Do They Already Feel Like Frauds? Exploring the Impostor Phenomenon in Children and Adolescents

Highlights

- •

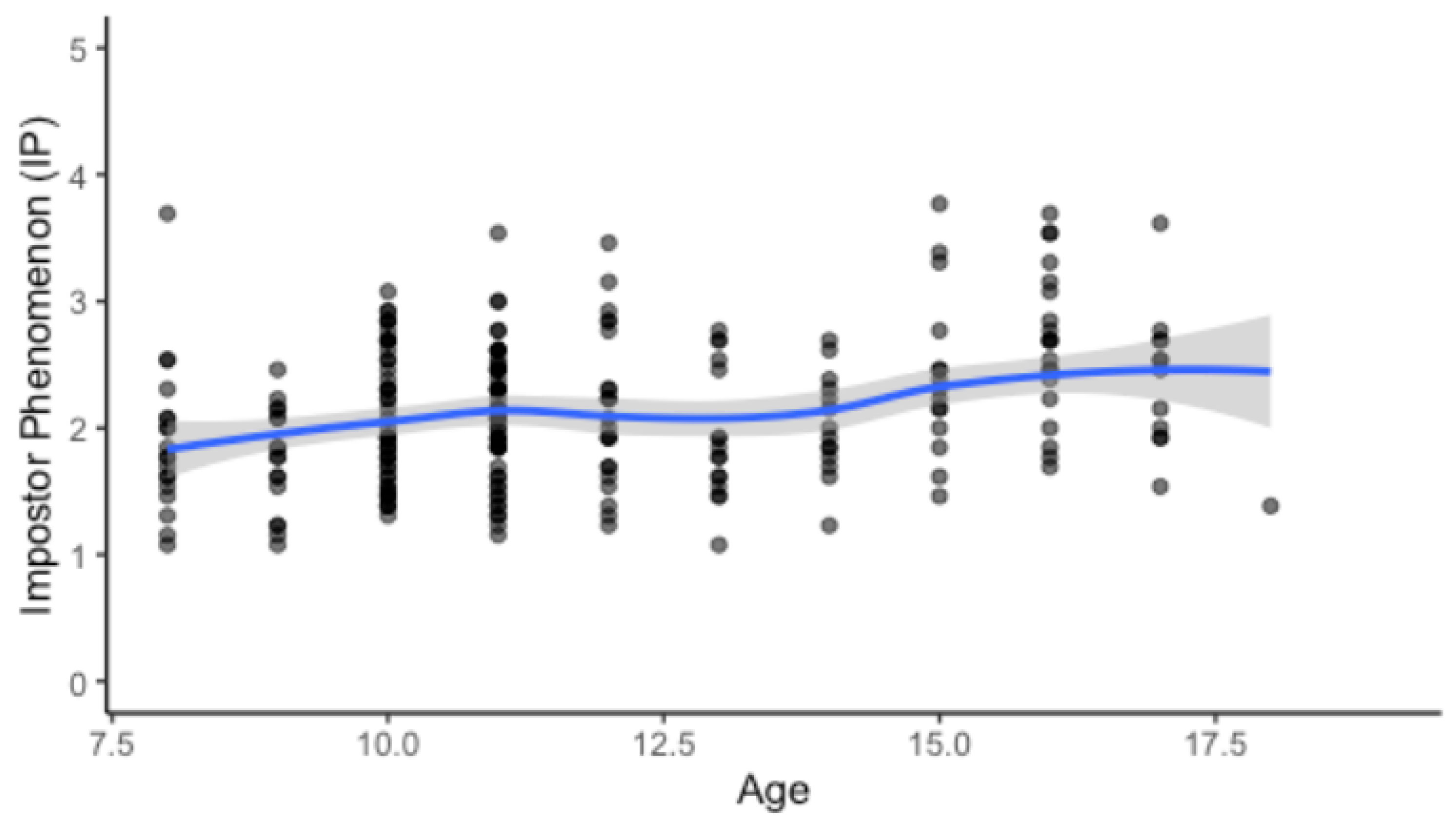

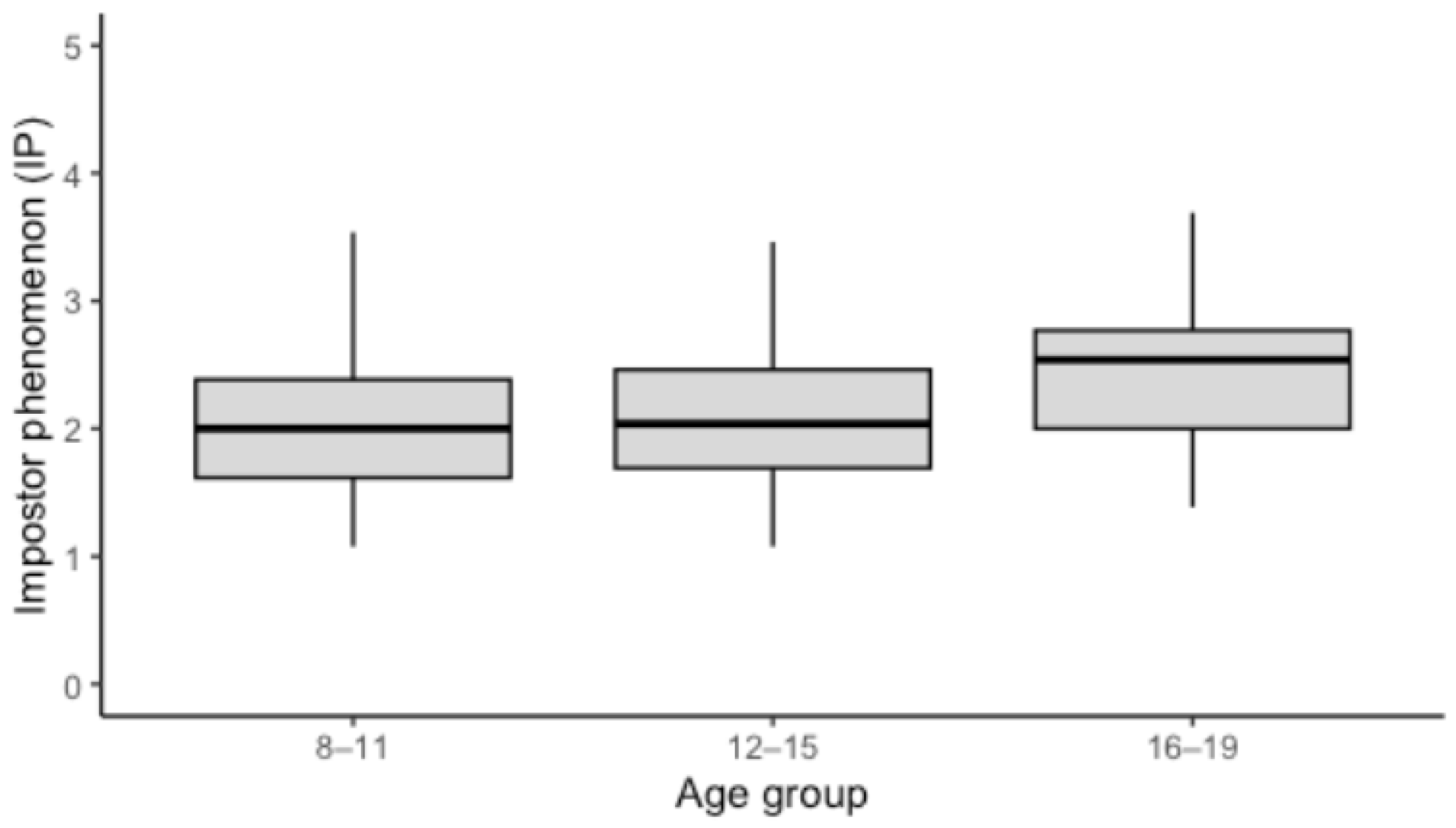

- Impostor feelings can already emerge in childhood and show a gradual increase across adolescence, indicating a developmentally sensitive trajectory rather than a phenomenon limited to adulthood.

