Nurse-Initiated Improvement for Documentation of Penicillin Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatric Urgent Care Clinics

Abstract

Highlights

- Nurse-initiated interventions improved penicillin allergy label documentation.

- Improved documentation of reactions did not increase triage time.

- Nurse engagement in initiatives can offer new perspectives and contribute to success

- Future efforts may focus on engaging families in penicillin allergy discussions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

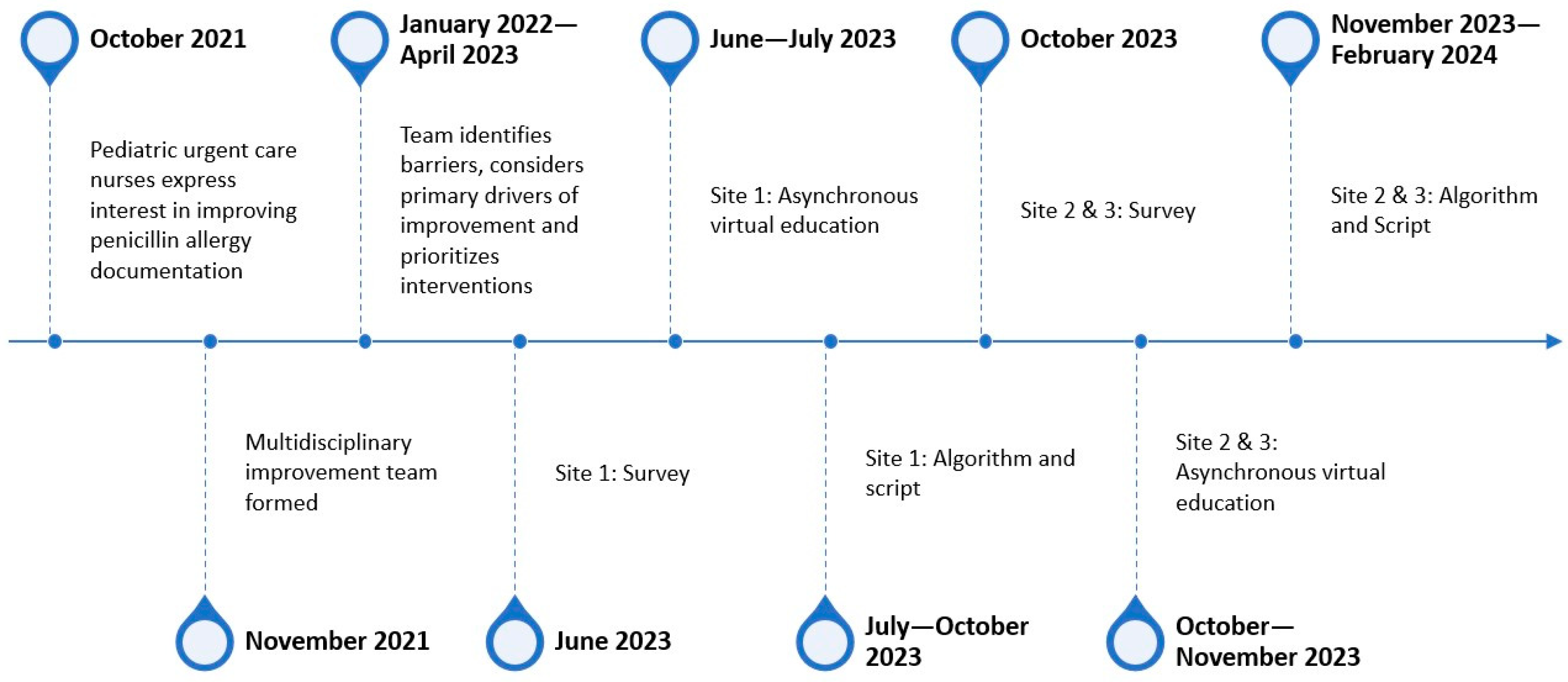

2. Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Interventions

2.3. Study of the Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

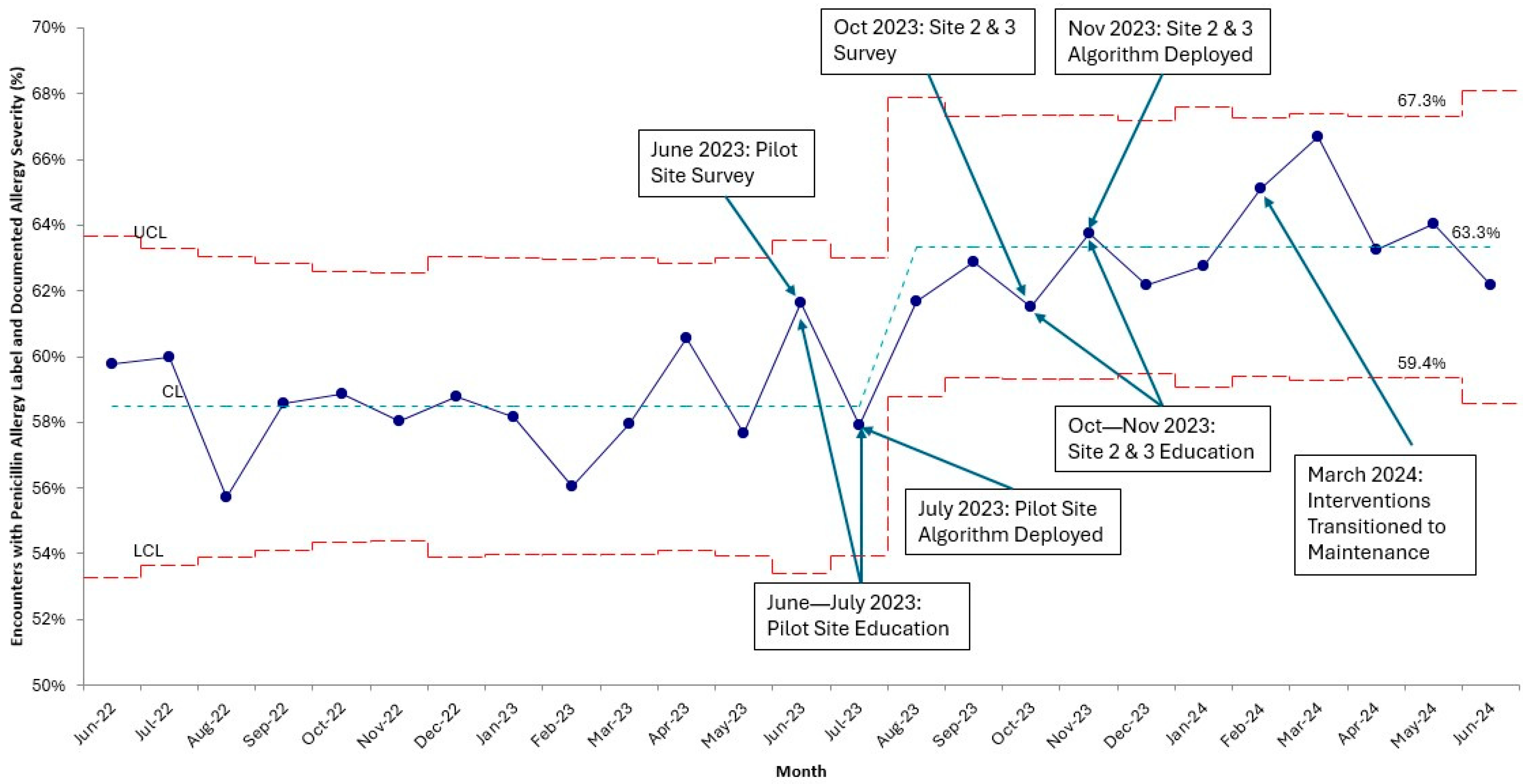

3.2. Primary Outcome and Balancing Measure

3.3. Process Measure

3.4. Survey

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macy, E. Penicillin and beta-lactam allergy: Epidemiology and diagnosis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dhopeshwarkar, N.; Blumenthal, K.G.; Goss, F.; Topaz, M.; Slight, S.P.; Bates, D.W. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy 2016, 71, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.G.; Joerger, T.; Li, Y.; Scheurer, M.E.; Russo, M.E.; Gerber, J.S.; Palazzi, D.L. Factors Associated With Penicillin Allergy Labels in Electronic Health Records of Children in 2 Large US Pediatric Primary Care Networks. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e222117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, A.E.; Konvinse, K.; Phillips, E.J.; Broyles, A.D. Antibiotic Allergy in Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20172497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A.L.; Shapiro, D.J.; Zhang, M.; Madaras-Kelly, K. Contribution of Penicillin Allergy Labels to Second-Line Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Prescribing for Pediatric Respiratory Tract Infections. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2020, 9, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffres, M.N.; Narayanan, P.P.; Shuster, J.E.; Schramm, G.E. Consequences of avoiding β-lactams in patients with β-lactam allergies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Sandoe, J.A.T. A rapid literature review of the impact of penicillin allergy on antibiotic resistance. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Abbo, L.M.; MacDougall, C.; Schuetz, A.N.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Dellit, T.H.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Fishman, N.O.; et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e51–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bediako, H.; Dutcher, L.; Rao, A.; Sigafus, K.; Harker, C.; Hamilton, K.W.; Fadugba, O. Impact of an inpatient nurse-initiated penicillin allergy delabeling questionnaire. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.A.; Wrenn, R.; Sarubbi, C.; Kleris, R.; Lugar, P.L.; Radojicic, C.; Moehring, R.W.; Anderson, D.J. Evaluation of a Pharmacist-Led Penicillin Allergy Assessment Program and Allergy Delabeling in a Tertiary Care Hospital. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e219820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, L.L.; DeBoy, J.T.; Gunaratne, A.; Stallings, A.P.; Bell, T.; Phillips, M.A.; Kamath, S.S.; Sterrett, E.C.; Nazareth-Pidgeon, K.M. Improving the Documentation of Penicillin Allergy Labels Among Pediatric Inpatients. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.G.; Joerger, T.; Anvari, S.; Li, Y.; Gerber, J.S.; Palazzi, D.L. The Quality and Management of Penicillin Allergy Labels in Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022059309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, W.J.; Patel, S.; Lee, E.J.; Finch, N.A.; Su, C.P.; Teran, N.A.; Huang, Y.H.; Shehadeh, F.; Alsafadi, M.Y. Implementation and performance of a nurse administered modified PEN-FAST clinical decision rule in the electronic health record. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2025, 5, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, L.M.; Murray, S.K. The Health Care Data Guide: Learning from Data for Improvement; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Monsees, E.; Popejoy, L.; Jackson, M.A.; Lee, B.; Goldman, J. Integrating staff nurses in antibiotic stewardship: Opportunities and barriers. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, M.; Heard, K.L.; May, A.; Pilgrim, R.; Sandoe, J.; Tansley, S.; Scott, J. Health outcomes of penicillin allergy testing in children: A systematic review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.J.; Greendyke, W.G.; Furuya, E.Y.; Srinivasan, A.; Shelley, A.N.; Bothra, A.; Saiman, L.; Larson, E.L. Exploring the nurses’ role in antibiotic stewardship: A multisite qualitative study of nurses and infection preventionists. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsees, E.; Manning, M.L.; El Feghaly, R.; Carter, E.; Hwang, S.; Schmidt, T.; O’Callahan, C.; Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M. (Eds.) Parental Perceptions of Penicillin Allergy Labels: Findings from a Multisite Survey at Two Pediatric Primary Locations. In Proceedings of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Spring Conference, ChampionsGate, FL, USA, 27–30 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Antoon, J.W.; Grijalva, C.G.; Carroll, A.R.; Johnson, J.; Stassun, J.; Bonnet, K.; Schlundt, D.G.; Williams, D.J. Parental Perceptions of Penicillin Allergy Risk Stratification and Delabeling. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, L.L.; DeBoy, J.T.; Hornik, C.P.; White, M.J.; Nazareth-Pidgeon, K.M. Association of Sociodemographic Factors With Reported Penicillin Allergy in Pediatric Inpatients. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, Z.; Lee, B.R.; Nedved, A.; McKinsey, J.; Turcotte Benedict, F.; Missel, B.; Pandya, A.; El Feghaly, R.E. Pediatric penicillin allergy labels: Influence of race, insurance, and Area Deprivation Index. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mutakabbir, J.C.; Tan, K.K.; Johnson, C.L.; McGrath, C.L.; Zerr, D.M.; Marcelin, J.R. Prioritizing Equity in Antimicrobial Stewardship Efforts (EASE): A framework for infectious diseases clinicians. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2024, 4, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olans, R.N.; Olans, R.D.; DeMaria, A., Jr. The Critical Role of the Staff Nurse in Antimicrobial Stewardship—Unrecognized, but Already There. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, M.L.; Septimus, E.J.; Ashley, E.S.D.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Fakih, M.G.; Schweon, S.J.; Myers, F.E.; Moody, J.A. Antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention-leveraging the synergy: A position paper update. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2018, 46, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsees, E.; Lee, B.; Wirtz, A.; Goldman, J. Implementation of a Nurse-Driven Antibiotic Engagement Tool in 3 Hospitals. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsees, E.A.; Tamma, P.D.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Miller, M.A.; Fabre, V. Integrating bedside nurses into antibiotic stewardship: A practical approach. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman Johnson, C.; Ridge, L.J.; Hessels, A.J. Nurse Engagement in Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Healthc. Qual. 2023, 45, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Vaillancourt, R.; Bair, L.; Wong, E.; King, J.W. Accuracy of Adverse Drug Reaction Documentation upon Implementation of an Ambulatory Electronic Health Record System. Drugs Real. World Outcomes 2016, 3, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, A.F.; Abdul-Massih, S.; Stevenson, J.M.; Alvarez-Arango, S. Use of the Electronic Health Record for Monitoring Adverse Drug Reactions. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023, 23, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall | Baseline Period | Intervention Period | Post-Intervention Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Encounters | 14,084 | 6760 | 5090 | 2234 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 257 (1.8) | 111 (1.6) | 98 (1.9) | 48 (2.1) |

