Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Parents of Hospitalized Children in 14 Countries

Abstract

Highlights

- In this cohort of 3350 parents from 14 countries, about half reported depression symptoms and over two-thirds reported anxiety symptoms.

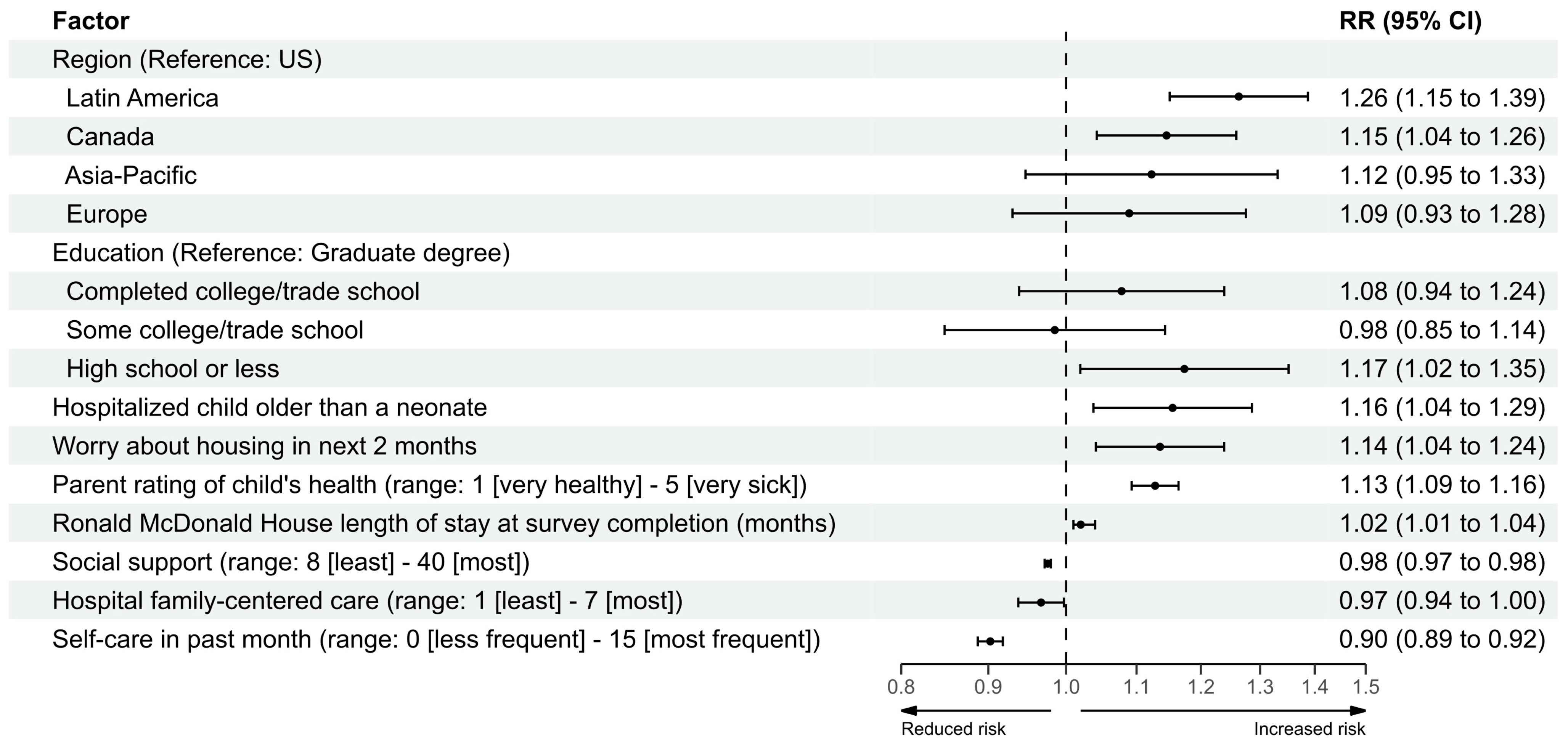

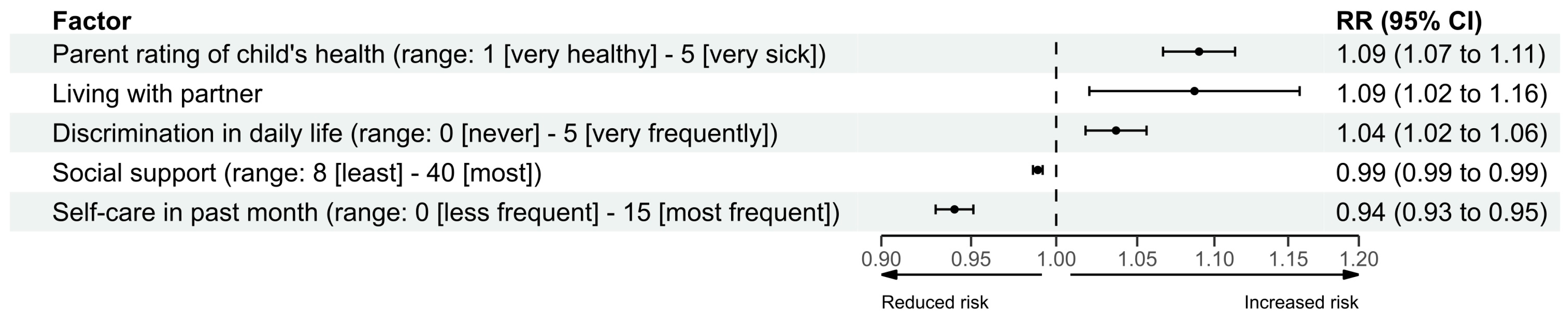

- Poorer rating of their child’s health was associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety symptoms, whereas higher levels of self-care and social support were associated with a reduced risk of depression and anxiety symptoms.

- Depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of hospitalized children are common globally.

- Hospitals should consider routine symptom screening and preventative mental health and support services for parents as part of standard care for hospitalized children.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