- •

- Higher impostor scores in children and adolescents are associated with a personality profile characterized by elevated neuroticism, lower extraversion, and consciousness, as well as lower self-esteem (level, stability, and contingency).

- •

- The early emergence of impostor feelings underscores the necessity of conceptualizing impostorism as a developmentally salient, predominantly subclinical phenomenon with potential implications for mental health across the lifespan.

- •

- Preventive efforts in childhood and adolescence, particularly those fostering stable self-worth and supportive, authoritative parenting, may help mitigate the consolidation of impostor feelings and related internalizing symptoms.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prevalence of Impostor Feelings in Children and Adolescents

1.2. Personality, Self-Esteem, and Impostorism

1.3. Clinical Perspectives

1.4. Resilience Factors and Resources

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Correlations Between IP, the Big Five Personality Traits, and Self-Esteem

3.2. Clinical Sample Analyses

3.3. Personal and Social Resources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clance, P.R.; Imes, S. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1978, 15, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S. Wenn Große Leistungen zu Großen Selbstzweifeln Führen: Das Hochstapler-Selbstkonzept und Seine Auswirkungen; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chayer, M.; Bouffard, T. Relations between impostor feelings and upward and downward identification and contrast among 10- to 12-year-old students. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2010, 25, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, B.; Brown, N.; Sanchez-Huceles, J.; Adair, F.L. The impostor phenomenon and personality characteristics of high school honor students. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1990, 5, 563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, Y. Students’ recollections of parenting styles and impostor phenomenon: The mediating role of social anxiety. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, G.F.; De Santiago Campos, I.F.; Carneiro, A.G.; De Sena Silva, I.N.; De Barros Silva, P.G.; Peixoto, R.A.C.; Augusto, K.L.; Peixoto, A.A. Relationship between resilience and the impostor phenomenon among undergraduate medical students. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2022, 9, 23821205221096105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergauwe, J.; Wille, B.; Feys, M.; De Fruyt, F.; Anseel, F. Fear of being exposed: The trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, M.; Bechtoldt, M.N.; Rohrmann, S. All impostors aren’t alike—Differentiating the impostor phenomenon. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, L.N.; Gee, D.E.; Posey, K.E. I feel like a fraud and it depresses me: The relation between the impostor phenomenon and depression. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2008, 36, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S.; Bechtoldt, M.N.; Leonhardt, M. Validation of the impostor phenomenon among managers. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassl, F.; Yanagida, T.; Kollmayer, M. Impostors dare to compare: Association between the impostor phenomenon, gender typing, and social comparison orientation in university students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravata, D.M.; Watts, S.A.; Keefer, A.L.; Madhusudhan, D.K.; Taylor, K.T.; Clark, D.M.; Hagg, H.K. Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1252–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokley, K.; McClain, S.; Enciso, A.; Martinez, M. An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2013, 41, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kananifar, N.; Seghatoleslam, T.; Atashpour, S.H.; Hoseini, M.; Habil, M.H.B.; Danaee, M. The relationships between imposter phenomenon and mental health in Isfahan universities students. Intern. Med. J. 2015, 22, 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, J.H.; Piedmont, R.L.; Estadt, B.K.; Wicks, R.T. Personological evaluation of Clance’s Imposter Phenomenon Scale in a korean sample. J. Personal. Assess. 1995, 65, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, K.; Proyer, R.T. Are impostors playful? Testing the association of adult playfulness with the impostor phenomenon. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhauer, M.; Wossidlo, J.; Michael, L.; Enge, S. The impostor phenomenon: Toward a better understanding of the nomological network and gender differences. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 764030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.C.; Holcomb, B.; Payne, M.B. Gender Differences in Impostor Phenomenon: A Meta-Analytic Review. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2024, 7, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, T.; Lessing, N.; Greeve, W.; Dresbach, S. Selbstkonzept und Selbstwert. In Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters; Lohaus, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja, D.; Barbole, A.; Gowda, B.; Singh Deo, J.; Panchal, D. A cross-sectional study of the influence of perceived parenting on the levels of imposter phenomenon in young adults. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2023, 11, 2354–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, Y. Maternal and paternal authoritarian parenting and adolescents’ impostor feelings: The mediating role of parental psychological control and the moderating role of child’s gender. Children 2023, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.R.; Stewart, J.; Mugge, M.; Fultz, B. The imposter phenomenon, achievement dispositions, and the five factor model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, K.; Wolf, A. Validation of the german-language Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (GCIPS). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöstl, G.; Bergsmann, E.; Lüftenegger, M.; Schober, B.; Spiel, C. When will they blow my cover? The impostor phenomenon among Austrian doctoral students. Z. Psychol. 2012, 220, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska, A.; Gutiérrez-Doña, B.; Schwarzer, R. General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. Int. J. Psychol. 2005, 40, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clance, P.R. The Impostor Phenomenon: Overcoming the Fear that Haunts Your Success; Peachtree: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, N.; Bowker, A. Examining the impostor phenomenon in relation to self-esteem level and self-esteem instability. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, N. The Imposter Phenomenon: Insecurity Cloaked in Success; Carleton University: Ottawa, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnak, C.; Towell, T. The impostor phenomenon in British university students: Relationships between self-esteem, mental health, parental rearing style and socioeconomic status. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzak, A.; Kollmayer, M.; Schober, B. Buffering impostor feelings with kindness: The mediating role of self-compassion between gender-role orientation and the impostor phenomenon. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K.; Xia, M.; Olsen, J.A.; McNeely, C.A.; Bose, K. Feeling disrespected by parents: Refining the measurement and understanding of psychological control. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clance, P.R.; Dingman, D.; Reviere, S.L.; Stober, D.R. Impostor Phenomenon in an Interpersonal/Social Context. Women Ther. 1995, 16, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds: I. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 130, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Want, J.; Kleitman, S. Imposter phenomenon and self-handicapping: Links with parenting styles and self-confidence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, D.J. SoSci Survey (Version 3.7.06) [Computer Software]. SoSci Survey GmbH. 2025. Available online: https://www.soscisurvey.de (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Lenzner, T.; Hadler, P.; Neuert, C. Impostor-Selbstkonzept-Fragebogen für Kinder und Jugendliche (ISF-KJ). Kognitiver Pretest. GESIS Projektbericht. Version: 1.0. GESIS—Pretestlabor. 2023. Available online: https://pretest.gesis.org/pretestProjekt/Goethe-Uni-Frankfurt-a.M.-GESIS-Rohrmann-Impostor-Selbstkonzept-Fragebogen-f%C3%BCr-Kinder-und-Jugendliche-%28ISF-JK%29 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Leonhardt, M.; Hannemann, S.; Lange, K.; Rammstedt, B.; Rohrmann, S. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire for Assessing the Impostor Self-Concept in Children and Adolescents. under review.

