Social Isolation in Turkish Adolescents: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Social Isolation Questionnaire

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.3.1. Information Form

2.3.2. Social Isolation Questionnaire (QIS)

2.3.3. UCLA Loneliness Scale-Short Form (ULS-8)

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Translation

2.4.2. Specialist Opinions

2.4.3. Pilot Test

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Reliability

3.2. Test–Retest Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index |

| ANOVA | One-way Analysis of Variance |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative of Fit Index |

| CVI | Content validity index |

| CVR | Content Validity Ratios |

| DF | Degree of Freedom |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| QIS | Social Isolation Questionnaire |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| ULS-8 | University of California Loneliness Scale-Short Form |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Steinberg, L. Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.B.; McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C. Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1677–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, T.; Danese, A.; Wertz, J.; Ambler, A.; Kelly, M.; Diver, A.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: A longitudinal cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2015, 54, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, M.D.; Cai, T.; Ignatow, G. Social isolation, drunkenness, and cigarette use among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2016, 53, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020, 4, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall-Lande, J.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Christenson, S.L.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence 2007, 42, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.C.; Hinton, E.A.; Gourley, S.L. Persistent behavioral and neurobiological consequences of social isolation during adolescence. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 118, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Hartl, A.C. Understanding loneliness during adolescence: Developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta, D.; Samuel, K. Social Isolation: A Conceptual and Measurement Proposal; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N.; Larsen, P.D. Social Isolation. Lubkin’s Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, VT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, R.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Zhou, X. Social isolation, loneliness, and mobile phone dependence among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Roles of parent–child communication patterns in a sensitive developmental period. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction. 2023, 21, 1931–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, S.J.; Soares, F.C.; Gaoua, N.; Rangel Junior, J.F.; Lima, R.A.; de Barros, M.V.G. Development and validation of a scale to measure social isolation in adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2024, 34, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Social Connection. WHO Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mireku, D.O.; Seidu, A.A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Tachie, S.A.; Dzamesi, P.D. Prevalence and predictors of social isolation among in-school adolescents. North Am. J. Psychol. 2023, 25, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Alsadoun, D.A.; Alotaibi, H.S.; Alanazi, A.I.; Almohsen, L.A.; Almarhoum, N.N.; Mahboub, S. Social isolation among adolescents and its association with depression symptoms. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 52, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Morese, R.; Fabris, M.A. COVID-19 emergency: Social distancing and social exclusion as risks for suicide ideation and attempts in adolescents during a sensitive developmental period. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 551113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, I.L.D.L.; Rego, J.F.; Teixeira, A.C.G.; Moreira, M.R. Social isolation and its impact on child and adolescent development: A systematic review. Rev. Paul Pediatr. 2021, 40, e2020385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, J.; Qualter, P.; Friis, K.; Pedersen, S.S.; Lund, R.; Andersen, C.M.; Bekker-Jeppesen, M.; Lasgaard, M. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspect. Public Health 2021, 141, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Ando, S.; Shimodera, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Usami, S.; Okazaki, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Richards, M.; Hatch, S.; Nishida, A. Preference for solitude, social isolation, suicidal ideation, and self-harm in adolescents. J Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, M.B.M.; Enumo, S.R.F. Reflexões baseadas na Psicologia sobre efeitos da pandemia COVID-19 no desenvolvimento infantil. Estud. Psicol. (Camp.) 2020, 37, e200089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Jose, P.E.; Koyanagi, A.; Meilstrup, C.; Nielsen, L.; Madsen, K.R.; Hinrichsen, C.; Dunbar, R.I.M.; Koushede, V. The moderating role of social network size in the temporal association between formal social participation and mental health: A longitudinal analysis using two consecutive waves of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, S.J.; Hardman, C.M.; Barros, S.S.H.; Santos, C.D.F.B.F.; de Barros, M.V.G. Association between physical activity, participation in Physical Education classes, and social isolation in adolescents. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J.) 2015, 91, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S. The classmates social isolation questionnaire (CSIQ): An initial validation. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Child Behaviour Check-List/4-18 and 1991 Profile; University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Bessaha, M.L.; Sabbath, E.L. The association between social isolation and health: An analysis of parent–adolescent dyads from the family life, activity, sun, health, and eating study. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2020, 48, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M. Youth Problem Inventory; National Psychological Corporation: Agra, India, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Girelli, L.; Lucidi, F.; Manganelli, S.; Alivernini, F. The Classmates Social Isolation Questionnaire for Adolescents (CSIQ-A): Validation and invariance across immigrant background, gender and socioeconomic level. J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 19, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, B.Ç.A. Yalnızlık Ölçeği, Yalnızlık Tercihi Ölçeği ve Sosyal İzolasyon Ölçeği: Geliştirme ve ilk geçerlik çalışmaları. Int. Soc. Ment. Res. Think J. 2021, 7, 665–676. [Google Scholar]

