Together TO-CARE: A Novel Tool for Measuring Caregiver Involvement and Parental Relational Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Creation and Use of the “Together TO-CARE Template”

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

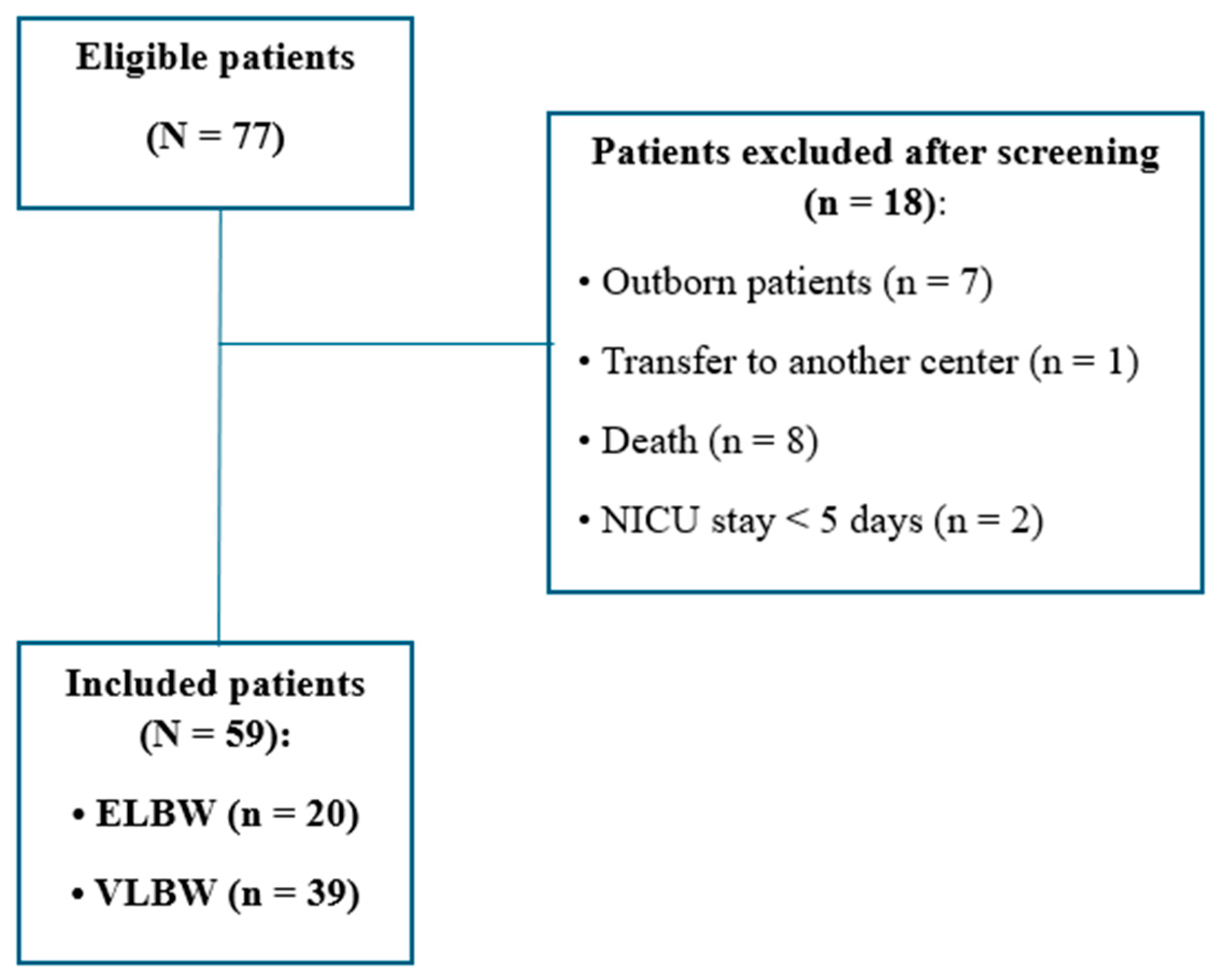

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Compilation Rate

3.3. Caregiver Presence

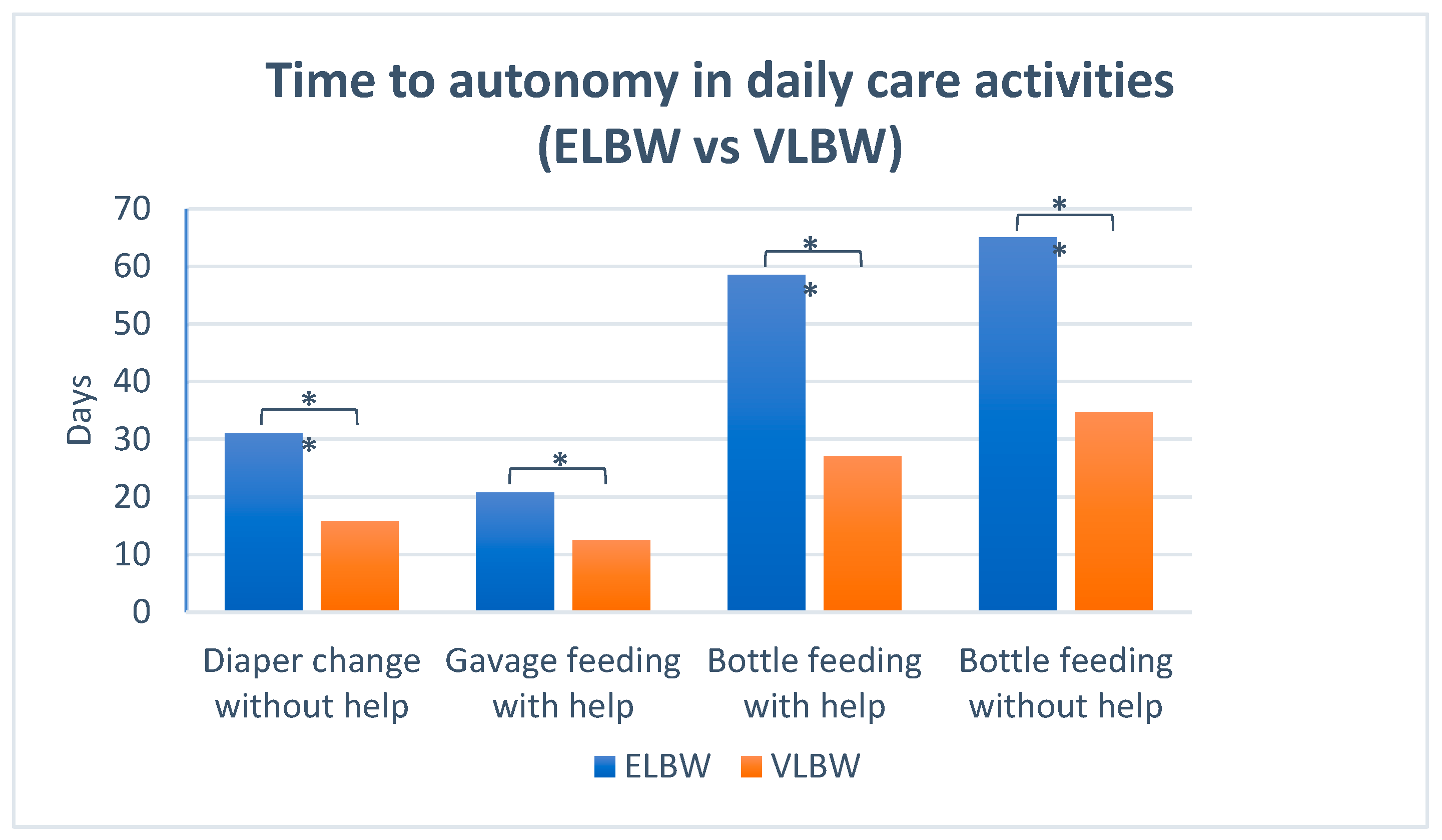

3.4. Caregiver Involvement and Autonomy in Daily Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertoncelli, N.; Lugli, L.; Bedetti, L.; Lucaccioni, L.; Bianchini, A.; Boncompagni, A.; Cipolli, F.; Cosimo, A.C.; Cuomo, G.; Di Giuseppe, M.; et al. Parents’ Experience in an Italian NICU Implementing NIDCAP-Based Care: A Qualitative Study. Children 2022, 9, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guez-Barber, D.; Pilon, B. Parental impact during and after neonatal intensive care admission. Semin. Perinatol. 2024, 48, 151926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Alqahtani, M.; Shaban, M.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Ali, S.I. Impacts of Integrating Family-Centered Care and Developmental Care Principles on Neonatal Neurodevelopmental Outcomes among High-Risk Neonates. Children 2023, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; O’Brien, K. The evolution of family-centered care: From supporting parent-delivered interventions to a model of family integrated care. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCNH—European Standards of Care for Newborn Health. Available online: https://newborn-health-standards.org/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Byrne, E.M.; Hunt, K.; Scala, M. Introducing the i-Rainbow©: An Evidence-Based, Parent-Friendly Care Pathway Designed for Critically Ill Infants in the NICU Setting. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2024, 36, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, L.C.; Duncan, M.M.; Smith, G.C.; Mathur, A.; Neil, J.; Inder, T.; Pineda, R.G. Parental presence and holding in the neonatal intensive care unit and associations with early neurobehavior. J. Perinatol. 2013, 33, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiskila, S.; Axelin, A.; Toome, L.; Caballero, S.; Tandberg, B.S.; Montirosso, R.; Normann, E.; Hallberg, B.; Westrup, B.; Ewald, U.; et al. Parents’ presence and parent-infant closeness in 11 neonatal intensive care units in six European countries vary between and within the countries. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Veenendaal, N.R.; Auxier, J.N.; van der Schoor, S.R.D.; Franck, L.S.; Stelwagen, M.A.; de Groof, F.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Eekhout, I.E.