Examination of Behavioral and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Hungarian Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

- •

- Individuals between 2 and 18 years of age at diagnosis;

- •

- JIA diagnosis according to the ILAR criteria;

- •

- Treatment with TNF inhibitor and/or methotrexate (MTX) and/or sulfasalazine (SSZ).

2.2. Main Outcome Variable

3. Procedures

3.1. Measurement of Psychological Function

3.2. Measurement of Neuropsychological Function

3.3. Disease-Specific Parameters

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Patient Characteristics and Mean Scores Were Compared Across Three Therapeutic Groups (Table 1 and Table 2)

4.2. Neuropsychological Parameters Between Treatment Groups

4.3. Treatment Group-Specific Neuropsychological Characteristics

4.4. Factors That Affect Neuropsychological Scores

4.5. Behavioral Skills Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Neuropsychological Assessment

5.2. Behavioral Skills

5.3. Our Study Has Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Iversen, M.D.; Andre, M.; von Heideken, J. Physical Activity Interventions in Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2022, 13, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandelli, Y.N.; Chambers, C.T.; Mackinnon, S.P.; Parker, J.A.; Huber, A.M.; Stinson, J.N.; Wildeboer, E.M.; Wilson, J.P.; Piccolo, O. A Systematic Review of the Psychosocial Factors Associated with Pain in Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2023, 21, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, J.E.; Luca, N.J.C.; Boneparth, A.; Stinson, J. Assessment and Management of Pain in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatr. Drugs 2014, 16, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memari, A.H.; Chamanara, E.; Ziaee, V.; Kordi, R.; Raeeskarami, S.-R. Behavioral Problems in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Controlled Study to Examine the Risk of Psychopathology in a Chronic Pediatric Disorder. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2016, 2016, 5726236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Vázquez, N.; Cabezudo-García, P.; Ortiz-Márquez, F.; Rego, G.D.; Muñoz-Becerra, L.; Manrique-Arija, S.; Fernández-Nebro, A. Evaluation of Cognitive Function in Adult Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 24, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Vázquez, N.; Ortiz-Márquez, F.; Cabezudo-García, P.; Padilla-Leiva, C.; Rego, G.D.-C.; Muñoz-Becerra, L.; Ramírez-García, T.; Lisbona-Montañez, J.M.; Manrique-Arija, S.; Mucientes, A.; et al. Longitudinal Study of Cognitive Functioning in Adults with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, J.; Klein, A.; Horneff, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2023, 43, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, D.J.; Giannini, E.H.; Reiff, A.; Cawkwell, G.D.; Silverman, E.D.; Nocton, J.J.; Stein, L.D.; Gedalia, A.; Ilowite, N.T.; Wallace, C.A.; et al. Etanercept in Children with Polyarticular Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, P.; Stobaugh, D.J.; Sherid, M.; Sifuentes, H.; Ehrenpreis, E.D. Neurological Events with Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha Inhibitors Reported to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperto, N.; Lovell, D.J.; Cuttica, R.; Woo, P.; Meiorin, S.; Wouters, C.; Silverman, E.D.; Balogh, Z.; Henrickson, M.; Davidson, J.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab plus Methotrexate for the Treatment of Polyarticular-Course Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis: Findings from an Open-Label Treatment Extension. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, D.J.; Ruperto, N.; Goodman, S.; Reiff, A.; Jung, L.; Jarosova, K.; Nemcova, D.; Mouy, R.; Sandborg, C.; Bohnsack, J.; et al. Adalimumab with or without Methotrexate in Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerloni, V.; Pontikaki, I.; Gattinara, M.; Fantini, F. Focus on Adverse Events of Tumour Necrosis Factor α Blockade in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis in an Open Monocentric Long-Term Prospective Study of 163 Patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, E.H.; Ilowite, N.T.; Lovell, D.J.; Wallace, C.A.; Rabinovich, C.E.; Reiff, A.; Higgins, G.; Gottlieb, B.; Singer, N.G.; Chon, Y.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness of Etanercept in Children with Selected Categories of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 2794–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H.; Miller, J.J.; Gottlieb, J.E. Psychosocial Adaptation in Juvenile Rheumatic Disease: A Controlled Evaluation. Health Psychol. 