Parental Perceptions and Actual Oral Health Status of Children in an Italian Paediatric Population in 2024: Findings from an Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Analysed

3.2. Oral Health Conditions

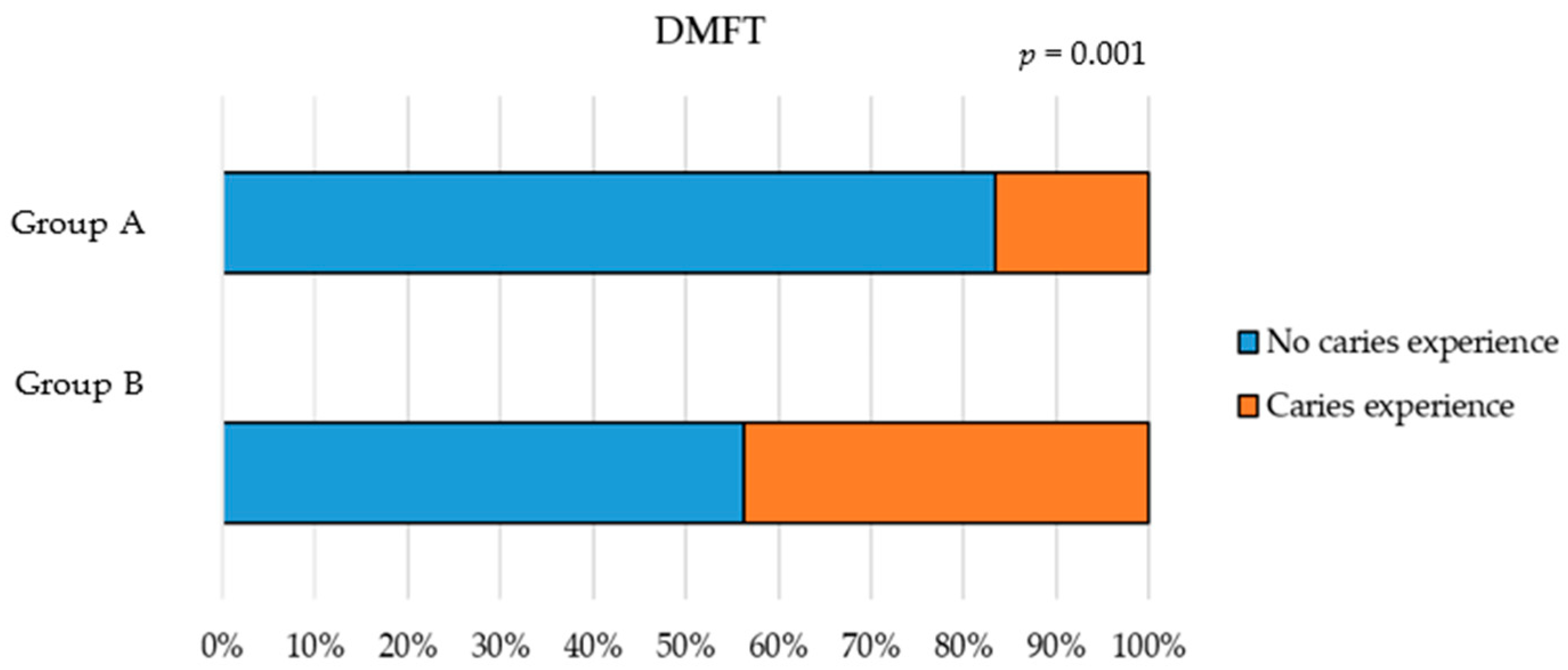

- Caries Experience (dmft/DMFT)

- Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN)

- Gingival Inflammation Status (MGI)