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Axelin, A.; et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the CO-PARTNER tool for collaboration and parent participation in neonatal care. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.M.; Campbell-Yeo, M.; Disher, T.; Dol, J.; Richardson, B.; Chez NICU Home team in alphabetical order; Bishop, T.; Delahunty-Pike, A.; Dorling, J.; Glover, M.; et al. Caregiver Presence and Involvement in a Canadian Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Observational Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugli, L.; Pugliese, M.; Bertoncelli, N.; Bedetti, L.; Agnini, C.; Guidotti, I.; Roversi, M.F.; Della Casa, E.M.; Cavalleri, F.; Todeschini, A.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcome and Neuroimaging of Very Low Birth Weight Infants from an Italian NICU Adopting the Family-Centered Care Model. Children 2023, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.S.; Keskin, Z.; Yavaş, Z.; Özdemir, H.; Tosun, G.; Güner, E.; İzci, A. Developing the Scale of Parental Participation in Care: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Examining the Scale’s Psychometric Properties. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 65, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaro, D.S.; Pelle, C.D.; Buccione, E. Parental participation in care during Neonatal Intensive Care Unit stay: A validation study. Inferm. J. 2022, 1, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncelli, N.; Buttera, M.; Nieddu, E.; Berardi, A.; Lugli, L. The Experience of Caring for a Medically Complex Child in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative Study of Parental Impact. Children 2025, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latour, J.M.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; Hazelzet, J.A.; van Goudoever, J.B. Development and validation of a neonatal intensive care parent satisfaction instrument. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 13, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Oglio, I.; Fiori, M.; Tiozzo, E.; Mascolo, R.; Portanova, A.; Gawronski, O.; Ragni, A.; Amadio, P.; Cocchieri, A.; Fida, R.; et al. Neonatal intensive care parent satisfaction: A multicenter study translating and validating the Italian EMPATHIC-N questionnaire. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, N.M.; Vittner, D.; Samra, H.A.; McGrath, J.M. The PREEMI as a measure of parent engagement in the NICU. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 47, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alle, Y.F.; Akenaw, B.; Seid, S.; Bayable, S.D. Parental satisfaction and its associated factors towards neonatal intensive care unit service: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccione, E.; Scarponcini Fornaro, D.; Pieragostino, D.; Natale, L.; D’Errico, A.; Chiavaroli, V.; Rasero, L.; Bambi, S.; Della Pelle, C.; Di Valerio, S. Parents’ Participation in Care during Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Stay in COVID-19 Era: An Observational Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zores, C.; Gibier, C.; Haumesser, L.; Meyer, N.; Poirot, S.; Briot, C.; Langlet, C.; Dillenseger, L.; Kuhn, P. Evaluation of a new tool—“Step by step with my baby”—To support parental involvement in the care of preterm infants. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 31, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosta, E.; Tomasoni, L.R.; Frusca, T.; Triglia, M.; Pirali, F.; El Hamad, I.; Castelli, F. Preterm delivery risk in migrants in Italy: An observational prospective study. J. Travel Med. 2008, 15, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, G.; Iacovella, C.; Parazzini, F.; Bergamini, V.; Franchi, M. Pregnancy outcome of migrant women delivering in a public institution in northern Italy. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2011, 72, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, G.; Clarkson, G.; Day, M. The Role of the NICU in Father Involvement, Beliefs, and Confidence: A Follow-up Qualitative Study. Adv. Neonatal. Care 2020, 20, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latva, R.; Lehtonen, L.; Salmelin, R.K.; Tamminen, T. Visiting less than every day: A marker for later behavioral problems in Finnish preterm infants. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, R.; Bender, J.; Hall, B.; Shabosky, L.; Annecca, A.; Smith, J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 117, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphorst, K.; Brouwer, A.J.; Poslawsky, I.E.; Ketelaar, M.; Ockhuisen, H.; van den Hoogen, A. Parental Presence and Activities in a Dutch Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Observational Study. J. Perinat. Neonatal. Nurs. 2018, 32, E3–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M.M.; Rossman, B.; Patra, K.; Kratovil, A.; Khan, S.; Meier, P.P. Maternal psychological distress and visitation to the neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, e306–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head Zauche, L.; Zauche, M.S.; Dunlop, A.L.; Williams, B.L. Predictors of Parental Presence in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv. Neonatal. Care 2020, 20, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parental presence |

