Protease Enzyme Inhibitor Cream for the Prevention of Diaper Dermatitis After Gastrointestinal Surgery in Children: Lessons Learned from a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

Highlights

- Diaper dermatitis occurs in 73.1% of children after gastrointestinal surgery.

- Diaper dermatitis develops within the first two weeks following surgery.

- Diaper dermatitis is a significant clinical issue that requires increased awareness and attention in both research and practice.

- Although no superior preventive strategy was identified, the study offers valuable epidemiological and methodological insights to enhance future investigations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Procedures and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population and Trial Course

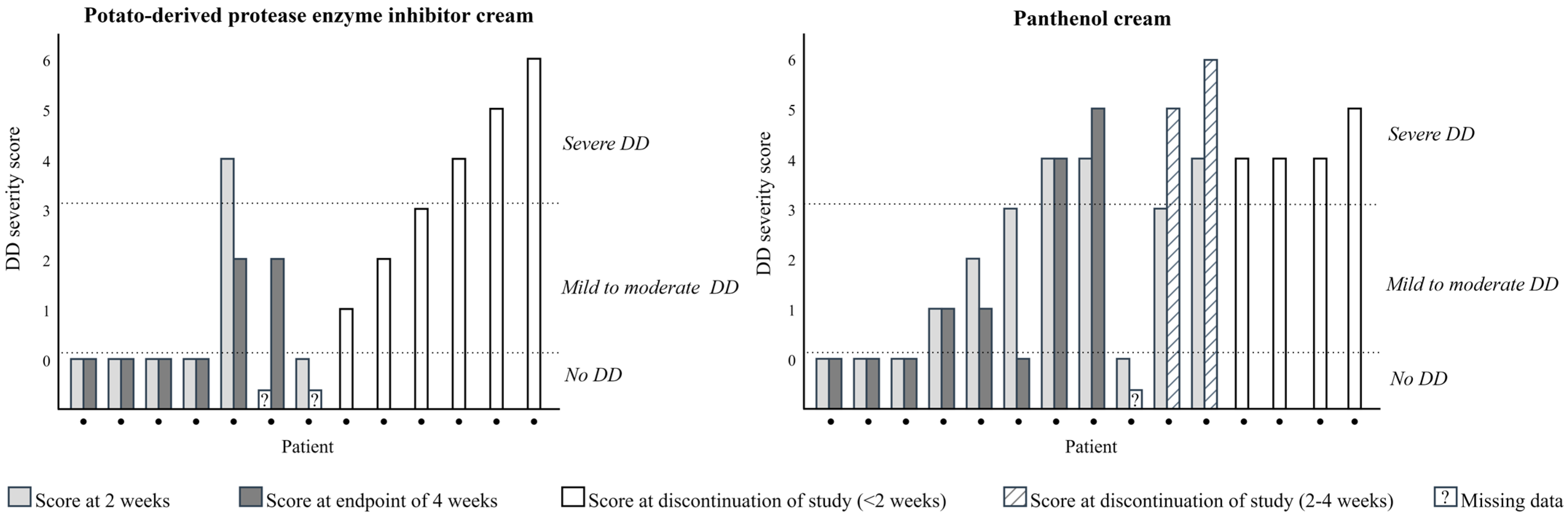

3.2. Diaper Dermatitis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DD | Diaper dermatitis |

| PPEIC | Potato-derived protease enzyme inhibitor cream |

| PC | Panthenol cream |

References

- Ravanfar, P.; Wallace, J.S.; Pace, N.C. Diaper dermatitis: A review and update. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012, 24, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatas, G.N.; Tierney, N.K. Diaper dermatitis: Etiology, manifestations, prevention, and management. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Peytavi, U.; Hauser, M.; Lünnemann, L.; Stamatas, G.N.; Kottner, J.; Garcia Bartels, N. Prevention of diaper dermatitis in infants—A literature review. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeckman, D. A decade of research on Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis (IAD): Evidence, knowledge gaps and next steps. J. Tissue Viability 2017, 26, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.S.L.; Carville, K. Prevention and Management of Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis in the Pediatric Population: An Integrative Review. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2019, 46, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.; Rufener, J.; Klimek, P.; Zachariou, Z.; Boillat, C. Effects of potato-derived protease inhibitors on perianal dermatitis after colon resection for long-segment Hirschsprung’s disease. World J. Pediatr. 2012, 8, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Klunk, C.; Domingues, E.; Wiss, K. An update on diaper dermatitis. Clin. Dermatol. 2014, 32, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruseler-van Embden, J.G.; van Lieshout, L.M.; Smits, S.A.; van Kessel, I.; Laman, J.D. Potato tuber proteins efficiently inhibit human faecal proteolytic activity: Implications for treatment of peri-anal dermatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 34, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruseler-van Embden, J.G.; van Lieshout, L.M. Increased proteolysis and leucine aminopeptidase activity in faeces of patients with Crohn’s disease. Digestion 1988, 40, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouvreau, L.; Gruppen, H.; Piersma, S.R.; van den Broek, L.A.; van Koningsveld, G.A.; Voragen, A.G. Relative abundance and inhibitory distribution of protease inhibitors in potato juice from cv. Elkana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2864–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, B.S.; Mantaring, J.B.; Dofitas, R.B.; Lapitan, M.C.; Monteagudo, A. A New Scale for Assessing the Severity of Uncomplicated Diaper Dermatitis in Infants: Development and Validation. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2016, 33, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi-Sanjani, O.; Kuebler, J.F.; Brendel, J.; Wiesner, S.; Mutanen, A.; Eaton, S.; Domenghino, A.; Clavien, P.A.; Ure, B.M. Implementation and validation of a novel instrument for the grading of unexpected events in paediatric surgery: Clavien-Madadi classification. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, S. Treatment of diaper dermatitis. Dermatol. Clin. 1999, 17, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, A.; Levitt, M.A.; Peña, A. Total colonic aganglionosis: A surgical challenge. How to avoid complications? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2011, 27, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Iacusso, C.; Leonelli, L.; Valfrè, L.; Conforti, A.; Fusaro, F.; Iacobelli, B.D.; Bozza, P.; Morini, F.; Mattioli, G.; Bagolan, P. Minimally Invasive Techniques for Hirschsprung Disease. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2019, 29, 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoshi, A.; Ham, P.B., 3rd; Chen, Z.; Wilding, G.; Vali, K. Timing of the definitive procedure and ileostomy closure for total colonic aganglionosis HD: Systematic review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 2366–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokar, B.; Urer, S. Factors determining the severity of perianal dermatitis after enterostoma closure of pediatric patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; He, Y.B.; Chen, L.; Lin, Y.; Liu, M.K.; Zhou, C.M. Laparoscopic-assisted Soave procedure for Hirschsprung disease: 10-year experience with 106 cases. BMC Surg. 2022, 22, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, D.J. The aetiology and management of irritant diaper dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001, 15 (Suppl. S1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherton, D.J. A review of the pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of irritant diaper dermatitis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004, 20, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Olejnik, A.; Świtek, S.; Bzducha-Wróbel, A.; Kubiak, P.; Kujawska, M.; Lewandowicz, G. Bioactive compounds of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) juice: From industry waste to food and medical applications. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2022, 41, 52–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, N.; Herreman, L.C.M.; Vandooren, J.; Pereira, R.V.S.; Opdenakker, G.; Spelbrink, R.E.J.; Wilbrink, M.H.; Bremer, E.; Gosens, R.; Nawijn, M.C.; et al. Novel high-yield potato protease inhibitor panels block a wide array of proteases involved in viral infection and crucial tissue damage. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 102, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reick, S.; Burckhardt, M.; Palm, R.; Kottner, J. Measurement instruments to evaluate diaper dermatitis in children: Systematic review of measurement properties. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 5813–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PPEIC a (n = 13) | PC b (n = 15) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (66.7) | 0.686 |