3.3. Supplementary Questions

3.4. Sociodemographic Background

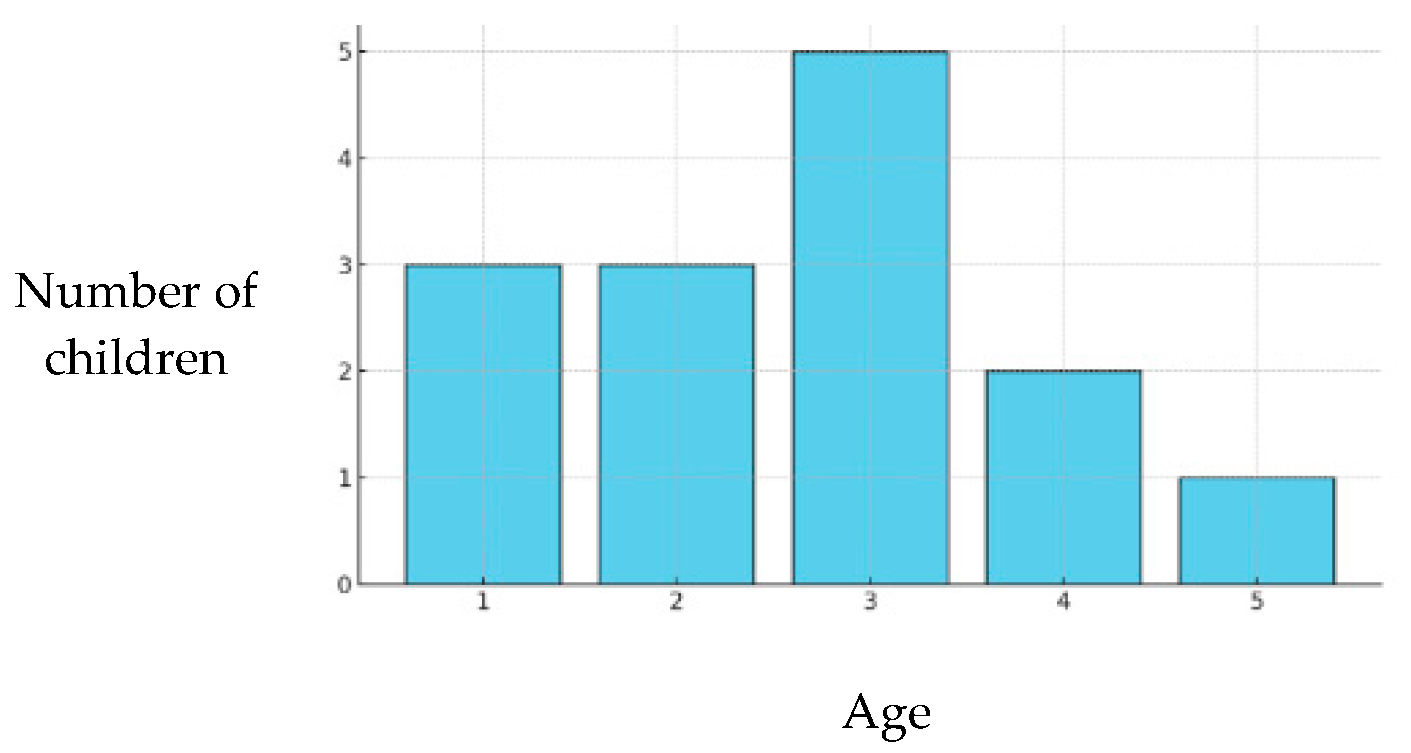

3.5. Age at First Dental Examination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IRCCS G. Gaslini | Istituto di Ricerca e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Giannina Gaslini |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| OHRQoL | Oral Health-Related Quality of Life |

