An Overview and Quality Assessment of European National Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Guideline Quality

3. Results

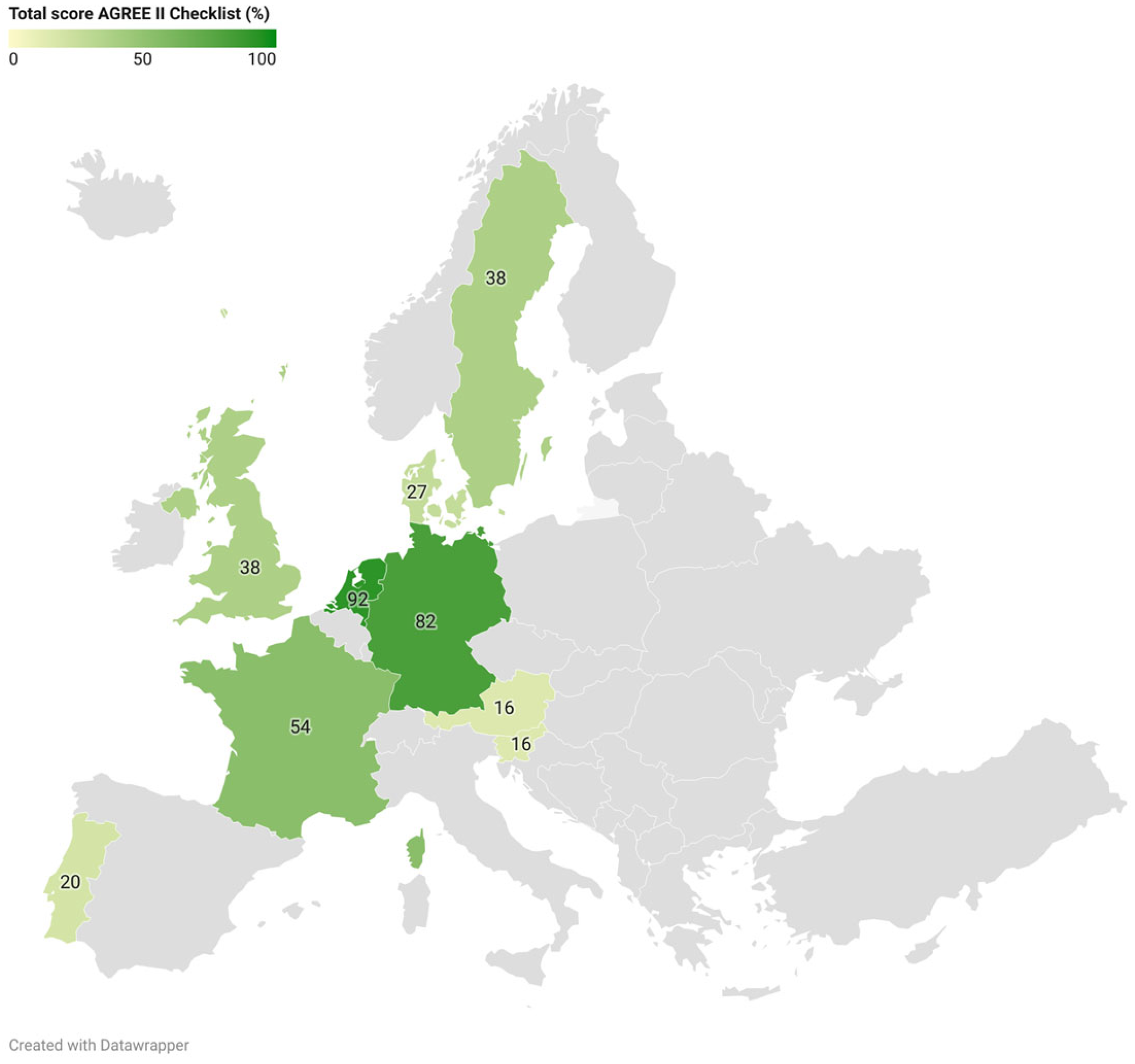

3.1. Guideline Quality: AGREE II

3.2. Guidelines for DDH Screening

3.2.1. Risk Factors for DDH

3.2.2. Clinical Examination (CE)

3.2.3. Imaging

3.3. Guidelines for DDH Treatment

3.3.1. Centered Hips

3.3.2. Decentered Hips

3.3.3. Consolidated Recommendations Across Guidelines

4. Discussion

- (1)

- We urge all (European) countries to develop a national guideline for DDH screening and treatment, using validated tools to ensure good guideline quality, and to publish this guideline in a peer-reviewed journal.

