1. Introduction

Among the most vulnerable children and young people in our society are those with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) [

1]. SEND is a term within an English context which reflects the fact that children with a special educational need (SEN) may also possess a disability, and therefore fall within the legal ambit of the additional protections afforded by the Equality Act 2010 [

2]. Under section 20(1) of the Children and Families Act 2014 (CFA) [

3], a child or young person “has special educational needs if he or she has a learning difficulty or disability which calls for special educational provision to be made for him or her”, while section 20(2) proceeds to state that such a difficulty or disability means they have “a significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of others of the same age” or that the disability “prevents or hinders him or her from making use of facilities of a kind generally provided for others of the same age in mainstream schools or mainstream post-16 institutions”. Children and young people with SEND are entitled to provision to be made for them in school through ‘SEN Support’. If a child or young person with SEND requires more provision than is available through SEN support, an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) can be obtained through the process of an Education, Health and Care Needs assessment. The purpose of an EHCP, which should be holistic and person-centred [

4,

5], is “to meet the special educational needs of the child or young person, to secure the best possible outcomes for them across education, health and social care and, as they get older, prepare them for adulthood” [

6] (p. 142).

In comparison to their peers without SEND, children with SEND are more likely to qualify for free school meals [

7] and be exposed to poverty [

8]. Education, health, and social care provision for children with SEND in the UK has experienced chronic underfunding by an estimated £1.5bn [

9,

10], and has been described as severely flawed and inequitable [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the process for obtaining SEND support has been characterised by “confusion and at times unlawful practice, bureaucratic nightmares, buck-passing, and a lack of accountability, strained resources and adversarial experiences” [

14] (p. 3).

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2, leading to COVID-19, exacerbated many of these difficulties. The declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation in March 2020 prompted a series of measures by the UK Government to curb transmission, including directives such as working from home (where possible), the closure of certain businesses and venues, restrictions on public gatherings, and advice on handwashing and respiratory hygiene [

15]. Redeployment of healthcare staff to COVID-19 related duties also took place and schools closed to all pupils except those of key workers and children categorised as vulnerable. One of the first legislative changes enacted under the Coronavirus Act 2020 concerned the formal diminution of the legal standard contained in section 42 of the CFA (2014), which places an ‘absolute duty’ on Local Authorities (LAs) to meet the education and health care needs of children and young people with SEND. This was replaced by a ‘reasonable endeavours’ duty, which in England was enacted without the benefit of a children’s rights impact assessment. From 6th January 2021 until 29th March 2021, a second national lockdown occurred, during which time children and young people were again mandated to engage in learning and education from home whenever possible. During the lockdowns, children and young people with an EHCP were considered ‘vulnerable’ by the UK Government and should have been able to continue attending school in-person, whereas children in receipt of SEN support only were not. Therefore, a significant number of children with SEND (1.1 million) in receipt of SEN support did not have the opportunity to continue attending school in-person [

16].

Evidence indicates that the education of children with SEND was adversely affected by the pandemic [

1,

13,

17]. For instance, the ‘Ask Listen Act’ Study [

18] found that 69% (n = 509) of parents/carers thought that the national lockdowns had a negative impact on their child’s education and learning, and 89% (n = 655) reported that their child was not able to access face-to-face education during the pandemic. Likewise, other studies show that between March 2020 and February 2021, of 3487 families surveyed, only 30% of children with SEND continued attending school [

19] and only 6% of children with EHCPs went to school between March and May 2020 [

20]. Moreover, remote learning was reported as not working well for most children with SEND [

11,

21], with parents noting that it was not effective in meeting their child’s needs [

18]. For many children, there was no individualised support, work was not differentiated, online lessons were not adapted, and minimum adjustments were denied [

17,

21,

22].

Health and social care support for children with SEND and their families was also hugely affected and reported as insufficient, with many essential appointments and assessments being delayed, rescheduled, or cancelled [

18,

19,

21,

23,

24]. In 2021, 64% of parents reported receiving a decreased level of health and social care support (including from educational psychologists [EPs], occupational therapists [OTs], speech and language therapists [SALTs], and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services [CAMHS]) for their child and, as a result, over half of parents (68%) stated that their child’s physical health declined [

25]. Further studies suggested that many children with SEND’s mental health and wellbeing also deteriorated during the pandemic [

10,

13,

18,

19,

21].

