Understanding Parental Representations Across the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings and Clinical Implications

Abstract

Highlights

- Parental mental representations (PMRs) develop during pregnancy and continue to evolve in the postnatal period.

- The current literature shows significant methodological heterogeneity and an underrepresentation of fathers and dyadic perspectives.

- Early identification of nonbalanced PMRs may help prevent relational difficulties and promote secure attachment.

- Future studies should adopt longitudinal, systemic, and culturally inclusive approaches to better capture the complexity of early parenthood and inform preventive mental health strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategies

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Process

2.4. Quality Assessment Methods

3. Results

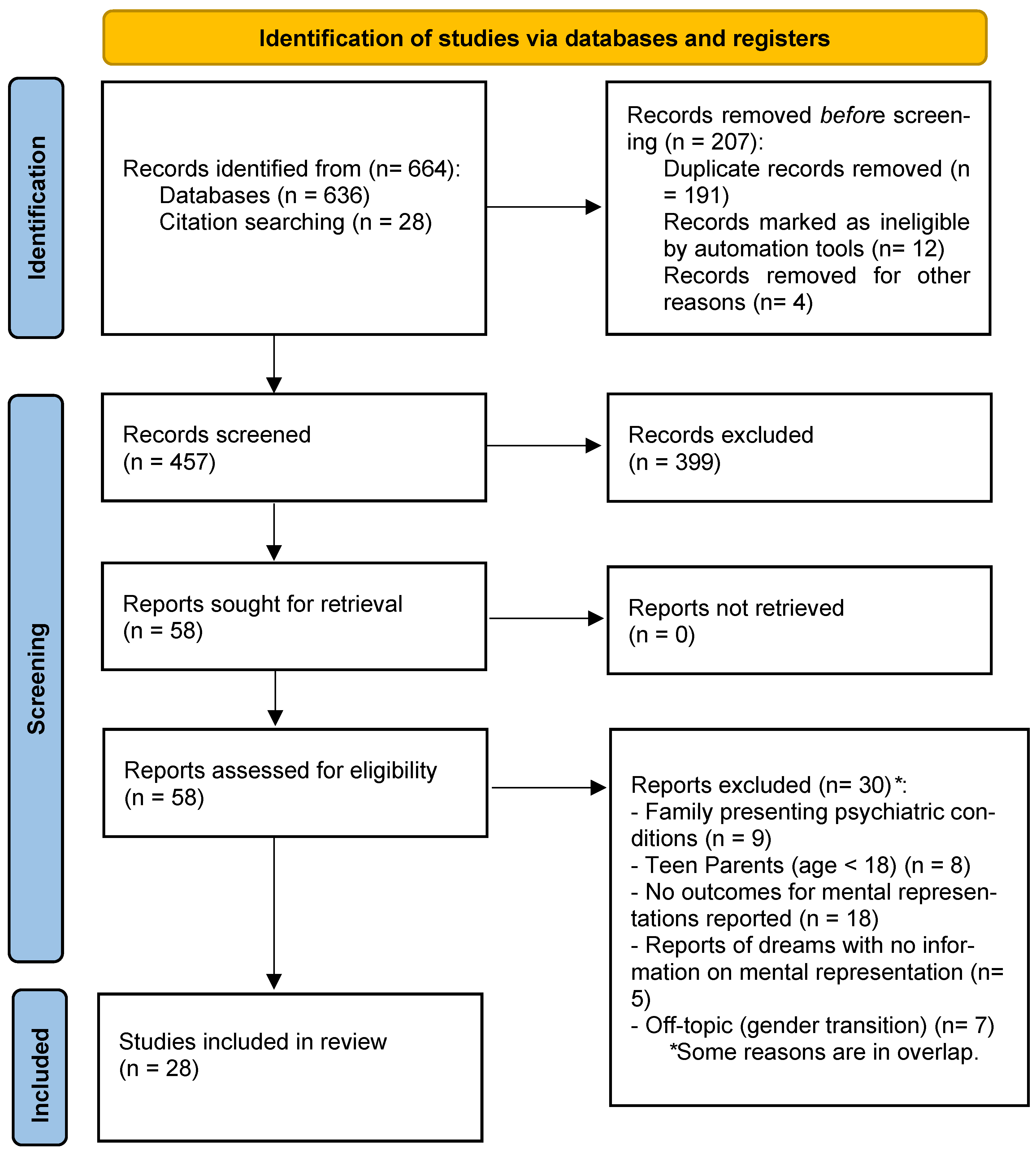

3.1. Study Selection and Inclusion

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3.1. Parental Mental Representations

