Arroyo et al., 2016 [27] | PM2.5 | 24,620/ 298,705 | Madrid, Spain 2001–1009, Time series analysis | Per IQR increase (IQR not reported, mean (SD) 17.1 (7.8) µg/m3) | No association of PM2.5 with very preterm birth or extremely preterm birth from 0 to 7 days preceding birth reported | ||

| Padula et al., 2014 [28] | PM2.5 | 30,963/ 263,204 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure in the highest quartile (20.8 µg/m3) combined to the lowest three quartiles combined, mean 18.0–18.6 µg/m3 | Very PTB aOR 1.62 (1.45–1.81) Extreme PTB (24–27 weeks) aOR 1.81 (1.50–2.18) Extreme PTB (20–23 weeks) aOR 1.25 (0.95, 1.65) | aOR 1.54 (1.41, 1.68) | aOR 1.27 (1.22, 1.32) |

| Wu et al., 2011 [29] | PM2.5 | 6712/ 81,186 | Los Angeles and Orange Counties, California 1997–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Per 1 µg/m3, mean 17.3 µg/m3 | Very PTB Los Angeles County aOR 1.03 (0.81–1.30) Orange County aOR 1.33 (0.99–1.77) | ||

| Genin et al., 2022 [30] | PM2.5 | 278,817/ 5,070,262 | France 2012–2018, Cross-sectional Study | Ecological regression, relative risk of PTB and 95% credibility interval, median 9.5 µg/m3 | Very PTB RR 1.072 (1.051, 1.094) Extreme PTB RR 1.191 (1.153, 1.230) | RR 1.020 (1.012,1.028) | |

| Singh et al., 2023 [14] | PM2.5 | 38,900/ 1,354,919 | New South Wales, Austria 2001–2019, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 µg/m3, median 6.8 µg/m3 | HRs ranging from 0.86 (0.84, 1.4) to 8.98 (0.97, 1.00) for extremely sPTB, very sPTB, moderate-to-late sPTB | ||

| Johnson et al., 2016 [15] | PM2.5 | 19,013/ 258,294 | New York City 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, median 27.1 for first trimester and 26.1 for second trimester | No evidence of association of first or trimester exposure with early preterm birth. | ||

| Studies investigating effect modification by disease process or birthing parent comorbidity on relationship of PM2.5 with PTB length of gestation | |||||||

| Padula et al., 2019 [31] | PM2.5 | 28,788/ 252,205 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure in the highest quartile (17.1 µg/m3) combined to the lowest three quartiles combined, median 17.1 µg/m3 | Very PTB Without diabetes aOR 1.37 (1.25, 1.50) With diabetes aOR 1.27 (0.89, 1.81) Extreme PTB Without diabetes aOR 1.58 (1.40, 1.78) With diabetes aOR 2.44 (1.39, 4.29) | Without diabetes aOR 1.46 (1.36, 1.58) With diabetes aOR 1.35 (1.03, 1.76) | Without diabetes aOR 1.23 (1.19, 1.27) With diabetes aOR 1.19 (1.05, 1.34) |

| Mendola et al., 2016 [32] | PM2.5 | 26,144/ 223,502 | US 2002–2008 Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (4.7 µg/m3), median 11.9 µg/m3 | Preterm birth < 34 weeks’ gestation among birthing parents with asthma aOR 1.11 (1.01, 1.22) | ||

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: Very or Extreme PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Moderate PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Late PTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stieb et al., 2016 [33] | NO2 | 182,475/ 2,928,515 | Canada 1999–2008, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (11.5 ppb), median 11.9 ppb | Extreme PTB OR 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) Very PTB OR 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | OR 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | OR 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) |

| Cassidy-Bushrow et al., 2020 [25] | NO2 | 891/ 7961 | Detroit, MI 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 ppb, median 18.5 ppb | In the fully adjusted model, NO2 (mean change in gestational age [weeks] 0.11 ± 0.09; p = 0.245) was not associated with gestational age at delivery | ||