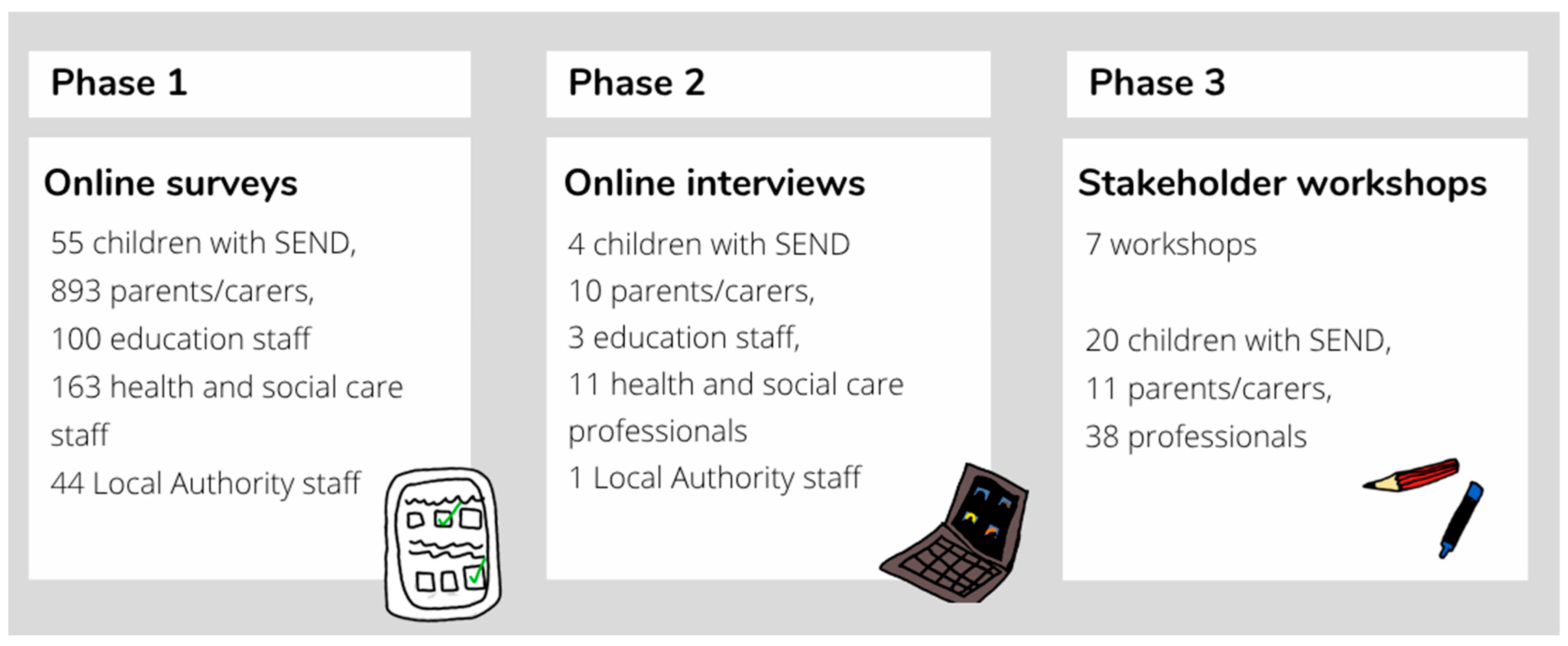

However, despite existing evidence pointing towards a disproportionate negative impact of the pandemic on children and young people with SEND, there has been a noticeable lack of solution-focused research exploring strategies and priorities to support this demographic in the post-pandemic landscape. This paper outlines the collaborative process of identifying priorities for policy and practice, aimed at ameliorating the enduring consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with SEND, employing a rights-based approach. This multi-phase, multi-stakeholder consensus-building study consisted of mixed-method online surveys (Phase 1), semi-structured qualitative interviews (Phase 2), and activity-based group workshops (Phase 3), dedicated to establishing priorities for children with SEND, encompassing those receiving both SEN support as well as those with an EHCP.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

