Social Media Engagement and Usage Patterns, Mental Health Comorbidities, and Empathic Measures in an Italian Adolescent Sample: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaires

- -

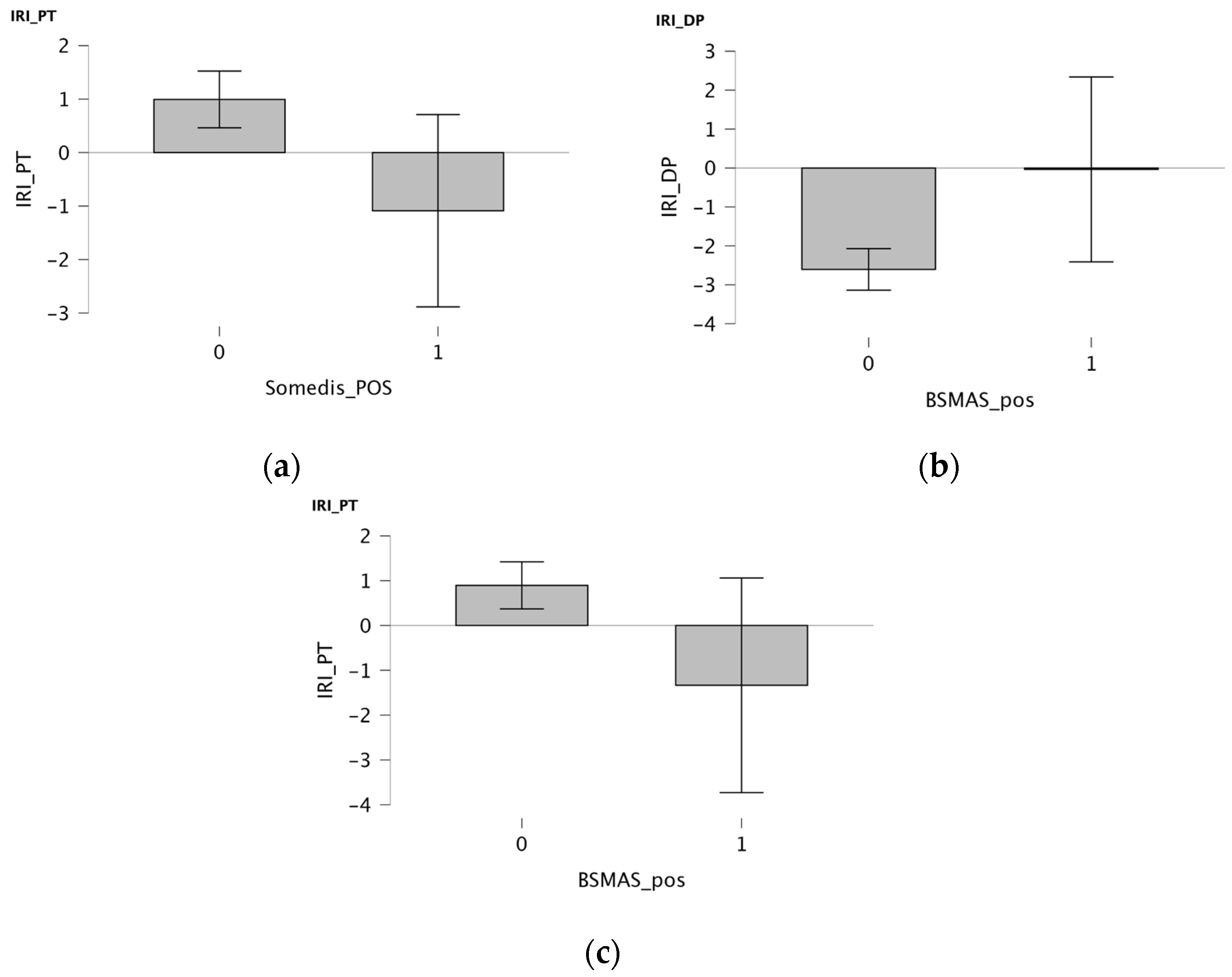

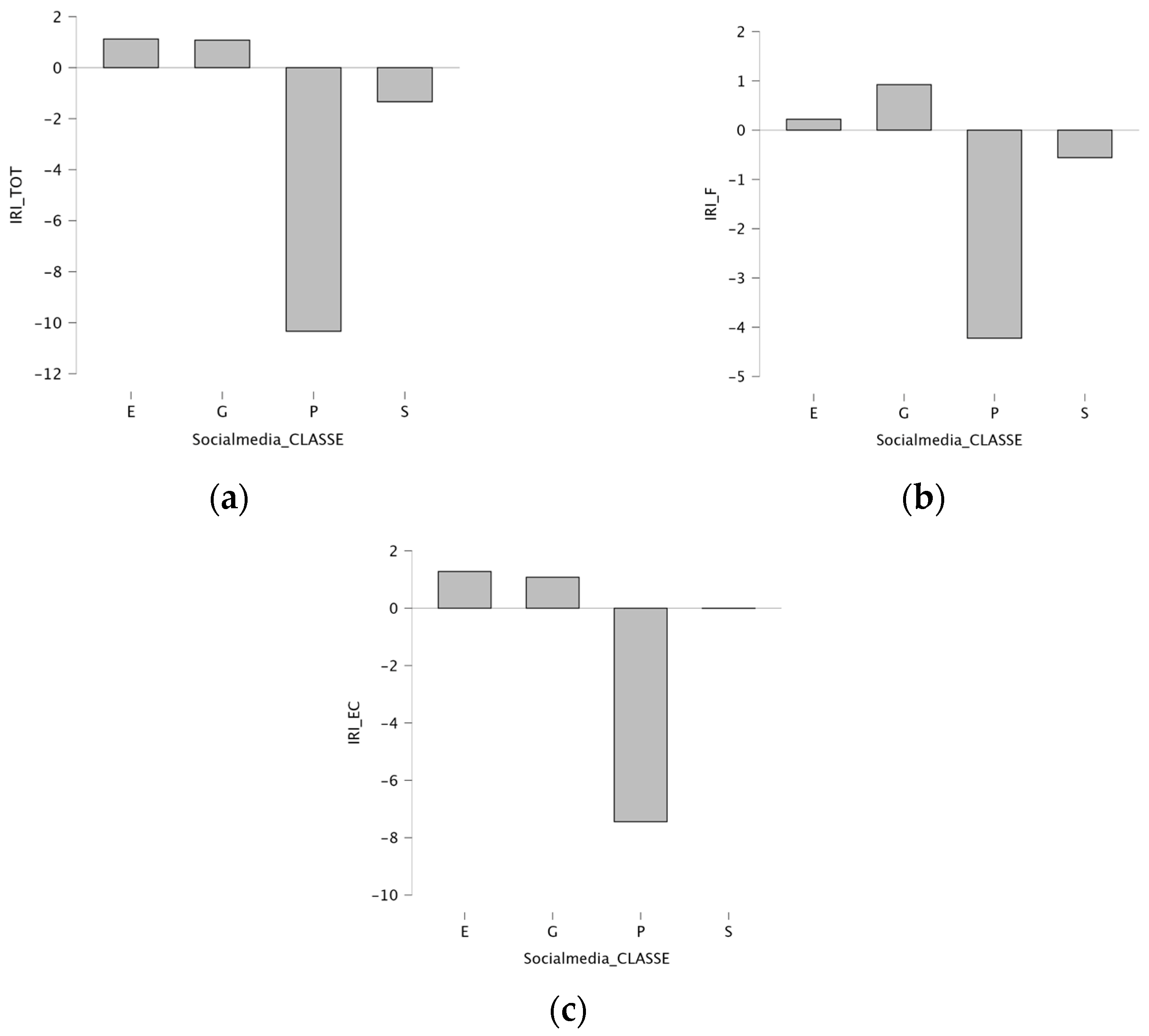

- IRI (Interpersonal Reactivity Index [37,38]), a self-report questionnaire that, in its Italian-translated and standardized version, investigates empathic abilities through 28 items and 4 subscales: perspective taking (PT) and fantasy (F) contribute to the cognitive empathy domain (EC); empathic concern (CE) and personal distress (PD) contribute to the affective empathy domain (AE). A total score can be obtained as representative of general empathic abilities of the subject. Scores range from −14 to +14 though no cut-off score was set. The IRI Italian version shows good reliability and validity in the Italian cultural context [34].