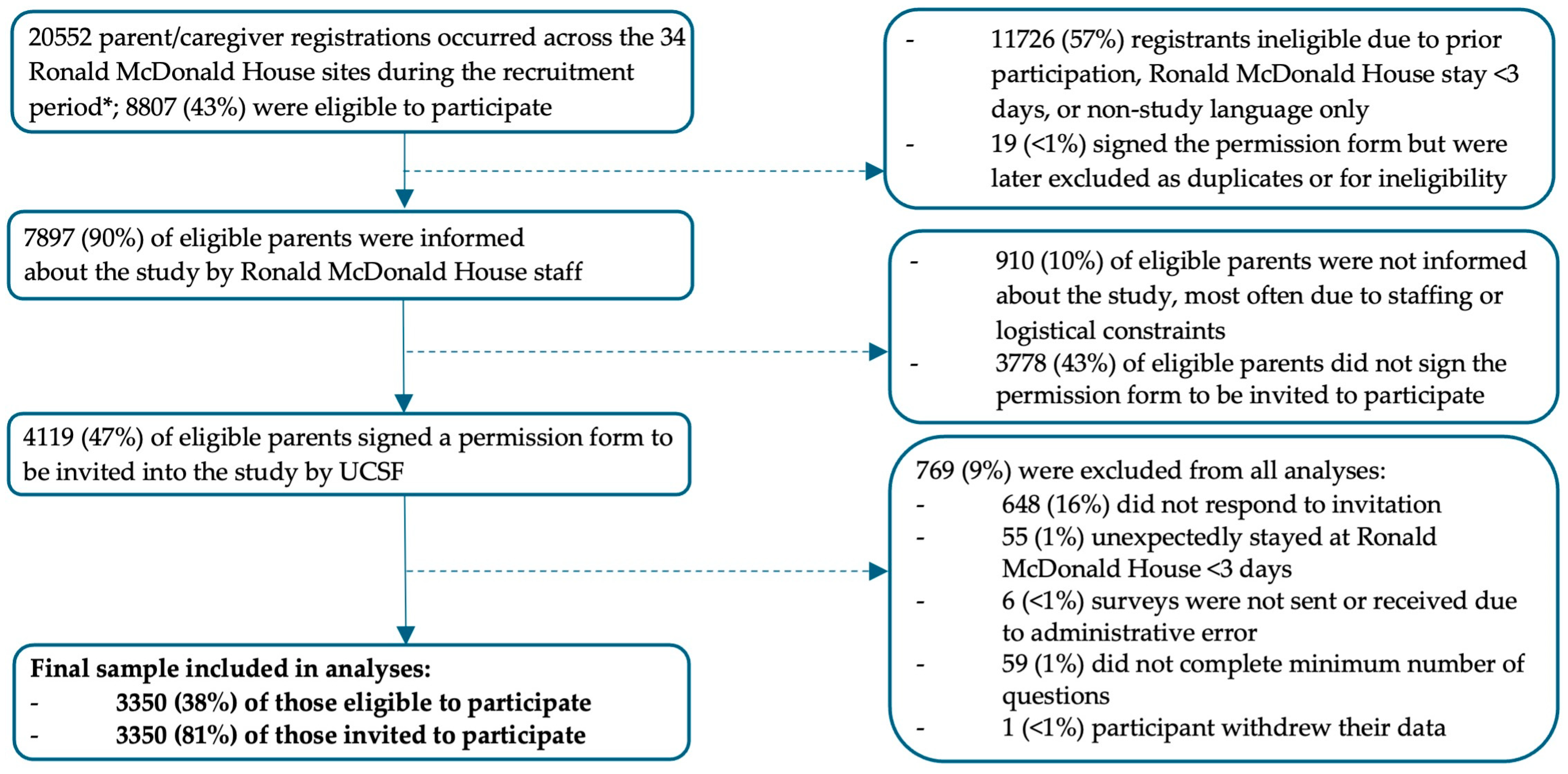

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Primary Outcomes

2.3. Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Parent, Family, and Child Characteristics

3.2. Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms

3.3. Factors Associated with Anxiety Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Drivers of Health

4.2. Child Illness

4.3. Social Support, Basic Self-Care, and Hospital Family-Centered Care

4.4. Strategies to Address the High Prevalence of Parental Depression and Anxiety

4.5. Global Research Gaps

4.6. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RMHC | Ronald McDonald House Charities |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| US | United States |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| AUD | Australian Dollar |