| Black | 1096 (7.8) | 516 (7.6) | 399 (7.8) | 181 (8.1) |

| Hispanic | 2003 (14.2) | 970 (14.3) | 718 (14.1) | 315 (14.1) |

| Multiracial | 651 (4.6) | 329 (4.9) | 239 (4.7) | 83 (3.7) |

| White | 9724 (69.0) | 4652 (68.8) | 3517 (69.1) | 1555 (69.6) |

| Other | 243 (1.7) | 118 (1.7) | 88 (1.7) | 37 (1.7) |

| Unknown/Declined | 110 (0.8) | 64 (0.9) | 31 (0.6) | 15 (0.7) |

| Insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Commercial | 7674 (54.5) | 3622 (53.6) | 2837 (55.7) | 1215 (54.4) |

| Medicaid | 5527 (39.2) | 2776 (41.1) | 1920 (37.7) | 831 (37.2) |

| Self-pay | 438 (3.1) | 150 (2.2) | 177 (3.5) | 111 (5.0) |

| Other/Unknown | 445 (3.2) | 212 (3.1) | 156 (3.1) | 77 (3.4) |

| Language, n (%) | ||||

| English | 13,678 (97.1) | 6560 (97.0) | 4953 (97.3) | 2165 (96.9) |

| Spanish | 295 (2.1) | 139 (2.1) | 106 (2.1) | 50 (2.2) |

| Other | 111 (0.8) | 61 (0.9) | 31 (0.6) | 19 (0.9) |

| Baseline Period N = 6760 | Intervention Period N = 5090 | Post-Intervention Period N = 2234 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Documented | Unknown | p Value | Documented | Unknown | p Value | Documented | Unknown | p Value | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.349 | ||||||

| Asian | 57 (1.4) | 54 (2.0) | 47 (1.4) | 51 (2.8) | 28 (1.9) | 20 (2.7) | |||

| Black | 301 (7.3) | 215 (8.1) | 246 (7.5) | 153 (8.4) | 110 (7.4) | 71 (9.4) | |||

| Hispanic | 594 (14.5) | 376 (14.2) | 468 (14.3) | 250 (13.7) | 216 (14.6) | 99 (13.2) | |||

| Multiracial | 179 (4.4) | 150 (5.6) | 178 (5.4) | 61 (3.4) | 59 (4.0) | 24 (3.2) | |||

| White | 2845 (69.3) | 1807 (68.0) | 2252 (68.9) | 1265 (69.5) | 1032 (69.6) | 523 (69.5) | |||

| Other | 83 (2.0) | 35 (1.3) | 61 (1.9) | 27 (1.5) | 25 (1.7) | 12 (1.6) | |||

| Unknown/Declined | 45 (1.1) | 19 (0.7) | 18 (0.6) | 13 (0.7) | 12 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) | |||

| Insurance, n (%) | 0.037 | 0.599 | 0.830 | ||||||

| Commercial | 2207 (53.8) | 1415 (53.3) | 1812 (55.4) | 1025 (56.3) | 811 (54.7) | 404 (53.7) | |||

| Medicaid | 1692 (41.2) | 1084 (40.8) | 1250 (38.2) | 670 (36.8) | 552 (37.2) | 279 (37.1) | |||

| Self-pay | 96 (2.3) | 54 (2.0) | 114 (3.5) | 63 (3.5) | 70 (4.7) | 41 (5.5) | |||

| Other/Unknown | 109 (2.7) | 103 (3.9) | 94 (2.9) | 62 (3.4) | 49 (3.3) | 28 (3.7) | |||

| Language, n (%) | 0.616 | 0.769 | 0.033 | ||||||

| English | 3977 (96.9) | 2583 (97.3) | 3178 (97.2) | 1775 (97.5) | 1427 (96.3) | 738 (98.1) | |||

| Spanish | 90 (2.2) | 49 (1.8) | 71 (2.2) | 35 (1.9) | 38 (2.6) | 12 (1.6) | |||

