Tiny Beads, Big Problems: Water Bead Ingestions—A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Informed Consent

2.2. Reporting

3. Patient Information

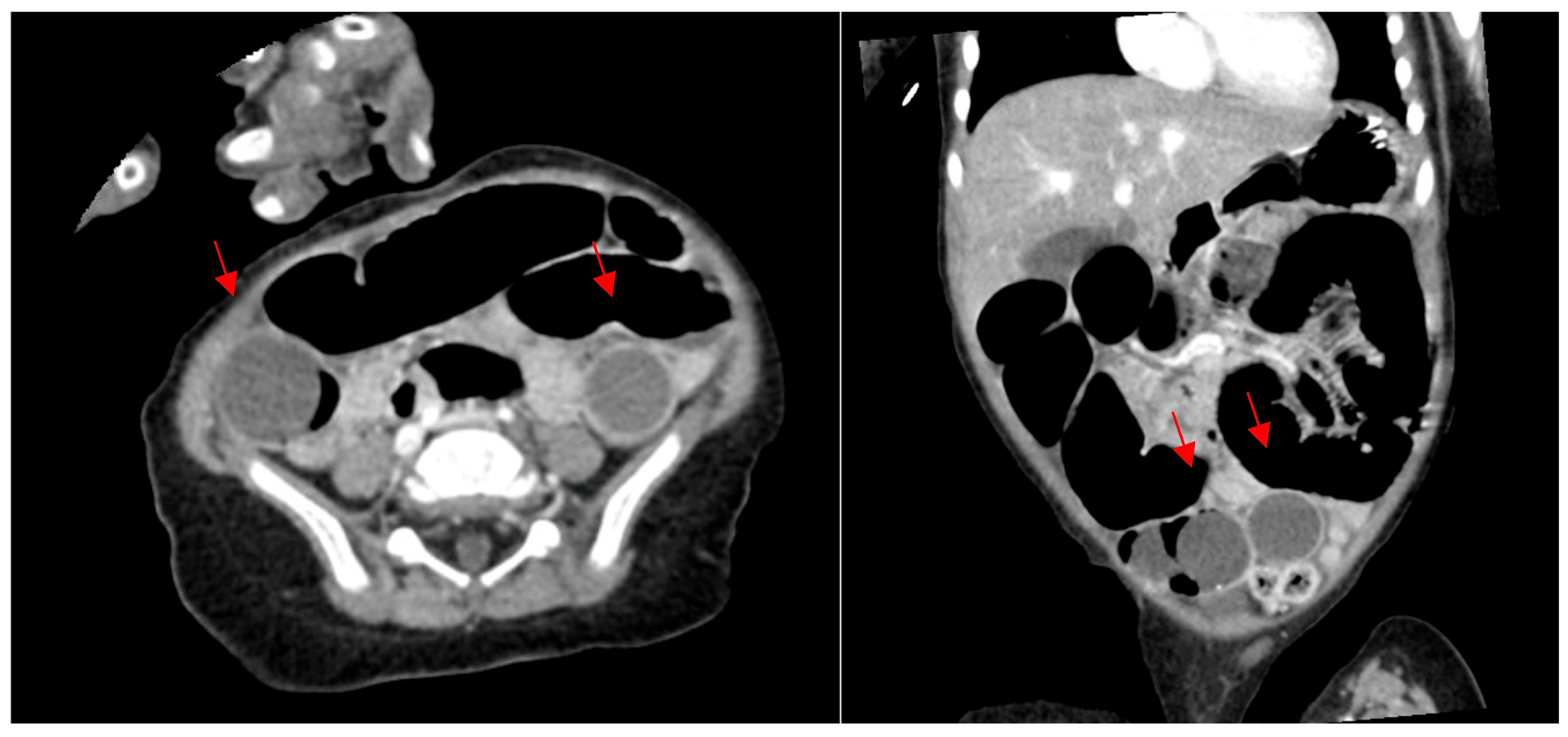

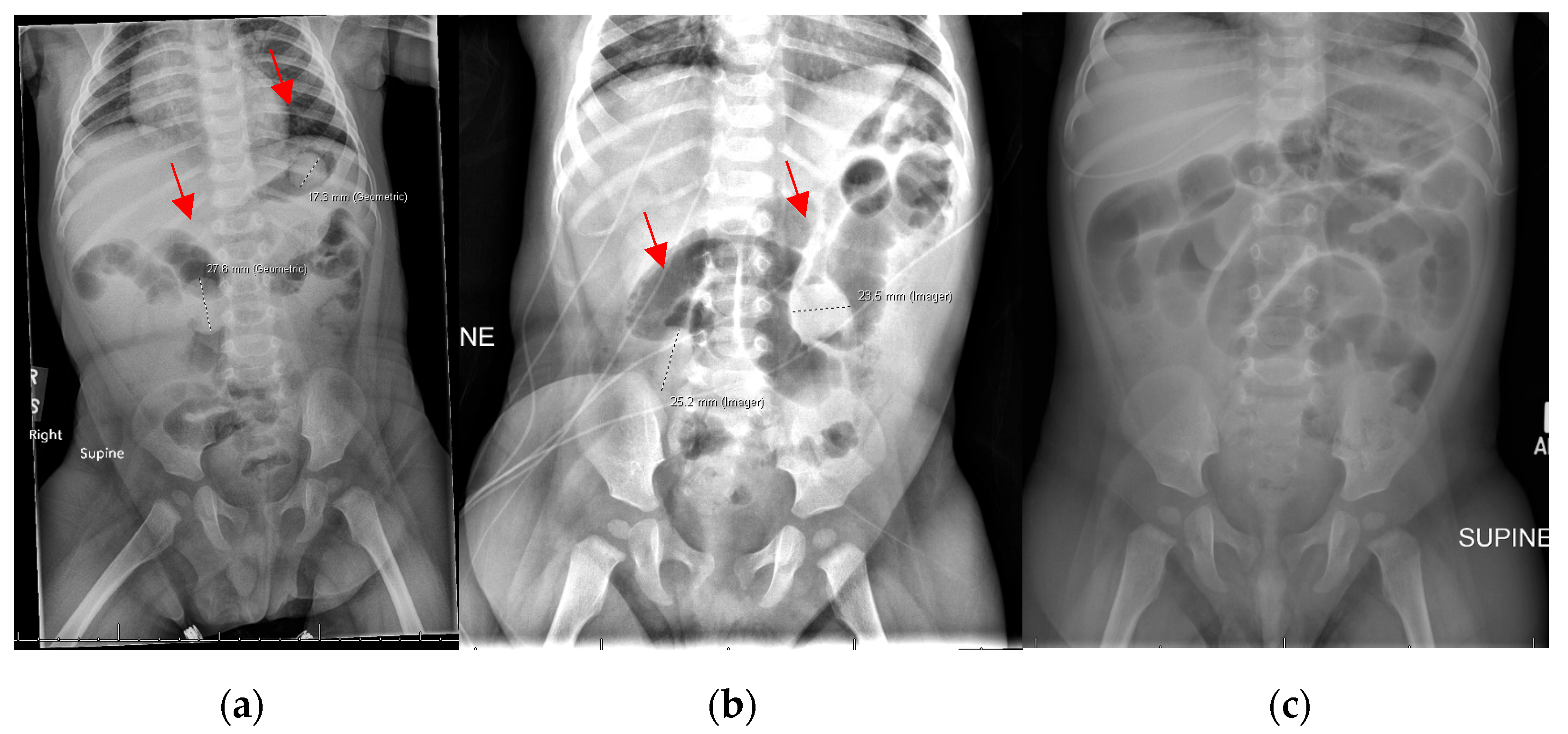