3.3.2. Parental Mental Representations and Reflective Functioning

3.3.3. Parental Mental Representations and Risk Factors

3.3.4. Parental Representations and Child Attachment

3.3.5. Parental Mental Representations and Postnatal Experience

| Author (Year) | Sample Size/Parent | Mean Age (M)/Age Range (AR) | Assessment Period | Assessment Tool for Mental Representations | Investigated Dimensions (Outcomes) | Main Findings |

| Alismail et al., 2021 [35] | 47 mothers | M = 25.74 | Third trimester to 7 months postpartum | WMCI (PP); PI-R; PDI (PP) | Associations between maternal reflective functioning (prenatal and postnatal) and maternal representations at 7 months postpartum. | Representations categorized as distorted (38.3%), balanced (36.2%), and disengaged (25.5%). Lower prenatal MRF levels were associated with disengaged representations. Higher MRF was linked to balanced representations. No significant difference in MRF scores between distorted and disengaged groups. Some inconsistencies found (e.g., high MRF with distorted representations). |

| Ammaniti et al., 1992 [4] | 23 primiparous mothers | M = 29 AR = 20–34 years | 28–32 weeks of pregnancy | IRMAG | Content and structure of maternal representations. | Clear differentiation between self as mother and baby representations. Strong positive correlations across matched dimensions of self and baby representations. Social dependency inversely related to openness to change. Baby’s characteristics perceived as more similar to the father than to the mother. Mothers emphasized differentiation from their own mothers. |

| Ammaniti et al., 2006 [36] | 130 fathers | M = 33 AR = 23–52 years | 28–32 weeks of pregnancy | IRPAG | Organization of paternal representations and parenting styles. | Positive correlations between self and baby representations. Correlation between richness of perceptions, openness to change, emotional engagement, and the emergence of fantasies Three representation types: Integrated (n = 72), Restricted/Disinvested (n = 44), Ambivalent/Unintegrated (n = 14) |

| Ammaniti et al., 2013 [37] | 666 mothers (411 low-risk; 255 at psychosocial/depressive risk) | M = 31.67 AR= 23–43 years | Mid-6th to mid-7th month of pregnancy | IRMAG | Prevalence of representation categories in risk vs. non-risk groups. | Three representation categories identified: Integrated, Restricted/Disinvested, Ambivalent/Unintegrated. Risk-group mothers showed lower scores across most dimensions and higher social dependency. Self-as-mother representations more articulated than representations of the child. |

| Bailes et al., 2024 [38] | 297 mothers | M = 31.17 AR: 21–44 years | Second trimester to 6 months postpartum | WMCI | Link between perception richness, pregnancy acceptance, intention, sensitivity, and warmth. | Greater pregnancy intentionality predicted higher acceptance and perception richness in the third trimester. These elements mediated higher caregiver sensitivity and warmth in early interactions. |

| Benoit et al., 1997 [39] | 96 mothers | M = 29.17 AR = 20–39 years | Third trimester to 12 months postpartum | WMCI | Predictive validity and stability of maternal representations; associations with attachment classification. | Balanced WMCI representations were strongly associated with secure attachment (Strange Situation). Prenatal WMCI categories remained stable at 11 months, particularly balanced and distorted types. No stability for disengaged representations. Significant concordance between prenatal WMCI and infant attachment classifications |

| Coleman et al., 1999 [33] | 31 mothers | M = 25 AR = 16–32 years | Third trimester to 3 weeks postpartum | PMES; WPL-R | Prenatal expectations and postnatal maternal attitudes. | Higher PMES scores predicted more positive postnatal maternal attitudes (WPL-R). Low PMES scores correlated with negative postnatal adjustment. Moderate prenatal expectations did not predict more positive postnatal attitudes. |

| Delmore-Ko et al., 2000 [40] | 59 first-time parent couples | M (mothers) = 27.3 AR (mothers) = 18–40 years M (fathers) = 30.1 AR (fathers) = 19–48 | Third trimester to 18 months postpartum | Prenatal Interview | Future parenting expectations and relationship changes. | Four maternal themes: Enthusiasm, Anxiety, Coping, Uncertainty. Five paternal themes: same as mothers plus Socialization. Couples showed the highest adjustment in the third trimester. Marital satisfaction declined after parenthood for both parents. |