- (2)

- (3)

- Due to the large variation in the timing of screening across European countries, studies comparing initial screening moments are needed to identify the optimal age (range) for DDH screening.

- (4)

- Studies on the (cost-)effectiveness of active monitoring versus abduction treatment for centered DDH are needed.

- (5)

- Evaluation of the optimal timing of treatment initiation and monitoring frequency of DDH should be undertaken.

- (6)

- Identification of the long-term follow-up moments that are needed to ensure quality care is recommended.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaeffer, E.K.; Study Group, I.; Mulpuri, K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Addressing evidence gaps with a multicentre prospective international study. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezateux, C.; Rosendahl, K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet 2007, 369, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bergen, C.J.A.; de Witte, P.B.; Willeboordse, F.; de Geest, B.L.; Foreman-van Drongelen, M.; Burger, B.J.; den Hartog, Y.M.; van Linge, J.H.; Pereboom, R.M.; Robben, S.G.F.; et al. Treatment of centered developmental dysplasia of the hip under the age of 1 year: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline—Part 1. EFORT Open Rev. 2022, 7, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engesæter, I.; Lehmann, T.; Laborie, L.B.; Lie, S.A.; Rosendahl, K.; Engesæter, L.B. Total hip replacement in young adults with hip dysplasia: Age at diagnosis, previous treatment, quality of life, and validation of diagnoses reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register between 1987 and 2007. Acta Orthop. 2011, 82, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Wade, R.G.; Metcalfe, D.; Perry, D.C. Does This Infant Have a Dislocated Hip?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilsdonk, I.; Witbreuk, M.; Van Der Woude, H.J. Ultrasound of the neonatal hip as a screening tool for DDH: How to screen and differences in screening programs between European countries. J. Ultrason. 2021, 21, e147–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, R. Hip Sonography: Diagnosis and Management of Infant Hip Dysplasia, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskaratou, E.D.; Eleftheriades, A.; Sperelakis, I.; Trygonis, N.; Panagopoulos, P.; Tosounidis, T.H.; Dimitriou, R. Epidemiology and Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Scoping Review. Reports 2024, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysta, W.; Dudek, P.; Pulik, Ł.; Łęgosz, P. Screening of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Europe: A Systematic Review. Children 2024, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Cmaj 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Pan, B.; Yang, Q.; Cao, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ding, G.; Tian, J.; Ge, L. A critical appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on insomnia using the RIGHT statement and AGREE II instrument. Sleep. Med. 2022, 100, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, T.; Thielemann, F.; Gerhardt, A.; Gaulrapp, H.; Zierl, A.; Buchholz, S.; Naumann, A.; Winter, B.; Rodens, K. S2k-Guideline Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in the Neonate. Z. Orthop. Unfall 2024, 162, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ocepek, E.; Berden, N.; Brecelj, J. Developmental dysplasia of the hip − guidelines for evaluation and referral in newborns and infants in Slovenia. Slov. Pediatr. 2019, 26, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Aarvold, A.; Perry, D.C.; Mavrotas, J.; Theologis, T.; Katchburian, M. The management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in children aged under three months: A consensus study from the British Society for Children’s Orthopaedic Surgery. Bone Joint J. 2023, 105-b, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, P.B.; van Bergen, C.J.A.; de Geest, B.L.; Willeboordse, F.; van Linge, J.H.; den Hartog, Y.M.; Drongelen, M.H.P.F.-V.; Pereboom, R.M.; Robben, S.G.F.; Burger, B.J.; et al. Treatment of decentered developmental dysplasia of the hip under the age of 1 year: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline—Part 2. EFORT Open Rev. 2022, 7, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francke, A.L.; Smit, M.C.; de Veer, A.J.; Mistiaen, P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, P.; Gangadharan, R.; Poku, D.; Aarvold, A. Cost Analysis of Screening Programmes for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: A Systematic Review. Indian. J. Orthop. 2020, 55, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, K.; Markestad, T.; Lie, R.T.; Sudmann, E.; Geitung, J.T. Cost-effectiveness of alternative screening strategies for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1995, 149, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Organization | Guideline | Year of Publication | Source(s) | Scientific Publication(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Regulation of the Federal Minister for Social Security and Generations (“Verordnung des Bundesministers für soziale Sicherheit und Generationen”) | Child health check-ups under the parent–child passport program (“Eltern-Kind-Pass-Untersuchungen des Kindes”) | 2002, Updated 2013 | https://www.oesterreich.gv.at/themen/familie_und_partnerschaft/eltern-kind-pass/Seite.082211.html#AllgemeineInformationen a | NA |