- -

- RME (Reading the Mind in the Eyes [10,39,40]) consists of 28 pictures in the ocular facial region of women and men, each accompanied by four words related to a mental or emotional state; the child is asked to choose the one that best represents what the person in the picture is feeling. It is considered an advanced Theory of Mind test where the greatest score represents higher social ability in making inferences regarding others’ mental and emotional states; it is currently available in Italy with good reliability and validity in the Italian cultural context in both its adult and child versions (the latter is the version used in the study) [39].

- -

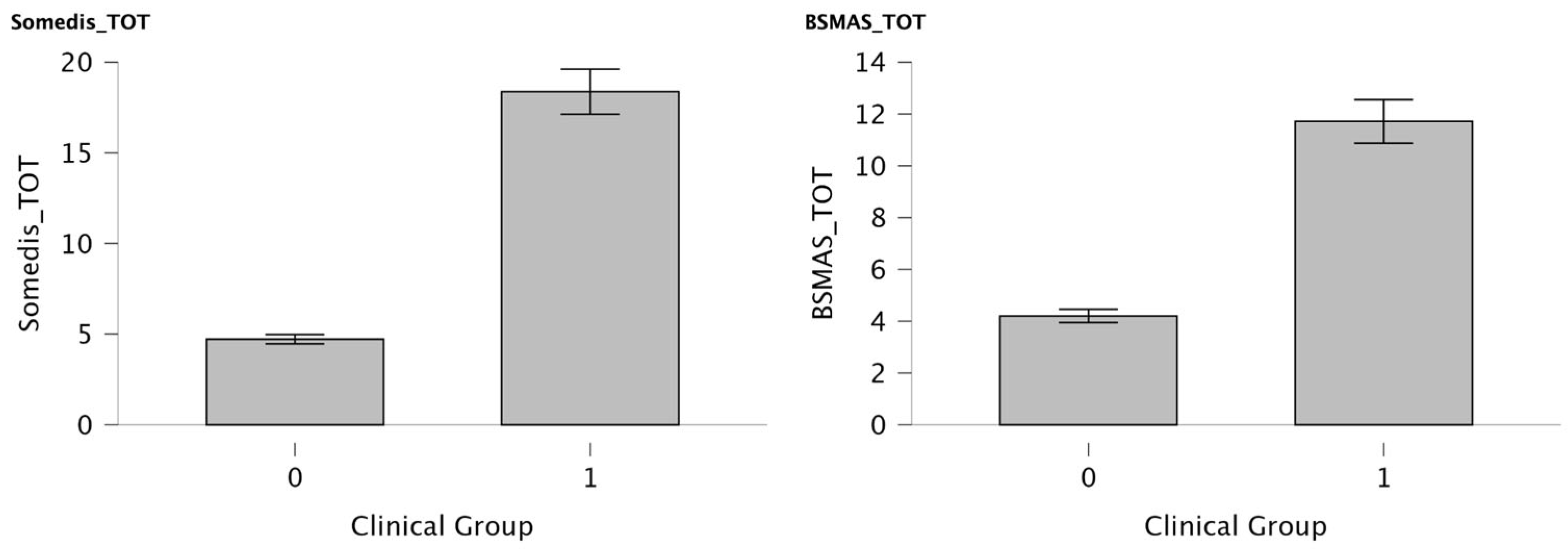

- SOMEDIS (The Social Media Use Disorder Scale for Adolescents [41]), a self-report questionnaire to assess social media problematic use based on ICD-11 and DSM-5 criteria for gaming disorders. It consists of 10 questions (9 to evaluate SM usage patterns and an extra question to assess frequency and duration of problems). The Italian validation of this questionnaire was conducted by the Italian National Institute of Health [42]. A higher total score (specifically > 20) indicates an increased risk for problematic social media use.

- -

- BSMAS (Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale [43]), a self-report questionnaire which contains six items reflecting core addiction elements (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse). In the Italian version, no clinical cut-off figure was officially established at compilation time [44], so the total score of 24 was considered clinical according to the latest national and international methodologies [45].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Subgroup Analyses

