1. Introduction

According to the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS), nocturnal enuresis (NE) is defined as involuntary, intermittent bedwetting during sleep in children aged 5 years or older and is more common in males. The prevalence exceeds 10% at 6 years of age, decreases to approximately 5% at 10 years, and falls to 0.5–1% in adolescents and young adults [

1,

2]. Although the underlying pathophysiology is not fully understood, NE is considered a multifactorial condition resulting from the interaction of maturational delay, genetic predisposition, nocturnal polyuria, disturbed sleep, reduced bladder capacity, and detrusor overactivity [

3]. Spontaneous resolution occurs in about 15% of affected children annually. NE is classified as primary when no sustained dry period of at least six months has ever been achieved, and secondary when bedwetting recurs after a dry period of six months or longer.

Primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE) is a common pediatric condition characterized by nighttime bedwetting in the absence of daytime lower urinary tract symptoms and is influenced by mechanisms such as nocturnal polyuria, reduced functional bladder capacity (FBC), and impaired arousal [

1]. First-line management of PMNE includes education and counseling regarding the condition. In patients who do not benefit from initial approaches, alarm therapy, behavioral interventions, and pharmacological treatments become prominent options [

2,

3]. Current recommendations suggest that PMNE associated with nocturnal polyuria should be treated primarily with desmopressin, whereas PMNE characterized by reduced bladder capacity should be managed with alarm therapy as the first-line intervention. Anticholinergic agents such as oxybutynin are not theoretically indicated for routine PMNE treatment and should be considered only in a very small subgroup of patients with nocturnal overactive bladder during sleep [

2].

Although alarm therapy, desmopressin, and combination treatments yield favorable short-term results, long-term relapse after discontinuation remains a major clinical challenge, with relapse rates varying widely across studies [

4,

5]. While factors such as age, baseline wet-night frequency, and bladder capacity have been identified as predictors of treatment response, the prognostic value of FBC remains inconsistent, largely due to methodological differences in bladder capacity assessment [

6]. Functional bladder capacity may be reduced by up to 50% in children with nocturnal enuresis, with low age-adjusted FBC reported in 46.5% of patients and more commonly observed in those with daytime wetting and frequent nocturnal enuresis episodes [

7]. Notably, many previous studies analyzed MNE and NMNE together, although reduced bladder capacity is an expected characteristic of NMNE due to the presence of underlying daytime lower urinary tract dysfunction, which may have confounded earlier findings [

4,

6]. In particular, the relationship between FBC measured by a 48 h voiding chart and FBC obtained via uroflowmetry (UFM) in predicting long-term relapse has not been clearly defined.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine one-year relapse rates among children with PMNE who achieved complete remission after treatment and to identify relapse predictors, with a specific focus on comparing bladder capacity measurements derived from voiding diaries and UFM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Group

