Pediatric Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa of the Cervical Esophagus (Inlet Patch): Case Series with Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Correlation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

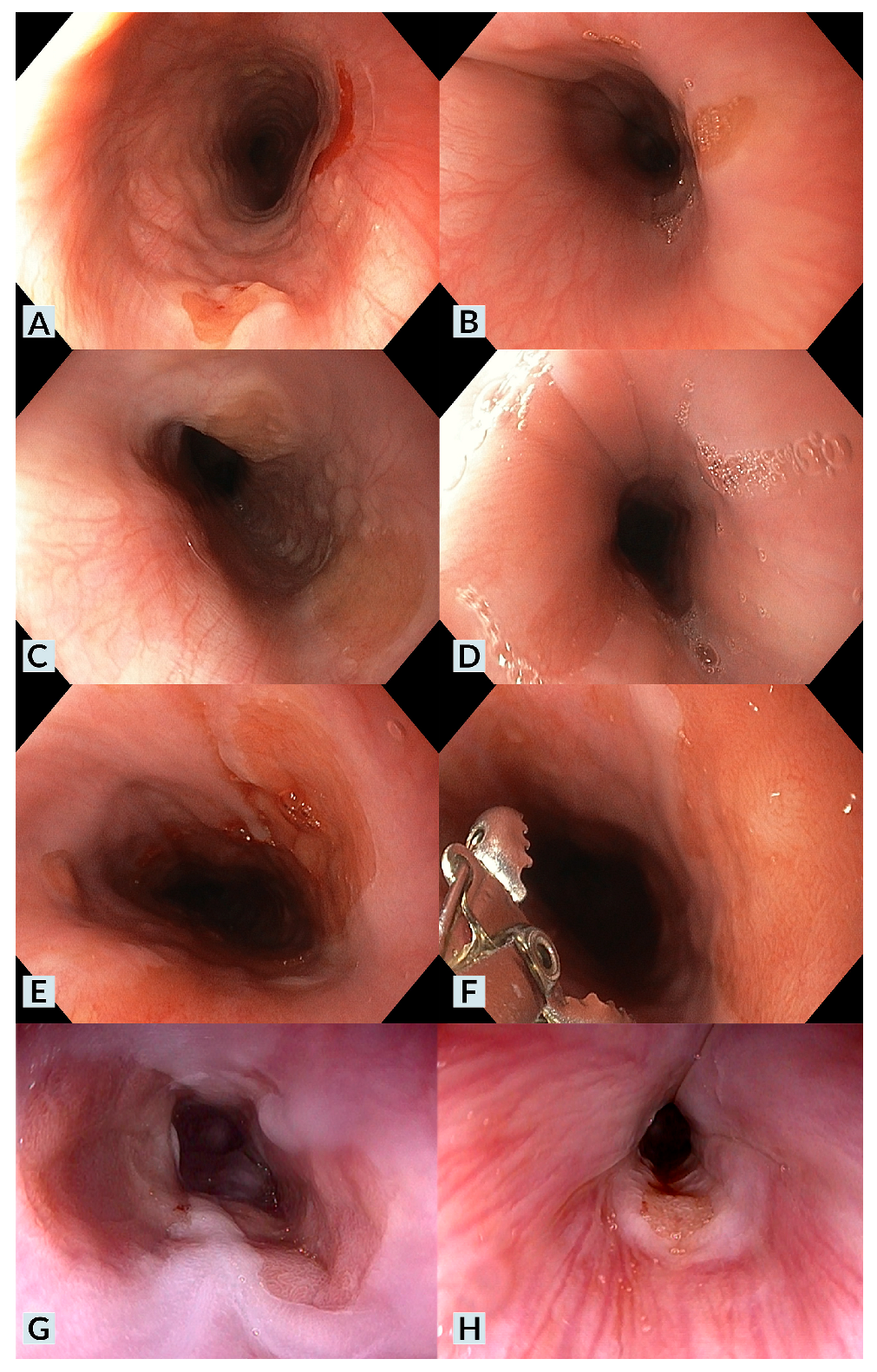

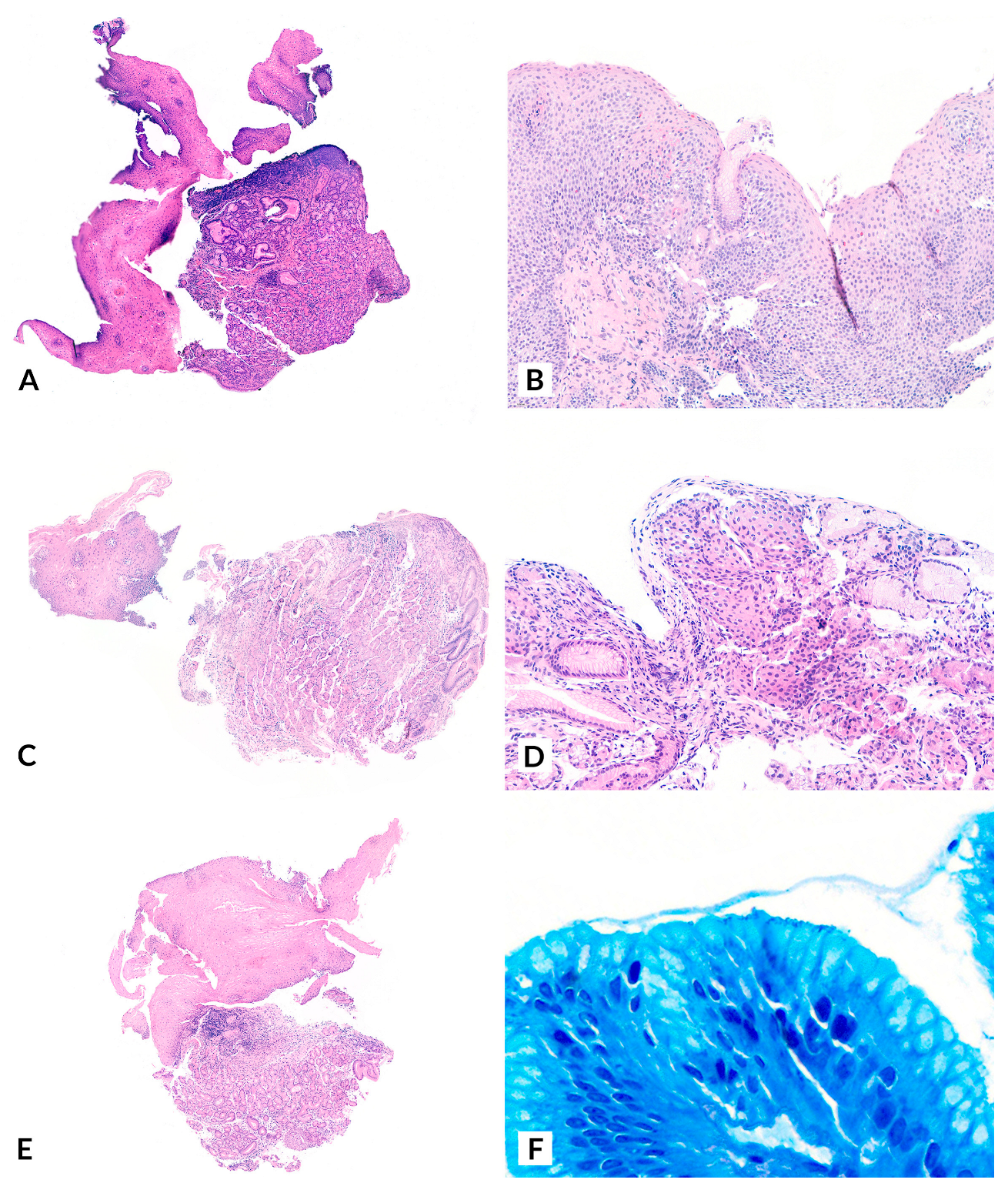

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; Salazar-Quero, J.C.; Tutau-Gómez, C.; Espín-Jaime, B.; Rubio-Murillo, M.; Pizarro-Martín, A. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the proximal oesophagus (inlet patch): Endoscopic prevalence, histological and clinical characteristics in paediatric patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 26, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, A.; Coopman, S.; Rebeuh, J.; Molitor, G.; Rebouissoux, L.; Dabadie, A.; Kalach, N.; Lachaux, A.; Michaud, L. Inlet patch: Clinical presentation and outcome in children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nardo, G.; Cremon, C.; Bertelli, L.; Oliva, S.; De Giorgio, R.; Pagano, N. Esophageal Inlet Patch: An Under-Recognized Cause of Symptoms in Children. J. Pediatr. 2016, 176, 99–104.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borhan-Manesh, F.; Farnum, J.B. Incidence of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus. Gut 1991, 32, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akar, T.; Aydın, S. The true prevalence of cervical inlet patch in a specific center dealing with esophageal diseases. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3127–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Variend, S.; Howat, A.J. Upper oesophageal gastric heterotopia: A prospective necropsy study in children. J. Clin. Pathol. 1988, 41, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yin, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, J.; Zheng, K.; Yoshida, E.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Shao, X.; Qi, X. Prevalence and Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics of Cervical Inlet Patch (Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, e250–e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogomoletz, W.V.; Geboes, K.; Feydy, P.; Nasca, S.; Ectors, N.; Rigaud, C. Mucin histochemistry of heterotopic gastric mucosa of the upper esophagus in adults: Possible pathogenic implications. Hum. Pathol. 1988, 19, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwers, G.Y.; Mino, M.; Ban, S.; Forcione, D.; Eatherton, D.E.; Shimizu, M.; Sevestre, H. Cytokeratins 7 and 20 and mucin core protein expression in esophageal cervical inlet patch. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005, 29, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meliț, L.E.; Dincă, A.L.; Borka Balas, R.; Mocanu, S.; Mărginean, C.O. Not Every Dyspepsia Is Related to Helicobacter pylori-A Case of Esophageal Inlet Patch in a Female Teenager. Children 2023, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trippel, M.; Casaulta, C.; Sokollik, C. Heterotopic gastric mucosa: Esophageal inlet patch in a child with chronic bronchitis. Dig. Endosc. 2016, 28, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-García, A.; Sáez Álvarez, S.; González-Lamuño Sanchis, C.; Iglesias Blázquez, C.; Rodríguez Ruiz, M.; Arredondo Montero, J. Esophageal inlet patch in a 7-year-old girl with subacute dysphagia. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2024, 65, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macha, S.; Reddy, S.; Rabah, R.; Thomas, R.; Tolia, V. Inlet patch: Heterotopic gastric mucosa—Another contributor to supraesophageal symptoms? J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, K.; Shibagaki, K.; Nonomura, S.; Sumi, S.; Fukuda, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Kotani, S.; Okimoto, E.; Oshima, N.; Kawashima, K.; et al. Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa in Middle Esophagus Complicated with Esophageal Ulcers. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 2735–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alberty, J.B.; Chanis, R.; Khoshoo, V. Symptomatic gastric inlet patches in children treated with argon plasma coagulation: A case series. J. Interv. Gastroenterol. 2012, 2, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peitz, U.; Vieth, M.; Evert, M.; Arand, J.; Roessner, A.; Malfertheiner, P. The prevalence of gastric heterotopia of the proximal esophagus is underestimated, but preneoplasia is rare–correlation with Barrett’s esophagus. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ajmal, S.; Young, J.S.; Ng, T. Adenocarcinoma arising from cervical esophageal gastric inlet patch. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 1664–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, A.; Schaller, T.; Messmann, H. Adenocarcinoma arising from ectopic gastric mucosa in an esophageal inlet patch: Treatment by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy 2015, 47 (Suppl. S1), UCTN:E337-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrie, A. Adenocarcinoma of the upper end of the esophagus arising from ectopic gastric epithelium. Br. J. Surg. 1950, 37, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, W.N.; Sternberg, S.S. Adenocarcinoma of the upper esophagus arising in ectopic gastric mucosa: Two case reports and