3.2. Social Media Use and Empathic Measures

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SM | Social Media |

| SOMEDIS | Social Media Disorder Scale |

| BSMAS | Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale |

| IRI | Interpersonal Reactivity Index |

| RME | Reading the Mind in the Eyes |

| PSMU | Problematic Social Media Use |

| AE | Affective Empathy |

| CE | Cognitive Empathy |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—5th Edition |

| K-SADS-PL | Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children—Present and Lifetime version |

| TQI | Total Intelligence Quotient |

| GAI | General Ability Index |

| WISC IV | Weschler Intelligent Scale for Children—IV Edition |

| WAIS IV | Weschler Adult Intelligent Scale—IV Edition |

| PT | Perspective Taking |

| F | Fantasy |

| CE | Empathic Concern |

| PD | Personal Distress |

| CGI-S | Clinical Global Impression-Severity Score |

| CGAS | Children Global Assessment Scales |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Check List |

| YSR | Youth Self Report |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| OCD | Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

| VCI | Verbal Comprehension Index |

| SMA | Social Media Addiction |

References

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment. «Social Media». Cambridge Dictionary. 2025. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/social-media (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tullett-Prado, D.; Stavropoulos, V.; Gomez, R.; Doley, J. Social media use and abuse: Different profiles of users and their associations with addictive behaviours. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2023, 17, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Social Media & User-Generated Content. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks/#section-usage (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Cheng, C.; Lau, Y.; Chan, L.; Luk, J.W. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. Unhealthy influencers? Social media and youth mental health. Lancet 2024, 404, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021, 114, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A. Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motiv. Emot. 1990, 14, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J.R. Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious. Cogn. 2005, 14, 698–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, A.; Esteves, F. Empathy development from adolescence to adulthood and its consistency across targets. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 936053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüne, M.; Brüne-Cohrs, U. Theory of mind—Evolution, ontogeny, brain mechanisms and psychopathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, L.M.; Spradlin, A.; Bunce, J.P.; Rosen, L.D. Virtual empathy: Positive and negative impacts of going online upon empathy in young adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Cheever, N.A.; Carrier, M.L. iDisorder: Understanding Our Obsession with Technology and Overcoming Its Hold on Us; Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-22141-000 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Sharma, N.; Gupta, S.; Seth, S. Impact of social media on the trait of empathy. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 8, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojak, A.K.; Bapu, V. Social Media Addiction and Empathy among Emerging Adults. Indian J. Ment. Health 2021, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihayati, H.E.; Ramadhania, A.D.L.; Nimah, L. Relationship of social media addiction with social interactions and feeling of empathy in nursing students. J. Ment. Health 2025, 1, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, S.; Altan, S. Decoding Adolescents’ Internet Addiction, Academic Achievement, and Empathy Levels: Untangling Complex Associations. In Advances in Social Networking and Online Communities; Touloupis, T., Sofos, A., Loisos Vasiou, A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursoniu, S.; Bredicean, A.-C.; Serban, C.L.; Rivis, I.; Bucur, A.; Papava, I.; Giurgi-Oncu, C. The interconnection between social media addiction, alexithymia and empathy in medical students. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1467246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiron, M. Internet and Social Media Age: What Is the Difference in Empathy Across Generations of Therapists in the UK? Doctoral Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.-S.A.; Hain, S.; Cabrera, J.; Rodarte, A. Social Media Use and Empathy: A Mini Meta-Analysis. Soc. Netw. 2019, 8, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong-Opoku, N.; Agyapong-Opoku, F.; Greenshaw, A.J. Effects of Social Media Use on Youth and Adolescent Mental Health: A Scoping Review of Reviews. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y. The Effect of Social Media on Mental Health among Adolescent. Interdiscip. Humanit. Commun. Stud. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccerillo, L.; Digennaro, S. Adolescent Social Media Use and Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2025, 10, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.M.; Alubied, A.A.; Khalaf, A.M.; Rifaey, A.A. The Impact of Social Media on the Mental Health of Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e42990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwijayanti, A.; Pratiwi, M.M.S. Social Media Addiction and Mental Health Among College Students. Philanthr. J. Psychol. 2025, 9, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zeng, X.; Su, J.; Zhang, X. The dark side of empathy: Meta-analysis evidence of the relationship between empathy and depression. PsyCh J. 2021, 10, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev, I.; Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Montag, C.; Assaf, M.; Smith, M.J.; Eran, A.; Uzefovsky, F. Empathic disequilibrium in schizophrenia: An individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 181, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Wang, Y.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Lui, S.S.Y.; Yu, X.; Madsen, K.H.; Ma, Y.; et al. Altered empathy-related resting-state functional connectivity in patients with bipolar disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 272, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Longobardi, C.; Fabris, M.A.; Settanni, M. Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 82, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, C.L.; Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Kvalem, I.L.; Wennersberg, A.-L.; Wisting, L. Further evidence of the association between social media use, eating disorder pathology and appearance ideals and pressure: A cross-sectional study in Norwegian adolescents. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spínola, L.G.; Calaboiça, C.; Carvalho, I.P. The use of social networking sites and its association with non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 16, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.J.; McGettrick, C.R.; Dick, O.G.; Ali, M.; Teeters, J.B. Time Spent on Social Media and Associations with Mental Health in Young Adults: Examining TikTok, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Youtube, Snapchat, and Reddit. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.; Rao, U.; Flynn, C.; Moreci, P.; Williamson, D.; Ryan, N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W. Structure of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition among a national sample of referred students. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, N.; Hulac, D.M.; Kranzler, J.H. Independent examination of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV): What does the WAIS-IV measure? Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Meas. Individ. Differ. Empathy Evid. Multidimens. Approach 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, P.; Ingoglia, S.; Lo Coco, A. Contributo all’adattamento italiano dell’Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Test. Psicometria Metodol. 2006, 13, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Vellante, M.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Melis, M.; Marrone, M.; Petretto, D.R.; Masala, C.; Preti, A. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test: Systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cognit. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 18, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Spong, A.; Scahill, V.; Lawson, J. Are intuitive physics and intuitive psychology independent? A test with children with Asperger Syndrome. J. Dev. Learn. Disord. 2001, 5, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Paschke, K.; Austermann, M.I.; Thomasius, R. ICD-11-Based Assessment of Social Media Use Disorder in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the Social Media Use Disorder Scale for Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 661483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortali, C.; Mastrobattista, L.; Palmi, I.; Solimini, R.; Pacifici, R.; Pichini, S.; Minutillo, A. Rapporto Istisan: Dipendenze Comportamentali Nella Generazione Z: Uno Studio di Prevalenza Nella Popolazione Scolas-tica (11–17 anni) e Focus SULLE Competenze Genitoriali. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. 21–23 December. Available online: https://www.sipad.network/dipendenze-comportamentali-nella-generazione-z-e-online-il-rapporto-istisan/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monacis, L.; De Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Qin, L.; Cheng, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Hu, M.; Tong, J.; et al. Determination the cut-off point for the Bergen social media addiction (BSMAS): Diagnostic contribution of the six criteria of the components model of addiction for social media disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C.; Rousidis, D. Social Media Types: Introducing a data driven taxonomy. Computing 2020, 102, 295–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, P.; Mendolia, S.; Yerokhin, O. Social media use and emotional and behavioural outcomes in adolescence: Evidence from British longitudinal data. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2021, 41, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psichopharmacology, Revised; Rockville, M.D., Ed.; US Department of Health, Education and Welfare: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D.; Spitzer, R.L. Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1985, 21, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-Informant Assessment; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.; Griffiths, M. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; King, N.; Walsh, S.D.; Boer, M.; Donnelly, P.D.; Harel-Fisch, Y.; Malinowska-Cieślik, M.; Gaspar De Matos, M.; Cosma, A.; et al. Social Media Use and Cyber-Bullying: A Cross-National Analysis of Young People in 42 Countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniel-Nissim, M.; Marino, C.; Galeotti, T.; Blinka, L.; Ozoliņa, K.; Craig, W.; Lahti, H.; Wong, S.L.; Brown, J.; Wilson, M. A Focus on Adolescent Social Media Use and Gaming in Europe, Central Asia and Canada: Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children International Report from the 2021/2022 Survey. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/378982 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Politte-Corn, M.; Nick, E.A.; Kujawa, A. Age-related differences in social media use, online social support, and depressive symptoms in adolescents and emerging adults. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2023, 28, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-Behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Bonnie, R.J., Backes, E.P., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 25388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, D.; Hobson, B.A.; March, E.; Griffiths, M.D.; Stavropoulos, V. Psychometric properties of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: An analysis using item response theory. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2023, 17, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.A. Sex Differences in the Factors Influencing Korean College Students’ Addictive Tendency Toward Social Networking Sites. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 16, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, S.; Afifi, S.; Suryadevara, V.; Habab, Y.; Hutcheson, A.; Panjiyar, B.K.; Davydov, G.G.; Nashat, H.; Nath, T.S. A Systematic Review of the Association of Internet Gaming Disorder and Excessive Social Media Use With Psychiatric Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents: Is It a Curse or a Blessing? Cureus 2023, 15, e43835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassi, L.; Thomas, K.; Parry, D.A.; Leyland-Craggs, A.; Ford, T.J.; Orben, A. Social Media Use and Internalizing Symptoms in Clinical and Community Adolescent Samples: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, C.K.; Mansolf, M.; Rose, T.; Pila, S.; Cella, D.; Cohen, A.; Leve, L.D.; McGrath, M.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Urquhart, A.; et al. Adolescent Social Media Use and Mental Health in the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 76, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. The relationship between adolescent emotion dysregulation and problematic technology use: Systematic review of the empirical literature. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F.; Rega, V.; Boursier, V. Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, M.E. Multidisciplinary Literary Review: The Relationship Between Social Media and Empathy. Honors Thesis, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Chattanooga, TN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Áfra, E.; Janszky, J.; Perlaki, G.; Orsi, G.; Nagy, S.A.; Arató, Á.; Szente, A.; Alhour, H.A.M.; Kis-Jakab, G.; Darnai, G. Altered functional brain networks in problematic smartphone and social media use: Resting-state fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2023, 18, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshchenko, S.Y. Neurobiological risk factors for problematic social media use as a specific form of Internet addiction: A narrative review. World J. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, L.; Helvich, J.; Mikoska, P.; Juklova, K. I Can’t Understand You, Because I Can’t Understand Myself: The Interplay between Alexithymia, Excessive Social Media Use, Empathy, and Theory of Mind. Psihol. Teme 2023, 32, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, D.; Yan, J. Effect of SNS addiction on prosocial behavior: Mediation effect of fear of missing out. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1490188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Herrero-Roldán, S.; Rodriguez-Besteiro, S.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Digital Device Usage and Childhood Cognitive Development: Exploring Effects on Cognitive Abilities. Children 2024, 11, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachmann, B.; Sindermann, C.; Sariyska, R.Y.; Luo, R.; Melchers, M.C.; Becker, B.; Cooper, A.J.; Montag, C. The Role of Empathy and Life Satisfaction in Internet and Smartphone Use Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, F.M. The Relationship Between Social Media and Empathy; Georgia Southern University: Statesboro, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Errasti, J.; Amigo, I.; Villadangos, M. Emotional Uses of Facebook and Twitter: Its Relation With Empathy, Narcissism, and Self-Esteem in Adolescence. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 120, 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Social Media Included |