1987, 6, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, R.B.; Kozlowski, K.; Gerhardt, C.; Vannatta, K.; Taylor, J.; Passo, M. Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Functioning of Children with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, D.C.; Rodriguez, M.; Knight, A.M.; Rubinstein, T.B. Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Current Insights and Impact on Quality of Life, A Systematic Review. Open Access Rheumatol. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Hall, A.; Jacobs, K.; David, J. Psychological Functioning of Children and Adolescents with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Is Related to Physical Disability but Not to Disease Status. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, J.C. Overview of the Psychosocial Concerns of Young Adults with Juvenile Arthritis. Musculoskelet. Care 2004, 2, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.; Cooper, C.; Hickey, L.; Lloyd, J.; Doré, C.; Mccullough, C.; Woo, P. The Functional and Psychological Outcomes of Juvenile Chronic Arthritis in Young Adulthood. Rheumatology 1994, 33, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkol, L.; Lineberry, J.; Gottlieb, J.; Shelby, P.E.; Iii, M.; Lorig, A.K. Impact of Juvenile Arthritis on Families. An Educational Assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 1989, 2, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, N.; Jaffe, L.E. Woodcock-Johnson® IV; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, N.; Wendling, B.J. WJ III Clinical Use and Interpretation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolaro, A.; Giancane, G.; Schiappapietra, B.; Davì, S.; Calandra, S.; Lanni, S.; Ravelli, A. Clinical Outcome Measures in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2016, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnarney, E.R.; Pless, I.B.; Satterwhite, B.; Friedman, S.B. Psychological Problems of Children with Chronic Juvenile Arthritis. Pediatrics 1974, 53, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Newcomb, A.F.; Gewanter, H.L. Psychosocial Effects of Juvenile Rheumatic Disease the Family and Peer Systems as a Context for Coping. Arthritis Rheum. 1991, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, J.A.; Horgan, B.; Chaitow, J.; Champion, G.D. Psychosocial Functioning in Children and Young Adults with Juvenile Arthritis. Pediatrics 1988, 81, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granjon, M.; Rohmer, O.; Doignon-Camus, N.; Popa-Roch, M.; Pietrement, C.; Gavens, N. Neuropsychological Functioning and Academic Abilities in Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2021, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milatz, F.; Klotsche, J.; Niewerth, M.; Sengler, C.; Windschall, D.; Kallinich, T.; Dressler, F.; Trauzeddel, R.; Holl, R.W.; Foeldvari, I.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Results of an Outpatient Screening. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Trevisi, E.; Zulian, F.; Battaglia, M.A.; Viel, D.; Facchin, D.; Chiusso, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Psychological Profile in Children and Adolescents with Severe Course Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 841375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huygen, A.C.J.; Kuis, W.; Sinnema, G. Psychological, Behavioural, and Social Adjustment in Children and Adolescents with Juvenile Chronic Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, J.C.; Hall, M.A.; Pimm, T.J. Long-term Follow-up of 246 Adults with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Predictive Factors for Mood and Pain. Rheumatology 2002, 41, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, P.F.; Beukelman, T.; Schanberg, L.E.; Kimura, Y.; Colbert, R.A. Enthesitis-Related Arthritis Is Associated with Higher Pain Intensity and Poorer Health Status in Comparison with Other Categories of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry. J. Rheumatol. 2012, 39, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxter, A.J.; Wileyto, E.P.; Behrens, E.M.; Weiss, P.F. Patient-Reported Outcomes across Categories of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, A.; Chan, A.; Herrera, C.; Park, J.M.; Balboni, I.; Gerstbacher, D.; Hsu, J.J.; Lee, T.; Thienemann, M.; Frankovich, J. Profiling Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Children Undergoing Treatment for Spondyloarthritis and Polyarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 49, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MTX (n = 27) | TNF Inhibitor (n = 14) | Combination (n = 49) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 17 (62.9) | 11 (78.6) | 27 (55.1) | 0.275 a |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 8.17 ± 4.68 | 6.22 ± 4.55 | 6.32 ± 4.57 | 0.154 b |