review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1987, 11, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C. A case of adenocarcinoma of the upper third of the esophagus arising on ectopic gastric tissue. Tumori 1974, 60, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, G.; Nakamura, K.; Saito, K.; Shuto, K.; Shiratori, T.; Kono, T.; Uesato, M.; Sato, A.; Isozaki, Y.; Maruyama, T.; et al. Primary adenocarcinoma of the esophagus arising from heterotopic gastric glands. Gan No Rinsho 1970, 16, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.; Riddell, R.H.; Walther, B.; Skinner, D.B.; Riemann, J.F.; Groitl, H. Adenocarcinoma of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the proximal esophagus. Leber Magen Darm 1985, 15, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Ushiku, T.; Ikemura, M.; Shibahara, J.; Seto, Y.; Fukayama, M. Esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in cervical inlet patch with synchronous Barrett’s esophagus-related dysplasia. Pathol. Int. 2014, 64, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, R.; Patel, J.; Song, J.; Malik, Z.; Smith, M.S.; Parkman, H.P. Esophageal Inlet Patch: Association with Barrett’s Esophagus. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 3671–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbari, M.; Goresky, C.A.; Lough, J.; Yaffe, C.; Daly, D.; Côté, C. The inlet patch: Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus. Gastroenterology 1985, 89, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.A.; Kang, D.H.; Cho, H.S.; Park, D.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, H.C.; Kim, J.H. Acid secretion from a heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus demonstrated by dual probe 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutierrez, O.; Akamatsu, T.; Cardona, H.; Graham, D.Y.; El-Zimaity, H.M. Helicobacter pylori and hetertopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus (the inlet patch). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 98, 1266–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagozlu, H.; Simsek, Z.; Unal, S.; Cindoruk, M.; Dumlu, S.; Dursun, A. Is there an association between Helicobacter pylori in the inlet patch and globus sensation? World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Patient | Age | Sex | Medical History | Cervical Esophageal Symptoms | IP Diagnosis | UGIE Findings | H. pylori | Pathology | Treatment | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7y | Female | - | Dysphagia *** | Urgent UGIE for dysphagia | IP (multiple lesions, villous/nodular pattern) | No | IP with mild chronic inflammation | PPI | Favorable |