| Laurent et al., 2016 [26] | NO2 | 442,314/ 3,870,696 | California, USA 2001–2008, Nested case–control | Per IQR increase (10.0 ppb), median exposure not reported | Very PTB aOR 1.048 (1.018, 1.080) | aOR 1.077 (1.061, 1.094) | |

| Arroyo et al., 2016 [27] | NO2 | 24,620/ 298,705 | Madrid, Spain 2001–2009, Time series analysis | Per IQR increase (IQR not reported, mean (SD) 59.4 (17.9) µg/m3) | No association of NO2 with very PTB or extreme PTB from 0 to 7 days preceding birth reported | ||

| Padula et al., 2014 [28] | NO2 | 30,963/ 263,204 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure in the highest quartile (19.5 ppb) combined to the lowest three quartiles combined, mean exposure 16.8–17.7 ppb | Very PTB aOR 1.13 (1.00, 1.27) Extreme PTB (24–27 weeks) aOR 1.08 (0.88, 1.33) Extreme PTB (20–23 weeks) aOR 0.88 (0.51, 1.17) | aOR 1.13 (1.03, 1.25) | aOR 1.11 (1.06, 1.15) |

| Wu et al., 2011 [29] | NO2 | 6712/81,186 | Los Angeles and Orange Counties, California 1997–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 ppb increase, mean 24.9 ppb | Very PTB Los Angeles County aOR 1.46 (1.11, 1.92) Orange County aOR 1.43 (1.02, 2.01) | ||

| Genin et al., 2022 [30] | NO2 | 278,817/5,070,262 | France 2012–2018, Cross-sectional study | Ecological regression, relative risk of PTB and 95% credibility interval, median 8.1 µg/m3 | Very PTB RR 1.046 (1.035, 1.059) Extreme PTB RR 1.114 (1.094, 1.135) | RR 1.011 (1.006, 1.016) | |

| Dibben et al., 2015 [34] | NO2 | 1242/ 23,086 | Scotland 1994–2018, Retrospective Cohort | Per 1 µg/m3, mean 17.5 µg/m3 | Very PTB aOR 1.013 (1.00, 1.03) | aOR 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | |

| Johnson et al., 2016 [15] | NO2 | 19,013/ 258,294 | New York City 2008–2010, Retrospective Cohort | Per 20 ppb, median 27.1 for first trimester and 26.1 for second trimester | No evidence of association of first or trimester exposure with early preterm birth. | ||

| Studies investigating effect modification of disease process or birthing parent comorbidity on relationship of PM2.5 with PTB lengths of gestation. | |||||||

| Mendola et al., 2016 [32] | NOx | 26,144/223,502 | US 2002–2008 Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (24.2 ppb), median 30.9 ppb | No significant association of preterm birth < 34 weeks’ gestation among birthing parents with or without asthma | ||

| Weber et al., 2019 [35] | NO2 | 28,788/252,205 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure in the highest quartile (19.5 ppb) combined to the lowest 3 quartiles combined, median 17.3 | Very PTB Without hypertension aOR 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) With hypertension aOR 0.99 (0.78, 1.26) Extreme PTB Without hypertension aOR 1.21 (1.06, 1.37) With hypertension aOR 1.49 (1.00, 2.21) | Without hypertension aOR 1.11 (1.02, 1.20) With hypertension aOR 1.16 (0.96, 1.41) | Without hypertension aOR 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) With hypertension aOR 1.04 (0.94, 1.16) |

| Padula et al., 2019 [31] | NO2 | 28,788/252,205 | San Joaquin Valley, CA 2000–2006, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure in the highest quartile (17.3 ppb) combined to the lowest three quartiles combined, median 17.3 ppb | Very PTB Without diabetes aOR 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) With diabetes aOR 0.92 (0.64, 1.33) Extreme PTB Without diabetes aOR 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) With diabetes aOR 1.56 (0.87, 2.80) | Without diabetes aOR 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) With diabetes aOR 1.04 (0.79, 1.37) | Without diabetes aOR 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) With diabetes aOR 0.99 (0.87, 1.12) |