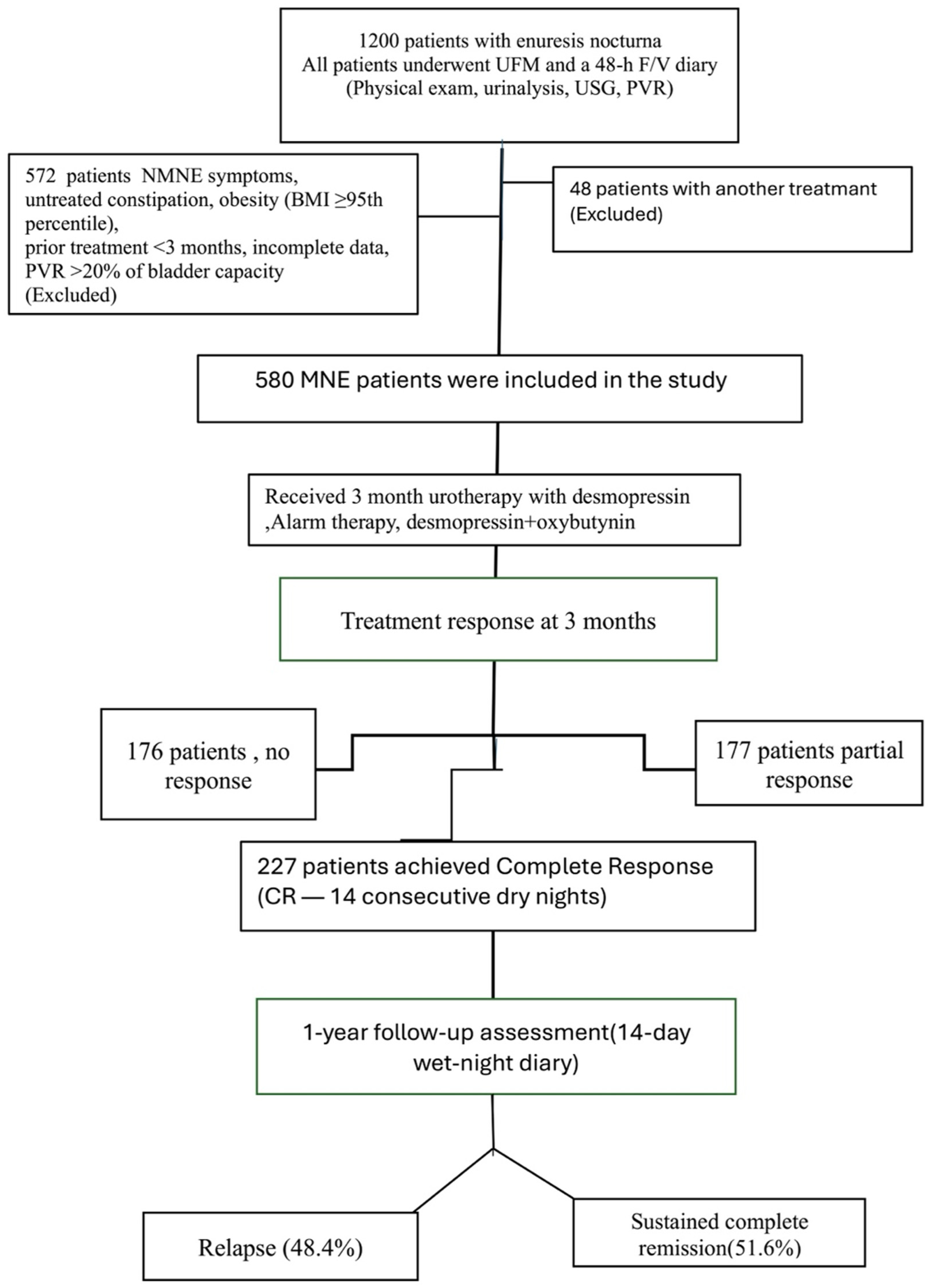

The data in this study, including 227 patients, were obtained retrospectively from the data processing system of the Pediatric Urology and Pediatrics Clinics of Ümraniye Training and Research Hospital between January 2022 and May 2024. In our clinic, all children presenting with nocturnal enuresis undergo a standardized evaluation that includes a 48 h frequency/volume (48 h F/V) charts, uroflowmetry (UFM), and urinary tract ultrasonography. According to the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) definitions, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (MNE) is characterized by nighttime bedwetting in children aged ≥5 years without any daytime lower urinary tract symptoms. Accordingly, none of the included children exhibited urgency, frequency, daytime incontinence, voiding postponement, infrequent voiding, dysuria, or weak urinary stream. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 5 years, a confirmed diagnosis of PMNE, availability of complete (48 h F/V) charts and UFM data, documented post-void residual urine volume (PVR) assessment, receipt of alarm therapy, desmopressin, or combination treatment, and achievement of complete remission after a 3-month treatment course. Children with daytime lower urinary tract symptoms (NMNE), recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary or neurological disorders, untreated constipation, obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), prior enuresis treatment within the preceding 3 months, incomplete data, protocol non-adherence, or a post-void residual exceeding 20% of functional bladder capacity were excluded from the study (

Figure 1).

