The Relationship Between Prematurity and Mode of Delivery with Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

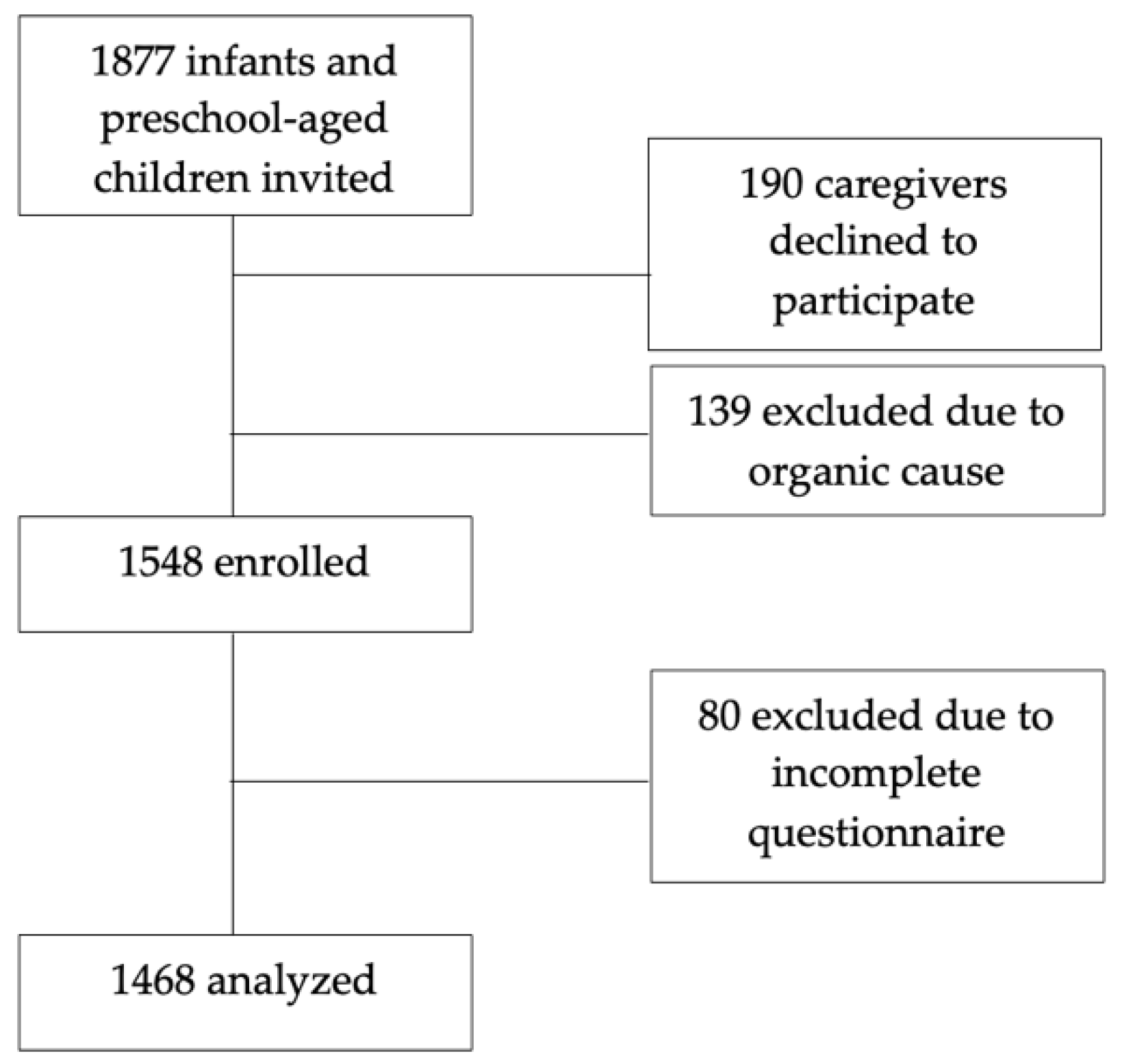

2.1. Participant Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGBI | Disorders of gut–brain interaction |

| FC | Functional constipation |

| IBS | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| QPGS-IV | Questionnaire of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rome IV |