| Flykt et al., 2011 [53] | 378 parent couples | M (mothers) = 33.3 M (fathers) = 34.2 | Second trimester to 12 months postpartum | Subjective Family Picture Test (child-related items) | Parental expectations and parenting stress. | High prenatal expectations of intimacy and autonomy with the baby associated with lower parenting stress at 2 and 12 months. Maternal expectations about emotional intimacy with the baby predicted lower stress more than paternal ones. Moderate paternal expectations of autonomy predicted lower stress at 2 months. Mothers’ expectations positively changed postnatally; paternal expectations remained mostly stable. |

| Gress-Smith at al., 2013 [54] | 210 mothers | M = 27.4 | Third trimester | PESMA | Maternal expectations and their correlates. | Higher expectations of maternal role fulfillment and partner support were linked to lower depressive symptoms and higher perceived support. Married/cohabiting women had higher expectations of partner support. Higher expectations of satisfaction from motherhood were associated with readiness to become a mother, greater financial difficulty, and previous childcare experience. High family support expectations were linked to younger age, fewer children, higher education, and financial challenges |

| Huth-Bocks et al., 2004 [41] | 206 mothers | M = 25.4 AR = 18–40 years | Third trimester to 1 year postpartum | WMCI | Predictive value of maternal representations for attachment quality. | Strong correlations between representations of the child and of the self as mother. Negative childhood attachment experiences linked to lower prenatal support and less secure prenatal representations. More prenatal risk factors correlated with less secure representations. Secure prenatal representations predicted more secure mother–infant attachment. |

| Ilicali, Fisek, 2004 [42] | 45 primiparous mothers | M = 22.96 | 4–8th month of pregnancy to 7 months postpartum | Entretien R1, MRI | Maternal representations before and after birth. | Pregnant women often identified their future children with their husbands; postpartum, this shifted toward self-identification. Mothers sought differentiation from their own mothers, favoring idealized maternal roles. Postpartum narratives were more coherent, flexible, and richer than prenatal ones. |

| Innamorati et al., 2010 [43] | 162 mothers divided into: Early pregnancy (EP, n = 55), Mid pregnancy (MP, n = 51), Late pregnancy (LP, n = 55) | M (EP) = 30.3 M (MP) = 30.2 M (LP) = 31.8 | Varies by group (pre-5th month, 6–7th month, 8–9th month) | The Breakfast Inteview MIPS | Evolution of the maternal constellation. | Mid-pregnancy (MP) mothers scored highest on all four themes (growth concern, affective involvement, support, identity transformation). Maternal constellation peaked in richness and specificity during the 6–7th month. |

| Lis et al., 2000 [44] | 112 first-time parent couples | M (mothers) = 24 M (fathers) = 28 | 7th month of pregnancy | CGG Reflective Functioning Scale | Parenting styles and reflective function. | Most common score was 3 on reflective function. Mothers scored higher than fathers. Reflective function was lower in the “child” area than in others. |

| Lis et al., 2004 [32] | 112 fathers | M = 28 | 7th month of pregnancy | CGG Reflective Functioning Scale | Parenting styles and reflective function. | Low reflective functioning predicted instrumental or observer parenting styles. Moderate-to-high reflective functioning predicted expressive style. |

| Madsen et al., 2007 [52] | 41 fatehrs | - | 6th month of pregnancy to 5 months postpartum | Father Attachment Interview | Paternal reflective functioning and caregiving representations. | Fathers’ ability to reflect on their child’s mental states was associated with their own caregiving models (especially with maternal caregiving). Reflective functioning was predicted by internalized models based on closeness, compassion, and understanding. |

| Pajulo et al., 2001 [55] | 380 mothers (84 at risk) | M = 27.5 | 3rd to 8th month of pregnancy | IRMAG | Content of maternal representations and risk factors. | At-risk mothers showed lower scores in representations of the baby, self as mother and woman, their partner, and their own mother. Positive representations of the baby were more similar across risk and non-risk groups. |