In total, 893 parents/carers, 55 children with SEND, and 307 professionals (163 health and social care, 100 education, 44 Local Authority) completed the survey. Children were aged 5–16 (mean = 11.3 years) and 93% (n = 48) were White British or Irish. Overall, 55% (n = 29) identified as male and 40% (n = 21) identified as female; the remainder chose not to say. They were predominantly based across England, although a minority of participants were also located in Scotland (6%; n = 3) and Wales (1%; n = 2). In terms of support needs, 60% (n = 32) had a communication and interaction need (e.g., autism, 57% (n = 30) had a cognition and learning need (e.g., learning difficulties), 42% (n = 22) had social, emotional and mental health difficulties (e.g., anxiety disorder) and 23% (n = 12) had sensory and/or physical needs (e.g., cystic fibrosis). Regarding parents/carers, 88% (n = 799) were White British or Irish. The majority (96%; n = 848) identified themselves as female, 4% (n = 37) were male, and 0.2% (n = 2) chose ‘not to say’. In terms of their children, 67% (n = 600) reported that their child had communication and interaction needs, 52% (n = 465) had cognition and learning needs, 42% (n = 379) had social, emotional and mental health difficulties, and 34% (n = 306) had sensory and/or physical needs (parents could tick as many boxes as applied). Regarding schooling, 58% (n = 519) of parents/carers reported that their children attended mainstream school, 25% (n = 224) were in a special school, 1% (n = 8) were in a pupil referral unit or alternative provision, 4% (n = 33) were home educated or flexi-schooling, 3% (n = 22) were in a private or independent school, and 0.1% (n = 1) were in a residential school. Finally, professionals were predominantly based across England, although a small number of participants were located in Wales (1%; n = 4). Professionals’ job roles included social care (8%; n = 24) or SEND-specific social care (7%; n = 23), community primary care (17%; n = 53) or SEND-specific primary care (11%; n = 33), school teacher (9%; n = 28), teaching assistants (7%; n = 22), school leadership (9%; n = 28), and school SEND coordinators (SENDCos) (14%; n = 44).

Ten parents/carers, four children and young people, and 15 professionals participated in semi-structured interviews. Children aged 8–14, all male, with SEND including autism, ADHD, sensory differences, specific learning difficulties (SpLDs) and mental health needs took part in an interview. Parents were all female, and had children with SEND including autism, ADHD, sensory needs, mental health needs, genetic conditions and SpLDs. The professionals’ job roles included Educational Psychologist, school SEND coordinators (primary and secondary), Deputy Headteacher in a special school, Family and Specialist Support Service Manager, Community Physiotherapist, Designated Clinical Officer, Therapy Manager, and Local Authority Youth Voice Lead.

In total, 11 parent/carers, 20 children with SEND, and 38 professionals participated in the activity-based group workshops. No demographic information was formally collected, although children and young people with a range of support needs were involved, including ADHD, autism, learning disabilities, sensory impairments, and physical disabilities. Professionals’ job roles included Head of SEND, SEND advisor, and SEND consultant at local councils, paediatrician, advanced nurse practitioner, learning disability specialist in CAMHS, early years worker, and children’s holiday club worker.

We will firstly present the priorities identified by each participant group from the surveys and interviews, and then describe how these were refined and consensus was reached within the workshops.