| If absent: specify reason for absence when known |

| Duration of parental stay (hours) | Insert total hours of parental presence | |

| Contact with the baby |

| If no: specify reason for lack of contact |

| Kangaroo care (KC) |

Breast approach:

| If not performed, select a reason:

|

| Care activities | ||

| Hygiene | Diaper Changing:

Bathing:

| Level of autonomy:

|

| Feeding | Gavage feeding:

| Level of autonomy:

|

| Medication | Drug administration:

| Level of autonomy:

|

| Mean gestational age (weeks) | 29.5 ± 2.5 |

| Weight | |

| Mean birthweight (g) | 1138 ± 282 |

| Mean birthweight (SD) | −0.39 ± 1.03 |

| Small for gestational age | 13/59 (22%) |

| Gender | |

| Girls | 26/59 (44%) |

| Birth type | |

| Singleton | 50/59 (85%) |

| Conception | |

| Spontaneous conception | 47/59 (80%) |

| Delivery type | |

| Vaginal | 9/59 (15%) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparous | 38/59 (64%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 44/59 (75%) |

| Asiatic | 10/59 (17%) |

| African | 5/59 (8%) |

| Language barrier | |

| Yes | 12/57 (21%) |

| Maternal age (years) | 34.5 ± 5.8 |

| 20–29 | 13/58 (22%) |

| 30–39 | 37/58 (64%) |

| Over 40 | 8/58 (14%) |

| Paternal age (years) | 37.3 ± 6.6 |

| 21–29 | 6/57 (11%) |

| 30–39 | 34/57 (60%) |

| Over 40 | 17/57 (29%) |

| Maternal highest level of education | |

| High school or less | 21/59 (36%) |

| College/University | 16/59 (27%) |

| Paternal highest level of education | |

| High school or less | 20/59 (34%) |

| College/University | 15/59 (25%) |

| Maternal employment status | |

| Employed | 40/57 (70%) |

| Paternal employment status | |

| Employed | 55/56 (98%) |

| Distance home–hospital (km) | 19.3 ± 13.5 |

| Length of hospitalization, days | 62.0 ± 35.0 |

| Length of stay in NICU, days | 53.0 ± 38.0 |

| Discharge directly from NICU | 18/59 (30%) |

| Median post-conceptional age at discharge (weeks) | 37.3 (IQR: 36.3–39.3) |

| Weight at discharge | |

| Mean weight at discharge (SD) | −1.27 ± 1.06 |

| Median weight at discharge (g) | 2240 (IQR: 2007–2837) |

| Mean weekly weight gain (g/week) | 148 ± 23 |

| Unadjusted Bivariate Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef β | 95%CI | p | |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 0.18 | −0.83 to 1.19 | 0.72 |