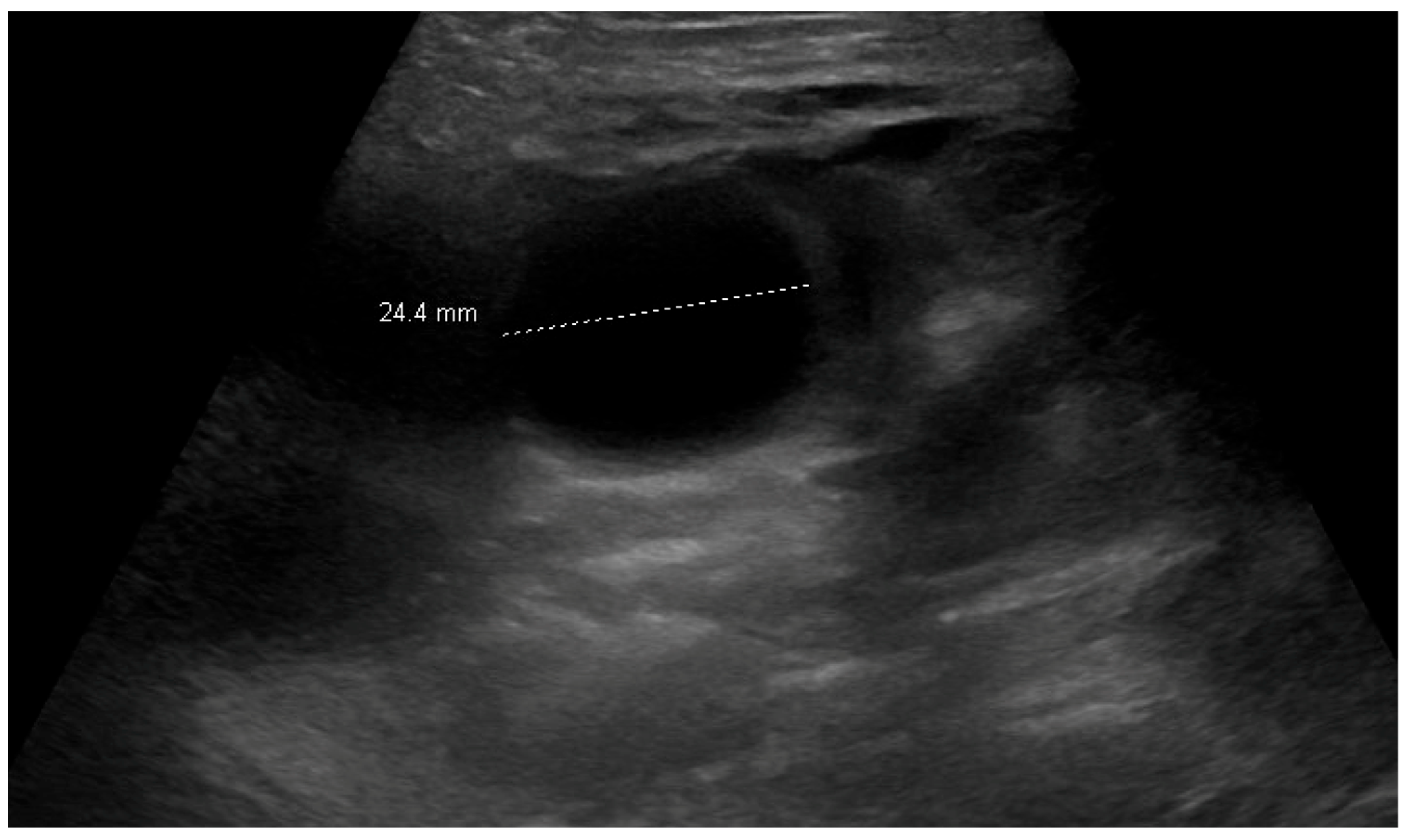

3.1. Patient 1

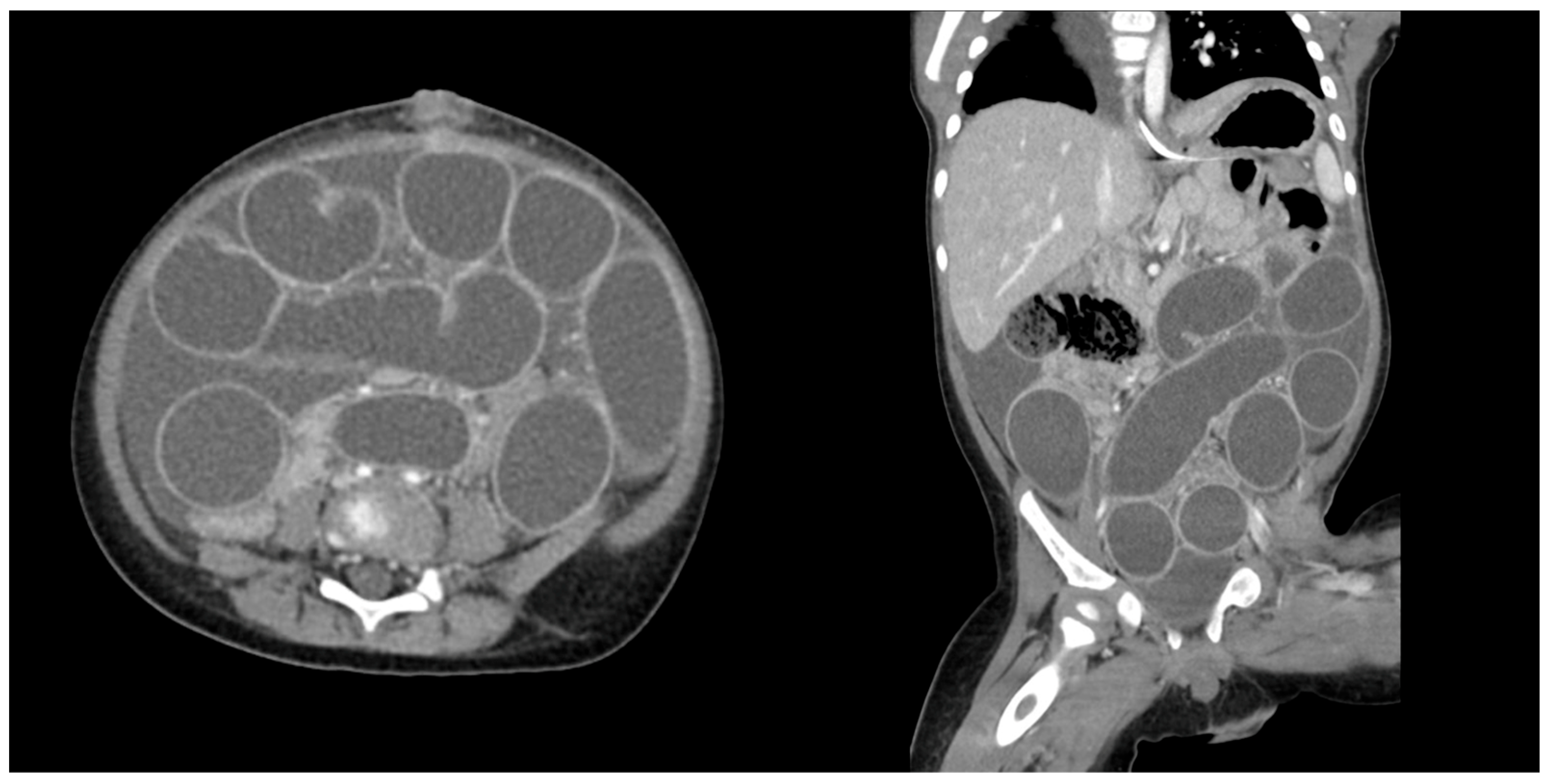

3.2. Patient 2

3.3. Patient 3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NEISS | National Electronic Injury Surveillance System |