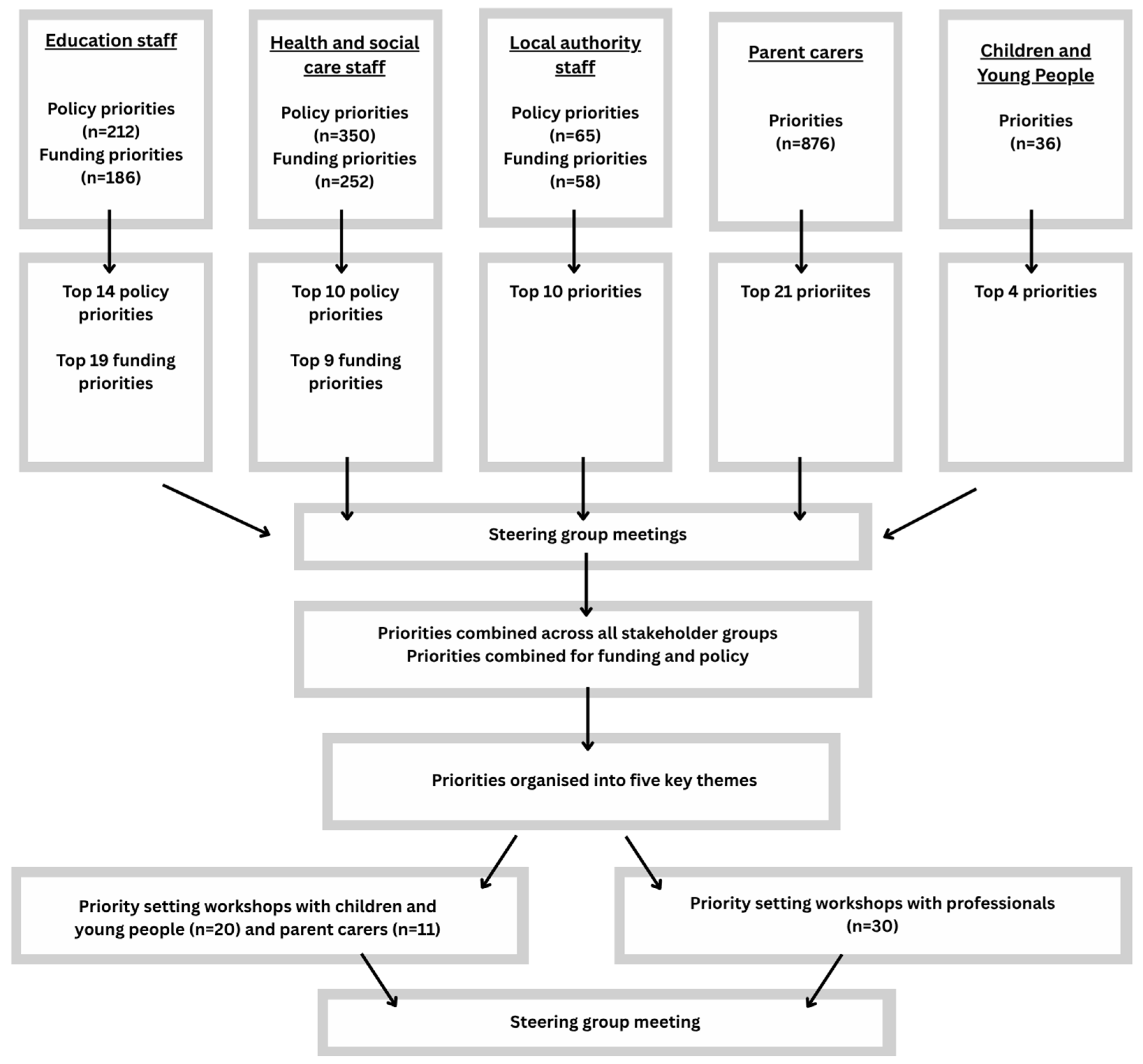

Figure 2 outlines the processes undertaken at each Phase.

3.2. Surveys and Interviews

36 priorities were identified from children and young people’s (n = 55) survey responses, which were grouped into three areas of education, friends, and mental health. 876 priorities were identified from the parents/carers’ (n = 893) surveys; these were tallied before being collated into the ‘top twenty’ priorities. For the education professionals, 212 policy priorities and 186 funding priorities were identified (n = 100); these were collated and tallied into the top 14 policy priorities, and 24 top funding priorities (many had an equal number of tallies). Health and social care professionals (n = 163) identified 350 policy priorities and 252 funding priorities across the survey responses; these were analysed and refined into the top ten policy priorities, and top nine funding priorities. Local Authority staff (n = 44) identified 147 policy priorities and 27 specific funding priorities; these were refined and analysed to the ‘top ten’ policy and funding priorities (as there was significant overlap between them). Interview data were then mapped onto the relevant priorities, to provide further context and rationale for each, whilst remaining open for any priorities not previously identified to be added. No new priorities were identified from the interview data alone. The priorities for each stakeholder group are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.3. Workshops

Prior to the workshops, the priority areas for each stakeholder group (

Table 1 and

Table 2) were synthesised to remove duplicates, and merged and grouped together to encompass priorities from all the stakeholder groups. These broad priority areas were organised into five key areas: (1) opportunities to socialize and have fun, (2) support for social, emotional and mental health, (3) flexibility, choice and support in school, (4) access to services and therapies to stay healthy, and (5) support for parents/carers and family (see

Supplementary Materials Figure S1 for an overview). Priorities within each of the areas were then presented in turn at each workshop, asking participants to sort, refine and organise the priorities, and to identify if any priorities were missing.