- Kupper, K.; Rohrmann, S.; Krampen, D.; Rammstedt, B. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory für Kinder und Jugendliche; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schöne, C.; Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. Selbstwertinventar für Kinder und Jugendliche (SEKJ); Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lohaus, A.; Nussbeck, F.W. Fragebogen zu Ressourcen im Kindes- und Jugendalter; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Maas, C.J.; Hox, J.J. The influence of violations of assumptions on multilevel parameter estimates and their standard errors. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2004, 46, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Roebers, C.M. Entwicklung des Selbstkonzepts. In Handbuch der Entwicklungspsychologie; Hasselhorn, M., Schneider, W., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2007; pp. 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Lohaus, A.; Vierhaus, M.; Lemola, S. Entwicklungspsychologie des Kindes- und Jugendalters für Bachelor, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.L.; Orth, U.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Kühnel, A. Age differences in instability, contingency, and level of self-esteem across the life span. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R.W.; Trzesniewski, K.H. Self-Esteem Development Across the Lifespan. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselman, T.D.; Self, P.A.; Self, A.L. Adolescent attributes contributing to the imposter phenomenon. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenck, H.J. The Structure of Human Personality (Psychology Revivals), 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, M.; Farugie, A.; Jagoda, D.; Kaeding, A.; Rohrmann, S. Beyond gender—The impostor phenomenon and the role of gender typing, social comparison orientation, and perceived minority status. Acta Psychol. 2025, 258, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Competence and Substance Use. J. Early Adolesc. 1991, 11, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E. Annual Research Review: Cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2022, 63, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Impostor Phenomenon | 2.11 | 0.59 | |||||