| Pajulo et al., 2015 [56] | Pilot: 124 mothers, 82 fathers|Cohort: 600 mothers, 600 fathers | M (mothers in cohort) = 30.1 M (fathers in cohort) = 32.1 | 20–32 weeks of gestation | P-PRFQ PI | Development of a prenatal reflective functioning questionnaire. | Mothers scored higher in considering mental states and relational flexibility. Both mothers and fathers showed similar levels of perceived opacity of mental states. Maternal reflective functioning correlated with PI scores. |

| Pearce and Ayers, 2004 [57] | 51 mothers | M = 31 | Week 39 of gestation to 3 weeks postpartum | ICQ, Mother–Baby Self-Rating Scale | Stability of maternal perception and its relation to bonding. | Expectations during pregnancy correlated with postnatal perceptions and mother–infant bonding. No association found between expectation–evaluation mismatch and poor bonding or postnatal distress. Negative expectations were associated with higher risk of poor bonding. |

| Ruble et al., 1990 [58] | Cross-sectional: 667 mothers|Longitudinal: 48 mothers | M (cross-sectional) = 29 AR (cross-sectional) = 18–42 M (longitudinal) = 29 AR (longitudinal) = 18–37 | Cross-sectional: 2 years pre-conception to 3 months postpartum Longitudinal: 9th month pregnancy to 16 months postpartum | CAQ MSDQ | Changes in self-definition. | Self-perceptions were stable by the 9th month. Postpartum women felt more involved and protective. Across phases: increases in maternal self-confidence and information-seeking; decreases in maternal concerns and sexual interest. |

| Rusanen et al., 2018 [31] | 1646 mothers | M = 30.2 | 32nd week of pregnancy to 24 months postpartum | RUB-M | Moderating factors in the development of maternal representations. | Positive expectations about bonding, caregiving, and routines were linked to better family atmosphere. Stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were associated with more negative expectations. Higher maternal education was linked to fewer positive expectations and more caregiving concerns. |

| Tambelli et al., 2020 [46] | 50 first-time parent couples | M (mothers) = 33.88 M (fathers) = 36.90 | 7th month of pregnancy to 18 months postpartum | IRMAG-R IRPAG-R EAS Strange Situation | Prenatal representations, emotional availability, and infant attachment. | Strong links between prenatal representations, emotional availability, and attachment categories. For mothers, prenatal representations directly influenced attachment. For fathers, emotional availability mediated the link with attachment quality. |

| Theran et al., 2005 [47] | 180 mothers | M = 25 AR = 18–40 years | Third trimester to 1 year postpartum | WMCI | Stability and change in maternal mental representations | 71% showed stable representations over time. Balanced representations were most stable. Nonbalanced types were associated with low income, single parenting, and prenatal abuse. |

| Thun-Hohenstein et al., 2008 [59] | 73 mothers | M = 29.2 AR = 19–39 years | Third trimester to 3 months postpartum | CCQ | Predictive value of prenatal representations on early mother–infant interaction. | No link between maternal competence and predictive variables. Desirability of unborn child predicted eye contact in still-face procedure. Readiness for interaction was linked to prenatal relational representations. Higher parental competence found in mothers of boys, younger mothers, and those with more education. |

| Vizziello et al., 1993 [45] | 42 mothers | M = 29 AD = 20–35 years | 7th month of pregnancy to 4 months postpartum | Interview on Maternal Representations | Role of maternal representations in early bonding and clinical assessment. | Four representation themes: Desire-driven, Defensive, Fear-based, Disorganized. Representations of self as woman and of partner were stable; those of self as mother and of the baby were less stable. Integration process occurred between maternal and female identity. |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2014 [22] | 243 fathers | M = 34.01 AD = 27–49 years | 26th week of pregnancy | WMCI PAAS | Meaning of the unborn child for the father. | Fathers were more often in the “disengaged” category, mothers in “balanced”. Prenatal attachment quality was negatively associated with depressive and anxious traits. Younger age, first-time fatherhood, and higher education linked to better prenatal attachment. |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2014 [23] | 217 fathers | M = 34.11 Range = 22.31–49.60 | Week 26 of pregnancy to 6 months postpartum | WMCI | Stability and predictors of paternal representations. | Over half had nonbalanced representations prenatally. Fathers with nonbalanced prenatal representations more likely to change postnatally. First-time fathers had more balanced prenatal representations. No significant effect of paternal mental well-being on representations. Conscientious and agreeable fathers had more balanced representations across time |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2015 [34] | 294 mothers 225 fathers | M (mothers) = 31.60 AR (mothers) = 17–42 M (fathers) = 34.09 AR (fathers) = 22–49 | 26th week of pregnancy to 6 months postpartum | WMCI | Prenatal risk factors and stability of representations. | Mothers were more likely to develop balanced and less likely disengaged representations postpartum. Fathers showed similar patterns but increased distorted representations after birth. Maternal prenatal risk was linked to distorted representations; no such link in fathers. Disengaged prenatal mothers remained disengaged; balanced fathers remained balanced postnatally. |