References

- Hyams, J.S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Saps, M.; Shulman, R.J.; Staiano, A.; van Tilburg, M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palsson, O.S.; Tack, J.; Drossman, D.A.; Le Neve, B.; Quinquis, L.; Hassouna, R.; Ruddy, J.; Morris, C.B.; Sperber, A.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; et al. Worldwide population prevalence and impact of sub-diagnostic gastrointestinal symptoms. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, S.G.; Keller, C.; Zwiener, R.; Hyman, P.E.; Nurko, S.; Saps, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Shulman, R.J.; Hyams, J.S.; Palsson, O.; et al. Prevalence of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Utilizing the Rome IV Criteria. J. Pediatr. 2018, 195, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapar, N.; Benninga, M.A.; Crowell, M.D.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Mack, I.; Nurko, S.; Saps, M.; Shulman, R.J.; Szajewska, H.; van Tilburg, M.A.L.; et al. Paediatric functional abdominal pain disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, M.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S.; Rautava, S. Late preterm birth has direct and indirect effects on infant gut microbiota development during the first six months of life. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olen, O.; Stephansson, O.; Backman, A.S.; Tornblom, H.; Simren, M.; Altman, M. Pre- and perinatal stress and irritable bowel syndrome in young adults-A nationwide register-based cohort study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30, e13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Benitez, C.A.; Axelrod, C.H.; Gutierrez, S.; Saps, M. The Relationship Between Prematurity, Method of Delivery, and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, e37–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waehrens, R.; Li, X.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K.; Zoller, B. Perinatal and familial risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome in a Swedish national cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjolund, J.; Uusijarvi, A.; Tornkvist, N.T.; Kull, I.; Bergstrom, A.; Alm, J.; Tornblom, H.; Olen, O.; Simren, M. Prevalence and Progression of Recurrent Abdominal Pain, From Early Childhood to Adolescence. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 930–938.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautava, S.; Luoto, R.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Microbial contact during pregnancy, intestinal colonization and human disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escherich, T. The intestinal bacteria of the neonate and breast-fed infant. 1884. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1988, 10, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aagaard, K.; Ma, J.; Antony, K.M.; Ganu, R.; Petrosino, J.; Versalovic, J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 237ra265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, M.C.; Rautava, S.; Aakko, J.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanh, B.Y.L.; Lumbiganon, P.; Pattanittum, P.; Laopaiboon, M.; Vogel, J.P.; Oladapo, O.T.; Pileggi-Castro, C.; Mori, R.; Jayaratne, K.; Qureshi, Z.; et al. Mode of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in preterm birth: A secondary analysis of the WHO Global and Multi-country Surveys. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Williams, D.; Lemas, D.J.; Spiryda, L.; Patel, K.; Carney, O.O.; Neu, J.; Carson, T.L. The Neonatal Microbiome and Its Partial Role in Mediating the Association between Birth by Cesarean Section and Adverse Pediatric Outcomes. Neonatology 2018, 114, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.N.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Shen, X.Z.; Liu, T.T. Altered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.Q.; Huang, M.J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, N.N.; Tao, S.; Zhang, M. Early life adverse exposures in irritable bowel syndrome: New insights and opportunities. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1241801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abomoelak, B.; Saps, M.; Sudakaran, S.; Deb, C.; Mehta, D. Gut Microbiome Remains Static in Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders Patients Compared to Controls: Potential for Diagnostic Tools. BioTech 2022, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abomoelak, B.; Pemberton, V.; Deb, C.; Campion, S.; Vinson, M.; Mauck, J.; Manipadam, J.; Sudakaran, S.; Patel, S.; Saps, M.; et al. The Gut Microbiome Alterations in Pediatric Patients with Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Benitez, C.A.; Gomez-Oliveros, L.F.; Rubio-Molina, L.M.; Tovar-Cuevas, J.R.; Saps, M. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Rome IV Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondim, M.; Goulart, A.L.; Morais, M.B. Prematurity and functional gastrointestinal disorders in infancy: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, J.K.; Lenhart, A.; Yang, P.L.; Heitkemper, M.M.; Baker, J.; Keefer, L.; Saps, M.; Cuff, C.; Hungria, G.; Videlock, E.J.; et al. Risk Factors for Abdominal Pain-Related Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction in Adults and Children: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 995–1023.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreau, F.; Ferrier, L.; Fioramonti, J.; Bueno, L. New insights in the etiology and pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome: Contribution of neonatal stress models. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 62, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannampalli, P.; Pochiraju, S.; Chichlowski, M.; Berg, B.M.; Rudolph, C.; Bruckert, M.; Miranda, A.; Sengupta, J.N. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) and prebiotic prevent neonatal inflammation-induced visceral hypersensitivity in adult rats. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 1694–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staller, K.; Olen, O.; Soderling, J.; Roelstraete, B.; Tornblom, H.; Kuo, B.; Nguyen, L.H.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Antibiotic use as a risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome: Results from a nationwide, case-control study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Hern Tan, L.T.; Ramadas, A.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Lee, L.H. Exploring the Role of Gut Bacteria in Health and Disease in Preterm Neonates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Zablah, R.A.; Vazquez-Frias, R. Unraveling the complexity of Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction: The gut microbiota connection in children. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1283389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Luo, X.; Zhou, L.; Xie, R.H.; He, Y. Microbiota transplantation in restoring cesarean-related infant dysbiosis: A new frontier. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2351503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Palumbo, I.; Trilli, I.; Guglielmo, M.; Mancini, A.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Dipalma, G. The Impact of Cesarean Section Delivery on Intestinal Microbiota: Mechanisms, Consequences, and Perspectives-A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.M.; Benninga, M.A.; Di Lorenzo, C. Epidemiology of childhood constipation: A systematic review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 2401–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, R.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Remes-Troche, J.; Robin, D.; Shun, E.; Aravind, T. Exploring cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) worldwide: Current epidemiological insights and recent developments. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 37, e14932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | ||