| COHQoL | Child Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life |

| COHIP | Child Oral Health Impact Profile |

| Child-OIDPs | Child Oral Impacts on Daily Performances |

| CPQ | Child Perceptions Questionnaire |

| ECOHIS | Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale |

| PCPQ | Parental–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire |

| FIS | Family Impact Scale |

| DMFT | Decayed (D), Missing (M), and Filled (F) for Permanent Teeth |

| dmft | Decayed (D), Missing (M), and Filled (F) for primary teeth |

| IOTN | Index of Orthodontic treatment Need |

| MGI | Modified Gingival Index |

| EU | European Union |

| years | years |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Oral Health 2023–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, D.; Jokovic, A.; Stephens, M.; Kenny, D.; Tompson, B.; Guyatt, G. Family Impact of Child Oral and Oro-Facial Conditions. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2002, 30, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri, M.F.A.; Jaafari, F.R.M.; Mathmi, N.A.A.; Huraysi, N.H.F.; Nayeem, M.; Jessani, A.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Tadakamadla, J. Impact of the Poor Oral Health Status of Children on Their Families: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2021, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lione, R.; Ralli, M.; De Razza, F.C.; D’Amato, G.; Arcangeli, A.; Carbone, L.; Cozza, P. Oral Health Epidemiological Investigation in an Urban Homeless Population. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health Country Profile: Italy; e: WHO Health Technology Assessment and Health Benefit Package Survey; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Quality of Life Assessment: WHOQOL; Programme on mental health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, W.M.; Foster Page, L.A.; Malden, P.E.; Gaynor, W.N.; Nordin, N. Comparison of the ECOHIS and Short-Form P-CPQ and FIS Scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Foster Page, L.A.; Gaynor, W.N.; Malden, P.E. Short-Form Versions of the Parental-Caregivers Perceptions Questionnaire and the Family Impact Scale. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2013, 41, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, T.; Gómez-Polo, C.; Montero, J.; Curto, D.; Curto, A. An Assessment of Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life and Anxiety in Early Adolescents (11–14 Years) at Their First Dental Visit: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2025, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, B.K.; Bucci, R.; D’Antò, V.; Cascella, S.; Rongo, R.; Valletta, R. Parental Perceptions and Family Impact on Adolescents’ Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Relation to the Severity of Malocclusion and Caries Status. Children 2025, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahel, B.T.; Rozier, R.G.; Slade, G.D. Parental Perceptions of Children’s Oral Health: The Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contaldo, M.; Della Vella, F.; Raimondo, E.; Minervini, G.; Buljubasic, M.; Ogodescu, A.; Sinescu, C.; Serpico, R. Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS): Literature Review and Italian Validation. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Di Blasio, M.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M. Children Oral Health and Parents Education Status: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Zhi, Q.H.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, R.M.; Lin, H.C. Impact of Early Childhood Caries on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Preschool Children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, C.; Campus, G.; Bontà, G.; Vilbi, G.; Conti, G.; Cagetti, M.G. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescent with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Neurotypical Peers: A Nested Case–Control Questionnaire Survey. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 26, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.N.; Moutam, N.; Sowmya, K.; Parvatham, B.B.; Rajesh, D.; Kumar, S. Evaluation of DMFT in School Going Children of Mixed Dentition Stage: An Original Research. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 2847–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P.E.; Baez, R.J.; World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-92-4-154864-9. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.; Palmer, C.E.; Knutson, J.W. Studies on Dental Caries: I. Dental Status and Dental Needs of Elementary School Children. Public Health Rep. (1896–1970) 1938, 53, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, P.H.; Shaw, W.C. The Development of an Index of Orthodontic Treatment Priority. Eur. J. Orthod. 1989, 11, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobene, R.R.; Weatherford, T.; Ross, N.M.; Lamm, R.A.; Menaker, L. A Modified Gingival Index for Use in Clinical Trials. Clin. Prev. Dent. 1986, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, S.; Abdulla, A.M.; Andiesta, N.S.; Babar, M.G.; Pau, A. Role of Family Functioning and Health-Related Quality of Life in Pre-School Children with Dental Caries: A Cross-Sectional Study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Cappai, A.; Castiglia, P.; Campus, G.; Children’s Smiles Sardinian Group. Impact of Socioeconomic Inequalities on Dental Caries Status in Sardinian Children. Children 2024, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theristopoulos, A.; Agouropoulos, A.; Seremidi, K.; Gizani, S.; Papaioannou, W. The Effect of Socio-Economic Status on Children’s Dental Health. Available online: https://www.jocpd.com/articles/10.22514/jocpd.2024.078 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Vallejos, D.; Coll, I.; López-Safont, N. Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2025, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, G.; Solinas, G.; Strohmenger, L.; Cagetti, M.G.; Senna, A.; Minelli, L.; Majori, S.; Montagna, M.T.; Reali, D.; Castiglia, P. National Pathfinder Survey on Children’s Oral Health in Italy: Pattern and Severity of Caries Disease in 4-Year-Olds. Caries Res. 2009, 43, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, G.; Solinas, G.; Cagetti, M.G.; Senna, A.; Minelli, L.; Majori, S.; Montagna, M.T.; Reali, D.; Castiglia, P.; Strohmenger, L. National Pathfinder Survey of 12-Year-Old Children’s Oral Health in Italy. Caries Res. 2007, 41, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Gallus, S.; Beretta, M.; Lugo, A.; Scaglioni, S.; Colombo, P.; Paglia, M.; Gatto, R.; Marzo, G.; Caruso, S.; et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Early Childhood Caries in Italy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, G.; Cocco, F.; Strohmenger, L.; Cagetti, M.G. Caries Severity and Socioeconomic Inequalities in a Nationwide Setting: Data from the Italian National Pathfinder in 12-Years Children. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.K.; Drummond, B.K.; Thomson, W.M. Changes in Aspects of Children’s Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life Following Dental Treatment under General Anaesthesia. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2004, 14, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippaudo, C.; Quinzi, V.; Manai, A.; Paolantonio, E.G.; Valente, F.; La Torre, G.; Marzo, G. Orthodontic Treatment Need and Timing: Assessment of Evolutive Malocclusion Conditions and Associated Risk Factors. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Psychosocial Impact of Oral Conditions during Transition to Secondary Education—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20073542/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Locker, D.; Jokovic, A.; Tompson, B.; Prakash, P. Is the Child Perceptions Questionnaire for 11-14 Year Olds Sensitive to Clinical and Self-Perceived Variations in Orthodontic Status? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute. Italiano Linee Guida Nazionali per La Promozione Della Salute Orale e La Prevenzione Delle Patologie Orali in Età Evolutiva 2014. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/sites/default/files/imported/C_17_pubblicazioni_2073_allegato.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Guideline on Perinatal and Infant Oral Health Care. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 38, 150–154.