|---|---|

| Entertainment | TikTok, Twitch, Facebook |

| Sharing content | Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest |

| Profiling | Snapchat |

| General Purpose |

| Diagnostic Categories | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| ADHD | 23 |

| ASD | 4 |

| Tic Disorder | 3 |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorder | 18 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 18 |

| OCD | 8 |

| Behavioral Disorder | 65 |

| Mood Disorder | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Accorinti, I.; Mutti, G.; Fantozzi, P.; Milone, A.; Sesso, G.; Tolomei, G.; Valente, E.; Narzisi, A.; Martinelli, E.; Cordella, M.R.; et al. Social Media Engagement and Usage Patterns, Mental Health Comorbidities, and Empathic Measures in an Italian Adolescent Sample: A Comparative Study. Children 2025, 12, 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091226

Accorinti I, Mutti G, Fantozzi P, Milone A, Sesso G, Tolomei G, Valente E, Narzisi A, Martinelli E, Cordella MR, et al. Social Media Engagement and Usage Patterns, Mental Health Comorbidities, and Empathic Measures in an Italian Adolescent Sample: A Comparative Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091226

Chicago/Turabian StyleAccorinti, Ilaria, Giulia Mutti, Pamela Fantozzi, Annarita Milone, Gianluca Sesso, Greta Tolomei, Elena Valente, Antonio Narzisi, Edoardo Martinelli, Maria Rosaria Cordella, and et al. 2025. "Social Media Engagement and Usage Patterns, Mental Health Comorbidities, and Empathic Measures in an Italian Adolescent Sample: A Comparative Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091226

APA StyleAccorinti, I., Mutti, G., Fantozzi, P., Milone, A., Sesso, G., Tolomei, G., Valente, E., Narzisi, A., Martinelli, E., Cordella, M. R., Masi, G., & Berloffa, S. (2025). Social Media Engagement and Usage Patterns, Mental Health Comorbidities, and Empathic Measures in an Italian Adolescent Sample: A Comparative Study. Children, 12(9), 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091226