| 2 | 12y | Male | Prematurity, EoE | Food impaction. Dysphagia | Incidental finding (EoE control) | EoE EREFS 2 (Edema 1, Furrows 1). IP (multiple lesions) | No | IP with mild chronic inflammation. EoE | PPI | Favorable |

| 3 | 6y | Male | Adenoid and tonsil hypertrophy, adenoidectomy, and tonsillectomy | None | Incidental finding (Urgent, tonsillar bleeding) | Tonsillar postsurgical bleeding. IP (villous/nodular pattern) | No | IP with mild chronic inflammation | - | Favorable |

| 4 | 14y | Female | Celiac disease | None | Incidental finding (Celiac disease control) | EoE endoscopic findings. Cobblestone gastric pattern. IP | Yes | Duodenum without villous atrophy but with a slight increase in lymphocytes. Moderate-to-severe chronic gastritis (H. pylori+). IP with moderate-to-severe chronic inflammation. EoE | Gluten-free diet. PPI. H. pylori treatment * | Favorable |

| 5 | 11y | Male | Epigastric pain secondary to H. pylori gastritis * | None | Incidental finding (abdominal pain) | Petechial antral gastritis. IP | Yes | Chronic duodenitis. Moderate-to-severe chronic gastritis. (H. pylori+). IP with moderate-to-severe chronic inflammation | PPI H. pylori treatment * | Favorable |

| 6 | 10y | Male | - | GER-related symptoms. Dysphagia | Elective UGIE for dysphagia | Nodular antritis. IP (multiple lesions, villous/nodular pattern) | Yes | Moderate-to-severe chronic gastritis. (H. pylori+). IP with moderate-to-severe chronic inflammation. (H. pylori + in IP, Giemsa stain) | PPI H. pylori treatment ** | Favorable |

| 7 | 13y | Male | EoE | Food impaction. Dysphagia | Incidental finding (EoE control) | EoE endoscopic findings. IP | No | IP with mild chronic inflammation. EoE | PPI. Topical corticosteroids | Favorable |

| 8 | 13y | Male | Insulin-dependent type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.Lactose intolerance | GER-related symptoms *** | Incidental finding (abdominal pain) | IP | No | IP with mild chronic inflammation | Dietary modification. PPI | Favorable |

| 9 | 13y | Male | EoE. Positive serology and compatible genetics (DQ2/DQ8) for celiac disease | GER-related symptoms. Dysphagia *** | Elective UGIE for dysphagia | Duodenal biopsy MARSH 1. EoE endoscopic findings. IP. | No | IP with moderate-to-severe chronic inflammation. | Gluten-free and cow’s milk protein-free diet. PPI + cinitapride. | Favorable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arredondo Montero, J.; Sáez Álvarez, S.; Herreras Martínez, A.; Fernández-García, A.; Iglesias Blázquez, C. Pediatric Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa of the Cervical Esophagus (Inlet Patch): Case Series with Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Correlation. Children 2025, 12, 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060752

Arredondo Montero J, Sáez Álvarez S, Herreras Martínez A, Fernández-García A, Iglesias Blázquez C. Pediatric Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa of the Cervical Esophagus (Inlet Patch): Case Series with Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Correlation. Children. 2025; 12(6):752. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060752

Chicago/Turabian StyleArredondo Montero, Javier, Samuel Sáez Álvarez, Andrea Herreras Martínez, Ana Fernández-García, and Cristina Iglesias Blázquez. 2025. "Pediatric Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa of the Cervical Esophagus (Inlet Patch): Case Series with Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Correlation" Children 12, no. 6: 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060752

APA StyleArredondo Montero, J., Sáez Álvarez, S., Herreras Martínez, A., Fernández-García, A., & Iglesias Blázquez, C. (2025). Pediatric Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa of the Cervical Esophagus (Inlet Patch): Case Series with Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histopathological Correlation. Children, 12(6), 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060752