Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome Among Polish Nurses and Midwives: A Cross-Sectional National Survey

Abstract

Highlights

- 94.5% of nurses had heard of Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS), but only 5.5% received formal training;

- 27.3% experienced emotional overload while caring for a crying infant;

- Older nurses showed better knowledge of colic and safer coping strategies;

- 92.7% expressed interest in SBS and infant crying management training;

- Only 29.1% believed mothers are informed about SBS in maternity wards.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- I.

- Section 1 covered general questions such as year of birth, work experience, average monthly working hours, education, specialization, workplace, and number of children.

- II.

- Section 2 included 14 questions assessing knowledge about Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS).

- III.

- Section 3 focused on strategies for coping with a crying baby.

3. Results

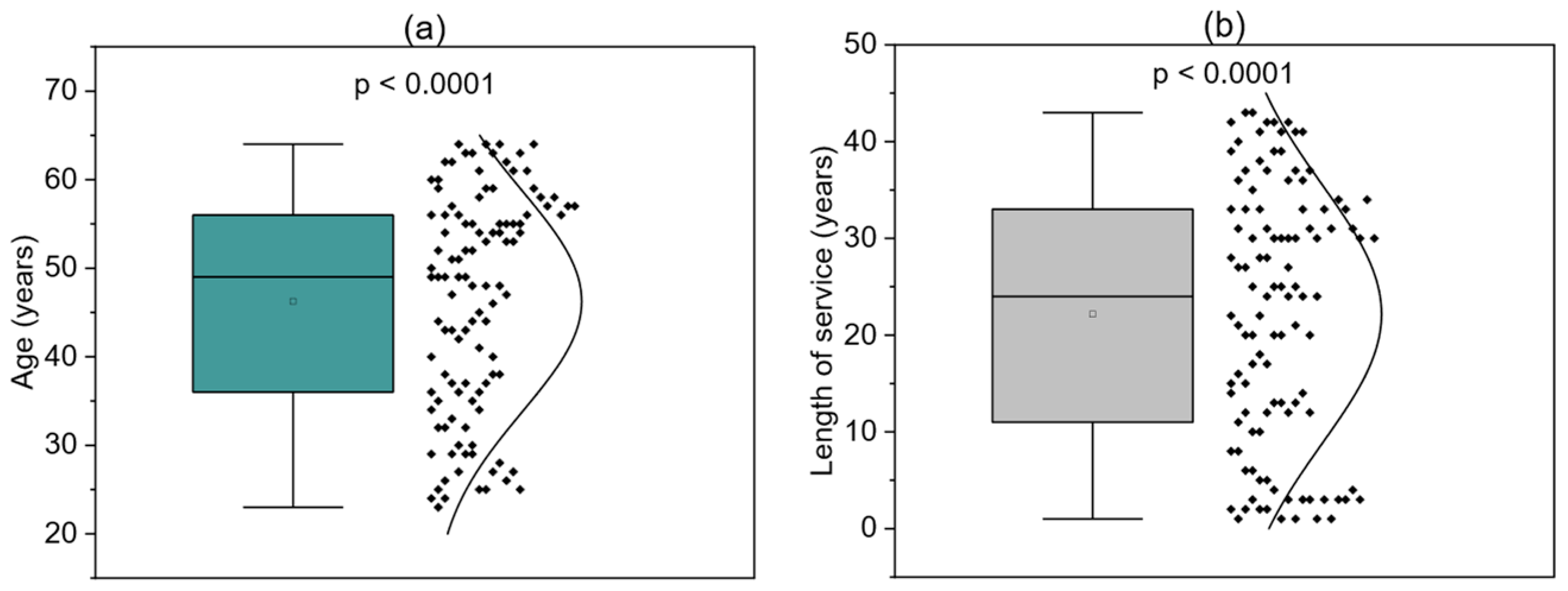

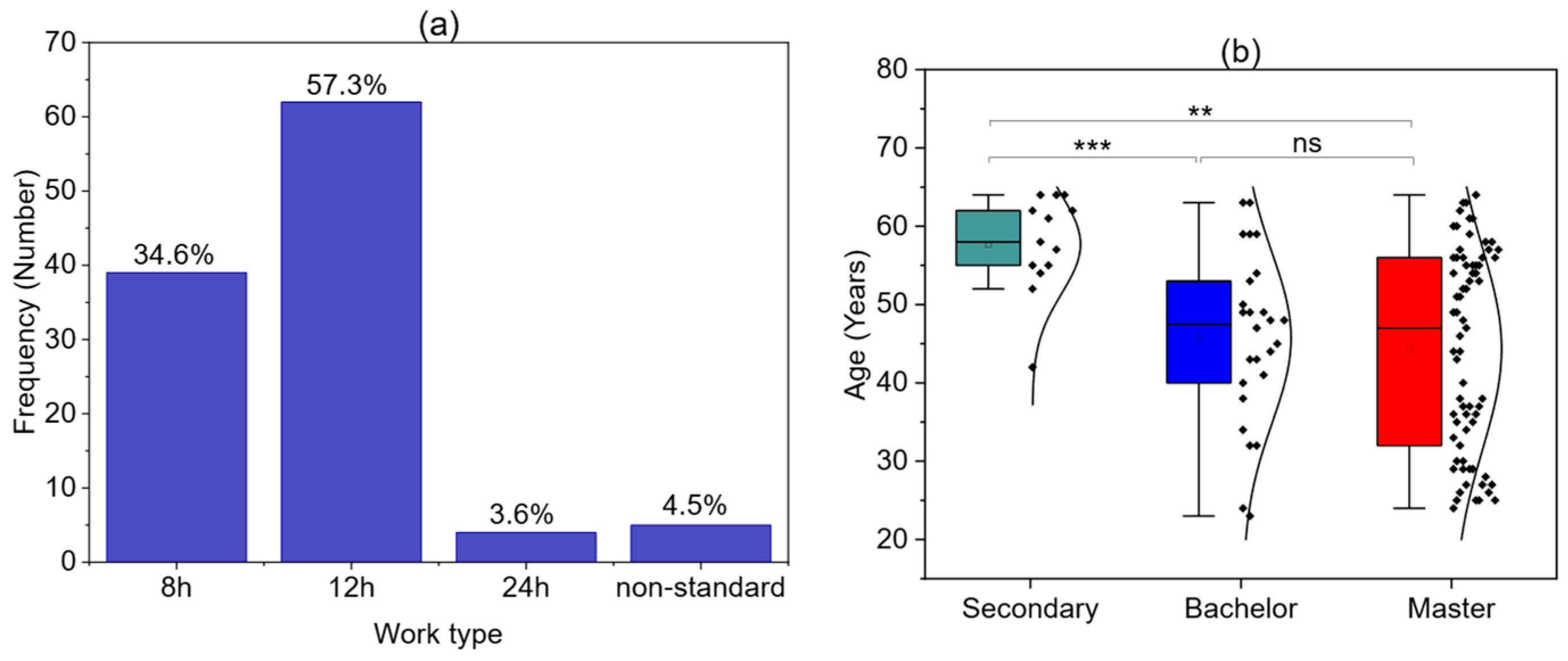

3.1. Respondent Demographics

3.2. Respondents’ Knowledge of SBS

3.3. Ways of Coping with a Crying Baby

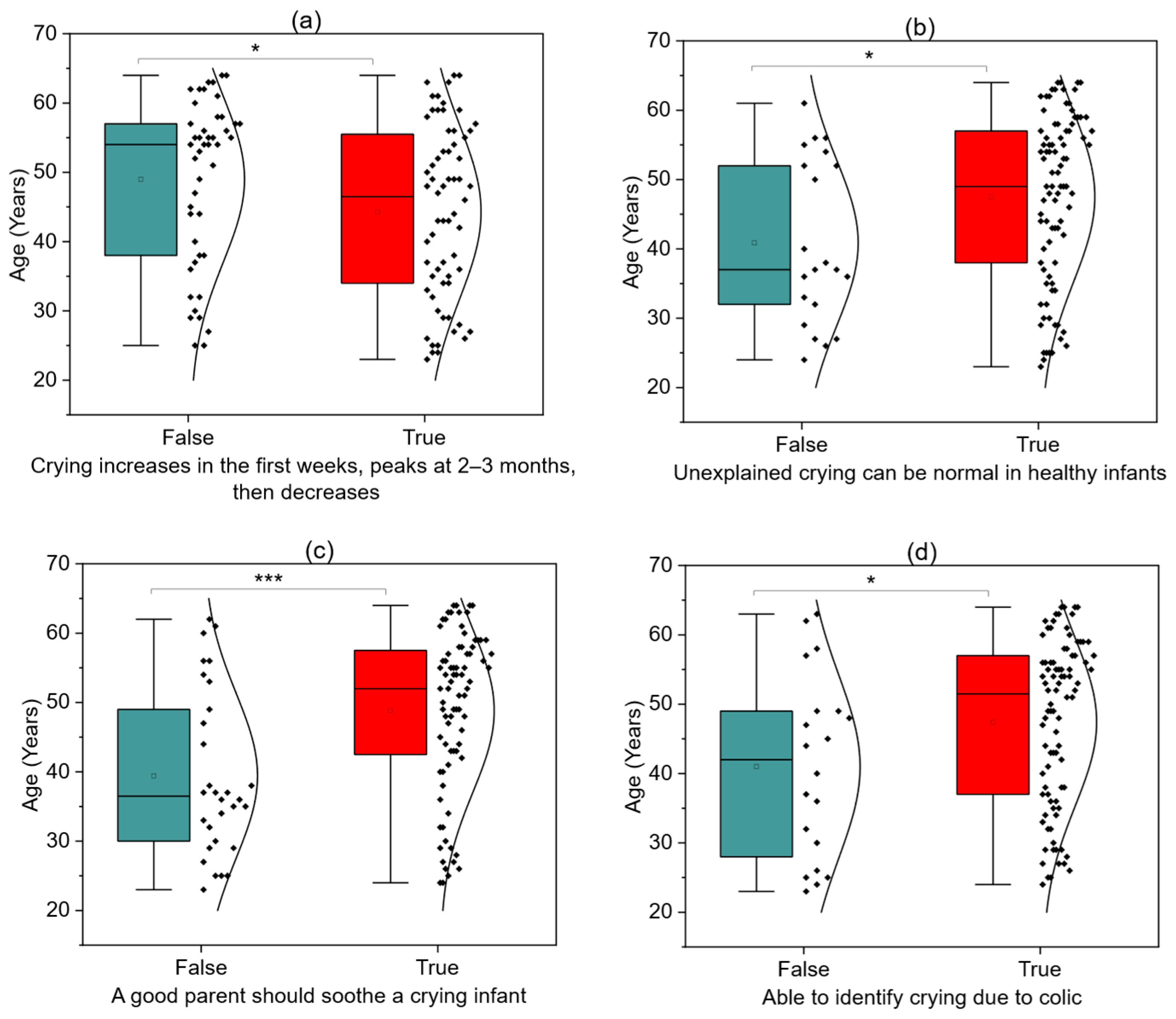

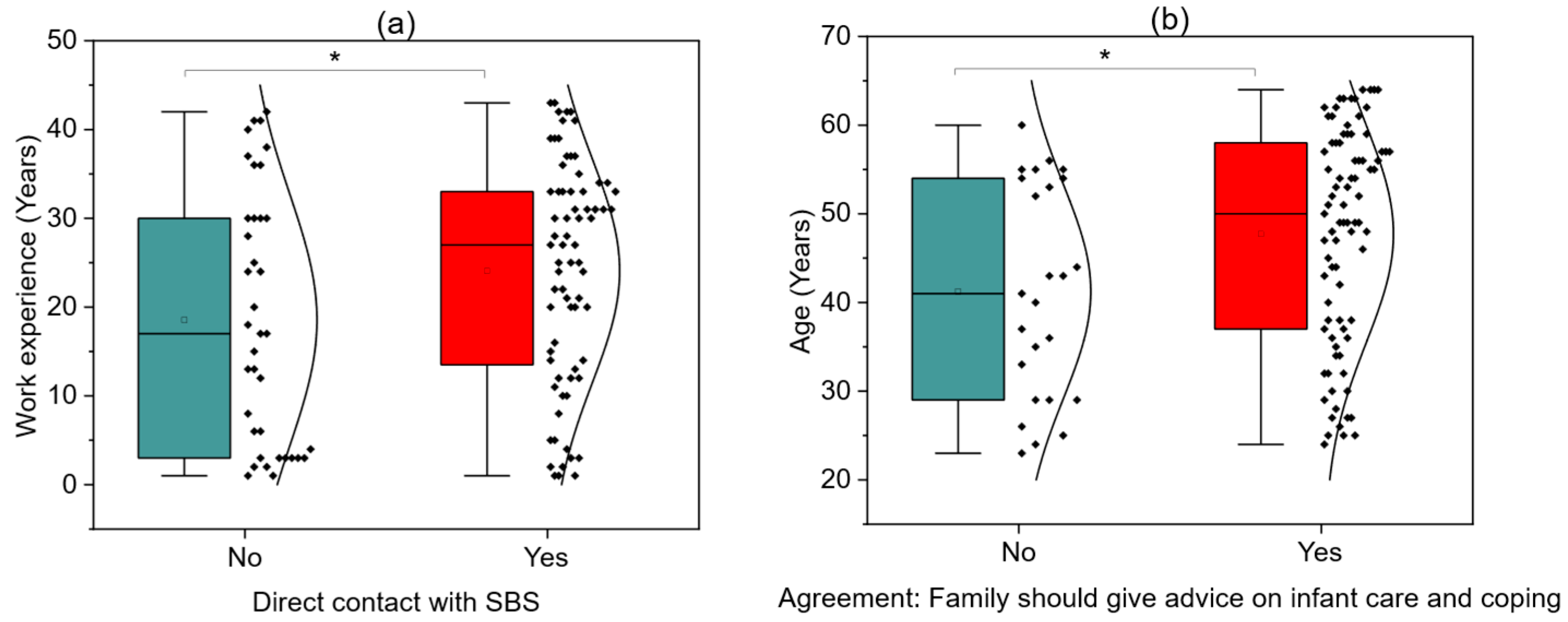

3.4. Factors Associated with SBS Knowledge and Perceptions

3.5. Breaking Point Situations and Factors Associated with Loss of Emotional Control

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Integrating mandatory SBS-related modules into undergraduate nursing and midwifery curricula.

- Offering regular continuing professional development sessions on SBS recognition, prevention, and parental education.

- Encouraging peer-to-peer mentoring within hospital units to facilitate knowledge transfer from more experienced to younger staff.