| CAD | Canadian Dollar |

| S/ | Sol |

| JPY | Japanese Yen |

| NT | New Taiwan Dollar |

| RR | Relative risk |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Feudtner, C.; Nye, R.T.; Boyden, J.Y.; Schwartz, K.E.; Korn, E.R.; Dewitt, A.G.; Waldman, A.T.; Schwartz, L.A.; Shen, Y.A.; Manocchia, M.; et al. Association between children with life-threatening conditions and their parents’ and siblings’ mental and physical health. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2137250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.C.; Chorniy, A.; Kwon, S.; Kan, K.; Heard-Garris, N.; Davis, M.M. Children with special health care needs and forgone family employment. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020035378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, L.N.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Lee, Y.; Mahant, S.; Orkin, J.; Marson, A.; Cohen, E. Health outcomes of parents of children with chronic illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2020, 218, 166–177e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.K.; Murtagh, F.E.; Aldridge, J.; Sheldon, T.; Gilbody, S.; Hewitt, C. Health of mothers of children with a life-limiting condition: A comparative cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, E.; Williams, C.; Christofferson, J.; McWhorter, L.G.; Demianczyk, A.C.; Kazak, A.E.; Karpyn, A.; Sood, E. Loss and Grief in Parents of Children Hospitalized for Congenital Heart Disease. Hosp. Pediatr. 2025, 15, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, L.; Dewan, T.; Asaad, L.; Buchanan, F.; Hayden, K.A.; Montgomery, L.; Chang, U. The health and well-being of children with medical complexity and their parents’ when admitted to inpatient care units: A scoping review. J. Child Health Care 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.; Muscara, F.; Anderson, V.A.; McCarthy, M.C. Early traumatic stress responses in parents following a serious illness in their child: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2016, 23, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, G.; Wakefield, C.E.; Ryan, B.; Fleming, C.A.; Levett, N.; Cohn, R.J. Accommodation in pediatric oncology: Parental experiences, preferences and unmet needs. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Wray, J.; Gay, C.; Dearmun, A.K.; Lee, K.; Cooper, B.A. Predictors of parent post-traumatic stress symptoms after child hospitalization on general pediatric wards: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupnik, S.K.; Hill, D.; Palakshappa, D.; Worsley, D.; Bae, H.; Shaik, A.; Qiu, M.; Marsac, M.; Feudtner, C. Parent coping support interventions during acute pediatric hospitalizations: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20164171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, A.J.; Min, J.; Golfenshtein, N.; Marino, B.S.; Curley, M.A.Q.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Perceived family-centered care and post-traumatic stress in parents of infants cared for in the paediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Nurs. Crit. Care 2024, 29, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, C.R.; Mehra, R.; Franck, L.S. Child and family outcomes and experiences related to family-centered care interventions for hospitalized pediatric patients: A systematic review. Children 2024, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, C.R.; Mehra, R.; Franck, L.S. Infant and family outcomes and experiences related to family-centered care interventions in the NICU: A systematic review. Children 2025, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. Patient and Family-Centered Care. Available online: https://www.ipfcc.org/. (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Yakub, N.; Ali, S.; Farid, N.; Shari, N.; Panatik, S. A systematic review comparing pre-post Covid-19 pandemic parenting style and mental health-related factors. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 17, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosquer, M.; Jousselme, C. The experience of parents in Ronald McDonald houses in France. Arch. Pediatr. 2023, 30, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Levis, B.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Krishnan, A.; Neupane, D.; Bhandari, P.M.; Negeri, Z.