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: Very or Extreme PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Moderate PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Late PTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| He et al., 2022 [36] | PM2.5 | 287,433/ 3,723,169 | China 2010–2015, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (29 µg/m3), median 54 µg/m3 | Very PTB HR 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | HR 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) | HR 1.10 (1.08, 1.11) |

| Fang et al., 2022 [37] | PM2.5 | 1062/ 24,001 | Beijing, China 2014–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, mean 85.9 µg/m3 for first trimester, 84.9 µg/m3 for second trimester, and 82.7 µg/m3 for third trimester | Very PTB First trimester exposure aOR 0.90 (0.72, 1.13) Second trimester exposure aOR 0.98 (0.76, 1.26) Third trimester exposure aOR 3.31 (2.46, 4.46) | First trimester exposure aOR 0.97 (0.91, 1.03) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) Third trimester exposure aOR 1.90 (1.74, 2.08) | |

| Zhang et al. 2020 [44] | PM2.5 | 273/ 2101 | Wuhan City, China 2013–2015, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, mean 84.5 µg/m3 | Very PTB Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.496 (1.222, 1.778) First trimester aOR 1.265 (1.116, 1.417) Second trimester aOR 1.111 (1.005, 1.218) Third trimester aOR 1.054 (0.925, 1.186) | Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.230 (1.18, 1.344) First trimester aOR 1.170 (1.071, 1.269) Second trimester aOR 1.051 (1.008, 1.094) Third trimester aOR 1.053 (1.000, 1.106) | |

| Guo et al. 2018 [39] | PM2.5 | 35,261/ 426,246 | China 2014, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, median 57.9 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy, 57.9 µg/m3 for first trimester, 60.3 µg/m3 for second trimester, 52.3 µg/m3 for third trimester | Very PTB Entire pregnancy exposure aHR 1.12 (1.11, 1.14) First trimester exposure aHR 1.07 (1.06, 1.08) Second trimester exposure aHR 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) Third trimester exposure aHR 1.11 (1.10, 1.12) | ||

| Guo et al. 2023 [40] | PM2.5 | 237/ 10,916 | Tianjin, China, Retrospective Cohort | By exposure higher than median (75 µg/m3) during oogensis and spermatogenesis | No statistically significant association between PM2.5 exposure during both oogenesis and spermatogenesis and any preterm birth, moderate PTB, very PTB, or extreme PTB. | ||

| Qiu et al. 2023 [41] | PM2.5 | 82,820/ 2,294,188 | China 2013–2019, Retrospective Cohort | Per 10 µg/m3, mean 52.5 µg/m3 | Very PTB aOR 2.06 (1.95, 2.17) | aOR 1.28 (1.26, 1.30) | |

| Zhou, 2022 [42] | PM2.5 | 15,224/ 697,316 | Henan Province, China 2014–2016, Retrospective Cohort | Per SD (11.7–27.6 µg/m3), mean 72.3 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy, 71.1 µg/m3 for first trimester, 72.3 µg/m3 for second trimester, and 73.5 µg/m3 for third trimester | Early PTB (<34 weeks) Entire pregnancy exposure OR 1.682 (1.623, 1.744) First trimester exposure OR 0.898 (0.840, 0.961) Second trimester exposure OR 1.061 (0.988, 1.139) Third trimester exposure OR 1.353 (1.261, 1.452) | Late PTB (34–36 weeks) Entire pregnancy exposure OR 1.593 (1.559, 1.627) First trimester exposure OR 1.102 (1.060, 1.146) Second trimester exposure OR 1.217 (1.166, 1.270) Third trimester exposure OR 1.228 (1.180, 1.279) | |

| Chen, 2021 [45] | PM2.5 | 241/ 10,960 | Tianjin, China, 2014–2016, Retrospective Cohort | Per 5 µg/m3, mean 55 µg/m3 | Very PTB HR 3.52 (2.42, 5.13) Extreme PTB HR 2.11 (1.83, 2.44) | HR 2.06 (1.68, 2.52) | |