- Küçükdeveci, A.A.; McKenna, S.P.; Kutlay, Ş.; Gürsel, Y.; Whalley, D.; Arasil, T. The development and psychometric assessment of the Turkish version of the Nottingham Health Profile. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2000, 23, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbaşı, A.; Zaganjori, O. Sosyal izolasyonun örgütsel sinizm üzerindeki etkisi. Yönetim. Ekon. Celal Bayar Univ. 2017, 24, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, B.Ç.; Orak, B. COVID-19 Pandemisinin Sağlık Çalışanlarının Finansal Kaygı, İş-Yaşam Dengesi Ve Sosyal İzolasyon Düzeylerine Etkilerinin İncelenmesi. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Bus. 2022, 18, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallengren, E.; Guthold, R.; Newby, H.; Moller, A.B.; Marsh, A.D.; Fagan, L.; Azzopardi, P.; Guèye, M.; Kågesten, A.E. Relevance of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) to adolescent health measurement: A systematic mapping of the SDG Framework and global adolescent health indicators. J. Adolesc. Health. 2024, 74, S47–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health. 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. Ten steps in scale development and reporting: A guide for researchers. Commun. Methods Meas. 2018, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottner, J.; Audigé, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D.L. Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattray, J.; Jones, M.C. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şencan, H. Güvenilirlik ve Geçerlilik; Birinci Baska: Ankara, Turkey, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, W.H. Exploratory Factor Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; p. 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; DiMatteo, M.R. A short-form measure of loneliness. J. Pers. Assess. 1987, 51, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.A.; Duy, B. Adaptation of the short-form of the UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-8) to Turkish for the adolescents. Dusunen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2014, 27, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, F.F.; Meireles, J.F.; Neves, C.M.; Amaral, A.C.; Ferreira, M.E. Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica. 2017, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health. 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapık, C.; Gözüm, S.; Aksayan, S. Intercultural scale adaptation stages, language and culture adaptation: Updated guideline. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 2018, 26, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Kriston, L.; Loh, A.; Spies, C.; Scheibler, F.; Wills, C.; Härter, M. Confirmatory factor analysis and recommendations for improvement of the Autonomy-Preference-Index (API). Health Expect. 2010, 13, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Carlbäck, J. A Study on Factors Influencing Acceptance of Using Mobile Electronic Identification Applications in Sweden. Bachelor’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, M.E.; Smith, G.T. Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayran, M.; Hayran, M. Basic Statistics for Health Research; Art Ofset Matbaacılık Yayıncılık Organizasyon: Ankara, Turkey, 2011; pp. 30–35. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics (M. Baloğlu, Trans.); Nobel Academic Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kartal, M.; Bardakçı, S. Reliability and Validity Analysis with SPSS and AMOS Applied Examples; Akademisyen Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| EFA | CFA | Statistical Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ± SD | ± SD | ||

| Age | 14.04 ± 1.68 | 13.91 ± 1.67 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 468 (48.7) | 482 (50.2) | X2 = 0.408; P = 0.523 |

| Male | 493 (51.3) | 479 (49.8) | ||

| Family type | Nuclear family | 780 (81.2) | 777 (80.9) | X2 = 3.122; P = 0.210 |