3.4. Children’s Activity-Based Group Workshops

The children in the workshops discussed the priority areas from their perspectives and identified additional priorities within these. Many of the children told us that their mental health had deteriorated during the lockdowns, resulting in them feeling sad, lonely, and anxious. To counter this, children and young people suggested that increased funding for mental health services was a priority following the pandemic. Additionally, they explained that they would like the school environment to be one where they feel they can ‘belong’, which helps them want to attend school and enables them to ‘

feel safe in school’. The children who continued to attend school in-person over the lockdowns explained that they had a better experience at school during these times, as there was more one-to-one help to complete schoolwork and ‘

school was quieter and better’. In terms of lessons, children would like more variation, ‘

to learn skills to get a job’ and for ‘

lessons to be more fun’, for example, being able to go swimming, do more physical education, and play more games. Outside of school, children would like to have ‘

places to have fun and be with friends’, make new friends, and participate in activities. The pictures in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 provide examples of what children told us through the workshop activities.

3.5. Parents/Carers’ Activity-Based Group Workshops

Many of the comments in the workshops related to ‘everything being reactive not proactive; only giving help once in crisis—only once a family is in breakdown’ and how the SEND system forced parents ‘to focus on what is wrong with my child rather than their strengths’. Parents/carers told us that they felt the pandemic had a detrimental effect on their child’s mental health, and that more mental health provision is needed for children with SEND, so that they can discuss their feelings and receive support, to prevent a mental health crisis from occurring. Parents/carers felt that in order for this to be effective, mental health professionals need a better understanding of SEND and offer alternatives to talking therapies, including ‘more fun options such as walks, nature or games’. It was also identified that it can take longer for children with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs to build trust with professionals and ‘by the time the child starts opening up in counselling then the block is over’. In terms of education and learning, the transition back to school was overwhelming for many children with SEND, and parents/carers felt that more time and space to catch up socially would have been helpful for their children when returning to school. Parents/carers also felt it would have been beneficial for schools to provide their children with more opportunities to develop their independence and life skills, and pursue their special interests, rather than exclusively focusing on catching up with the curriculum. Additionally, parents/carers felt it was important for mainstream schools to have more SEND trained staff, and for them be more inclusive.

With regard to health and social care, while some parents/carers did note that professionals delivered excellent care during the lockdowns, going ‘above and beyond’, most parents/carers said that health and social care and respite provision was unavailable. Parents/carers said that they would have welcomed a regular ‘check in’ phone call from professionals during this time. However, parents/carers also said that while phone consultations and online meetings were helpful for some children with SEND, they were difficult for others, and, as such, suggested that children could be given the option of a face-to-face or online sessions for future appointments. Parents/carers also highlighted the lengthy delays and many obstacles they faced when trying to access specialists to obtain diagnoses, treatment, or therapy. Parents/carers prioritised the need to reduce waiting lists and the lack of support along the journey; ‘you have to fight for anything’, and also afterwards; ‘you get the diagnosis and don’t get offered anything’.

Parents/carers explained how they felt overwhelmed and exhausted having to ‘fight for any kind of support’ for their child and navigate the SEND system. Many parents discussed how advocates to guide families through the process of obtaining support were invaluable but often non-existent; ‘you need someone who gives advice on options, where to go, who to speak to for support and help with forms’. They also discussed the survey and interview findings which highlighted a lack of local places for children with SEND to socialise, have fun without judgement, and feel part of the community. These elements were highlighted as a ‘lifeline’ for both parents/carers and their children, but often were described as oversubscribed; ‘they shouldn’t have to wait 2 years to go to the cinema’.

3.6. Professionals’ Group Workshops

The workshops highlighted examples where professionals had worked ‘over and above’ their role during the pandemic to navigate around restrictions and deliver services to children with SEND and their families. However, professionals also reported that the entire workforce (across education, health, social care, and government) needed improved trained on SEND-related issues as ‘teachers, TAs, senior leaders, do not have enough experience and knowledge to put enough intervention and support in for children with SEND’, and particularly around the link between mental health difficulties and disability to ‘make sure no diagnostic overshadowing is going on’. They spoke about how a graduated response to mental health support was needed, from specialists who can support a child in crisis to lower-intensity wellbeing support in school. They also felt as a whole the education system needed changing to prioritise and promote children’s mental health; ‘I do not feel that the education system as it is now is fit for purpose, I don’t think it’s helpful to any young person’s mental health’. Professionals commented that following the pandemic, schools should focus on the wellbeing of children rather than ‘catching up’ on education and learning. According to professionals, remote learning worked well for a minority of children with SEND due to a lack of inclusivity in the school setting and therefore felt that ‘schools should also consider that there should continue to be an online offer because a lot of our young people thrived in lockdown because they didn’t have to be in that environment’. Conversely, they also spoke about how some children with SEND were home-schooled ‘not because it was chosen, but because they couldn’t cope going to school’, thus highlighting that schools need to become more inclusive. Furthermore, professionals felt that community inclusion was important for children with SEND, and strategies for this should be integrated into EHCPs.