| X ± SD | 24.2 ± 15 | |

| Range | 1–53 | |

| Age groups | ||

| 1–12 months | 515 | 35.1 |

| 1–4 years | 953 | 64.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 724 | 49.3 |

| Male | 744 | 50.7 |

| Race | ||

| White | 528 | 36 |

| Mixed ethnic background | 525 | 35.8 |

| Indigenous | 339 | 23.1 |

| Black | 76 | 5.2 |

| City | ||

| Florencia | 702 | 47.8 |

| Sotavento | 310 | 21.1 |

| Cali | 301 | 20.5 |

| Bogota | 155 | 10.6 |

| Children with DGBI (n = 390) | All Children (n = 1468) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional constipation | 328 | 84.1% | 22.3% |

| Infant colic * (n = 126) | 5 | 1.3% | 4% |

| Infant regurgitation ** (n = 515) | 16 | 4.1% | 3.1% |

| Cyclic vomiting syndrome | 32 | 8.2% | 2.2% |

| Infant dyschezia *** (n = 253) | 3 | 0.8% | 1.2% |

| Rumination syndrome | 3 | 0.8% | 0.2% |

| Functional diarrhea | 3 | 0.8% | 0.2% |

| Infants 1–12 Months n = 515 (%) | Children 1–4 Years n = 953 (%) | Total n = 1468 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| X +/− SD | 8.3 +/− 3.9 | 2.7 +/− 0.9 | |

| Functional constipation | 56 (10.9%) | 272 (28.5%) | 328 (22.3%) |

| Infant colic | 5 (4%) | N/A | 5 (0.3%) |

| Infant regurgitation | 16 (3.1%) | N/A | 16 (1%) |

| Cyclic vomiting syndrome | 0 | 32 (3.4%) | 32 (2.2%) |

| Infant dyschezia | 3 (1.2%) | N/A | 3 (0.2%) |

| Rumination syndrome | 0 | 3 (0.3%) | 3 (0.2%) |

| Functional diarrhea | 0 | 3 (0.3%) | 3 (0.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco-Benitez, C.A.; Velasco-Suarez, D.A.; Palma, N.; Arrizabalo, S.; Saps, M. The Relationship Between Prematurity and Mode of Delivery with Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Children. Children 2025, 12, 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060799

Velasco-Benitez CA, Velasco-Suarez DA, Palma N, Arrizabalo S, Saps M. The Relationship Between Prematurity and Mode of Delivery with Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Children. Children. 2025; 12(6):799. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060799

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco-Benitez, Carlos Alberto, Daniela Alejandra Velasco-Suarez, Natalia Palma, Samantha Arrizabalo, and Miguel Saps. 2025. "The Relationship Between Prematurity and Mode of Delivery with Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Children" Children 12, no. 6: 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060799

APA StyleVelasco-Benitez, C. A., Velasco-Suarez, D. A., Palma, N., Arrizabalo, S., & Saps, M. (2025). The Relationship Between Prematurity and Mode of Delivery with Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction in Children. Children, 12(6), 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060799