| Mother | Father | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Nationality | * | ||

| EU | 116 (88.5) | 114 (88.4) | 230 (88.5) |

| Extra EU | 15 (11.5) | 15 (11.6) | 30 (11.5) |

| Education level | ** | *** | |

| Not going to school | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Primary education | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Middle school | 30 (24.0) | 36 (30.5) | 66 (27.2) |

| Secondary education | 55 (44.0) | 65 (55.1) | 120 (49.4) |

| Postsecondary education | 39 (31.2) | 16 (13.6) | 55 (22.6) |

| Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| ECOHIS0–5 scores | ||

| Total | 4 (1–7) | 5.2 ± 5.6 |

| Child impact | 2 (0–5) | 3.3 ± 4.4 |

| Family impact | 0 (0–3) | 1.9 ± 2.8 |

| 16-PCPQ6–12 scores | ||

| Total | 5 (2–8) | 6.2 ± 7.4 |

| Oral symptoms | 2 (1–5) | 2.9 ± 2.4 |

| Functional limitations | 0 (0–3) | 1.4 ± 2.1 |

| Emotional well-being | 0 (0–2) | 1.3 ± 2.9 |

| Social well-being | 0 (0–0) | 0.6 ± 2.1 |

| FIS6–12 scores | ||

| Total | 5 (1–11) | 6.7 ± 6.6 |

| Parental emotions | 1 (0–3) | 1.7 ± 2.0 |

| Parental family activity | 3 (0–6) | 3.6 ± 3.8 |

| Family conflict | 0 (0–3) | 1.5 ± 1.9 |

| dmft/DMFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Caries Experience | Caries Experience | Total | p | |