Professionals highlighted how they saw parents/carers who were exhausted and ‘stressed out’ during the pandemic, as social care support, such as respite services, ceased, and emphasised a need for ‘holiday activity settings with specialised provisions that can cater for mixed abilities and accessible provision’. They also commented on a significant increase in requests for SEND support, which they could not meet due to a lack of funding and resources. As a result, professionals felt that existing challenges with service delivery had been amplified, but their services remained understaffed as no new staff were coming entering the workforce; ‘we have a recruitment and retention problem and heads reporting that they are unable to recruit to positions’. As a result, professionals suggested that greater opportunities to train more healthcare workers (especially speech and language therapists) were needed.

3.7. Priorities for Policy and Practice for Children with SEND

Developed through iterative consultation and collaborative decision-making, the priorities identified from Phases 1 and 2 were organised and synthesised into five key areas, before being further refined during Phase 3. The full set of priorities for policy and practice, including responsible organisations and links to children’s rights (in accordance with the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC; [

36]) are included in

Supplementary Materials Table S1. However,

Table 3 provides a summary of key priorities.

The priorities were grounded in a child-centred approach and aligned with the rights of children as outlined in the UN CRC [

36]. They are applicable to all children and young people aged 5–16 with SEND. Whilst these priorities for policy and practice have been framed by the rights of the child as recognised under the CRC, those working with children and young people with SEND need to also recognise the legal entitlements which they further possess under both the Equality Act 2010 [

2] and the CFA 2014 [

3]. Whilst this project and the developed priorities aimed to be solution-focused and forward thinking, it is important to recognise that they are positioned within a SEND system which is acknowledged as underfunded and typically poorly equipped to meet the children with SEND’s needs. In order for these priorities to be realised and for children with SEND’s rights to be met, increased and sustained investment is needed from the Government across all sectors, as well as the proper implementation of the current SEND legal framework. The project also identified, as is well evidenced in existing literature, that there should be more integrated working across all services and between all professionals who work with and support children with SEND, as well as improved accountability and clearer lines of responsibility, to ensure equitable access to support across all regions of the UK.

4. Discussion

This paper outlines the process of conducting a multi-phase, multi-stakeholder mixed-methods study to collaboratively develop priorities for policy and practice from different perspectives, to ameliorate the enduring consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with SEND. By employing a rights-based approach, we identified five key priority areas highlighted by parents/carers, children and young people with SEND, and professionals: (1) My right to play, socialise, have fun, and be part of my community; (2) My right to support for my social and emotional wellbeing (SEW) and mental health; (3) My right to flexibility, choice, and support so I can feel safe, belong, and learn in school; (4) My right to health and social care services and therapies in order for me to stay healthy; and (5) My right to support for my parents/carers and my family. We endeavoured to create and develop these rights-based priorities with those most impacted, namely children with SEND and their parents/carers. In positioning these priorities against the duties which the UK Government have assumed pursuant to the CRC, which includes, amongst other rights, the right to rest, play and leisure (Article 31 CRC), the right to the highest attainable standard of health (Article 24 CRC), respect for the views of the child (Article 12 CRC), and the right to family support and an adequate standard of living (Article 27 CRC), the succeeding section engages with the wider children’s rights aspects which the priorities identified within this study relate to.

Another policy prioritisation study for child public health during COVID-19 [

37] described the ‘collateral damage’ (p. 533) to young people caused by the unintended consequences of COVID-19 restrictions in England. The priorities they identified were broadly similar to those identified here, including ensuring delivery of healthcare, mitigating the impact of disrupted schooling, supporting children’s deteriorating emotional wellbeing and mental health, and addressing child poverty and social inequalities. However, they noted how children and young people with SEND faced additional pressures during this period. What has become clear from the burgeoning literature on the impact of COVID-19 and associated restrictions on children and young people with SEND is the insufficient attention which the English Government accorded to their needs and rights [

13]. This in turn caused harm and exacerbated already prevalent inequalities for this vulnerable cohort [

18]. The legal measures enacted in the Coronavirus Act 2020 in England were affected within a rights-based vacuum and were bereft of a children’s rights or equality rights impact assessment. The consequences of these omissions were that the specific rights-based considerations were inconsistent with the guidance issued by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, the treaty-monitoring body of the CRC, who advocated for governments to consider, amongst other matters, the “health, social, educational, economic and recreational impacts of the pandemic on the rights of the child” [

38] (p. 1).