All children were evaluated in accordance with ICCS guidelines, including physical examination, urinalysis, urinary ultrasonography, a 48 h F/V charts, UFM, and post-void residual (PVR) assessment [

8]. Seven-day nocturnal wetting records were completed both before and after treatment. Patients who achieved complete remission after three months of treatment were invited for a follow-up evaluation one year later, during which 7-day nocturnal wetting records were obtained again. All children underwent uroflowmetry and completed 48 h frequency/volume (48 h F/V) charts prior to treatment.

In accordance with ICCS recommendations, 48 h frequency/volume charts were used to assess bladder capacity, recording the timing and volume of each void as well as total fluid intake [

8]. Voiding diaries were required to be completed for at least two consecutive days, and the maximum voided volume—excluding the first morning void—was included in the analysis, as the first morning void generally reflects overnight urine production [

8].

At the initial visit, parents were thoroughly instructed by the physician on how to perform voiding measurements. All recordings were carried out during weekends under parental supervision. This approach was chosen because all enrolled children were of school age, and weekday recordings could be compromised by school attendance and parental work schedules. The rationale for this procedure was explained in detail to parents or caregivers during the clinical visit [

8].

Bladder capacity was assessed using both the maximum voided volume derived from 48 h F/V charts and UFM-based measurements. Uroflowmetry was repeated when initial tracings were suboptimal, and abnormal flow patterns (tower, staccato, intermittent, or plateau) were excluded. Post-void residual urine (PVR) was interpreted according to age; incomplete bladder emptying may be physiological in infants and young children, whereas older children are expected to empty the bladder completely. A PVR volume greater than 20 mL was considered suggestive of abnormal or incomplete bladder emptying [

1]. Maximum bladder capacity was calculated as the largest voided volume plus PVR [

9]. Expected bladder capacity (EBC) was calculated using the ICCS formula (age × 30) + 30 mL [

9], and capacities were classified as low (<65% EBC), normal (65–150%), or high (>150%), with distributions reported separately for chart-based and UFM-based measurements [

8].

2.2. Treatment

All patients received standard urotherapy, which included regular daytime voiding, regulation of bowel habits, voiding before bedtime, and restriction of evening fluid intake. Families were thoroughly instructed on the use of alarm therapy, including the steps required to assist the child in awakening during the initial weeks of treatment. Patients were monitored every two weeks during the first month and subsequently once monthly up to the end of the third month. At each visit, a pediatric urologist evaluated both the child and the caregivers, provided reinforcement of urotherapy instructions, and contacted families by telephone if follow-up appointments were missed.

Pharmacologic treatment consisted of fast-release oral desmopressin. The initial dose was 120 µg, which was increased to 240 µg in non-responders, and gradually tapered during discontinuation. Combination therapy (desmopressin plus oxybutynin) was initiated in children who had previously used desmopressin without adequate response and who had been off all treatments for at least three months. Oxybutynin was administered at 0.2–0.4 mg/kg/day (maximum 0.4 mg/kg/day) for a total of three months and was tapered by alternate-day reductions during the discontinuation phase, while desmopressin therapy was continued concurrently.

Patients were categorized into three treatment groups: alarm (n = 24), desmopressin (n = 121), and desmopressin plus oxybutynin (n = 82). At the end of the 3-month treatment period, medications were discontinued using a structured tapering protocol (alternate-day dosing over a two-week period). Complete remission was defined as 14 consecutive dry nights, and treatment was stopped once this criterion was achieved. Treatment response was classified according to ICCS criteria: no response (NR), <50% reduction in wet nights; partial response (PR), 50–99% reduction; and complete response (CR), 100% reduction (full dryness).

Children who had achieved complete remission were instructed to return for evaluation if any symptoms recurred after structured discontinuation of therapy. However, those who did not present for follow-up during this period (

n = 227) were contacted by telephone one year later and invited to the clinic for reassessment. None of these children had received any additional medication or sought care at another clinic during the interval. At this follow-up visit, patients were re-evaluated using a 14-day wet-night diary. Relapse was defined as the occurrence of more than one wet night per month after complete remission had been achieved [