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression subscale (HADS-D) to screen for major depression: Systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 373, n972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Brahler, E. Normative values for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the general German population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 71, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.C.; Spittle, A.J.; Molesworth, C.M.-L.; Lee, K.J.; Northam, E.A.; Cheong, J.L.Y.; Davis, P.G.; Doyle, L.W.; Treyvaud, K.; Anderson, P.J. Evolution of depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of very preterm infants during the newborn period. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2017). NIMHD Research Framework. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/nimhd-framework.html. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Bell, M.L.; Fairclough, D.L.; Fiero, M.H.; Butow, P.N. Handling missing items in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): A simulation study. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Depressive symptoms in parents of children with chronic health conditions: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Meta-analysis of anxiety in parents of young people with chronic health conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, N.; Hedquist, A.; Dai, D.; Abiona, O.; Bernal-Delgado, E.; Blankart, C.R.; Cartailler, J.; Estupiñán-Romero, F.; Haywood, P.; Or, Z.; et al. International comparison of hospitalizations and emergency department visits related to mental health conditions across high-income countries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, M.; Sheward, R.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.; Coleman, S.M.; Frank, D.A.; Chilton, M.; Black, M.; Heeren, T.; Pasquariello, J.; Casey, P.; et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20172199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.G.; Harris, D.; Coller, R.J.; Chung, P.J.; Rodean, J.; Macy, M.; Linares, D.E. The interwoven nature of medical and social complexity in US children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, A.; González-Hernandez, D.; Fortuny-Falconi, C.M.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Fresan, A.; Nolasco-Rosales, G.A.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; López-Narváez, M.L.; Gonzalez-Castro, T.B.; Chan, Y.M.E. Prevalence and associated factors to depression and anxiety in women with premature babies hospitalized in a neonatal intensive-care unit in a Mexican population. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, e53–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambod, M.; Pasyar, N.; Mazarei, Z.; Soltanian, M. The predictive roles of parental stress and intolerance of uncertainty on psychological well-being of parents with a newborn in neonatal intensive care unit: A hierarchical linear regression analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.P.; Sharma, M.C.; Mohan, R.; Khera, D.; Raghu, V.A. A cross-sectional study to assess the anxiety and coping mechanism among primary caregivers of children admitted in PICU. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 2042–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A.; Vu, C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54 (Suppl. 2), 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Narcisse, M.R. Discrimination, depression, and anxiety among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e252404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremler, R.; Haddad, S.; Pullenayegum, E.; Parshuram, C. Psychological outcomes in parents of critically ill hospitalized children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 34, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lin, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yuan, L. Interventions and strategies to improve social support for caregivers of children with chronic diseases: An umbrella review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 973012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, C.; Manne, S.; DuHamel, K.; Austin, J.; Ostroff, J.; Boulad, F.; Parsons, S.K.; Martini, R.; Williams, S.E.; Mee, L.; et al. Social support from family and friends as a buffer of low spousal support among mothers of critically ill children: A multilevel modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C.; Stawnychy, M.A.; Matus, A.; Hirschman, K.B. Does self-care improve coping or does coping improve self-care? A structural equation modeling study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2024, 78, 151810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Anglin, D.M.; Colman, I.