Effective Interventions in the Treatment of Self-Harming Behavior in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Injurious Behaviors in Children and Adolescents with ASD

1.2. Prevalence and Relevance of the Problem

1.3. Treatment

1.4. Review of the State of the Art

1.5. Limitations and Gaps

1.6. The Current Study

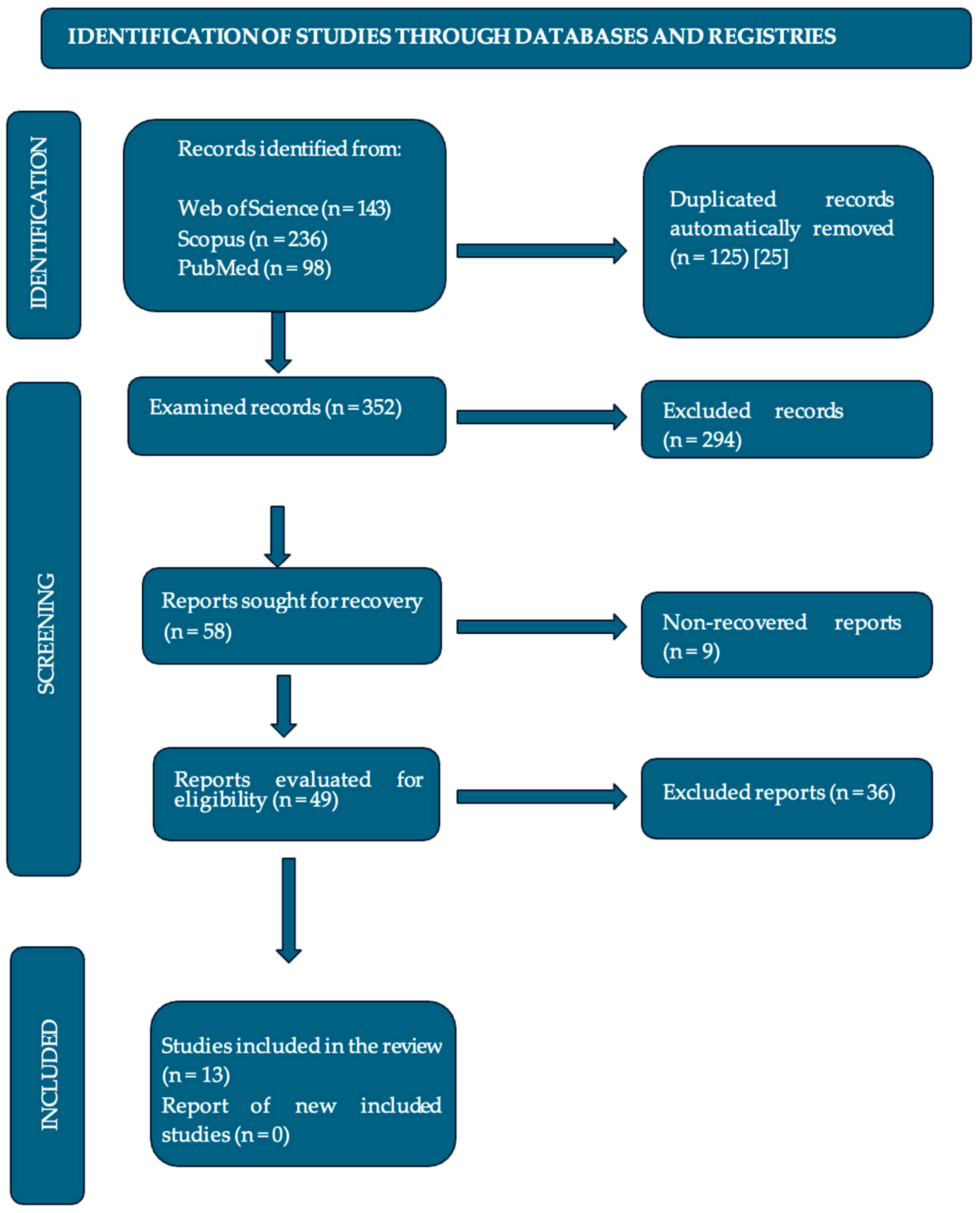

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Studies

2.2. Extraction of Studies

2.3. Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Study and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Overview of Interventions