| Denmark | Danish Health Authority (“Sundhedsstyrelsen”) | Guidelines on preventive health services for children and adolescents (“Vejledning om forebyggende sundhedsydelser til børn og unge”) | 2019, Version 3.0 | https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2019/vejledning-om-forebyggende-sundhedsydelser-til-boern-og-unge a | NA |

| France | French National Health Authority (“Haute Autorité de Santé”) | Developmental dysplasia of the hip: screening | 2013 | https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1680275/en/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip-screening a | NA |

| Germany | German Society for Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery (“Deutschen Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie (DGOU)”) | S2k guideline on hip dysplasia—new registry (“S2k-Leitlinie Hüftdysplasie—neue Register-Nr.: 187-054”) | 2021, Version 2.0 | https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/187-054 a | Seidl et al. (2024) [11] |

| Portugal | Portuguese Society of Paediatric Orthopaedics (SPOT) | Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) screening protocol | Unknown | Document provided by SPOT | NA |

| Slovenia | NR | Developmental dysplasia of the hip −guidelines for evaluation and referral in newborns and infants in Slovenia | 2019 | http://www.slovenskapediatrija.si/sl-si/pdf_datoteka?revija=44&clanek=1263 a | Ocepek et al. (2019) [12] |

| Sweden | National Board of Health and Welfare | Guidance for child health services (“Vägledning för barnhälsovården”) | 2014 | https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/vagledning/2014-4-5.pdf a | NA |

| United Kingdom | British Society of Children’s Orthopaedic Surgery (BSOS) | Newborn and infant physical examination (NIPE) screening programme handbook | Updated 2024 | https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/newborn-and-infant-physical-examination-programme-handbook/newborn-and-infant-physical-examination-screening-programme-handbook#screening-examination-of-the-hips a | Aarvold et al. (2023) [13] |

| The Netherlands | Dutch Orthopaedic Society (“Nederlandse Orthopedische Vereniging (NOV)”) | DDH (developmental dysplasia of the hip) in children under one year (“DDH (dysplastische heupontwikkeling) bij kinderen onder één jaar”) | 2020 | https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/ddh_dysplastische_heupontwikkeling_bij_kinderen_onder_n_jaar/startpagina_-_ddh.html a | Van Bergen et al. (2022) [3] De Witte et al. (2022) [14] |

| Guideline Origin (Year) | Scope and Purpose (%) | Stakeholder Involvement (%) | Rigor of Development (%) | Clarity of Presentation (%) | Applicability (%) | Editorial Independence (%) | Total Score (%) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (2013) | 50 | 6 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Denmark (2019) | 56 | 53 | 8 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| France (2013) | 89 | 78 | 34 | 75 | 19 | 29 | 54 |