| Wang, 2018 [46] | PM2.5 | 25,879/ 469,975 | Guangzhou, China 2015–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR increase (27 µg/m3), median 34 µg/m3 | Very PTB HR 1.671 (0.423, 6.596) | HR 0.982 (0.580, 1.663) | |

| Jiang et al. 2023 [16] | PM2.5 | 1146/ 19,900 | Shanghai, China 2015–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR (9.6 µg/m3), median 49.0 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy | Early PTB (<34 weeks’ gestation Entire pregnancy exposure aOR 1.80 (1.47, 2.19) First trimester exposure aOR 1.58 (1.20, 2.08) Second trimester exposure aOR 1.64 (1.42, 1.89) Third trimester exposure aOR 3.36 (2.45, 4.64) | ||

| Studies investigating effect modification by temperature | |||||||

| Zhang et al. 2023 [38] | PM2.5 | 4257/ 196,780 | Huai River Basin, China 2013–2018, Retrospective Cohort | Exposure above Median (>77.5–95.1 µg/m3) | In extreme heat, very PTB: Second trimester OR 2.841 (1.910, 4.224) Third trimester OR 2.117 (1.367, 3.278) | In extreme heat, very PTB: First trimester OR 1.290 (1.048, 1.589) Third trimester OR 1.971 (1.631, 2.381) | |

| Study | Pollutant | Sample Size (Preterm cases/Overall n) | Setting and Study Type | Exposure Increment | Outcomes: Very or Extreme PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Moderate PTB Estimate (95% CI) | Outcomes: Late PTB Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al., 2022 [42] | NO2 | 15,224/697,317 | Henan Province, China 2014–2016, Retrospective Cohort | Per SD (8.0–12.0 µg/m3), mean 37.5 µg/m3 for entire pregnancy, 36.6 µg/m3 for first trimester, 37.6 µg/m3 for second trimester, 38.1 µg/m3 for third trimester | Early PTB (<34 weeks) Entire pregnancy exposure OR 1.682 (1.623, 1.744) First trimester exposure OR 1.754 (1.672, 1.840) Second trimester exposure OR 1.917 (1.823, 2.016) Third trimester exposure OR 1.887 (1.797, 1.982) | Entire pregnancy exposure OR 1.593 (1.559, 1.627) First trimester exposure OR 1.713 (1.665, 1.762) Second trimester exposure OR 1.784 (1.730, 1.839) Third trimester exposure OR 1.850 (1.800, 1.901) | |

| Chen et al., 2021 [45] | NO2 | 241/10,960 | Tianjin, China 2014–2016, Retrospective Cohort | Per 3 µg/m3, mean 41.6 µg/m3 | Very PTB HR 3.26 (2.06,5.14) Extreme PTB HR 1.21 (1.06,1.38) | HR 1.56 (1.25,1.94) | |

| Wang et al., 2018 [46] | NO2 | 25,879/469,975 | Guangzhou, China 2015–2017, Retrospective Cohort | Per IQR increase (29 ppb), median 42 ppb | Very PTB HR 2.805 (2.037, 3.861) | Moderate PTB HR 1.133 (0.969, 1.326) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abellard, L.; Le, V.; Nelin, T.D.; DeMauro, S.B.; Scott, K.; Clougherty, J.E.; Burris, H.H. Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review Focused on Preterm Birth Phenotype and Specific Lengths of Gestation. Children 2026, 13, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010002

Abellard L, Le V, Nelin TD, DeMauro SB, Scott K, Clougherty JE, Burris HH. Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review Focused on Preterm Birth Phenotype and Specific Lengths of Gestation. Children. 2026; 13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbellard, Lindsey, Vy Le, Timothy D. Nelin, Sara B. DeMauro, Kristan Scott, Jane E. Clougherty, and Heather H. Burris. 2026. "Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review Focused on Preterm Birth Phenotype and Specific Lengths of Gestation" Children 13, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010002

APA StyleAbellard, L., Le, V., Nelin, T. D., DeMauro, S. B., Scott, K., Clougherty, J. E., & Burris, H. H. (2026). Air Pollution and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review Focused on Preterm Birth Phenotype and Specific Lengths of Gestation. Children, 13(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010002