| Age at psychological assessment, years | 10.45 ± 4.03 | 10.41 ± 4.36 | 10.45 ± 4.34 | 0.686 b |

| Duration of therapy, years | 1.56 ± 1.44 | 1.98 ± 1.39 | 1.92 ± 1.36 | 0.056 b |

| JADAS-71 I score | 5.94 ± 3.10 | 9.34 ± 3.99 | 9.28 ± 3.99 | 0.0065 b (MTX vs. Combined: 95% CI (0.80, 5, 17 ***) |

| JADAS-71 P score | 2.99 ± 2.92 | 2.88 ± 2.57 | 2.84 ± 2.49 | 0.165 b |

| JIA subtype, n (%) | NA | |||

| Oligo | 6 (22.22) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.08) | |

| Extended oligo | 2 (7.4) | 5 (35.71) | 12 (24.50) | |

| RF+ poly | 1 (3.71) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.08) | |

| RF− poly | 4 (14.81) | 3 (21.42) | 23 (46.94) | |

| ERA | 6 (22.22) | 4 (28.57) | 3 (6.12) | |

| PsA | 1 (3.71) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (2.04) | |

| UA | 7 (25.93) | 1 (7.14) | 6 (12.24) | |

| Attention (score, normal range: 90–110) | 108.78 ± 19.30 | 108.64 ± 18.45 | 111.90 ± 17.58 | 0.715 b |

| Learning (score, normal range: 90–110) | 99.96 ± 14.05 | 107.29 ± 14.97 | 105.90 ± 12.92 | 0.134 b |

| Working memory (score, normal range: 90–110) | 110.85 ± 14.35 | 110.14 ± 17.73 | 110.29 ± 12.71 | 0.982 b |

| MTX (n = 34) | TNF Inhibitor (n = 18) | Combination (n = 60) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 21 (83.33) | 15 (61.76) | 37 (61.67) | 0.210 a |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 7.89 ± 4.74 | 6.22 ± 4.55 | 6.26 ± 4.57 | 0.797 b |

| Age at psychological assessment, years | 10.11 ± 4.21 | 10.41 ± 4.36 | 10.36 ± 4.39 | 0.732 b |

| Duration of therapy, years | 1.54 ± 1.41 | 1.98 ± 1.39 | 1.91 ± 1.36 | 0.052 b |

| JADAS-71 I, score | 5.82 ± 3.08 | 9.34 ± 3.99 | 9.28 ± 3.96 | 0.0001 b (MTX vs. Combined: 95% CI (1.68, 5.52) MTX vs.TNF inhibitor: 95% CI (0.21, 5.41) c |

| JADAS-71 P, score | 2.89 ± 2.88 | 2.88 ± 2.57 | 2.83 ± 2.47 | 0.118 b |

| Behavioral variables (Nnormal/Nborderline/Npathological) | ||||

| Attachment | 31/3/0 | 16/2/0 | 55/4/1 | 0.840 a |

| Somatization | 31/3/0 | 16/2/0 | 56/3/1 | 0.795 a |

| Anxiety/depression | 31/3/0 | 17/1/0 | 54/6/0 | 1.000 a |

| Sociability | 30/4/0 | 16/2/0 | 56/3/1 | 0.599 a |

| Thinking | 31/3/0 | 16/1/1 | 55/5/0 | 0.464 a |

| Deviant behavior | 30/4/0 | 16/2/0 | 56/3/1 | 0.599 a |

| Attention | 30/4/0 | 15/3/0 | 57/3/0 | 0.152 a |

| Aggression | 30/4/0 | 17/1/0 | 54/5/1 | 0.901 a |

| Attention (Nnormal/Npathological) | Learning (Nnormal/Npathological) | Working Memory (Nnormal/Npathological) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy type | |||

| Combined | 47/2 | 46/3 | 46/3 |

| MTX | 23/4 | 20/7 | 25/2 |

| TNFi | 12/2 | 13/1 | 13/1 |

| p-value | 0.159 | 0.052 | 1.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| 0–7 years | 41/4 | 41/4 | 42/3 |