- Developing structured parental education programs that promote safe coping strategies for infant crying and raise awareness of the dangers of shaking.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thakir, E.M.; Jumaah, L.F.; Younis, M.I. Evaluation of Mothers Knowledge about Shaken Baby Syndrome. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 30, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichon, M. Shaken baby syndrome: What certainty do we have? Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2017, 33, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, S.K.; Estrada, C.; Greenberg, S.D.L. Acceptance of Shaken Baby Syndrome and Abusive Head Trauma as Medical Diagnoses. J. Pediatr. 2016, 177, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squier, W. Retinodural haemorrhage of infancy, abusive head trauma, shaken baby syndrome: The continuing quest for evidence. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2024, 66, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, S.; Majdanik, S.; Glowinska, A.; Majdanik, E. Trauma in a shaken infant? A case study. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 55, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, K.; Ricken, T.; Feld, D.; Helmus, J.; Hahnemann, M.; Schenkl, S.; Muggenthaler, H.; Pfeiffer, H.; Banaschak, S.; Karger, B.; et al. Fractures and skin lesions in pediatric abusive head trauma: A forensic multi-center study. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2022, 136, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pierce, M.C.; Kaczor, K.; Aldridge, S.; O’Flynn, J.; Lorenz, D.J. Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 67–74, Erratum in Pediatrics 2010, 125, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irazuzta, J.E.; McJunkin, J.E.; Danadian, K.; Arnold, F.; Zhang, J. Outcome and cost of child abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 1997, 21, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.G.; Bennett, S.; King, W.J. Prevention of shaken baby syndrome: Never shake a baby. Paediatr. Child Health 2004, 9, 319–321. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Coody, D.; Brown, M.; Montgomery, D.; Flynn, A.; Yetman, R. Shaken baby syndrome: Identification and prevention for nurse practitioners. J. Pediatr. Health Care 1994, 8, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, C. Shaken baby syndrome education: A role for nurse practitioners working with families of small children. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2006, 20, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, R.G.; Barr, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Conway, J.; Catherine, N.; Brant, R. Do educational materials change knowledge and behaviour about crying and shaken baby syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2009, 180, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, V.; Ortiz, A.R.A.; Marq, A.D.; Mostermans, E.; Marichal, M.; Bailhache, M. Childminder knowledge of shaken baby syndrome and the role played by childminders in prevention: An observational study in France. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 31, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeifman, D.M.; St James-Roberts, I. Parenting the Crying Infant. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glowinski, S.; Glowinska, A. Unveiling the Abusive Head Trauma and Shaken baby Syndrome: A Comprehensive Wavelet Analysis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2025, 107, 107862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowska, U.; Paniczek, M.; Ledwoń, M.; Tyrała, K.; Skupnik, R.; Jośko-Ochojska, J. Zespół dziecka potrząsanego w świadomości rodziców i personelu medycznego w Polsce. Pediatr. Pol. 2015, 90, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Franczak Young, A.; Kwiatkowska, K. Neurological and psychological effects in Shaken Baby Syndrome. Szt. Leczenia 2019, 1, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, R.; Canter, J.; Patrick, P.A.; Daley, N.; Butt, N.K.; Brand, D.A. Parent education by maternity nurses and prevention of abusive head trauma. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e1164–e1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M.; DeGuehery, K.A. Shaken baby syndrome education program: Nurses making a difference. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child. Nurs. 2008, 33, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakieła, K.; Curyl, K. Udział pielęgniarki w rozpoznawaniu syndromu dziecka maltretowanego, przyjętego na oddział chirurgii dziecięcej. Pielęgniarstwo Chir. I Angiol.Surg. Vasc. Nurs. 2011, 3, 125–131. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, K.; Le, K.; Martin, K.D.; Shah, N.; Leventhal, J.M.; Colson, E. Impact of an educational intervention on caregivers’ beliefs about infant crying and knowledge of shaken baby syndrome. Acad. Pediatr. 2011, 11, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Campaign for a Violence-Free Childhood. Available online: https://www.polskieradio.pl/395/7789/artykul/3433258,polish-parliament-launches-campaign-to-combat-child-abuse-and-raise-awareness-against-violence (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Mian, M.; Shah, J.; Dalpiaz, A.; Schwamb, R.; Miao, Y.; Warren, K.; Khan, S. Shaken Baby Syndrome: A review. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2014, 34, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnier, C.; Mesples, B.; Gressens, P. Animal models of shaken baby syndrome: Revisiting the pathophysiology of this devastating injury. Pediatr. Rehabil. 2004, 7, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnie, J.W.; Blumbergs, P.C.; Manavis, J.; Turner, R.J.; Helps, S.; Vink, R.; Byard, R.W.; Chidlow, G.; Sandoz, B.; Dutschke, J.; et al. Neuropathological changes in a lamb model of non-accidental head injury (the shaken baby syndrome). J. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 19, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhaime, A.C.; Gennarelli, T.A.; Thibault, L.E.; Bruce, D.A.; Margulies, S.S.; Wiser, R. The shaken baby syndrome. A clinical, pathological, and biomechanical study. J. Neurosurg. 1987, 66, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, J.; Willey, E.; Galaznik, J.; Lee, I.W.; Luttner, S. Biomechanical evaluation of head kinematics during infant shaking versus pediatric activities of daily living. J. Forensic Biomech. 2011, 2, E60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Confer, J.S.; Wayman, L.T.; Havens, K.L. High G-Forces in Unintentionally Improper Infant Handling: Implications for Shaken Baby Syndrome Diagnosis. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.statsoft.com (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Alabdullah, A.A.S.; Ibrahim, H.K.; Aljabal, R.N.; Awaji, A.M.; Al-Otaibi, B.A.; Al-Enezi, F.M.; Al-Qahtani, G.S.; Al-Shahrani, H.H.; Al-Mutairi, R.S. Awareness of Shaken Baby Syndrome among Saudi Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.A.; Shaker, N.Z.; Aziz, G.K. Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome among Hospital Nurses in Erbil City. Erbil J. Nurs. Midwifery 2021, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. The neonatal nurse’s role in preventing abusive head trauma. Adv. Neonatal Care 2014, 14, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 46.25 (12.44) [43.90; 48.61] 49 23–64 | Working time per month [hours] | 158.83 (28.45) [153.45; 164.20] 160 35–280 |