This assumes increased significance given that pre-pandemic SEND provision was already in a state of flux and decline. Research commissioned by the Department for Education and conducted by Adams et al. [

39] identified several key sources of parental dissatisfaction with the EHCP process. These included poor communication from local authorities, a lack of accessible information and support throughout the process, limited transparency around delays, insufficient involvement of families, inadequate detail within the EHCPs themselves, and a general failure to foster effective collaboration with schools and other agencies. Further highlighting systemic weaknesses, a 2019 Parliamentary report described the SEND framework as being plagued by confusion, unlawful practices, excessive bureaucracy, lack of accountability, insufficient resourcing, and an overly adversarial experience for families [

14]. Similarly, OFSTED [

40] reported that as of August 2019, 50 of the 100 Local Authority inspections completed (out of a total of 151) had resulted in a requirement to produce a Written Statement of Action due to significant weaknesses in their SEND arrangements. More broadly, research by Robinson et al. [

41] raised concerns that the implementation of the new legal and policy frameworks governing SEND provision coincided with a period of national and local austerity, leading to inconsistent and often “patchy provision” for children and young people. While acknowledging the positive intent behind such reforms, they cautioned that without robust oversight, such changes risked falling short of their goals, and recommended that the Government establish nationally consistent quality assurance and accountability mechanisms, underpinned by clear local structures and a well-trained specialist workforce, to ensure equitable and effective provision for all children with SEND, including those with EHCPs. Additionally, a 2018 survey conducted by the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) [

42] found that 94% of respondents reported increased difficulty in securing the necessary resources to support pupils with SEND compared to two years earlier. Notably, 73% attributed these challenges to broader financial cutbacks across the education sector.

Similarly, in their evaluation of the SEND framework two years post-implementation, Tysoe et al. [

43] found that SENDCos—key figures in the coordination and delivery of educational provision—were frequently unable to carry out their roles effectively. This was due to a combination of systemic issues, including increased administrative demands, poor communication from Local Authorities, insufficient external service provision, financial pressures, and delays in completing statutory needs assessments. These interconnected challenges significantly hindered the overall effectiveness of service delivery. Such conclusions corroborated earlier findings by Boesley and Crane [

44] who highlighted the concerns of SENDCos that the prevailing focus on academic attainment continued to shape perceptions of EHCPs primarily as educational tools, rather than as the integrated, wraparound support documents originally envisioned in the SEND reforms. Therefore, taken together, the pre-pandemic evidence on the reform and delivery of SEND services paints a fragmented and disjointed picture, revealing a system in which service provision was often inconsistent and difficult to navigate. Such shortcomings not only adversely affected children, their rights, and their long-term development and wellbeing, but also significantly undermined the core objectives of the Children and Families Act 2014.

Whilst the present study has confirmed the disproportionately negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people with SEND, what is now required is the robust articulation of the needs and priorities of children and young people with SEND as we enter the pandemic recovery phase. Central to these aims moving forward is the need for children’s rights law, as per the rights contained within the CRC, to be centrally considered within any future pandemic management. As Byrne and Lundy [

45] (p. 358) have previously reminded us in pre-pandemic times, “most public policies that affect children and young people, whether directly or indirectly, do not reference the CRC; indeed, many will have been designed by officials who have limited or no knowledge of its existence”. Such observations clearly materialised during COVID-19 when children’s rights law was inadequately given effect to, or complied with, during the legislative and policy responses to the pandemic. As Byrne and Lundy [

45] further argue, a child rights-based approach to policy making and delivery should involve the adoption of the CRC as the legal foundation upon which such policies are based on, and further that the process should directly involve children and young people, “and build their capacity as rights-holders to claim their rights” (p. 358). Indeed, Byrne and Lundy [

46] (p. 274), have elsewhere noted that the obligations arising under the CRC are “largely confined to the margins of policy-making”.

However, it is arguably within the context of a global pandemic that the rights and needs of the most vulnerable, and in particular children with SEND, should have been prioritised. The evidence from this research not only underlines the disproportionally adverse effects which COVID-19 had on children with SEND, but also exposes the pervasive rights-infringing impact which it exerted. From education, access to emotional and mental health support, to the ability to engage in play and recreation and maintain friendship groups, children and young people with SEND within this study have been clear on where future priorities must lie in the event of prospective lockdowns, pandemics, or restrictions. In this regard, it is contended that the rights contained within the CRC must become the legal bedrock of any future pandemic or lockdown management, with full consideration given by all policymakers to how the rights of children, and especially the most vulnerable, can be given full legal effect.