| 7.1 years | 41/4 | 38/7 | 42/3 |

| p-value | 1.000 | 0.521 | 1.000 |

| Age at NP assessment | |||

| 6–11 years | 41/2 | 38/5 | 42/1 |

| 11.1 years | 41/6 | 41/6 | 42/5 |

| p-value | 0.270 | 1.000 | 0.205 |

| Duration of therapy | |||

| 0–2 years | 53/6 | 51/8 | 55/4 |

| 2.1 years | 29/2 | 28/3 | 29/2 |

| p-value | 0.709 | 0.742 | 1.000 |

| Gender | |||

| male | 32/3 | 29/6 | 33/2 |

| female | 50/5 | 50/5 | 51/4 |

| p-value | 1.000 | 0.326 | 1.000 |

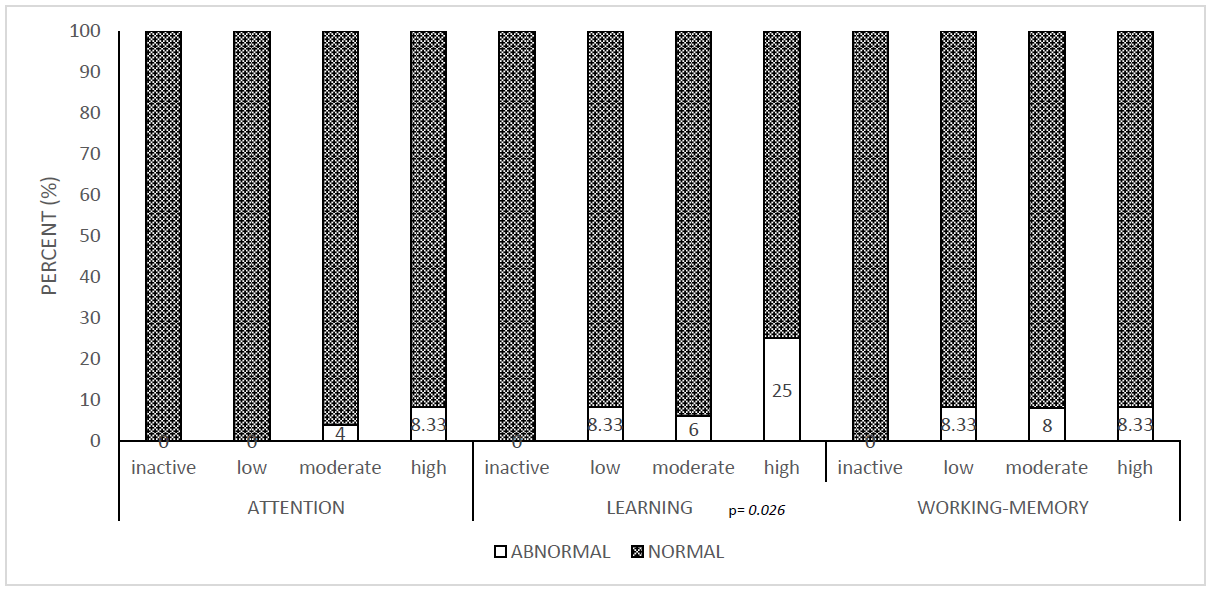

| JADAS-71-I | |||

| low | 12/0 | 11/1 | 11/1 |

| moderate | 40/5 | 43/2 | 42/3 |

| high | 30/3 | 25/8 | 31/2 |

| p-value | 0.684 | 0.026 * | 1.000 |

| JADAS-71-P | |||

| inactive | 23/2 | 23/2 | 24/1 |

| low | 34/3 | 34/3 | 34/3 |

| moderate | 17/2 | 15/4 | 18/1 |

| high | 8/1 | 7/2 | 8/1 |

| p-value | 1.000 | 0.318 | 0.819 |

| (Nn/Nb/Np) | Attachment | Somatization | Anxiety–Depression | Sociability | Thinking | Deviant Behavior | Concentration | Aggression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

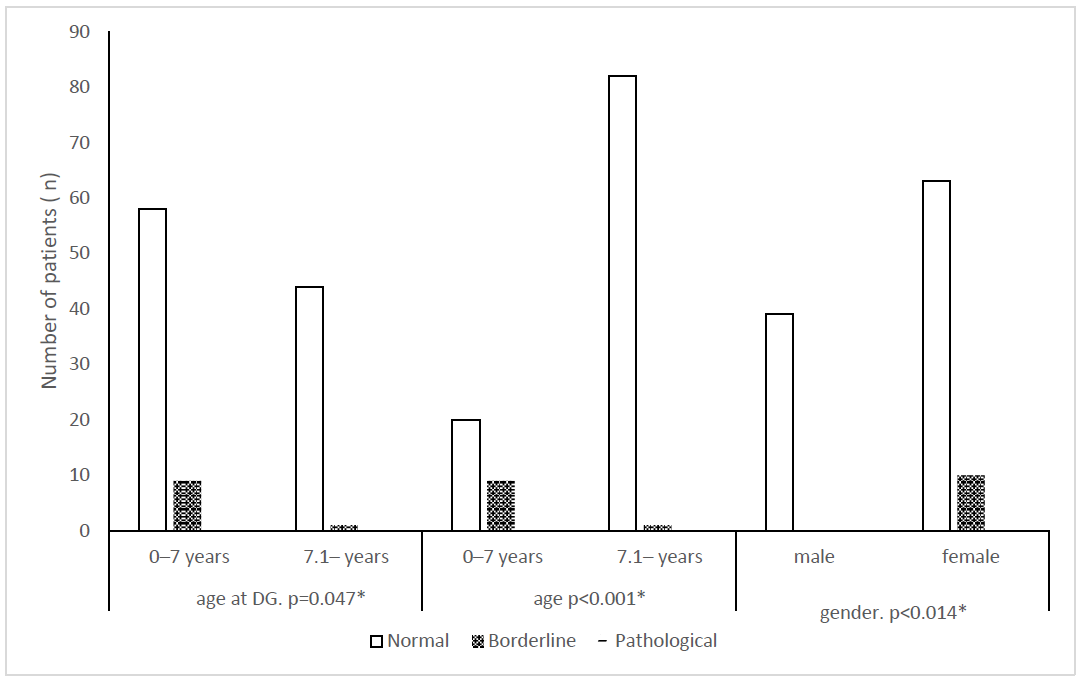

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||

| 0–7 years | 57/9/1 | 59/7/1 | 58/9/0 | 57/9/1 | 57/9/1 | 57/9/1 | 57/10/0 | 56/10/1 |