Effectiveness of Interventions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Celis Alcalá, G.; Ochoa Madrigal, M.G. Trastorno del espectro autista (TEA). Rev. De La Fac. De Med. 2022, 65, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistican Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas, A. Psicofarmacología del TEA. In Guía Esencial De Psicofarmacología Del Niño y Del Adolescente, 2nd ed.; Soutullo, E.C., Ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 200–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tudela Torras, M.; Abad Más, L. Reducción de las conductas autolesivas y autoestimulatorias disfuncionales en los trastornos del espectro del autismo a través de la terapia ocupacional. Medicina 2019, 79 (Suppl. S1), 38–43. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0025-76802019000200009 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Villarroel, G.; Jerez, C.; Montenegro, M.; Montes, A.M.; Mirko, I.M.; Silva, I. Conductas autolesivas no suicidas en la práctica clínica: Primera parte: Conceptualización y diagnóstico. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2013, 51, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhzami, M.; Chitiyo, M. Using functional communication training to reduce self-injurious behavior for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3586–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, J.L.; Lovullo, S.V. A review of behavioral treatments for self-injurious behaviors of persons with autism spectrum disorders. Behav. Modif. 2008, 32, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erturk, B.; Machalicek, W.; Drew, C. Self-injurious behavior in children with developmental disabilities: A systematic review of behavioral intervention literature. Behav. Modif. 2018, 42, 498–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Benevides, T.; Leiby, B.; Hunt, J.; van Hooydonk, E.; Faller, P.; Mailloux, Z.; Kelly, D. An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 44, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iffland, M.; Livingstone, N.; Jorgensen, M.; Hazell, P.; Gillies, D. Pharmacological interventions for irritability, aggression, and self-injury in autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 10, CD011769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Menéndez, E.; Piqueras, J.; Soto-Sanz, V. Intervenciones cognitivo-conductuales para reducir conductas autolesivas en niños y jóvenes con TEA: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Psicol. Clínica Con Niños Adolesc. 2022, 9, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed on 15 November 2023).[Green Version]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Pérez-Álvarez, M.; Al-Halabí, S.; Inchausti, F.; López-Navarro, E.R.; Muñiz; Montoya-Castilla, I. Tratamientos psicológicos empíricamente apoyados para la infancia y adolescencia: Estado de la cuestión. Psicothema 2021, 33, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzari, C.; Hawani, A.; Ayed, K.B.; Mrayeh, M.; Marsigliante, S.; Muscella, A. The impact of a music-and movement-based intervention on motor competence, social engagement, and behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Children 2025, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flujas-Contreras, J.M.; Chávez-Askins, M.; Gómez, I. Efectividad de las intervenciones psicológicas en Trastorno del Espectro Autista: Una revisión sistemática de meta-análisis y revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. De Psicol. Clínica Con Niños Y Adolesc. 2023, 10, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, M.C.; Taber-Doughty, T.; Wendt, O.; Smalts, S. Using a behavioral approach to decrease self-injurious behavior in an adolescent with severe autism: A data-based case study. Behav. Interv. 2015, 30, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaven, J.; Blakeley-Smith, C.K.; LeGrand, L.J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 53, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, S.; Ruiz, S.; Hwang, J.; Wertalik, J.L.; Moeller, J.; Karal, M.A.; Mulloy, A. Meta-analysis of single-case treatment effects on self-injurious behavior for individuals with autism and intellectual disabilities. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2017, 2, 2396941516688399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, E.; Dowling, S.; Phelps, M.; Findling, R.L. Pharmacotherapy of emotional and behavioral symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 19, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucyshyn, J.; Albin, R.W.; Horner, R.H.; Mann, J.C. Family implementation of positive behavior support for a child with autism. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2007, 9, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P.; Magiati, I.; Charman, T. Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 114, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.; Simmonds, M.; Marshall, D.; Hodgson, R.; Stewart, L.A.; Rai, D.; Wright, K. Intensive behavioural interventions based on applied behaviour analysis for young children with autism: A systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 20, 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Dinsmore, A.; Charman, T. What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism 2024, 18, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takats, S.; Stillman, D.; Cheslack-Postava, F.; Bagdonas, M.; Jellinek, A.; Najdek, T.; Petrov, D.; Rentka, M.; Venčkauskas, A. Zotero (6.0.26) [Windows 10]; Corporation for Digital Scholarship: Vienna, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Weiss, J.A.; Thomson, K.; Burnham Riosa, P.; Albaum, C.; Chan, V.; Maughan, A.; Tablon, P.; Black, K. A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.; Dodson, J.; Strale, F., Jr. Impact of Applied Behavior Analysis on Autistic Children Target Behaviors: A Replication Using Repeated Measures. Cureus 2024, 16, e53372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Gershwin, T.; London, D. Maintaining Safety and Facilitating Inclusion: Using Applied Behavior Analysis to Address Self-Injurious Behaviors Within General Education Classrooms. Beyond Behav. 2019, 28, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabus, A.; Feinstein, J.; Romani, P.; Goldson, E.; Blackmer, A. Management of self-injurious behaviors in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A pharmacotherapy overview. Pharmacotherapy 2019, 39, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.J.; Kendall, P.C.; Wood, K.S.; Kerns, C.M.; Seltzer, M.; Small, B.J.; Lewin, A.B.; Storch, E.A. Cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 77, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minshawi, N.F.; Hurwitz, S.; Fodstad, J.C.; Biebl, S.; Morriss, D.H.; McDougle, C.J. The association between self-injurious behaviors and autism spectrum disorders. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2014, 7, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izurieta-Cossio, M. Programa de Intervención Conductual Para Reducir Conductas Autolesivas en Una Niña Con Diagnóstico de Autismo [Trabajo de Titulación, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia]. Repositorio Institutional UPCH. 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12866/15083 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ghaleiha, A.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Mohammadi, E.; Farokhnia, M.; Modabbernia, A.; Yekehtaz, H.; Ashrafi, M.; Hassanzadeh, E. Riluzole como terapia adyuvante a risperidona para el tratamiento de la irritabilidad en niños con trastorno autista: Un ensayo aleatorizado, doble ciego y controlado con placebo. Paediatr. Drugs 2013, 15, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, F.; Mandy, W.; Seto, M.; Hongo, M.; Tsuchiyagaito, A.; Hirano, Y.; Sutoh, C.; Guan, S.; Nitta, Y.; Ozawa, Y.; et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for autistic adolescents, awareness and care for my autistic traits program: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, C.; Gómez, S.; De Stasio, S.; Berenguer, C. Augmented reality and learning-cognitive outcomes in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Children 2025, 12, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study topic | Narrative review of effective interventions for treatment of self-injurious behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD |

| Population | Children and adolescents with ASD |

| Intervention | Interventions for self-injurious behaviors in ASD (behavioral therapy, occupational therapy-based interventions, ABBA method, etc.) |

| Comparison | Comparison of different types of interventions considering their effectiveness |

| Outcome | Results of interventions will be evaluated in terms of reduction or decrease in self-harming behaviors, improvements in quality of life, or adaptive behavior |

| Study design | Controlled clinical trials, cohort studies, and case–control studies. Longitudinal studies and intervention studies with control groups are the most appropriate for evaluating long-term effectiveness of interventions |

| Pattern | WoS | Scopus | PubMed |

|---|---|---|---|

| (“adolescents”) AND (“children”) AND (“autism spectrum disorder”) AND (“self-injurious behaviors”) AND (“Intervention” OR “Psychological Interventions” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR “TCC” OR “Psychotherapy” OR “Clinical Psychology” OR “Intervention program*” OR “intervention*” OR “treatment program*” OR “therapeutic program*” OR “therapy program*” OR “clinical intervention*” OR “clinical treatment*” OR “psychological treatment*” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy*” OR “ABA therapy” OR “behavioral therap*” OR “ABA” OR “occupational therapy” OR “sensory therapy” OR “sensory integration” OR “effective interventions” OR “ABA behavioral therapy” OR “Family based therapy” OR “asperger” OR “self-harm” OR “self-injurious behavior” OR “interpersonal therapy” OR “Cognitive therapy” OR “behavioral therapy). | 143 | 236 | 98 |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Children and adolescents (up to 18 years old) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Publication must be dated no more than 10 years ago to ensure the relevance and timeliness of the approaches. Studies evaluating interventions designed to reduce or manage self-injurious behaviors. Includes different types of interventions, such as behavioral, cognitive, sensory integration, and educational therapies, among others. Articles presenting quantitative and qualitative results on the effectiveness of interventions. Research directly addressing interventions to treat self-injurious behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD. Studies that clearly describe the methodology used in the intervention (behavioral, pharmacological, sensory, etc.). Articles that include data on the effectiveness of the intervention. No language restrictions. | Studies that focus exclusively on adults with ASD or populations not diagnosed with ASD. Studies that primarily investigate medical or psychological conditions other than ASD, unless they include a significant subgroup of participants with ASD. Studies that do not specifically evaluate interventions targeting self-injurious behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD. Articles not directly related to self-injurious behaviors in ASD. Studies of other disorders or interventions not applicable to ASD. Research without empirical evidence or studies that have not been peer-reviewed. |