At the level of implementation, the primary responsibility for enforcing not only the specific priorities identified in this study, but the broader spectrum of children’s rights in the event of future lockdowns or public health restrictions, rests with central Government. This is principally due to its exclusive legislative authority to introduce and enforce such emergency measures. As this study contends, the protection and promotion of children’s rights must be foregrounded in any future legislative or policy response to emergent crises. This necessity is further underlined by findings from the global

CovidUnder19 initiative, which captured the perspectives of over 26,000 children across 137 countries concerning the recognition of their rights during the initial six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study reported that children widely perceived their voices as marginalised, concluding that “their governments were not considering children as a priority and were definitely not seeking their views when crucial policy responses to the pandemic were formulated and implemented” [

47] (p. 281). Significantly, the study emphasised that “at times of crisis, children’s rights … are not a dispensable luxury but an indispensable entitlement” [

47] (p. 282). These findings underscore the critical need for child rights respecting governance and the systematic incorporation of children’s rights into emergency response frameworks moving forward.

Children’s rights must become operationally centralised within all decision-making structures to avoid them becoming peripheral considerations or overlooked afterthoughts [

47]. This includes ensuring that fundamental children’s rights principles such as non-discrimination (Article 2 CRC), the best interests principle (Article 3 CRC), the right to life, survival and development of the child (Article 6 CRC), and the right of the child to participate in matter affecting them (Article 12 CRC), are properly assimilated into all decision-making structures at both macro and meso levels. Children’s rights law also necessitates that governments, in all their manifestations, including the responsibilities which fall on Local Authorities, “undertake all appropriate legislative, administrative, and other measures for the implementation of the rights recognised in the present Convention” (Article 4 CRC). This fundamental obligation cuts across the entire implementation of the CRC and has been interpreted broadly by the UN Committee [

48]. It requires, amongst other matters, reviewing of existing domestic legislation, visible cross-sectoral coordination between all levels of Government and between Government and civil society, the adoption of comprehensive and cohesive rights-based national strategies which are embedded in the convention, training and awareness raising, and the development and expansion of effective policies, programmes and services which establish real and achievable targets that transcend abstract statements of policy and practice. For children and young people with SEND, the above requirements impose clear and ongoing obligations on the state to ensure that the rights and needs of such children are upheld. In practical terms, and as we now enter the recovery phase of COVID-19, it means that central Government, in collaboration with Local Authorities, should partake in an ongoing review, to make sure that sufficient staffing, resources (technical, financial, informational etc.), and facilities are provided to ensure that the needs of children and young people with SEND are met. More widely, it also means that in the event of any future lockdowns or restrictions which impact children and young people with SEND, that the rights-based framework as contained within the CRC becomes the basis upon which decisions affecting children with SEND are instituted upon.

The suggestions outlined above assume increased importance in light of recent findings by the Children’s Commissioner for England [

49], who noted that children with SEND were not only more likely to feel less safe and lonelier than their non-SEND peers, but further, that their educational, health, and social care needs were disproportionately unfulfilled. This included long delays in the identification of their needs, the recognition that schools were often unable to meet their needs, the inaccessible nature of many children’s services including playgrounds, toilets, and wider leisure activities, poor quality care, discrimination, and the disruptive nature of the transition between important services for children and young people with SEND. Such findings, which corroborate many of the conclusions from the stakeholders within this paper, strengthen the call for a more cohesive, coordinated, and rights-based approach to the planning and provision of services for children with SEND.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has several limitations to consider. Firstly, the individuals who participated in this study were self-selecting and so may not be representative of the wider population. Indeed, the most isolated parents/carers and young people may not have had the time or technological resources to take part in a predominantly online study. Furthermore, while we made significant efforts to ensure that all children and young people who wanted to take part were able to do so, it is wholly possible that not all children’s needs were accounted for. In addition, participants in the final phase (workshops) were not anonymous to one another, which may have introduced social desirability bias. Further research should seek to conduct longitudinal research to assess whether and how identified priorities are taken up by the Government, and what outcomes they produce. Comparative research across national or regional contexts would also help elucidate context-specific barriers and enablers to inclusive policy implementation.