| Author (Year) | Demographic Data and Risk Factors | Main Characteristics |

| Alismail et al., 2021 [35] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Income (yearly) | 51% single 78.7% black 27.7% high school; 44.7% college 70% < 30,000 $ |

| Ammaniti et al., 1992 [4] | n/a | n/a |

| Ammaniti et al., 2006 [36] | n/a | n/a |

| Ammaniti et al., 2013 [37] | Depressive risk Psychosocial Risk Assessed via CES-D | Low risk = 411 mothers High risk = 255 mothers |

| Bailes et al., 2024 [38] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Income (yearly) | 15% single 85% Caucasian 75% bachelor’s degree or higher median 90,000–150,000 $ |

| Benoit et al., 1997 [39] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Income | 5% single Caucasian Range = 9–27 years Upper-middle-class background |

| Coleman et al., 1999 [33] | Marital Status Education Employing | 16% single 42% bachelor’s degree or higher Full time |

| Delmore-Ko et al., 2000 [40] | Marital Status Education Employing Psychological Risk | Average of marriage = 4.2 35% bachelor’s degree or higher Both parents = full time Stress; depressive symptoms; self-esteem; marital adjustment |

| Flykt et al., 2011 [53] | n/a | n/a |

| Gress-Smith at al., 2013 [54] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Economic hardship Depressive Symptoms Social support | 7% divorced; 15% single 86% Mexican 5.7% bachelor’s degree or higher Average = −0.03 Range = 0–25; average = 5.4 Middle-high |

| Huth-Bocks et al., 2004 [41] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Income (monthly) Domestic violence in life Domestic violence in pregnancy | 50% single 63% Caucasian 13% bachelor’s degree or higher Range = 0–$9500; Average = $1451 75% 44% |

| Ilicali, Fisek, 2004 [42] | Marital Status Education | Average = 2 years Average = 11 years |

| Innamorati et al., 2010 [43] | Race/Ethnicity Education | 100% Italian 17% middle school or lower |

| Lis et al., 2000 [44] | Socioeconomic status Assessed via Four-Factor Index | Medium socioeconomic level |

| Lis et al., 2004 [32] | Education Socioeconomic status Assessed via Four-Factor Index | 52% high school Medium socioeconomic level |

| Madsen et al., 2007 [52] | n/a | n/a |

| Pajulo et al., 2001 [55] | Risk conditions group screening for any of the variables considered | Depressive symptoms; Risk for addiction; Social Environmental difficulties; Lack for social support. |

| Pajulo et al., 2015 [56] | Marital Status Education Income (monthly) | 98% married 68% high levels 24% < 2000 € |

| Pearce and Ayers, 2004 [57] | Marital Status Race/Ethnicity Education Socioeconomic status | 100% in a relationship 76% European 27% bachelor’s degree or higher Class 2–3 = 88% |

| Ruble et al., 1990 [58] | Race/Ethnicity Education | 98% Caucasian 70% bachelor’s degree or higher |

| Rusanen et al., 2018 [31] | Education Income (monthly) Psychological Screening | 33.4% bachelor’s degree or higher 74% < 2000 € Anxiety; Depressive symptoms; Family Atmosphere. |

| Tambelli et al., 2020 [46] | Psychological Screening | Anxiety; Depressive symptoms; Emotional Availability. |

| Theran et al., 2005 [47] | Psychological Screening | Depressive symptoms |

| Thun-Hohenstein et al., 2008 [59] | Education Psychological Screening | 44% Low Depressive symptoms |

| Vizziello et al., 1993 [45] | n/a | n/a |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2014 [22] | Education Employing Psychological Screening | 64.2% bachelor’s degree or higher 96.6% Anxiety; Depressive symptoms |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2014 [23] | Education Employing | 65.4% > 9 years 96.3% |

| Vreeswijk et al., 2015 [34] | Education Employing First child | 64% > 9 87% of mothers; 97.9% of fathers 51.6% |