| 2. Neuroticism | 3.08 | 0.89 | 0.652 *** | ||||

| 3. Extraversion | 3.31 | 1.07 | −0.428 *** | −0.412 *** | |||

| 4. Conscientiousness | 3.25 | 0.75 | −0.267 *** | −0.321 *** | 0.155 * | ||

| 5. Openness | 3.75 | 0.68 | −0.010 | 0.004 | 0.153 * | 0.272 *** | |

| 6. Agreeableness | 3.73 | 0.75 | 0.010 | −0.016 | 0.106 | 0.243 ** | 0.394 *** |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Impostor Phenomenon | 2.11 | 0.59 | |||

| 2. Self-esteem level | 3.53 | 0.96 | −0.57 *** | ||

| 3. Self-esteem stability | 3.07 | 0 | −0.611 *** | 0.515 *** | |

| 4. Self-esteem contingency | 2.94 | 0.86 | −0.656 *** | 0.511 *** | 0.578 *** |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Impostor Phenomenon | 2.11 | 0.59 | ||||||||||

| 2. Self-worth | 2.99 | 0.81 | −0.321 ** | |||||||||

| 3. Optimism | 2.78 | 0.63 | −0.30 ** | 0.730 *** | ||||||||

| 4. Self-efficacy | 2.74 | 0.63 | −0.260 * | 0.722 ** | 0.691 *** | |||||||

| 5. Empathy | 2.97 | 0.62 | 0.024 | 0.145 | 0.209 *** | 0.293 ** | ||||||

| 6. Sense of Coherence | 2.90 | 0.56 | −0.268 ** | 0.617 *** | 0.662 *** | 0.663 *** | 0.348 *** | |||||

| 7. self-control | 2.73 | 0.62 | −0.041 | 0.542 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.499 *** | 0.312 ** | 0.454 *** | ||||

| 8. Parental support | 3.45 | 0.70 | −0.243 * | 0.484 *** | 0.287 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.069 | 0.265 ** | 0.347 *** | |||

| 9. Authoritative parenting style | 3.16 | 0.69 | −0.247 * | 0.324 ** | 0.141 | 0.269 ** | 0.288 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.434 *** | 0.621 *** | ||

| 10. Integration Peer Group | 3.13 | 0.61 | −0.172 | 0.280 ** | 0.265 * | 0.280 ** | 0.215 * | 0.336 *** | 0.281 ** | 0.385 *** | 0.429 *** | |

| 11. Integration School | 2.83 | 0.69 | −0.204 | 0.478 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.380 *** | 0.209 * | 0.330 ** | 0.502 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.585 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leonhardt, M.; Vries, J.D.; Etzler, S.; Peetz, S.; Rohrmann, S. Do They Already Feel Like Frauds? Exploring the Impostor Phenomenon in Children and Adolescents. Children 2026, 13, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010149

Leonhardt M, Vries JD, Etzler S, Peetz S, Rohrmann S. Do They Already Feel Like Frauds? Exploring the Impostor Phenomenon in Children and Adolescents. Children. 2026; 13(1):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonhardt, Mona, Jane De Vries, Sonja Etzler, Sarah Peetz, and Sonja Rohrmann. 2026. "Do They Already Feel Like Frauds? Exploring the Impostor Phenomenon in Children and Adolescents" Children 13, no. 1: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010149

APA StyleLeonhardt, M., Vries, J. D., Etzler, S., Peetz, S., & Rohrmann, S. (2026). Do They Already Feel Like Frauds? Exploring the Impostor Phenomenon in Children and Adolescents. Children, 13(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010149