| ECOHIS0–5 scores | ||||

| yeTotal | 3.8 ± 3.3 | 12.1 ± 9.9 | 5.2 ± 5.8 | 0.011 |

| Child impact | 2.5 ± 2.9 | 7 ± 7.8 | 3.3 ± 4.4 | 0.102 |

| Family impact | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 5.1 ± 4.1 | 1.9 ± 2.8 | 0.008 |

| 16-PCPQ6–12 scores | ||||

| Total | 5.6 ± 6.1 | 7.0 ± 8.8 | 6.2 ± 7.4 | 0.554 |

| Oral symptoms | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 3 ± 2.4 | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 0.759 |

| Functional limitations | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 0.799 |

| Emotional well-being | 1.0 ± 2.3 | 1.7 ± 3.4 | 1.3 ± 2.9 | 0.444 |

| Social well-being | 0.3 ± 1.2 | 0.9 ± 2.9 | 0.5 ± 2.1 | 0.366 |

| FIS6–12 scores | ||||

| Total | 0.059 | |||

| Parental emotions | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 2.2 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 0.161 |

| Parental family activity | 2.9 ± 3.2 | 4.4 ± 4.4 | 3.6 ± 3.8 | 0.179 |

| Family conflict | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.047 |

| ACI (dmft) | ACI (dmft/DMFT) | ACI (DMFT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 1.1 ± 2.8 | 1.1 ± 2.8 | 0 ± 0 |

| Group B | 1.6 ± 2.9 | 1.9 ± 3.2 | 0.6 ± 1.4 |

| IOTN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Need | Borderline | Need | Total | p | |

| ECOHIS0–5 scores | |||||

| Total | 4.9 ± 5.9 | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 5.3 | 0.213 |

| Child impact | 2.1 ± 3.1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 1.6 ± 2.9 | 0.598 |

| Family impact | 2.8 ± 3.5 | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 3 | 0.247 |

| 16-PCPQ6–12 scores | |||||

| Total | 5.2 ± 7.4 | 6.1 ± 4.1 | 6.3 ± 4.9 | 5.6 ± 6.4 | 0.342 |

| Oral symptoms | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 3.2 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 0.623 |

| Functional limitations | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 1.8 ± 2.5 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 0.851 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.9 ± 2.4 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 2.1 | 0.439 |

| Social well-being | 0.5 ± 2.6 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 2.1 | 0.406 |

| 8-FIS6–12 scores | |||||

| Total | 6.5 ± 5.9 | 10 ± 9.5 | 5.6 ± 4.8 | 6.8 ± 6.4 | 0.562 |

| Parental emotions | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 2.7 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 0.615 |

| Parental family activity | 3.5 ± 3.6 | 4.9 ± 4.9 | 2.9 ± 3.6 | 3.6 ± 3.8 | 0.627 |

| Family conflict | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 0.201 |

| MGI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Gums | Mild Inflammation | Severe Inflammation | Total | p | |

| ECOHIS0–5 scores | |||||

| Total | 4.8 ± 5.1 | 5.5 ± 6.5 | - | 5.2 ± 5.8 | 0.853 |

| Child impact | 3.6 ±3.8 | 3 ± 4.9 | - | 3.3 ± 4.4 | 0.301 |

| Family impact | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 3.2 | - | 1.9 ± 2.8 | 0.246 |

| 16-PCPQ6–12 scores | |||||

| Total | - | 5.6 ± 6.7 | 17.5 ± 11.0 | 6.3 ± 7.4 | 0.004 |

| Oral symptoms | - | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 0.103 |

| Functional limitations | - | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 0.009 |

| Emotional well-being | - | 1.1 ± 2.5 | 5.5 ± 5.2 | 1.3 ± 2.9 | 0.009 |

| Social well-being | - | 0.5 ± 2.0 | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 0.6 ± 2.1 | 0.215 |

| 8-FIS6–12 scores | |||||

| Total | - | 6.5 ± 6.7 | 10.0 ± 3.4 | 6.7 ± 6.6 | 0.123 |

| Parental emotions | - | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 0.095 |