8]. Clinical and demographic characteristics were compared between children with and without relapse. Potential predictors of relapse included sex, age, family history, treatment modality, pre-treatment bladder capacity (48 h F/V charts and UFM-based), and pre- and post-treatment wet-night frequency.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess normality of the data distribution. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, frequency, and proportion) were reported. For within-group comparisons of non-parametric data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. Categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test and the Fisher–Freeman–Halton test, as appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was also used to evaluate the discriminative ability of diary-based and UFM-derived bladder capacity parameters in predicting relapse. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The mean age of the 227 patients (148 male, 79 female) was 9.12 ± 2.39 years (range: 5–18). The mean number of wet nights per week decreased significantly from 5.58 ± 0.78 before treatment to 2.1 ± 2.5 at the one-year follow-up (

p < 0.001). Desmopressin monotherapy was administered to 53.3% of patients, desmopressin plus oxybutynin to 36.1%, and alarm therapy to 10.6% (

Table 1).

The mean expected bladder capacity (EBC) was 298.5 ± 60.9 mL. Mean functional bladder capacity (FBC) measured using the 48 h F/V charts and UFM were 201.5 ± 105.4 mL and 168.9 ± 111.2 mL, respectively. 48 h F/V charts-based FBC values were significantly higher than UFM-based measurements (mean difference: 32.6 ± 110.9 mL;

p < 0.001) (

Table 2). The mean FBC in UFM/EBC ratio was decreased in 65.1%, normal in 31.7%, and increased in 3% of patients. According to the F/V chart, these proportions were 48.8% decreased, 51.1% normal (

p < 0.001). Prior to treatment, 92% of all patients had severe nocturnal enuresis (>5 wet nights/week) [

10]; however, baseline wet-night frequency was not associated with long-term treatment resistance (

p = 0.368). One year after treatment, approximately 20% of patients still exhibited severe enuresis (

Table 1).

A total of 48.5% of patients experienced relapse at the one-year follow-up. A comparative analysis of relapse and non-relapse groups showed no significant differences in age, sex, family history, treatment modality (alarm, desmopressin, or combination therapy), or baseline wet-night frequency (

p > 0.05) (

Table 3).

There were no significant differences among the between groups regarding decreased, normal, or increased FBC based on the mean UFM/EBC ratio (p = 0.052).

In contrast, the voiding diary-based bladder capacity (mean FBC/EBC ratio) demonstrated a strong association with relapse, with decreased FBC significantly more common in the relapse group compared with the non-relapse group (60.9% vs. 35.9%,

p < 0.001) (

Table 3).