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slade, A.; Grienenberger, J.; Bernbach, E.; Levy, D.; Locker, A. Maternal reflective functioning, attachment, and the transmission gap: A preliminary study. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum, K.L.; Dayton, C.J.; Muzik, M. Infant social and emotional development: The emergence of self in a relational context. In Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 3rd ed.; Zeanah, C.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti, M.; Baumgartner, E.; Candelori, C.; Perucchini, P.; Pola, M.; Tambelli, R.; Zampino, F. Representations and narratives during pregnancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 1992, 13, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.N.; Anders, T.F. The motherhood constellation: A unified view of parent-infant psychotherapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeswijk, C.M.; Maas, A.J.B.; van Bakel, H.J. Parental representations: A systematic review of the working model of the child interview. Infant Ment. Health J. 2012, 33, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, M.; Steele, H.; Leigh, T.; Kennedy, R.; Mattoon, G.; Target, M. Attachment, the reflective self, and borderline states: The predictive specificity of the Adult Attachment Interview and pathological emotional development. In Attachment Theory: Social, Developmental and Clinical Perspectives; Goldberg, S., Muir, R., Kerr, J., Eds.; Analytic Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1995; Chapter 9; pp. 223–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.; Target, M. Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self; Other Press Other Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zeegers, M.A.J.; Colonnesi, C.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Meins, E. Parental mentalizing, sensitivity, and the quality of parenting: A meta-analytic review. Dev. Rev. 2017, 42, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Buttitta, K.V.; Smiley, P.A.; Kerr, M.L.; Rasmussen, H.F.; Querdasi, F.R.; Borelli, J.L. In a father’s mind: Paternal reflective functioning, sensitive parenting, and protection against socioeconomic risk. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Bradley, R.H.; Hofferth, S.; Lamb, M.E. Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.; Grossmann, K.E.; Fremmer-Bombik, E.; Kindler, H.; Scheuerer-Englisch, H.; Zimmermann, A.P. The uniqueness of the child–father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Soc. Dev. 2002, 11, 301–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmstedt, A.; Collins, A. Psychological functioning and predictors of father–infant relationship in IVF fathers and controls. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, B.L. Paternal socio-psychological factors and infant attachment: The mediating role of synchrony in father–infant interactions. Infant Behav. Dev. 2002, 25, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Hum. Dev. 2004, 47, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani, P.; Stein, A.; Evans, J.; O’Connor, T.G. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: A prospective population study. Lancet 2005, 365, 2201–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, A.; Kristiansson, R.; Oberklaid, F.; Bremberg, S. Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2008, 97, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, H.; Steele, M.; Fonagy, P. Associations among attachment classifications of mothers, fathers, and their infants. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann-Villalba, P.; Gschwendt, M.; Schmidt, M.H.; Laucht, M. Father–infant interaction patterns as precursors of children’s later externalizing behavior problems: A longitudinal study over 11 years. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; De Wolff, M.S. In search of the absent father—Meta-analyses of infant-father attachment: A rejoinder to our discussants. Child Dev. 1997, 68, 604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstedt, J.; Korja, R.; Vilja, S.; Ahlqvist-Björkroth, S. Fathers’ prenatal attachment representations and the quality of father–child interaction in infancy and toddlerhood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vreeswijk, C.M.; Maas, A.J.; Rijk, C.H.; van Bakel, H.J. Fathers’ experiences during pregnancy: Paternal prenatal attachment and representations of the fetus. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2014, 15, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeswijk, C.M.; Maas, A.J.B.; Rijk, C.H.; Braeken, J.; van Bakel, H.J. Stability of fathers’ representations of their infants during the transition to parenthood. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2014, 16, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, L.S.; Slade, A.; Close, N.; Webb, D.L.; Simpson, T.; Fennie, K.; Mayes, L.C. Minding the Baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home visiting program. Infant Ment. Health J. 2013, 34, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijssens, L.; Bleys, D.; Casalin, S.; Vliegen, N.; Luyten, P. Parental attachment dimensions and parenting stress: The mediating role of parental reflective functioning. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2025–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton, C.J.; Levendosky, A.A.; Davidson, W.S.; Bogat, G.A. The child as held in the mind of the mother: The influence of prenatal maternal representations on parenting behaviors. Infant Ment. Health J. 2010, 31, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P.; Nijssens, L.; Fonagy, P.; Mayes, L.C. Parental reflective functioning: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Psychoanal. Study Child. 