| Extended family | 126 (13.1) | 143 (14.9) | ||

| Broken family | 55 (5.7) | 41 (4.3) | ||

| Type of Residence | City center | 743 (77.3) | 765 (79.6) | X2 = 1.825; P = 0.401 |

| District | 134 (13.9) | 115 (12.0) | ||

| Village | 84 (8.7) | 81 (8.4) | ||

| Presence of Siblings | Yes | 890 (92.6) | 880 (91.6) | X2 = 0.714; P = 0.398 |

| No | 71 (7.4) | 81 (8.4) | ||

| Items | ± SD | Corrected Item–Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.35 ± 1.10 | 0.473 | 0.809 |

| 2 | 2.32 ± 1.60 | −0.089 | 0.863 |

| 3 | 0.78 ± 0.76 | 0.513 | 0.809 |

| 4 | 1.17 ± 0.94 | 0.467 | 0.810 |

| 5 | 1.11 ± 0.97 | 0.480 | 0.809 |

| 6 | 0.94 ± 0.92 | 0.460 | 0.810 |

| 7 | 1.49 ± 0.99 | 0.417 | 0.813 |

| 8 | 0.93 ± 0.86 | 0.412 | 0.813 |

| 9 | 1.36 ± 0.81 | 0.510 | 0.809 |

| 10 | 0.71 ± 0.85 | 0.479 | 0.810 |

| 11 | 0.89 ± 0.90 | 0.514 | 0.808 |

| 12 | 1.23 ± 1.04 | 0.370 | 0.816 |

| 13 | 0.84 ± 0.89 | 0.457 | 0.811 |

| 14 | 0.75 ± 0.89 | 0.488 | 0.809 |

| 15 | 0.84 ± 0.85 | 0.624 | 0.802 |

| 16 | 0.70 ± 0.93 | 0.530 | 0.806 |

| 17 | 0.66 ± 0.89 | 0.568 | 0.805 |

| Factors | Items | Factor Loading | λ | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendship | 3 | 0.662 | 4.467 | 19.33% |

| 6 | 0.759 | |||

| 8 | 0.695 | |||

| 10 | 0.740 | |||

| Family Support | 4 | 0.776 | 1.627 | 18.64% |

| 5 | 0.779 | |||

| 7 | 0.739 | |||

| 11 | 0.650 | |||

| Loneliness | 12 | 0.725 | 1.182 | 17.99% |

| 13 | 0.791 | |||

| 14 | 0.557 | |||

| 15 | 0.562 | |||

| 17 | 0.621 | |||

| Total explained variance | 55.97% | |||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficient | 0.860 | |||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 0.000 | |||