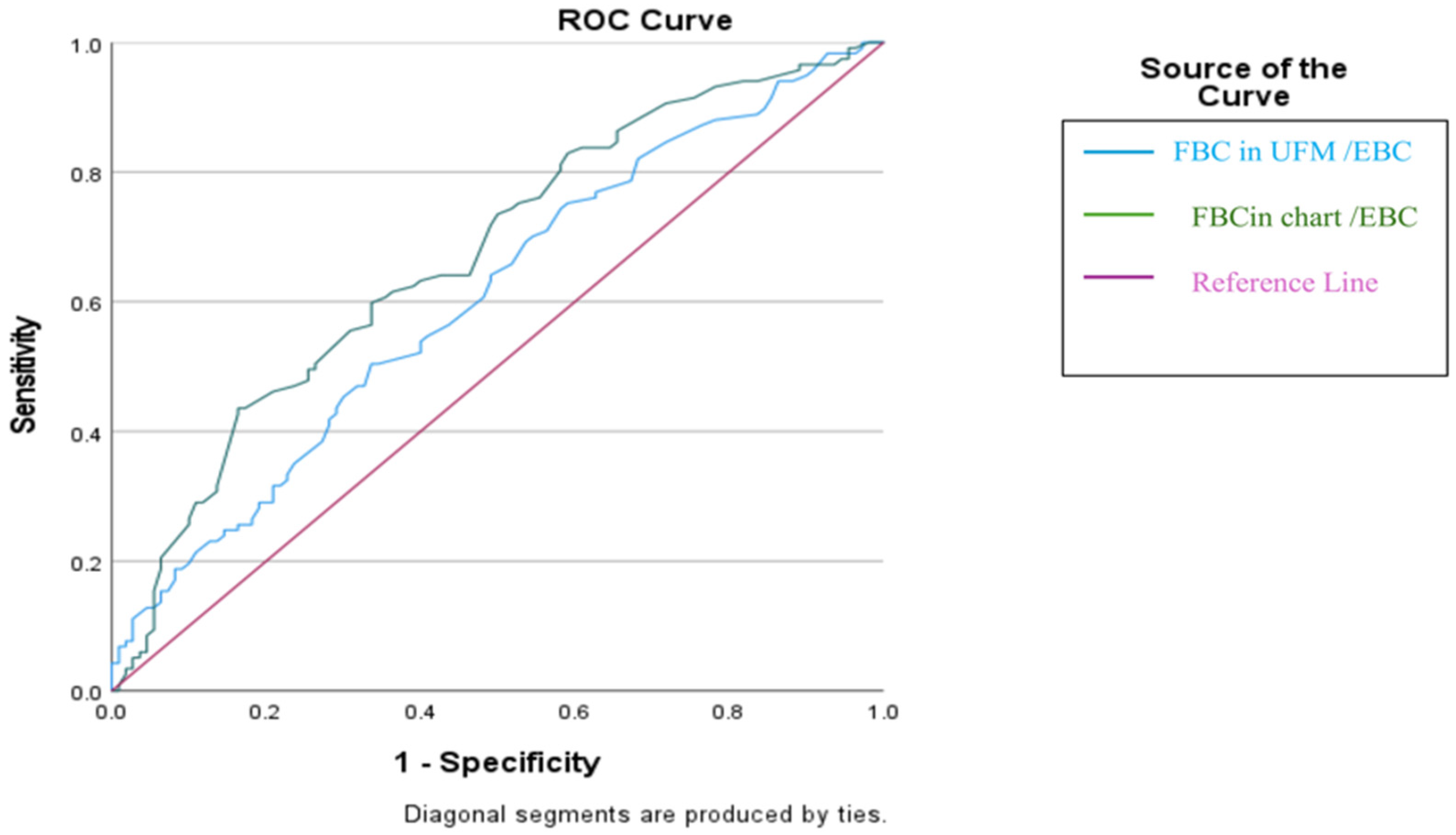

ROC analysis showed that the diary-based the mean FBC/EBC ratio had a moderate ability to identify children who would remain relapse-free, with an AUC of 0.671 (95% CI: 0.605–0.731, p < 0.0001). Using the optimal cut-off value (>79%), the model achieved 42.7% sensitivity and 83.6% specificity, indicating that values above this threshold were more reliable for predicting sustained remission (PPV for no relapse: 73.5%).

Similarly, the UFM-derived mean FBC/EBC ratio demonstrated a lower performance in predicting no relapse, with an AUC of 0.606 (95% CI: 0.539–0.670,

p = 0.0047). The >51% cut-off yielded 47.0% sensitivity and 67.3% specificity, suggesting a considerably weaker ability to identify children who would maintain remission compared with the diary-based measure (

Table 4 and

Figure 2).

In a stratified analysis of patients with complete remission, a diary-based FBC/EBC ratio >79% was consistently associated with a significantly lower risk of relapse across all treatment modalities, with a pooled Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio of 0.30 (95% CI: 0.16–0.55) and no evidence of heterogeneity between groups (

p = 0.369) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

This retrospective cohort study evaluated clinical and bladder-capacity-related predictors of long-term relapse in children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE) who initially achieved complete response to treatment. The principal finding of this study is that functional bladder capacity (FBC) measured using the 48 h frequency/volume (F/V) diary was the strongest predictor of relapse one year after treatment discontinuation, whereas FBC derived from uroflowmetry (UFM) showed no meaningful predictive value. This distinction is clinically relevant, as relapse remains one of the major challenges in the long-term management of nocturnal enuresis despite the favorable short-term outcomes associated with alarm therapy, desmopressin, and combination regimens [

2,

9,

10,

11].