| Germany (2021) | 100 | 89 | 56 | 92 | 56 | 100 | 82 |

| Portugal (UNK) | 50 | 3 | 3 | 61 | 2 | 0 | 20 |

| Slovenia (2019) | 25 | 0 | 3 | 61 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| Sweden (2014) | 72 | 72 | 29 | 53 | 4 | 0 | 38 |

| United Kingdom (2024) | 75 | 31 | 27 | 75 | 10 | 8 | 38 |

| The Netherlands (2020) | 100 | 86 | 81 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 92 |

| Mean score (%) | 69 | 46 | 27 | 67 | 20 | 26 | 43 |

| Country | Clinical Examination (CE) | Imaging | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE | Timing and Place | CE Factors | Risk Factors | Imaging | Type | Technique | US System | Timing | |

| Austria | Yes | Week 4–7 | NR | NR | Yes | NR | NR | Universal | Week 1 and week 6–8 |

| Denmark | Yes | After birth (midwife) and week 5 (GP) | Barlow, Ortolani, hip mobility | Breech presentation, family history (1st degree), congenital limb deformities | NR, based on regional recommendations | NR | NR | Selective | NR |

| France | Yes | At birth, at discharge, monthly until 3 months, each medical examination until walking age | Limited hip abduction, instability, leg length discrepancy, asymmetry of skin folds | Breech presentation, family history (1st degree), other orthopedic abnormalities | Yes | Ultrasound | Graf method | Selective | Age of 1 month when RF and/or abnormal CE |

| Germany | Yes | Day 3–10 (hospital/pediatric practice) | Limited hip abduction, leg length discrepancy | Breech presentation, family history | Yes | Ultrasound | Graf method | Universal | (1) Week 4–5 all newborns, ≤week 8 (2) Day 3–10 for infants with RF and/or abnormal CE |

| Portugal | Yes | Every consultation from birth until walking | Barlow, Ortolani, limited hip abduction | Breech presentation, family history, history of oligohydramnios, congenital foot deformities, congenital torticollis, polymalformative syndrome, asymmetric skin folds | Yes | Ultrasound | NR | Selective | (1) Week 6 when RF (2) Immediately when signs of hip instability |

| Slovenia | Yes | Within the first hours or days of life and every follow-up examination | Barlow, Ortolani, Galeazzi | Breech presentation, family history, syndromic anomalies, torticollis, foot deformities | Yes | Ultrasound | Graf method | Universal | (1) Week 6 all newborns (2) At maternity hospital when RF or abnormal CE NB: Graf ≥ 2A or clinically decentered hips require referral to a pediatric outpatient clinic by week 3 (but no later than month 3). |

| Sweden | Yes | After discharge from the maternity ward, week 4, 6 months, 10–12 months, 18 months | Barlow, Ortolani, limited hip abduction, leg length discrepancy, deviations in walking pattern | NR | Yes | NR | NR | Selective | NR |

| United Kingdom | Yes | At birth and week 6–8 | Barlow, Ortolani, leg length discrepancy, limited hip abduction | Breech position at or after 36 completed weeks of pregnancy or at time of birth between 28 weeks and term, family history (1st degree) | Yes | Ultrasound | Graf method | Selective | (1) Within 4–6 weeks when RF and/or abnormal CE or by 40+0 weeks corrected age for babies who are born <34 + 0 weeks. (2) If screen positive results at the 6–8-week screening, then direct referral to a pediatric orthopedic surgeon and be seen by 10 weeks of age. |

| The Netherlands | Yes | ≤month 1 | Limited hip abduction (<70°), abduction difference ≥20°, Galeazzi | Breech presentation after week 32, family history | Yes | Ultrasound | Graf method | Selective | (1) 3 months when RF (2) Within 2 weeks when abnormal CE |

| Country | Treatment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDH Type | Timing | Type | Prerequisite | Device | Monitoring Frequency | Duration | Endpoint | If Unresolved | Follow-Up | |

