The Arabic Version Validation of the Social Worries Questionnaire for Preadolescent Children

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

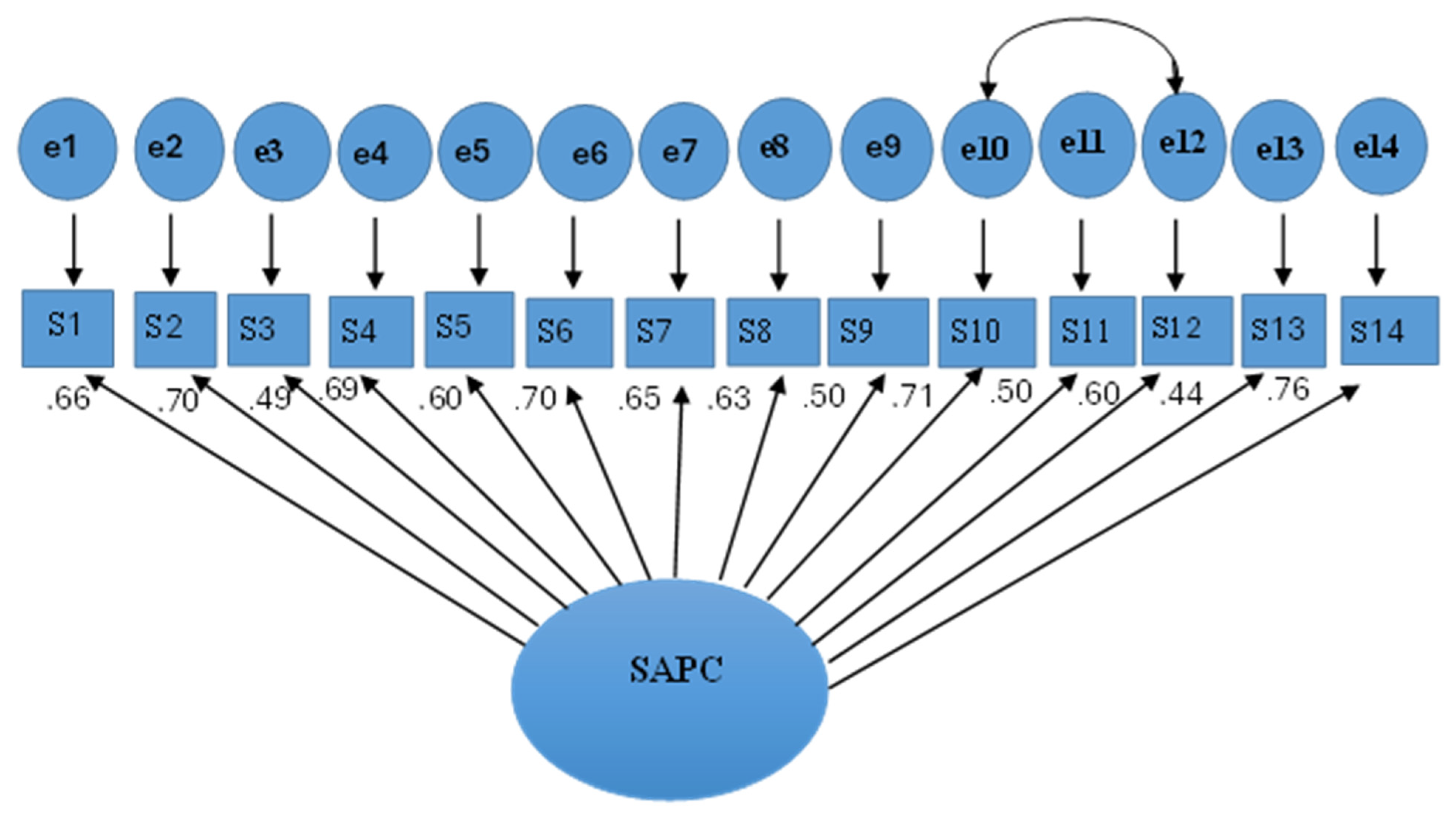

3.2. Validity

3.3. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldahadha, B.; Al-Bahran, M. Academic Advising Services among Sultan Qaboos University and University of Nizwa students in light of Some Variables. Int. J. Res. Educ. 2012, 32, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, E.; Clark, D.M. Understanding Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescents and Improving Treatment Outcomes: Applying the Cognitive Model of Clark and Wells (1995). Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. review 2018, 21, 388–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahadha, B. Self-disclosure, mindfulness, and their relationships with happiness and well-being. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Figueiredo, D.V.; Vagos, P. The Prevalence of Adolescent Social Fears and Social Anxiety Disorder in School Contexts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aldahadha, B. The Effectiveness of Training on Time Management Skill Due to Relaxation Techniques upon Stress and Achievement among Mutah University Students. Br. J. Psychol. Res. 2017, 6, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, C. Tratamiento de un joven con ansiedad social. In Tratamiento paso a paso de los Problemas Psicológicos en la Infancia y la Adolescencia; Orgilés, M., Méndez, F.X., Espada, J.P., Eds.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Amorós-Reche, V.; Pineda, D.; Orgilés Spanish, J. Adaptation of the Social Worries Questionnaire (SWQ): A Tool to Assess Social Anxiety in Preadolescent Children. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2024, 42, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, C.L.; Westenberg, P.M.; Oosterlaan, J.; Heyne, D.A. Changes in social fears across childhood and adolescence: Age-related differences in the factor structure of the Fear Survey Schedule for Children-Revised. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canals, J.; Voltas, N.; Hernández-Martínez, C.; Cosi, S.; Arija, V. Prevalence of DSM-5 anxiety disorders, comorbidity, and persistence of symptoms in Spanish early adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Méndez, X.; Espada, J.P.; Carballo, J.L.; Piqueras, J.A. Anxiety disorder symptoms in children and adolescents: Differences by age and gender in a community sample. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2012, 5, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Urzúa, A.; Villalonga-Olives, E.; Atencio-Quevedo, D.; Irarrázaval, M.; Flores, J.; Ramírez, C. Children’s mental health: Discrepancy between child self-reporting and parental reporting. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Los Reyes, A.; Augenstein, T.M.; Wang, M.; Thomas, S.A.; Drabick, D.A.G.; Burgers, D.E.; Rabinowitz, J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 858–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conijn, J.M.; Smits, N.; Hartman, E.E. Determining at What Age Children Provide Sound Self-Reports: An Illustration of the Validity-Index Approach. Assessment 2020, 27, 1604–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, E.D. Improving data quality when surveying children and adolescents: Cognitive and social development and its role in questionnaire construction and pretesting. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Finland: Research Programs, Public Health Challenges and Health and Welfare of Children and Young People, Naantali, Finland, 10–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tulbure, B.T.; Szentagotai, A.; Dobrean, A.; David, D. Evidence-based clinical assessment of child and adolescent social phobia: A critical review of rating scales. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Spence, S.H.; Hesse, J.; Shakir, A.; Creswell, C. Identifying children with anxiety disorders using brief versions of the Spence Children’s anxiety scale for children, parents, and teachers. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 1342–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidel, D.C.; Turner, S.M.; Morris, T.L. A new inventory to assess childhood social anxiety and phobia: The social phobia and anxiety inventory for children. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballo, V.E.; Arias, B.; Salazar, I.C.; Calderero, M.; Irurtia, M.J.; Ollendick, T.H. A new selfreport assessment measure of social phobia/anxiety in children: The social anxiety questionnaire for children (SAQ-C24). Behav. Psychol. 2012, 20, 485–503. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-34357-001 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Masia-Warner, C.; Storch, E.A.; Pincus, D.B.; Klein, R.G.; Heimberg, R.G.; Liebowitz, M.R. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and adolescents: An initial psychometric investigation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, J.; Sánchez-García, R.; López-Pina, J.A.; Rosa-Alcázar, A.I. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia and anxiety inventory for children in a Spanish sample. Span. J. Psychol. 2010, 13, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.H. Social Skills Training: Enhancing Social Competence with Children and Adolescents. Research and Technical Supplement 1995a NFER-NELSON. Available online: https://www.scaswebsite.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SST-supplement-low.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Spence, S.H. Social Worries Questionnaire—Pupil 1995b, NFER-NELSON. Available online: https://www.scaswebsite.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Social-Worries-Q-Youth.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- La Greca, A.M.; Stone, W.L. Social Anxiety Scale for Children—Revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1993, 22, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözpınar, N.; Cakiroglu, S.; Zorlu, A.; Yıldırım Budak, B.; Görmez, V. Videoconference anxiety: Conceptualization, scale development, and preliminary validation. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2022, 86, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martínez, I.; Morales, A.; Méndez, F.X.; Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M. Spanish adaptation and psychometric properties of the parent version of the short Mood and feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ-P) in a nonclinical sample of young school-aged children. Span. J. Psychol. 2020, 23, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Menchón, M.; Orgilés, M.; Espada, J.P.; Morales, A. Validation of the brief version of the Spence Children’s anxiety scale for Spanish children (SCAS-C-8). J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.; Brechman-Toussaint, M. The treatment of childhood social phobia: The effectiveness of a social skills training-based, cognitive-behavioral intervention, with and without parental involvement. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2000, 41, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxford, S.; Hadwin, J.A.; Kovshoff, H. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a School-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Intervention for Anxiety in Adolescents Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3896–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.W.; Maddox, B.B.; Panneton, R.K. Fear of negative evaluation influences eye gaze in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3446–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bana, M.; Al-Shoja, Y.; Al-Batool, I. Standardization of the Spence Child Anxiety Scale (SCAS) Among Preschool Children in Ibb Governorate, Republic of Yemen. 2020, pp. 1–46. Available online: https://search.shamaa.org/fullrecord?ID=335538 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Dabbous, M.; Hallit, R.; Malaeb, D.; Sawma, T.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Development and validation of a shortened version of the Child Abuse Self Report Scale (CASRS-12) in the Arabic language. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, G.A.; Beshai, J.A. Arabic version of the Children’s Depression Inventory: Reliability and validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1989, 18, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, D.; Martín-Vivar, M.; Sandín, B.; Piqueras, J.A. Factorial invariance and norms of the 30-item shortened-version of the revised child anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS-30). Psicothema 2018, 30, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.É.; Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Stage, F.K.; King, J.; Nora, A.; Barlow, E.A. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 15th ed.; Taylor Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Halldorsson, B.; Waite, P.; Harvey, K.; Pearcey, S.; Creswell, C. In the moment social experiences and perceptions of children with social anxiety disorder: A qualitative study. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 62, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; Bernstein, E.E.; McNally, R.J. Bridging maladaptive social self-beliefs and social anxiety: A network perspective. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygsman, A.; Vaillancourt, T. Elevated social anxiety symptoms across childhood and adolescence predict adult mental disorders and cannabis use. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 115, e152302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, E.E.; Young, J.F.; Hankin, B.L. Temporal dynamics and longitudinal co-occurrence of depression and different anxiety syndromes in youth: Evidence for reciprocal patterns in a 3-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 10 de Octubre. día Mundial de la Salud Mental. la Urgencia de un Compromiso Conjunto con la Salud Mental y el Bienestar Emocional de niños, niñas y Adolescents 2022, UNICEF Spain. Available online: https://www.unicef.es/sites/unicef.es/files/communication/D%C3%ADa_Mundial_Salud_Mental_octubre_2022.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Aldahadha, B.; Melhem, A.; Al-Hawari, L. Irrational Beliefs Inventory among the Convicted Terrorists Believing Extremists Prisoners in Jordan and Coping Strategies. Dirasat Hum. Soc. Sci. 2019, 46, 117–132. Available online: https://archives.ju.edu.jo/index.php/hum/article/view/15760 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