References

- Joynes, H.J.; Kistamgari, S.; Casavant, M.J.; Smith, G.A. Pediatric water bead-related visits to United States emergency departments. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 84, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N.; Dabbour, M. Aspiration of superabsorbent polymer beads resulting in focal lung damage: A case report. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; Randell, K.A.; Knapp, J.F. Two Year Old With Water Bead Ingestion. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2015, 31, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalzal, H.G.; Ryan, M.; Reilly, B.; Mudd, P. Managing the Destructive Foreign Body: Water Beads in the Ear (A Case Series) and Literature Review. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2023, 132, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Care, W.; Dufayet, L.; Paret, N.; Manel, J.; Laborde-Casterot, H.; Blanc-Brisset, I.; Langrand, J.; Vodovar, D. Bowel obstruction following ingestion of superabsorbent polymers beads: Literature review. Clin. Toxicol. 2022, 60, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awolaran, O.; Brennan, K.; Yardley, I.; Thakkar, H. Water beads ingestion presenting with repeated bowel obstruction in an infant. BMJ Case Rep. 2024, 17, e257875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darracq, M.A.; Cullen, J.; Rentmeester, L.; Cantrell, F.L.; Ly, B.T. Orbeez: The magic water absorbing bead--risk of pediatric bowel obstruction? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2015, 31, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Are Water Beads Dangerous? Risks & Recall Info. Available online: https://www.today.com/parents/moms/water-bead-mom-warning-rcna73155 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Buffalo Games Recalls Chuckle & Roar Ultimate Water Beads Activity Kits Due to Serious Ingestion, Choking and Obstruction Hazards; One Infant Death Reported; Sold Exclusively at Target. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/Recalls/2023/Buffalo-Games-Recalls-Chuckle-Roar-Ultimate-Water-Beads-Activity-Kits-Due-to-Serious-Ingestion-Choking-and-Obstruction-Hazards-One-Infant-Death-Reported-Sold-Exclusively-at-Target (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Forrester, M.B. Pediatric Orbeez Ingestions Reported to Texas Poison Centers. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2019, 35, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, R.A.; Franchi, T.; Sohrabi, C.; Mathew, G.; Kerwan, A.; SCARE Group. The SCARE 2020 Guideline: Updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2020, 84, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, C.; Bejarano, E.; Siegel, B.; Kovacic, K. Orbeez ingestion: Successful medical management of 1000 absorbent bead ingestion in a 3-year-old patient. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mougey, E.B.; Saunders, M.; Franciosi, J.P.; Gomez-Suarez, R.A. Comparative Effectiveness of Intravenous Azithromycin Versus Erythromycin Stimulating Antroduodenal Motility in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 74, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santucci, N.R.; Chogle, A.; Leiby, A.; Mascarenhas, M.; Borlack, R.E.; Lee, A.; Perez, M.; Russell, A.; Yeh, A.M. Non-pharmacologic approach to pediatric constipation. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 59, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutalib, M.; Kammermeier, J.; Vora, R.; Borrelli, O. Prucalopride in intestinal pseudo obstruction, paediatric experience and systematic review. Acta Gastro-Enterol. Belg. 2021, 84, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Pumiglia, L.; Zhang, B.; Francis, A.; Prey, B.; Ciullo, S.; Horton, J.; Barlow, M. The Itsy-Bitsy Water Bead Went Down the Baby’s Mouth. Will Drinking Gastrografin Help to Flush It Out? J. Surg. Res. 2024, 304, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, J.M.; Dounce, C.; Morelos, A.; Perez, J.; Abebrese, E.; Bergner, C.; Salazar, J.H. Honey, I shrank the beads—Water bead growth and shrinking in different solutions in vitro. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada HC. Water Beads May Pose Life-Threatening Risks to Young Children—Recalls, Advisories and Safety Alerts—Canada.ca. 4 May 2023. Available online: https://recalls-rappels.canada.ca/en/alert-recall/water-beads-may-pose-life-threatening-risks-young-children (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Water Balz|Polymer Balls Recall from Dunecraft—Consumer Reports. Available online: https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2013/05/polymer-balls-raise-alarm/index.htm (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Senators Baldwin, Casey, Collins Introduce ‘Esther’s Law’ to Ban Deadly Water Beads and Protect Kids|U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin. 9 May 2024. Available online: https://www.baldwin.senate.gov/news/press-releases/senators-baldwin-casey-collins-introduce-esthers-law-to-ban-deadly-water-beads-and-protect-kids (accessed on 18 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schuh, J.M.; Olson, H.M.; Leack, K.M.; Kovacic, K.; Maloney, C.; Salazar, J.H. Tiny Beads, Big Problems: Water Bead Ingestions—A Case Series. Children 2025, 12, 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081041

Schuh JM, Olson HM, Leack KM, Kovacic K, Maloney C, Salazar JH. Tiny Beads, Big Problems: Water Bead Ingestions—A Case Series. Children. 2025; 12(8):1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081041

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchuh, Jennifer M., Hannah M. Olson, Kathleen M. Leack, Karlo Kovacic, Caroline Maloney, and Jose H. Salazar. 2025. "Tiny Beads, Big Problems: Water Bead Ingestions—A Case Series" Children 12, no. 8: 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081041

APA StyleSchuh, J. M., Olson, H. M., Leack, K. M., Kovacic, K., Maloney, C., & Salazar, J. H. (2025). Tiny Beads, Big Problems: Water Bead Ingestions—A Case Series. Children, 12(8), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081041