| Parental family activity | - | 3.5 ± 3.9 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 3.8 | 0.383 |

| Family conflict | - | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 2.5 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.255 |

| dmft/DMFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Caries Experience | Caries Experience | Total | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| GROUP A: Oral health parents’ evaluation | 0.008 | |||

| Poor | 1 (2.0) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (6.7) | |

| Below Average | 3 (6.0) | 2 (20.0) | 5 (8.3) | |

| Average | 23 (46.0) | 4 (40.0) | 27 (45.0) | |

| Above Average | 12 (24.0) | 0 | 12 (20.0) | |

| Excellent | 11 (22.0) | 1 (10.0) | 12 (20.0) | |

| Mild Inflammation | Severe Inflammation | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | ||

| Group B: Oral health parents’ evaluation | * | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 4 (6.1) | 4 (100.0) | 8 (11.4) | |

| Below Average | 7 (10.6) | 0 | 7 (10.0) | |

| Average | 45 (68.2) | 0 | 45 (64.3) | |

| Above Average | 6 (9.1) | 0 | 6 (8.6) | |

| Excellent | 4(6.1) | 0 | 4 (5.7) |

| dmft/DMFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Caries Experience | Caries Experience | Total | ||

| Group A: Nationality | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p |

| Mother | 0.021 | |||

| EU | 46 (92.0) | 6 (60.0) | 52 (86.7) | |

| Extra EU | 4 (8.0) | 4 (40.0) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Father * | 0.014 | |||

| EU | 43 (87.9) | 5 (50.0) | 48 (81.4) | |

| Extra EU | 6 (12.2) | 5 (50.0) | 11 (18.6) | |

| dmft/DMFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Caries Experience | Caries Experience | Total | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| Group B: Mother’s education | * | 0.036 | ||

| None or Primary school | 0 | 1 (3.5) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Middle school | 5 (12.8) | 11 (37.9) | 16 (23.5) | |

| High School | 20 (51.3) | 11 (37.9) | 31 (45.6) | |

| Degree | 14 (35.9) | 6 (20.7) | 20 (29.4) | |

| MGI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Inflammation | Severe Inflammation | Total | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| Group B: Father’s education | * | 0.041 | ||

| Primary school | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | |

| Middle school | 17 (28.3) | 4 (100.0) | 21 (32.8) | |

| High School | 33 (55.0) | 0 | 33 (51.6) | |

| Degree | 9 (19.0) | 0 | 9 (14.1) | |

| Age | No Caries Experience | Caries Experience | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Median (IQR) Mean ± SD | 2 (1.0–3.0) 2.1 ± 1.3 | 3.5 (3–5) 3.8 ± 1.5 | 0.002 0.002 |

| Group B | Median (IQR) Mean ± SD | 5 (4.0–6.0) 5.2 ± 2.0 | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) 6.3 ± 2.2 | 0.013 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Capurro, C.; Romanelli, G.; Telini, G.; Casali, V.; Calevo, M.G.; Fragola, M.; Laffi, N. Parental Perceptions and Actual Oral Health Status of Children in an Italian Paediatric Population in 2024: Findings from an Observational Study. Children 2025, 12, 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091119

Capurro C, Romanelli G, Telini G, Casali V, Calevo MG, Fragola M, Laffi N. Parental Perceptions and Actual Oral Health Status of Children in an Italian Paediatric Population in 2024: Findings from an Observational Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091119

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapurro, Claudia, Giulia Romanelli, Giulia Telini, Virginia Casali, Maria Grazia Calevo, Martina Fragola, and Nicola Laffi. 2025. "Parental Perceptions and Actual Oral Health Status of Children in an Italian Paediatric Population in 2024: Findings from an Observational Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091119

APA StyleCapurro, C., Romanelli, G., Telini, G., Casali, V., Calevo, M. G., Fragola, M., & Laffi, N. (2025). Parental Perceptions and Actual Oral Health Status of Children in an Italian Paediatric Population in 2024: Findings from an Observational Study. Children, 12(9), 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091119