| ≥7.1. years | 45/0/0 | 44/1/0 | 44/1/0 | 45/0/0 | 45/0/0 | 45/0/0 | 45/0/0 | 45/0/0 |

| p-value | 0.010 * | 0.188 | 0.047 * | 0.010 * | 0.010 * | 0.010 * | 0.005 * | 0.005 * |

| Age at psychological assessment | ||||||||

| 0–7 years | 20/9/0 | 21/7/1 | 20/9/0 | 19/9/1 | 19/9/1 | 19/9/1 | 20/9/0 | 18/10/1 |

| ≥7.1.years | 82/1/0 | 82/1/0 | 82/1/0 | 83/0/0 | 83/0/0 | 83/0/0 | 82/1/0 | 83/0/0 |

| p-value | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Duration of therapy | ||||||||

| 0–2 years | 69/9/1 | 71/8/0 | 70/9/0 | 70/8/1 | 70/8/1 | 70/8/1 | 69/10/0 | 69/9/1 |

| 2.1– years | 33/0/0 | 32/1/0 | 32/1/0 | 32/1/0 | 32/1/0 | 32/1/0 | 33/0/0 | 32/1/0 |

| p-value | 0.073 | 0.036 * | 0.276 | 0.489 | 0.489 | 0.489 | 0.032 * | 0.489 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 36/3/0 | 37/2/0 | 39/0/0 | 37/2/0 | 38/1/0 | 38/1/0 | 38/1/0 | 37/2/0 |

| Female | 66/6/1 | 66/6/1 | 63/10/0 | 65/7/1 | 64/8/1 | 64/8/1 | 64/9/0 | 64/8/1 |

| p-value | 1.000 | 0.811 | 0.014 * | 0.667 | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.160 | 0.667 |

| JADAS-71-I | ||||||||

| Low | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 | 12/0/0 |

| Moderate | 51/5/0 | 52/4/0 | 49/7/0 | 50/5/1 | 50/5/1 | 47/8/1 | 51/5/0 | 49/6/1 |

| High | 39/4/1 | 39/4/1 | 41/3/0 | 40/4/0 | 40/4/0 | 43/1/0 | 39/5/0 | 40/4/0 |

| p-value | 0.719 | 0.650 | 0.446 | 0.890 | 0.890 | 0.090 | 0.636 | 0.814 |

| JADAS-71-P | ||||||||

| Inactive | 31/1/0 | 28/4/0 | 29/3/0 | 28/3/1 | 28/4/0 | 28/4/0 | 27/5/0 | 29/3/0 |

| Low | 41/6/1 | 44/3/1 | 44/4/0 | 44/4/0 | 43/4/1 | 43/4/1 | 44/4/0 | 43/5/0 |

| Moderate | 21/1/0 | 22/0/0 | 19/3/0 | 21/1/0 | 21/1/0 | 21/1/0 | 21/1/0 | 20/1/1 |

| High | 9/1/0 | 9/1/0 | 10/0/0 | 9/1/0 | 10/0/0 | 10/0/0 | 10/0/0 | 9/1/0 |

| p-value | 0.564 | 0.498 | 0.802 | 0.831 | 0.889 | 0.889 | 0.498 | 0.692 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garan, D.; Lengvári, L.; Ponyi, A.; Szabados, M.; Gergev, G.; Bozi, I.; Wijker, W.; Constantin, T. Examination of Behavioral and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Hungarian Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081057

Garan D, Lengvári L, Ponyi A, Szabados M, Gergev G, Bozi I, Wijker W, Constantin T. Examination of Behavioral and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Hungarian Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children. 2025; 12(8):1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081057

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaran, Diána, Lilla Lengvári, Andrea Ponyi, Márton Szabados, Gyurgyinka Gergev, Imre Bozi, Wouter Wijker, and Tamás Constantin. 2025. "Examination of Behavioral and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Hungarian Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Children 12, no. 8: 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081057

APA StyleGaran, D., Lengvári, L., Ponyi, A., Szabados, M., Gergev, G., Bozi, I., Wijker, W., & Constantin, T. (2025). Examination of Behavioral and Neuropsychological Characteristics of Hungarian Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children, 12(8), 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081057