| Length of service [years] | 22.17 (13.34) [19.65; 24.69] 24 1–43 | Number of children | 0 children—28 (25.45%) 1 child—16 (14.55%) 2 children—46 (41.82%) 3 children—15 (13.64%) 4 and more—5 (4.55%) |

| Questions | Answers | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 104 (94.54%) |

| No | 6 (5.46%) | |

| Shake | 86 (78.18%) |

| Falling off table | 24 (21.82%) | |

| At university | 39 (35.45%) |

| In training | 34 (30.91%) | |

| At work | 32 (29.09%) | |

| Not heard | 5 (4.55%) | |

| Shake | 93 (84.55%) |

| Falling off table | 17 (15.45%) | |

| up to 30 | 7 (6.36%) |

| from 31 to 60 | 18 (16.36%) | |

| from 61 to 100 | 20 (18.18%) | |

| from101 to200 | 26 (23.64%) | |

| from 201 to300 | 10 (9.09%) | |

| >300 | 29 (26.36%) | |

| up to 9% | 69 (62.73%) |

| from 10 to 18% | 35 (31.82%) | |

| from 19 to 40% | 5 (4.55%) | |

| from 41 to 50% | 1 (0.91%) | |

| Yes, personally | 19 (17.27%) |

| From colleagues | 12 (10.91%) | |

| From media (TV, Internet) | 41 (37.27%) | |

| No | 38 (34.55%) |

| Questions | Answers | |

|---|---|---|

| Irritability | Yes 97 (88.18%), No 13 (11.82%) |

| Somnolence | Yes 74 (67.27%), No 36 (32.73%) | |

| Feeding difficulties | Yes 94 (85.45%), No 16 (14.55%) | |

| Fretful and crying | Yes 92 (83.64%), No 18 (16.36%) | |

| Emesis | Yes 100 (100.00%), No 0 (0.00%) | |

| Pallor and cyanosis | Yes 71 (64.55%), No 39 (35.45%) | |

| Sleep disorders | Yes 106 (96.36%), No 4 (3.64%) | |

| Epileptic seizures | Yes 98 (89.09%), No 12 (10.91%) | |

| Loss of consciousness | Yes 98 (89.09%), No 12 (10.91%) | |

| Retinal abnormalities | Yes 90 (81.82%), No 20 (18.18%) | |

| Motor impairment | Yes 104 (94.55%), No 6 (5.45%) | |

| up to 20% | 33 (30.00%) |

| from 21 to 30% | 39 (35.45%) | |

| from 31 to 40% | 25 (22.73%) | |

| from 41 to 50% | 13 (11.82%) | |

| Cohabitant/Concubine | 55 (50.00%) |

| Mother | 36 (32.73%) | |

| Father | 16 (14.54%) | |

| Grandmother/Grandfather | 2 (1.81%) | |

| Caregiver | 1 (0.91%) | |

| Increased crying | Yes 106 (96.36%), No 4 (3.64%) |

| Financial situation | Yes 48 (43.64%), No 62 (56.36%) | |

| Stress at work/marriage | Yes 87 (79.09%), No 23 (20.91%) | |

| Child’s illness | Yes 54 (49.09%), No 56 (50.91%) | |

| Alcohol/drugs/stimulants | Yes 105 (95.45%), No 5 (4.55%) | |

| Domestic violence | Yes 108 (98.18%), No 2 (1.82%) | |

| Mother depression | Yes 93 (84.55%), No 17 (15.45%) | |

| Yes, I’m sure | 7 (6.36%) |

| There is such a possibility | 55 (50.00%) | |

| I don’t think so | 29 (26.36%) | |

| Definitely not | 14 (12.73) | |

| Yes, I’m sure | 13 (11.82%) |

| There is such a possibility | 52 (47.27%) | |

| I don’t think so | 33 (30.00%) | |

| Definitely not | 12 (10.91%) | |

| I always kept calm | 80 (72.73%) |

| There was such a “breaking point” situation | 30 (27.27%) |

| Questions | Answers | |

|---|---|---|

| Babies cry more often in the late afternoon or evening. | True 73 (66.36%); False 37 (33.64%) |