| Other | 37 (0.9) | 24 (0.9) | 21 (0.6) | 10 (0.5) | 17 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) | |||

| Prescribers (n = 40) | Nurses (n = 47) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Urgent Care Clinic, n (%) | ||

| A | 13 (32.5) | 14 (29.8) |

| B | 11 (27.5) | 11 (23.4) |

| C | 14 (35.0) | 22 (46.8) |

| Missing | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Time since last clinical degree, n (%) | ||

| <1 year | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) |

| 1–5 years | 5 (12.5) | 8 (17.4) |

| 6–10 years | 10 (25.0) | 10 (21.7) |

| 11–15 years | 9 (22.5) | 7 (15.2) |

| >15 years | 16 (40.0) | 20 (43.5) |

| Worked at institution, n (%) | ||

| <5 years | 9 (22.5) | 10 (21.7) |

| 5–10 years | 10 (25.0) | 12 (26.1) |

| 11–15 | 7 (17.5) | 3 (6.5) |

| >15 years | 14 (35.0) | 21 (45.6) |

| Prescribers (n = 40) | Nurses (n = 47) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents | Median Level of Agreement [IQR] | Respondents | Median Level of Agreement [IQR] | p Value | |

| I am confident in my ability to identify delayed reactions to antibiotics based on timing of symptoms after ingestion of the antibiotic. | 40 | 4 [3, 4] | 46 | 3 [3, 4] | 0.416 |

| Many patients who think they are allergic to penicillin can safely take penicillin. | 39 | 5 [4, 5] | 46 | 4 [4, 4] | 0.003 |

| I am knowledgeable about the risks of avoiding penicillin in patients that have a documented penicillin allergy. | 39 | 4 [4, 5] | 45 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.056 |

| I can distinguish between common pediatric conditions that are often misinterpreted as a penicillin allergy (i.e., viral rash, vomiting/diarrhea). | 40 | 4 [3, 4] | 47 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.880 |

| I am aware that penicillin allergy sensitivities can change over time. | 40 | 4 [3.75, 4] | 47 | 4 [4, 4.5] | 0.160 |

| I am able to identify factors associated with true allergic reactions. | 40 | 4 [4, 4] | 45 | 4 [4, 4] | 0.980 |

| I am aware of the types of penicillin allergy challenges that [our institution] offers. | 40 | 3 [2, 4] | 45 | 3 [2, 4] | 0.987 |

| I feel confident in my ability to appropriately document an adverse drug reaction in the electronic health record, even when a family describes side effects. | 40 | 4 [3, 4] | 46 | 4 [3.25, 5] | 0.010 |

| My documentation of adverse drug reactions influences future antibiotic prescribing. | 40 | 4 [4, 5] | 44 | 4 [4, 5] | 0.356 |

| Time pressures (e.g., patient flow) influence my ability to reconcile between allergy and side effect. | 39 | 4 [3, 4] | 45 | 3 [2, 4] | 0.001 |

| Perceived parent expectations influence my ability to reconcile between allergy and side effects. | 40 | 4 [3.75, 4] | 44 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.529 |

| I feel confident continuing to administer or prescribe an antibiotic in the setting of a reported adverse drug reaction. | 40 | 3 [2, 4] | 44 | 3 [2, 4] | 0.409 |

| I feel confident in my ability to talk with families about antibiotic side effects and reactions. | 40 | 4 [3, 4] | 46 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monsees, E.; Petrie, D.; El Feghaly, R.E.; Suppes, S.; Lee, B.R.; Whitt, M.; Nedved, A. Nurse-Initiated Improvement for Documentation of Penicillin Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatric Urgent Care Clinics. Children 2025, 12, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081087

Monsees E, Petrie D, El Feghaly RE, Suppes S, Lee BR, Whitt M, Nedved A. Nurse-Initiated Improvement for Documentation of Penicillin Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatric Urgent Care Clinics. Children. 2025; 12(8):1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081087

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonsees, Elizabeth, Diane Petrie, Rana E. El Feghaly, Sarah Suppes, Brian R. Lee, Megan Whitt, and Amanda Nedved. 2025. "Nurse-Initiated Improvement for Documentation of Penicillin Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatric Urgent Care Clinics" Children 12, no. 8: 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081087

APA StyleMonsees, E., Petrie, D., El Feghaly, R. E., Suppes, S., Lee, B. R., Whitt, M., & Nedved, A. (2025). Nurse-Initiated Improvement for Documentation of Penicillin Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatric Urgent Care Clinics. Children, 12(8), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081087