| Birth weight (g) | −0.001 | −0.14 to 0.14 | 0.88 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 0.003 | −0.11 to 0.11 | 0.58 |

| Primiparous | −0.05 | −0.61 to 0.51 | 0.10 |

| Language barrier | 0.009 | −0.10 to 0.10 | 0.85 |

| Maternal age (years) | −0.001 | −0.06 to 0.06 | 0.80 |

| Maternal employment status | 0.05 | −0.03 to 0.13 | 0.26 |

| Distance from hospital (km) | 0.009 | −0.12 to 0.12 | 0.48 |

| Unadjusted Bivariate Model | Adjusted Multivariate Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef β | 95%CI | p | Coef β | 95%CI | p | |

| Primiparous | 0.25 | −0.37 to 0.87 | 0.42 | |||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | −0.02 | −0.14 to 0.1 | 0.76 | |||

| Birth weight (g) | −0.001 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.78 | |||

| Language barrier | −0.89 | −1.53 to −0.25 | <0.01 | −0.18 | −0.91 to 0.54 | 0.62 |

| Maternal age (years) | 0.02 | −0.04 to 0.08 | 0.40 | |||

| Maternal employment status | 1.14 | 0.62–1.66 | <0.01 | 1.12 | 0.43 to 1.81 | 0.002 |

| Distance from hospital (km) | −0.65 | −1.87 to 0.57 | 0.30 | |||

| Activity | First Reported Using TTCT (Days of Life) | First Reported Using TTCT in Corrected Gestational Age (Weeks) |

|---|---|---|

| Diaper change with help | 8.3 ± 7.1 | 30.4 ±2.4 |

| Diaper change without help | 21.1 ± 15.3 | 32.4 ±2.0 |

| Gavage feeding with help | 15.4 ± 9.8 | 31.4 ± 2.4 |

| Bottle feeding with help | 39.5 ± 21.1 | 35 ± 1.3 |

| Bottle feeding without help | 48.0 ± 22.4 | 36 ± 1.5 |

| First KC | 5.4 ± 3.6 | 30.2 ±2.2 |

| First breast approach | 22.7 ± 16.7 | 32.6 ± 1.7 |

| Breastfeeding | 38.4 ± 18.8 | 34.6 ± 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Insalaco, A.; Bertoncelli, N.; Bedetti, L.; Cosimo, A.C.; Boncompagni, A.; Cipolli, F.; Berardi, A.; Lugli, L. Together TO-CARE: A Novel Tool for Measuring Caregiver Involvement and Parental Relational Engagement. Children 2025, 12, 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081007

Insalaco A, Bertoncelli N, Bedetti L, Cosimo AC, Boncompagni A, Cipolli F, Berardi A, Lugli L. Together TO-CARE: A Novel Tool for Measuring Caregiver Involvement and Parental Relational Engagement. Children. 2025; 12(8):1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081007

Chicago/Turabian StyleInsalaco, Anna, Natascia Bertoncelli, Luca Bedetti, Anna Cinzia Cosimo, Alessandra Boncompagni, Federica Cipolli, Alberto Berardi, and Licia Lugli. 2025. "Together TO-CARE: A Novel Tool for Measuring Caregiver Involvement and Parental Relational Engagement" Children 12, no. 8: 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081007

APA StyleInsalaco, A., Bertoncelli, N., Bedetti, L., Cosimo, A. C., Boncompagni, A., Cipolli, F., Berardi, A., & Lugli, L. (2025). Together TO-CARE: A Novel Tool for Measuring Caregiver Involvement and Parental Relational Engagement. Children, 12(8), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081007