| Infant crying intensifies in the first few weeks of life, peaks around 2–3 months, and then decreases. | True 64 (58.18%); False 46 (41.82%) | |

| A healthy baby sometimes cries unexpectedly or without an obvious reason. | True 89 (80.91%); False 21 (19.09%) | |

| Do you think it is normal for infants to cry more than 2 h a day? | True 44 (40.00%); False 66 (60.00%) | |

| Sometimes a crying baby may seem to be in pain, even though they are not. | True 89 (80.91%); False 21 (19.09%) | |

| Sometimes healthy infants can cry for several hours a day. | True 48 (43.64%); False 62 (56.36%) | |

| You can step away from a crying baby when their crying becomes frustrating. | True 35 (31.82%); False 75 (68.18%) | |

| A good parent should be able to soothe their crying baby. | True 80 (72.73%); False 30 (27.27%) | |

| Soothe the crying baby, hold them in your arms | True 110 (100.00%); False 0 (0.00%) |

| Ask another person for help—relatives, parents, in-laws. | True 107 (97.27%); False 3 (2.73%) | |

| Call an ambulance. | True 27 (24.55%); False 83 (75.45%) | |

| Put the crying baby in the crib and go to another room. | True 7 (6.36%); False 104 (93.64%) | |

| Put the crying baby in the crib, stay in the same room (wear headphones and let the baby cry). | True 16 (14.55%); False 94 (85.45%) | |

| up to 0.5 h | 30 (27.27%) |

| from 0.5 to 1 h | 26 (23.64%) | |

| from 1 to 2 h | 5 (4.55%) | |

| all the time | 49 (44.55%) | |

| Can infant colic be the cause of prolonged crying lasting even several months? | Yes 100 (90.91%); No 10 (9.09%) |

| Can you recognize crying caused by colic in a baby? | Yes 90 (81.82%); No 20 (18.18%) | |

| Can infant colic cause a parent to feel irritable, exhausted, or overwhelmed? | Yes 105 (95.45%); No 5 (4.55%) |

| Questions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes 7 (6.36%); No 103 (93.64%) | |

| Yes 6 (5.45%); No 104 (94.54%) | |

| Yes 102 (92.73%); No 8 (7.27%) | |

| Yes 52 (47.27%); No 46 (41.82%) There is no time for that 12 (10.91%) | |

| Yes 32 (29.09%); No 72 (65.45%) There is no time for that 6 (5.45%) | |

| Maternity ward | Yes 100 (90.91%); No 10 (9.09%) |

| Prenatal class | Yes 107 (97.27%); No 3 (2.73%) | |

| General practitioner (GP) | Yes 103 (93.64%); No 7 (6.36%) | |

| Close circle | Yes 76 (69.09%); No 34 (30.91%) | |

| Family | Yes 85 (77.67%); No 35 (22.73%) | |

| Midwife/private service | Yes 102 (92.73%); No 8 (7.27%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Głowińska, A.; Glowinski, S. Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome Among Polish Nurses and Midwives: A Cross-Sectional National Survey. Children 2025, 12, 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091160

Głowińska A, Glowinski S. Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome Among Polish Nurses and Midwives: A Cross-Sectional National Survey. Children. 2025; 12(9):1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091160

Chicago/Turabian StyleGłowińska, Alina, and Sebastian Glowinski. 2025. "Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome Among Polish Nurses and Midwives: A Cross-Sectional National Survey" Children 12, no. 9: 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091160

APA StyleGłowińska, A., & Glowinski, S. (2025). Knowledge of Shaken Baby Syndrome Among Polish Nurses and Midwives: A Cross-Sectional National Survey. Children, 12(9), 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091160