| Germany | Centered | <Week 1 after diagnosis | AT | NR | Orthotic device with hip flexion 100–110° and limits hip abduction to 50–60° | CE and US checks every 4–6 weeks | According to endpoint | Normalization (alpha > 60°) | NR | CE and X-ray at age 2 years |

| Decentered | NR | AT or CR | NR | Orthotic device or CR followed by a hip spica cast in a squatting position | AT: CE and US every 4–6 weeks | Hip spica cast for 4–6 weeks after a successful reduction |

|

| CE and X-ray at age 2 years | |

| Slovenia | Centered | <week 6, no later than month 3 | AT | Adequate hip abduction (to prevent AVN) | Ottobock orthoses | NR | Several weeks to months | Normalization | NR | NR |

| Decentered | <week 6, no later than month 3 | AT | Adequate hip abduction (to prevent AVN) | Ottobock orthoses | NR | Several weeks | Normalization |

| NR | |

| United Kingdom | Centered | NR | AT | For 2A hips: >2 weeks old | Harness/splint | CE every 2 weeks; US every 2–4 weeks | According to endpoint | Normalization (alpha > 60°) | NR | X-ray at age 2 years |

| Decentered | <2 weeks after diagnosis | AT | NR | Harness/splint | NR | According to endpoint | At least 6 weeks after the hip is centered | Failing to center: Discontinue treatment for 3 weeks | X-ray at age 2 years | |

| The Netherlands | Centered | - No improvement after 6 weeks of AM - No normalization after 12 weeks of AM | AM or AT | NR | Pavlik harness or alternative when age >6 months | CE and US every 6 weeks | According to endpoint | Normalization or age 1 year | NR | X-ray at the age of 1, 3, and 5 years |

| Decentered | NR | AT | NR | Pavlik-harness or alternative when age > 6 months |

|

| Normalization or age 1 year |

| X-ray at the age of 1, 3, 5, 10, and 18 years | |

| Screening (n = 9 Guidelines) | |

| CE First examination Follow-up examinations Factors a | Yes, universal Birth—Week 7 Universal, up to the age of 18 months Barlow, Ortolani, Galeazzi, limited hip abduction |

| Imaging RF for selective imaging Modality Timing | Yes, selective (6/9) or universal (3/9) +CE, breech presentation, family history, other orthopedic deformities NR (3/9), US (6/9; Graf method (5/6)) Selective: +CE: Birth—Week 10 +RF: Week 4–Week 12 Universal: Week 1—Week 6 (depending on +CE/RF) |

| Treatment (n = 4 guidelines) | |

| Centered DDH Technique Start of treatment Follow-up (CE/US) Endpoint Long-term follow-up | Abduction treatment (3/4) or active monitoring (1/4) Week 2–Week 12 2–6 weeks interval Normalization (-angle > 60) Radiographs (age: varying from 1 up to 5 years) |

| Decentered DDH Technique Start of treatment Follow-up (CE/US) Endpoint Long-term follow-up | Abduction treatment (4/4) or closed reduction (1/4) Week 2–Week 12 4–6 weeks interval Normalization (-angle > 60) If lateralization persists: reduction (closed or open), followed by spica cast Radiographs (age: varying from 1 up to 18 years) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mulder, F.E.C.M.; van Kouswijk, H.W.; Witlox, M.A.; Mathijssen, N.M.C.; de Witte, P.B. An Overview and Quality Assessment of European National Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Children 2025, 12, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091177

Mulder FECM, van Kouswijk HW, Witlox MA, Mathijssen NMC, de Witte PB. An Overview and Quality Assessment of European National Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Children. 2025; 12(9):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091177

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulder, Frederike E. C. M., Hilde W. van Kouswijk, M. Adhiambo Witlox, Nina M. C. Mathijssen, and Pieter Bas de Witte. 2025. "An Overview and Quality Assessment of European National Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip" Children 12, no. 9: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091177

APA StyleMulder, F. E. C. M., van Kouswijk, H. W., Witlox, M. A., Mathijssen, N. M. C., & de Witte, P. B. (2025). An Overview and Quality Assessment of European National Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Children, 12(9), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091177