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Jones, P.B.; Patalay, P.; Pitman, A.; Soneson, E.; Steare, T.; Wright, T.; et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: Evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramszlo, C.; Karpyn, A.; Demianczyk, A.C.; Shillingford, A.; Riegel, E.; Kazak, A.E.; Sood, E. Parent perspectives on family-based psychosocial interventions for congenital heart disease. J. Pediatr. 2020, 216, 51–57e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Initiative to Support Parents. Inter-Agency Vision. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-initiative-to-support-parents (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Scheidecker, G.; Tekola, B.; Rasheed, M.; Oppong, S.; Mezzenzana, F.; Keller, H.; Chaudhary, N. Ending epistemic exclusion: Toward a truly global science and practice of early childhood development. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2024, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwemedimo, O.T.; May, H. Disparities in Utilization of Social Determinants of Health Referrals Among Children in Immigrant Families. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epino, H.M.; Rich, M.L.; Kaigamba, F.; Hakizamungu, M.; Socci, A.R.; Bagiruwigize, E.; Franke, M.F. Reliability and construct validity of three health-related self-report scales in HIV-positive adults in rural Rwanda. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, W.E.; Gehlbach, S.H.; De Gruy, F.V.; Kaplan, B.H. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Med. Care 1988, 26, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc. Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, and the Oregon Primary Care Association. PRAPARE® Screening Tool. Available online: https://prapare.org/the-prapare-screening-tool/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Lisanti, A.J.; Demianczyk, A.C.; Costarino, A.; Vogiatzi, M.G.; Hoffman, R.; Quinn, R.; Chittams, J.L.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Skin-to-Skin Care is associated with reduced stress, anxiety, and salivary cortisol and improved attachment for mothers of infants with critical congenital heart disease. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 50, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Separation and Closeness Experiences in Neonatal Environment (SCENE) Research Group. Parent and nurse perceptions on the quality of family-centred care in 11 European NICUs. Aust. Crit. Care 2016, 29, 201–209, Correction in Aust. Crit. Care 2017, 30, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Franck, L.S.; Shellhaas, R.A.; Lemmon, M.E.; Sturza, J.; Barnes, M.; Brogi, T.; Hill, E.; Moline, K.; Soul, J.S.; Chang, T.; et al. Parent Mental Health and Family Coping over Two Years after the Birth of a Child with Acute Neonatal Seizures. Children 2021, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Soft. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, A.P.; De Livera, A.M.; Lee, K.J.; Moreno-Betancur, M.; Simpson, J.A. Multiple imputation methods for handling missing values in longitudinal studies with sampling weights: Comparison of methods implemented in Stata. Biom. J. 2020, 63, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliant, R.; Dever, J.; Kreuter, F. Practical Tools for Designing and Weighting Survey Samples, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Center For Education Statistics. NAEP Weighting Procedures: 2003 Weighting Procedures and Variance Estimation. Tech. Rep. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/tdw/weighting/2002_2003/weighting_2003.aspx (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Lumley, T. Analysis of Complex Survey Samples. J. Stat. Softw. 2004, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; White, I.R.; Royston, P. How should variable selection be performed with multiply imputed data? Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 3227–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.G. Simultaneous Statistical Inference; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic (Unweighted n) | Unweighted n | Weighted Percent, Unless Otherwise Noted a |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Characteristics and Social Drivers of Health | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 3256 | 35.0 (29.0, 42.0) |