The diary-based mean FBC/EBC ratio showed a moderate but statistically significant ability to predict sustained long-term remission (AUC: 0.671; 95% CI: 0.605–0.731; p < 0.0001). Notably, the optimal cut-off value of >79% yielded high specificity (83.6%) and a positive predictive value of 73.5%, indicating that children above this threshold were substantially more likely to remain relapse-free. Although the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) defines reduced bladder capacity for diagnostic purposes as an FBC/EBC ratio < 65%, the diary-based mean FBC/EBC threshold of >79% identified in our study should be interpreted as a prognostic marker rather than a diagnostic criterion. This threshold primarily serves to identify children with PMNE who are at low risk of long-term relapse, rather than to exclude relapse risk.

While the diary-based FBC/EBC ratio demonstrated modest sensitivity, its high specificity indicates that this marker is particularly useful for confidently identifying children who are likely to remain relapse-free, rather than for capturing all children at risk of relapse. This supports its role in risk stratification and individualized follow-up planning.

Previous studies have reported an association between reduced FBC and treatment resistance, particularly in relation to poor response to desmopressin and increased need for anticholinergic therapy [

2,

12,

13]. Our findings expand upon this concept by demonstrating that, even among children who initially respond to treatment, those with smaller diary-based bladder capacity are at substantially higher risk of losing remission over time. This suggests that FBC measured from voiding diaries is not only a marker of initial treatment response but also a valuable prognostic indicator of long-term outcomes.

A major limitation of much of the existing literature is the inclusion of mixed cohorts containing both MNE and NMNE. Because reduced FBC is an expected characteristic of NMNE due to underlying lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), such heterogeneity obscures the true predictive role of bladder capacity [

14]. In contrast, the present study focused exclusively on a strictly defined PMNE cohort with normal UFM patterns, normal PVR, and absence of daytime LUTS, thereby minimizing LUTD-related confounding and enabling a more accurate assessment of bladder capacity in the context of PMNE.

Another important observation was that diary-based FBC was significantly higher than UFM-based FBC (

p < 0.001). This discrepancy has been noted previously and may reflect suboptimal bladder filling, rapid pre-test hydration, or voiding anxiety during hospital-based UFM assessment [

15]. In contrast, the 48 h F/V diary captures habitual voiding patterns in a natural home environment and may therefore better represent true physiological bladder capacity. This likely explains why only diary-derived FBC, and not UFM-derived FBC, demonstrated a significant relationship with long-term outcomes.

Consistent with this observation, the UFM-derived FBC/EBC ratio showed weaker predictive performance (AUC: 0.606), with limited sensitivity and specificity, supporting the view that UFM should not be used as a standalone tool for long-term risk stratification but rather interpreted alongside diary-based assessments.

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, family history, and baseline wet-night frequency, were not associated with relapse—consistent with prior large-scale cohorts Likewise, treatment modality (alarm therapy, desmopressin, or combination therapy) did not influence long-term outcomes once complete response was achieved. These observations underscore that baseline bladder capacity, rather than therapeutic modality or demographic factors, plays the pivotal role in determining relapse risk.

Although treatment allocation was not randomized, a stratified analysis limited to patients who achieved complete remission showed that the predictive value of a diary-based mean FBC/EBC ratio > 79% was consistent across alarm, desmopressin, and combination therapy groups, supporting its robustness as a treatment-independent prognostic marker.

The relatively high number of wet nights at baseline among children in our cohort, along with the persistence of two to three wet nights per week in 61% of relapsing cases at follow-up, may reflect the tertiary-care referral nature of our center and the increased severity of cases we encounter. Studies by Borg et al. provide additional context, demonstrating that many children exhibit markedly reduced nocturnal bladder capacity despite normal daytime Maximal voided volume (MVV), which may explain desmopressin failure even in the presence of adequate antidiuretic response [

16]. Other investigations have also highlighted reduced FBC and increased bladder wall thickness on ultrasonography as potential modifiers of treatment response, particularly in relation to anticholinergic therapy [

17,

18,

19].

Due to the retrospective design of our study, the exact timing of relapse could not be determined. van Kampen et al. reported that, following comprehensive treatment, overactive bladder was the only factor significantly associated with relapse in children with primary nocturnal enuresis and emphasized that frequent clinician–family contact may independently contribute to long-term treatment effectiveness. These findings suggest that both underlying bladder dysfunction and continuity of care should be considered when interpreting long-term outcomes [

20].