2017, 70, 174–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley Sons Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2019; Chapter 8; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Tambelli, R.; Tosto, S.; Favieri, F. Psychiatric Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanen, E.; Lahikainen, A.; Pölkki, P.; Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O.; Paavonen, E.J. The significance of supportive and undermining elements in the maternal representations of an unborn baby. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018, 36, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, A.; Zennaro, A.; Mazzeschi, C.; Pinto, M. Parental styles in prospective fathers: A research carried out using a semistructured interview during pregnancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 2004, 25, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, P.; Nelson, E.S.; Sundre, D.L. The relationship between prenatal expectations and postnatal attitudes among first-time mothers. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1999, 17, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeswijk, C.M.; Rijk, C.H.; Maas, A.J.B.; van Bakel, H.J. Fathers’ and mothers’ representations of the infant: Associations with prenatal risk factors. Infant Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alismail, F.; Stacks, A.M.; Wong, K.; Brown, S.; Beeghly, M.; Thomason, M. Maternal caregiving representations of the infant in the first year of life: Associations with prenatal and concurrent reflective functioning. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammaniti, M.; Tambelli, R.; Odorisio, F. Intervista clinica per lo studio delle rappresentazioni paterne in gravidanza: IRPAG. Età Evol. 2006, 85, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti, M.; Tambelli, R.; Odorisio, F. Exploring maternal representations during pregnancy in normal and at-risk samples: The use of the interview of maternal representations during pregnancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 2013, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailes, L.G.; Fleming, B.; Ford, J.; Macfarlane, M.; Carrow, C.; Humphreys, K.L.; Zeanah, C.H. Prenatal representations link pregnancy intention to observed caregiving. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, D.; Parker, K.C.; Zeanah, C.H. Mothers’ representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants’ attachment classifications. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmore-Ko, P.; Pancer, S.M.; Hunsberger, B.; Pratt, M. Becoming a parent: The relation between prenatal expectations and postnatal experience. J. Fam. Psychol. 2000, 14, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth-Bocks, A.C.; Levendosky, A.A.; Bogat, G.A.; Von Eye, A. The impact of maternal characteristics and contextual variables on infant–mother attachment. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicali, E.T.; Fisek, G.O. Maternal representations during pregnancy and early motherhood. Infant Ment. Health J. 2004, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innamorati, M.; Sarracino, D.; Dazzi, N. Motherhood constellation and representational change in pregnancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 2010, 31, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zennaro, A.; Mazzeschi, C. Application of the reflective self-function scale to the clinical interview for couples during pregnancy. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 87, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizziello, G.F.; Antonioli, M.E.; Cocci, V.; Invernizzi, R. From pregnancy to motherhood: The structure of representative and narrative change. Infant Ment. Health J. 1993, 14, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambelli, R.; Trentini, C.; Dentale, F. Predictive and incremental validity of parental representations during pregnancy on child attachment. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theran, S.A.; Levendosky, A.A.; Anne Bogat, G.; Huth-Bocks, A.C. Stability and change in mothers’ internal representations of their infants over time. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanah, C.H.; Benoit, D.; Hirshberg, L.; Barton, M.L.; Regan, C. Mothers’ representations of their infants are concordant with infant attachment classifications. Dev. Issues Psychiatry Psychol. 1994, 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zennaro, A.; Ascari, M. Il colloquio con giovani coppie in attesa del primogenito. In Il Colloquio Come Strumento Psicologico; Lis, A., Venuti, P., De Zordo, M.R., Eds.; Giunti: Firenze, Italia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, A.; Zennaro, A. A semistructured interview with parents-to-be used during pregnancy: Preliminary data. Infant Ment. Health J. 1997, 18, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.N. The representation of relational patterns: Developmental considerations. In Relationship Disturbances in Early Childhood: A Developmental Approach; Sameroff, A.J., Emde, R.N., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, S.A.; Lind, D.; Munck, H. Men’s abilities to reflect their infants’ states of mind. Nord. Psychol. 2007, 59, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flykt, M.; Lindblom, J.; Punamäki, R.-L.; Poikkeus, P.; Repokari, L.; Unkila-Kallio, L.; Vilska, S.; Sinkkonen, J.; Tiitinen, A.; Almqvist, F.; et al. Prenatal expectations in transition to parenthood: Former infertility and family dynamic considerations. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gress-Smith, J.L.; Roubinov, D.S.; Tanaka, R.; Cirnic, K.; Gonzales, N.; Enders, C.; Luecken, L.J. Prenatal expectations in Mexican American women: Development of a culturally sensitive measure. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2013, 16, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajulo, M.; Savonlahti, E.; Sourander, A.; Piha, J.; Helenius, H. Prenatal maternal representations: Mothers at psychosocial risk. Infant Ment. Health J. 2001, 22, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajulo, M.; Tolvanen, M.; Karlsson, L.; Halme-Chowdhury, E.; Öst, C.; Luyten, P.; Mayes, L.; Karlsson, H. The prenatal parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Exploring factor structure and construct validity of a new measure in the Finn brain birth cohort pilot study. Infant Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, H.; Ayers, S. The expected child versus the actual child: Implications for the mother–baby bond. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2005, 23, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, D.N.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Fleming, A.S.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Stangor, C.; Deutsch, F. Transition to motherhood and the self: Measurement, stability, and change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thun-Hohenstein, L.; Wienerroither, C.; Schreuer, M.; Seim, G.; Wienerroither, H. Antenatal mental representations about the child and mother–infant interaction at three months post partum. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pridham, K.F.; Chang, A.S. What being the parent of a new baby is like: Revision of an instrument. Res. Nurs. Health 1989, 12, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touliatos, J.; Perlmutter, B.F.; Straus, M.A. Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, J.E.; Freeland, C.A.B.; Lounsbury, M.L. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Dev. 1979, 50, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.K. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 21, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, F.M.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Fleming, A.; Ruble, D.N.; Stangor, C. Information seeking and maternal self-definition during the transition to motherhood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloger-Tippelt, G. A process model of the pregnancy course. Hum. Dev. 1983, 26, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment, a Psychological Study of the Strange Situation, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, A. Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanah, C.H.; Benoit, D. Clinical applications of a parent perception interview in infant mental health. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1995, 4, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, D.S.; Coots, T.; Zeanah, C.H.; Davies, M.; Coates, S.W.; Trabka, K.A.; Randall, D.M.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Myers, M.M. Maternal mental representations of the child in an inner-city clinical sample: Violence-related posttraumatic stress and reflective functioning. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, H.J.; Booth, C.R.; Luyten, P.; Bridgett, D.J.; Mayes, L.C. Investigating the association between parental reflective functioning and distress tolerance in motherhood. Infant Behav. Dev. 2015, 40, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Altenburger, L.E.; Bower, D.J. Investment in fatherhood and the quality of fathers’ interactions with their preschool-aged children. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 541–552. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Haines, J.; Charlton, B.M.; VanderWeele, T.J. Positive parenting improves multiple aspects of health and well-being in young adulthood. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, P.A.; Cowan, C.P. When Partners Become Parents: The Big Life Change for Couples; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.R.; Kirby, J.N.; Tellegen, C.L.; Day, J.J. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Script | Databases |

|---|---|

| Parent* OR caregiver* OR mother* OR father* AND mental representation* OR reflective functioning | Scopus; APA PSYCARTICLES/APA PSYCINFO; Web of Sciences. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tambelli, R.; Del Proposto, L.; Favieri, F. Understanding Parental Representations Across the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings and Clinical Implications. Children 2025, 12, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081051

Tambelli R, Del Proposto L, Favieri F. Understanding Parental Representations Across the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings and Clinical Implications. Children. 2025; 12(8):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081051

Chicago/Turabian StyleTambelli, Renata, Ludovica Del Proposto, and Francesca Favieri. 2025. "Understanding Parental Representations Across the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings and Clinical Implications" Children 12, no. 8: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081051

APA StyleTambelli, R., Del Proposto, L., & Favieri, F. (2025). Understanding Parental Representations Across the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Empirical Findings and Clinical Implications. Children, 12(8), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081051