| Characteristics | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Child’s age | |

| 8 | 14.50% (39) |

| 9 | 19.70% (53) |

| 10 | 20.44% (55) |

| 11 | 18.22% (49) |

| 12 | 27.14% (73) |

| The highest qualification of both parents or one of them | |

| Diploma and below | 47.21% (127) |

| Bachelor | 29.37% (79) |

| Master and above | 23.42% (63) |

| Parent’s marital status | |

| Married and living together | 78.81% (212) |

| Divorced or separated | 10.41% (28) |

| Single | 10.78% (29) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 25.28% (68) |

| Medium | 48.33% (130) |

| High | 26.39% (71) |

| Order of birth | |

| First | 31.23% (84) |

| Mid | 46.46% (125) |

| last | 22.31% (60) |

| Family size | |

| 3 and below | 24.16% (65) |

| 4–6 | 53.53% (144) |

| 7 and above | 22.31% (60) |

| Items | Items (Arabic) | M (SD) | ρi-t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Going to parties | الذهاب إلى الحفلات | 0.40 (0.78) | 0.55 |

| 2. | Using the telephone | استخدام الهاتف | 0.48 (0.64) | 0.53 |

| 3. | Meeting new people | التعرف على أشخاص جدد | 0.52 (0.82) | 0.58 |

| 4. | Presenting work to the class | تقديم العروض في الصف | 0.48 (0.50) | 0.44 |

| 5. | Attending clubs or sports activities | حضور النوادي أو الأنشطة الرياضية | 0.75 (0.69) | 0.58 |

| 6. | Asking a group of kids if I can join in | سؤال مجموعة من الأطفال عما إذا كان بإمكاني الانضمام | 0.59 (0.77) | 0.64 |

| 7. | Talking in front of a group of adults | التحدث أمام مجموعة من البالغين | 0.73 (0.82) | 0.50 |

| 8. | Going shopping alone | الذهاب للتسوق بمفردي | 0.76 (0.89) | 0.60 |

| 9. | Standing up for myself with other kids | الدفاع عن نفسي مع الأطفال الآخرين | 0.80 (0.74) | 0.46 |

| 10. | Entering a room full of people | دخول غرفة مكتظة بالناس | 0.74 (0.63) | 0.53 |

| 11. | Using public toilets or bathrooms | استخدام المراحيض العامة أو الحمامات | 0.38 (0.79) | 0.58 |

| 12. | Eating in public | تناول الطعام في الأماكن العامة | 0.48 (0.89) | 0.53 |

| 13. | Taking tests at school | إجراء الاختبارات في المدرسة | 0.75 (0.75) | 0.54 |

| 14. | Talking in a video call | التحدث في مكالمة فيديو | 0.39 (0.67) | 0.59 |

| Model | df; χ2 | p | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | GFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77; 153.12 | 0.004 | 0.068 | 0.093 | 0.970 | 0.986 |

| 2 | 72; 104.67 | 0.002 | 0.052 | 0.089 | 0.943 | 0.938 |

| AVCDI | SCAS | CASRS-12 | PSA | PHA | SEA | NEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| (p) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saraireh, A.; Aldahadha, B. The Arabic Version Validation of the Social Worries Questionnaire for Preadolescent Children. Children 2025, 12, 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080994

Saraireh A, Aldahadha B. The Arabic Version Validation of the Social Worries Questionnaire for Preadolescent Children. Children. 2025; 12(8):994. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080994

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaraireh, Asma, and Basim Aldahadha. 2025. "The Arabic Version Validation of the Social Worries Questionnaire for Preadolescent Children" Children 12, no. 8: 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080994

APA StyleSaraireh, A., & Aldahadha, B. (2025). The Arabic Version Validation of the Social Worries Questionnaire for Preadolescent Children. Children, 12(8), 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080994