| Parental role (n = 3341) | ||

| Mother | 2594 | 78.6% |

| Father | 616 | 18.1% |

| Other | 131 | 3.3% |

| Education (n = 3328) | ||

| High school or less | 1436 | 35.3% |

| Some college/trade school | 560 | 22.6% |

| Completed college/trade school | 1014 | 29.9% |

| Graduate degree | 318 | 12.2% |

| Living with partner (n = 3324) | 2511 | 76.3% |

| Discrimination in daily life, median (IQR) b | 3312 | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) |

| Frequency of basic self-care in the past month, mean (SD) c | 3300 | 5.9 (2.9) |

| Social support, median (IQR) d | 3279 | 34.0 (27.0, 39.0) |

| Family Characteristics | ||

| Low household income (n = 2733) e | 1380 | 46.6% |

| One or more unmet basic needs (n = 3190) | 1396 | 34.8% |

| Worry about housing in the next 2 months (n = 3280) | 834 | 17.0% |

| Child Characteristics | ||

| Child’s age (years), median (IQR) | 3088 | 3.0 (0.1, 11.0) |

| Child’s sex or gender (n = 3265) | ||

| Male | 1759 | 54.0% |

| Female | 1470 | 44.8% |

| Other | 36 | 1.2% |

| Having 1 or more chronic health concerns or disabilities (n = 3172) | 1743 | 57.2% |

| Most common reasons for child’s hospital treatment (n = 3303) | ||

| Cardiology | 846 | 24.3% |

| Neonatal | 679 | 23.1% |

| Oncology/Hematology | 750 | 20.9% |

| Parent rating of child’s current health, median (IQR) f | 3027 | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) |

| Parental Healthcare Experiences | ||

| Ronald McDonald House length of stay at the time of survey (months), median (IQR) | 3292 | 0.1 (0.07, 0.3) |

| Travel time between the family’s home and the hospital ≥2 h each way (n = 3299) | 2251 | 70.5% |

| Time spent with the child in hospital ≥7 h per day (n = 3152) | 2452 | 82.2% |

| Hospital family-centered care, mean (SD) g | 3162 | 6.2 (1.0) |

| Outcome (Unweighted n) | Unweighted N | Weighted Percent |

|---|---|---|

| HADS depression (n = 3304) | ||

| Clinically significant or concerning symptoms | 1789 | 49.7% |

| No clinically significant or concerning symptoms | 1515 | 50.3% |

| HADS anxiety (n = 3304) | ||

| Clinically significant or concerning symptoms | 2286 | 69.0% |

| No clinically significant or concerning symptoms | 1018 | 31.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franck, L.S.; Mehra, R.; Hodgson, C.R.; Gay, C.; Rienks, J.; Lisanti, A.J.; Pavlik, M.; Manju, S.; Turaga, N.; Clay, M.; et al. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Parents of Hospitalized Children in 14 Countries. Children 2025, 12, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081001

Franck LS, Mehra R, Hodgson CR, Gay C, Rienks J, Lisanti AJ, Pavlik M, Manju S, Turaga N, Clay M, et al. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Parents of Hospitalized Children in 14 Countries. Children. 2025; 12(8):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081001

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranck, Linda S., Renée Mehra, Christine R. Hodgson, Caryl Gay, Jennifer Rienks, Amy Jo Lisanti, Michelle Pavlik, Sufiya Manju, Nitya Turaga, Michael Clay, and et al. 2025. "Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Parents of Hospitalized Children in 14 Countries" Children 12, no. 8: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081001

APA StyleFranck, L. S., Mehra, R., Hodgson, C. R., Gay, C., Rienks, J., Lisanti, A. J., Pavlik, M., Manju, S., Turaga, N., Clay, M., & Hoffmann, T. J. (2025). Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Parents of Hospitalized Children in 14 Countries. Children, 12(8), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081001