| Author(s), Year, Country | Type of Study | Intervention/Therapy | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weiss et al. [26], (2018) Canada | Randomized controlled | Cognitive behavioral therapy | Improvement in emotional regulation and reduction in self-harming behaviors. |

| Peterson et al. [27], (2024) USA | Experimental | Applied behavior analysis and other behavioral interventions | Reduction in self-harming behaviors and other problematic behaviors. |

| Alakhzami & Chitiyo [6], (2022) USA | Experimental | Functional communication training | Reduction in self-harming behaviors. |

| Robinson et al. [28],(2019) USA | Case | Behavioral interventions | Reduction in self-harming behaviors. |

| Sabus et al. [29], (2019) USA | Review | Pharmacotherapy | Pharmacological strategies; effectiveness of risperidone; pharmacotherapy should be combined with behavioral therapy. |

| Wood et al. [30], (2019) USA | Randomized controlled | Cognitive behavioral therapy | Significant decrease in both anxiety and self-injury behaviors. |

| Morano et al. [18], (2017) USA | Meta-analysis | Behavioral treatments | Reduction in self-harming behaviors. |

| Boesch et al. [16], (2015) USA | Case | Behavioral approach | 50% reduction in self-injurious behaviors and effectiveness in severe cases. |

| Minshawi et al. [31], (2014) USA | Observational | Association analysis | Relationship between self-harm and clinical features; key functional assessment for intervention. |

| Schaaf et al. [9], (2013) USA | Randomized controlled | Sensory integration therapy | 40% reduction in self-injurious behaviors; improvement in self-regulation. |

| Izurieta Cossio [32], (2023) Peru | Case | Behavioral intervention | Reduction in self-injurious behaviors; effective individualized intervention. |

| Ghaleiha et al. [33],(2013) Iran | Randomized controlled | Pharmacotherapy | Improvement in irritability and indirect reduction in self-harm. |

| Oshima et al. [34], (2023) Japan | Randomized controlled | Cognitive behavioral therapy | Improvements in emotional self-regulation and reduction in self-harm. |

| Type of Therapy | Overall Effectiveness |

|---|---|

| Behavioral Therapies | Behavioral therapy is highly effective in reducing self-injurious behaviors, especially with applied behavioral intervention (ABA). The best results are seen in young children, although it is also useful in adolescents with moderate self-injurious behaviors. It is especially effective for higher-functioning individuals who can learn new behavioral skills quickly. |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapies | Cognitive behavioral therapies show positive effectiveness in terms of emotional regulation, with significant reductions in self-injurious behaviors, particularly in managing frustration and anxiety. They are especially effective in children and adolescents with greater functional and verbal ability who can benefit from problem-solving and the development of emotional coping skills. |

| Occupational Therapy/Sensory Integration | These therapies are moderately effective, and they are especially useful for people with sensory overreactions. These therapies help reduce self-injurious behaviors related to sensory overload. They are most useful for children and adolescents with sensory difficulties and can also be applied to people with a wider range of functional abilities. |

| Combined Interventions with Medication | These interventions are effective for severe cases of ASD, especially those with emotional or neuropsychiatric comorbidities. Pharmacological interventions may be necessary in combination with other therapies to manage severe or neurochemical symptoms and are more common in adolescents with severe self-injurious behaviors. |

| Combined Interventions (ABA + CBT, SI) | These interventions are highly effective in the combined management of behaviors and emotions, offering integrated improvements that address multiple factors. These interventions are ideal for children and adolescents with ASD, especially those with emotional difficulties and severe self-injurious behaviors, who require a comprehensive approach that addresses both behavioral and emotional aspects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Labarca, P.; Oyanadel, C.; González-Loyola, M.; Peñate, W. Effective Interventions in the Treatment of Self-Harming Behavior in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Children 2025, 12, 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091184

Labarca P, Oyanadel C, González-Loyola M, Peñate W. Effective Interventions in the Treatment of Self-Harming Behavior in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Children. 2025; 12(9):1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091184

Chicago/Turabian StyleLabarca, Pamela, Cristian Oyanadel, Melissa González-Loyola, and Wenceslao Peñate. 2025. "Effective Interventions in the Treatment of Self-Harming Behavior in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review" Children 12, no. 9: 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091184

APA StyleLabarca, P., Oyanadel, C., González-Loyola, M., & Peñate, W. (2025). Effective Interventions in the Treatment of Self-Harming Behavior in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Children, 12(9), 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091184