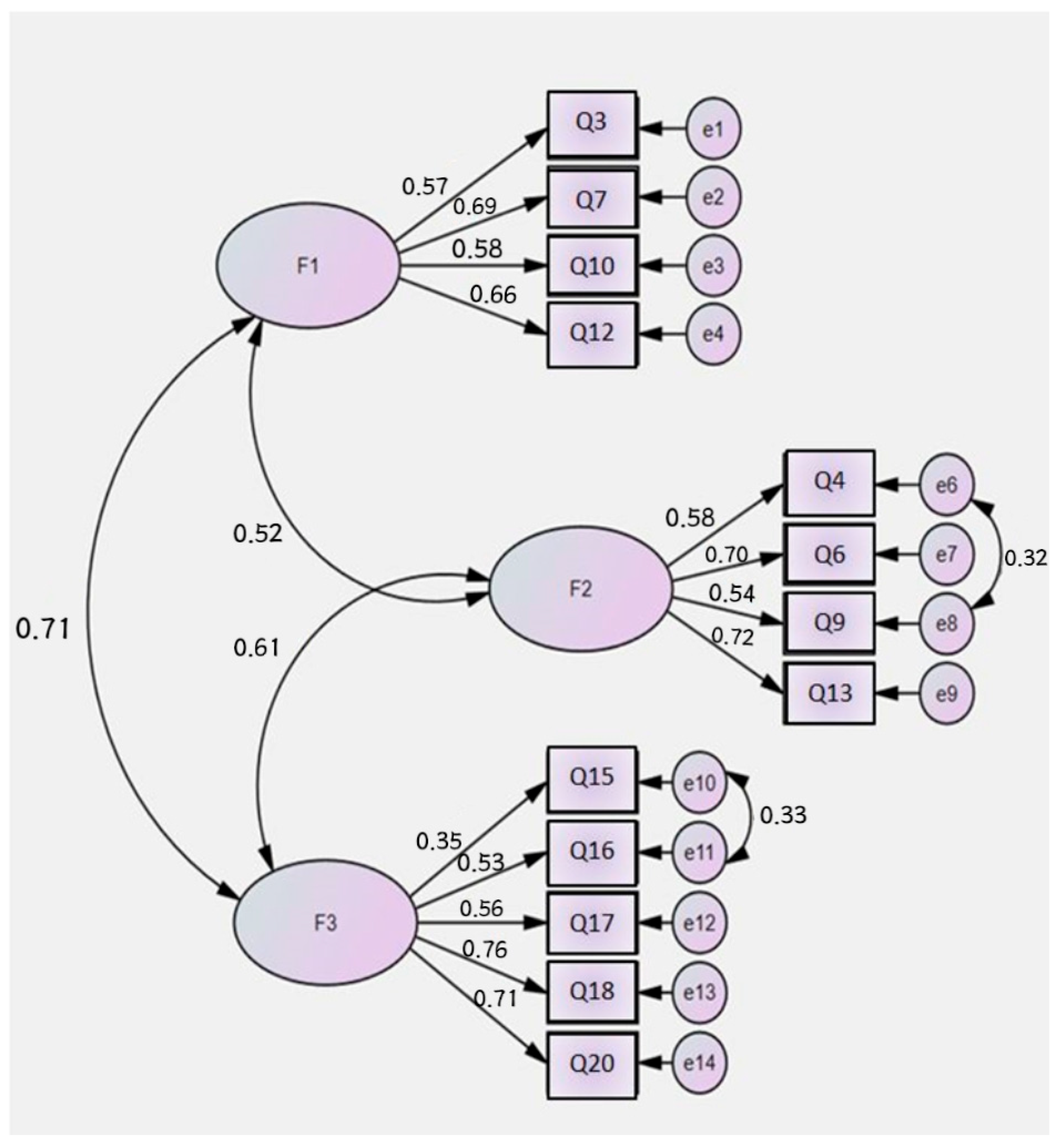

| Scales | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | GFI | AGFI | IFI | TLI | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIS | 3.149 | 0.047 | 0.037 | 0.961 | 0.970 | 0.955 | 0.961 | 0.949 | 0.944 |

| Total Scale Score | Loneliness Subscale | Friendship Subscale | Family Support Subscale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s α | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Cronbach’s α of the first half | 0.68 | |||

| Cronbach’s α of the second half | 0.69 | |||

| Spearman–Brown | 0.87 | |||

| Guttman Split-Half | 0.87 | |||

| Correlation between two halves | 0.78 | |||

| Loneliness | Friendship | Family Support | QIS | ULS-8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | r | 1 | ||||

| p | ||||||

| Friendship | r | 0.543 ** | 1 | |||

| p | 0.000 | |||||

| Family support | r | 0.442 ** | 0.405 ** | 1 | ||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| QIS | r | 0.932 ** | 0.745 ** | 0.664 ** | 1 | |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| ULS-8 | r | 0.537 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.540 ** | 1 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çevik Özdemir, H.N.; Ayran, G. Social Isolation in Turkish Adolescents: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Social Isolation Questionnaire. Children 2025, 12, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091122

Çevik Özdemir HN, Ayran G. Social Isolation in Turkish Adolescents: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Social Isolation Questionnaire. Children. 2025; 12(9):1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091122

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇevik Özdemir, Hamide Nur, and Gülsün Ayran. 2025. "Social Isolation in Turkish Adolescents: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Social Isolation Questionnaire" Children 12, no. 9: 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091122

APA StyleÇevik Özdemir, H. N., & Ayran, G. (2025). Social Isolation in Turkish Adolescents: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Social Isolation Questionnaire. Children, 12(9), 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091122