| Born prematurely (<37 weeks gestational age), n (%) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (33.3) | 0.686 |

| Small for gestational age (<10th percentile), n (%) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1.000 |

| Age at inclusion in months, median (IQR) | 3.2 (2.2–4.5) | 4.3 (2.3–6.3) | 0.279 |

| Type of surgery and underlying pathology c | |||

| Laparoscopic-assisted pull-through for Hirschsprung’s Disease (no prior ostomy) | 3 | 4 | |

| Ileostomy reversal for Hirschsprung’s Disease | 1 | 2 | |

| Ileostomy reversal and laparoscopic-assisted pull-through for Hirschsprung’s Disease | 1 | 1 | |

| Ileostomy reversal after necrotizing enterocolitis | 2 | 1 | |

| Ileostomy reversal after small bowel atresia | 1 | 2 | |

| Ileostomy reversal after other pathologies d | 3 | 1 | |

| Colostomy reversal after anorectal malformation | 2 | 4 | |

| ≥1 post-operative complications, n (%) | 6 (46.2) | 10 (66.7) | 0.274 |

| Type of postoperative complications, n (Clavien Madadi Classification) | |||

| Cholangitis | - | 1 (II) | |

| Prolonged postoperative ileus | - | 2 (IB/II) | |

| Constipation | 2 (IB) | 2 (IB) | |

| Fever of unknown origin | 2 (IB/II) | 4 (II) | |

| Infection of the ostomy closure wound | - | 3 (IB) | |

| Urinary retention | - | 1 (IIIA) | |

| Edema | - | 1 (IB) | |

| Anastomotic leakage of the ileum | - | 1 (IV) | |

| Persistent diarrhea | 1 (IB) | - | |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 1 (IB) | - | |

| Peripheral intravenous catheter malfunction | 1 (IIIA) | - |

| Included Patients n = 26 a | DD Development n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hirschsprung’s Disease | 12 | 9 (75) |

| Anorectal malformation | 5 | 5 (100) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 3 | 2 (66.7) |

| Small bowel atresia | 3 | 1 (33.3) |

| Other underlying diseases | 3 | 2 (66.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huijgen, D.; Schokker-van Linschoten, I.K.; Versteegh, H.P.; Ruseler-van Embden, J.G.H.; van Lieshout, L.M.C.; Laman, J.D.; Sloots, C.E.J. Protease Enzyme Inhibitor Cream for the Prevention of Diaper Dermatitis After Gastrointestinal Surgery in Children: Lessons Learned from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2025, 12, 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081028

Huijgen D, Schokker-van Linschoten IK, Versteegh HP, Ruseler-van Embden JGH, van Lieshout LMC, Laman JD, Sloots CEJ. Protease Enzyme Inhibitor Cream for the Prevention of Diaper Dermatitis After Gastrointestinal Surgery in Children: Lessons Learned from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Children. 2025; 12(8):1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081028

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuijgen, Demi, Irene K. Schokker-van Linschoten, Hendt P. Versteegh, Johanneke G. H. Ruseler-van Embden, Leo M. C. van Lieshout, Jon D. Laman, and Cornelius E. J. Sloots. 2025. "Protease Enzyme Inhibitor Cream for the Prevention of Diaper Dermatitis After Gastrointestinal Surgery in Children: Lessons Learned from a Randomized Controlled Trial" Children 12, no. 8: 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081028

APA StyleHuijgen, D., Schokker-van Linschoten, I. K., Versteegh, H. P., Ruseler-van Embden, J. G. H., van Lieshout, L. M. C., Laman, J. D., & Sloots, C. E. J. (2025). Protease Enzyme Inhibitor Cream for the Prevention of Diaper Dermatitis After Gastrointestinal Surgery in Children: Lessons Learned from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Children, 12(8), 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081028