Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults After Testicular Prosthesis Surgery During Childhood: A Qualitative Study and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

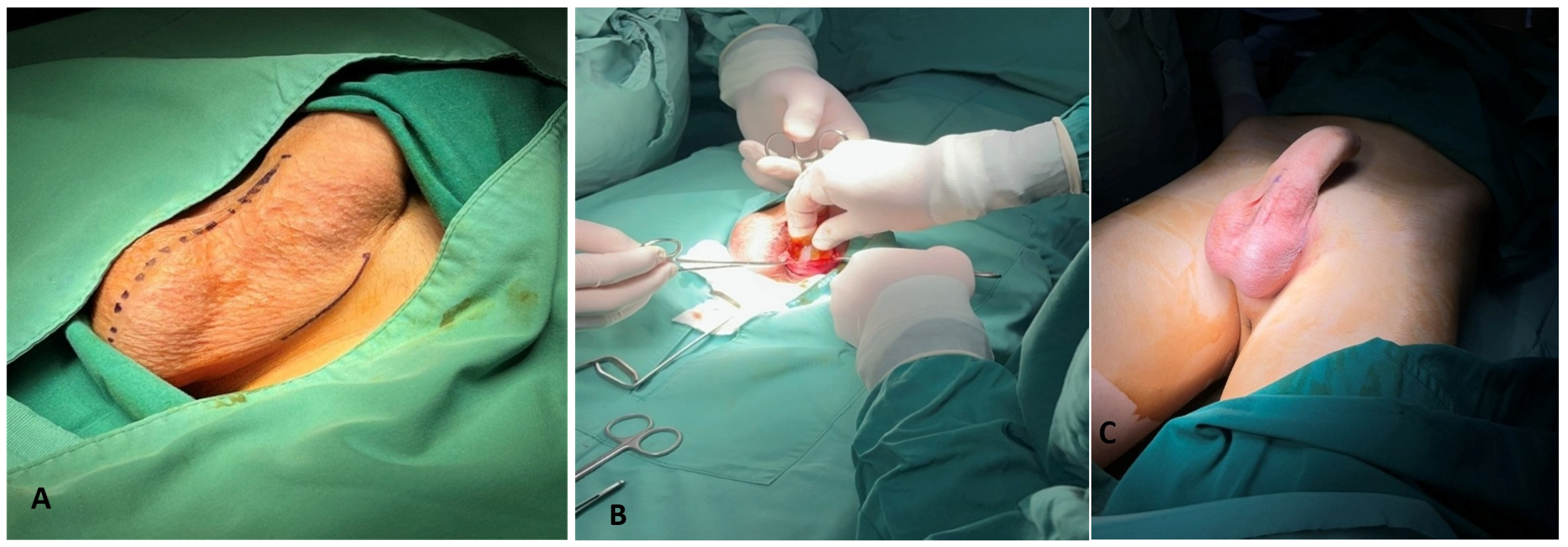

2.2. The Operation and the Prosthesis Material

2.3. The Interview

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Outcomes of the Study

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. Quality of Life Domain Outcomes

3.2.1. Physical Health

- Feeling of the testicular prosthesis

- Restriction of activities

- Perceptions on fertility

3.2.2. Mental Health

- Self-image

- Self-respect

- Feelings

3.2.3. Interpersonal Relationships

- Same-age peers

- Intimate partner

3.2.4. Family Communication

- Communicating with family members

- Communicating consent for surgery with the family

3.2.5. Access to Information

3.2.6. Sexual Life

- Perception on the effect of the testicular prosthesis on sexual life

- Quality of sexual activity

3.3. What About Those Who Denied Participation in the Study?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matthew-Onabanjo, A.N.; Honig, S. Testicular prosthesis: A historical and current review of the literature. Sex. Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelic, Z.; Neumann, C.; Jukic, M. An unusual presentation of testicular torsion in children: A single-centre retrospective study. Can. J. Urol. 2019, 26, 10026–10032. [Google Scholar]

- Turek, P.J.; Master, V.A.; Testicular Prosthesis Study Group. Safety and effectiveness of a new saline filled testicular prosthesis. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivatsav, A.; Balasubramanian, A.; Butaney, M.; Thirumavalavan, N.; McBride, J.A.; Gondokusumo, J.; Pastuszak, A.W.; Lipshultz, L. Patient attitudes toward testicular prosthesis placement after orchiectomy. Am. J. Men’s Health. 2019, 13, 1557988319861019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, S. The clinical utility of testicular prosthesis placement in children with genital and testicular disorders. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2014, 3, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Arajuo, A.S.; Anacleto, S.; Rodrigues, R.; Tinoco, C.; Cardoso, A.; Oliveira, C.; Leao, R. Testicular prosthesis-impact on quality of life and sexual function. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 26, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberman, D.; Winkler, H.; Kleinmann, N.; Raviv, G.; Chertin, B.; Ramon, J.; Mor, Y. Testicular prosthesis insertion following testicular loss or atrophy during early childhood-technical aspects and evaluation of patient satisfaction. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2007, 3, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhanakrishnan, R.; Konamme, V.K.; Saroja, M.G. Concurrent placement of the testicular prosthesis in children following orchiectomy/testicular loss. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 28, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemlak, P.; Jedrzejewski, G.; Cielecki, C.; Kalinska-Lipert, A.; Wieczorek, A.; Nachulewicz, P. The use of testicular prosthesis in boys. Medicine 2018, 97, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peycelon, M.; Rossignol, G.; Muller, C.O.; Carricaburu, E.; Philippe-Chomette, P.; Paye-Jaouen, A.; El Ghoneimi, A. Testicular prosthesis in children: Is earlier better? J. Pediatr. Urol. 2016, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, L.; Tagliagambe, S. Quantitative medicine: Tracing the transition from holistic to reductionist approaches. A new “quantitative holism” is possible? J. Pub. Health Res. 2023, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heale, R.; Twycross, A. Validity and reliability in quantitative studies. Evid. Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.M.; Little, M. Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzoukas, S. Issues of representation within qualitative inquiry. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.; Bijayni, J.; Kalra, S. Qualitative research. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2013, 4, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, H.; Chan, K. Quality over quantity: How qualitative research informs and improves quantitative research. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 655–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, K.; Neuzil, K.; Basak, R.; Chan, K. Quality of reporting for qualitative studies in pediatric urology-a scoping review. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzil, K.; McCloskey, K.; Chan, K. Qualitative research in pediatric urology. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, A.; Bates, E.A. “I want my mum to know that I am a good guy…”: A thematic analysis of the accounts of adolescents who exhibit child-to-parent violence in the United Kingdom. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP6135–NP6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakola, M. Child-centered qualitative interview (Chapter 5). In Methods in Practice: Studying Children and Youth Online; Kotilainen, S., Ed.; CO:RE Children Online: Research and Evidence: Hamburg, Germany, 2022; pp. 20–23. Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/83031 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Greswell, J.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M.; Leeman, J. Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.A. Testicular nubbins and prosthesis insertion: Is it all just in the timing? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2007, 23, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xylinas, E.; Martinache, G.; Azancot, V.; Amsellem-Ouzana, D.; Saighi, D.; Flam, T.; Zerbib, M.; Debre, B.; Peyromaure, M.; Descazeaud, A. Testicular implants, patient’s and partner’s satisfaction: A questionnaire-based study of men after orchidectomy. Prog. Urol. 2008, 18, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adshead, J.; Khoubehi, B.; Wood, J.; Rustin, G. Testicular implants and patient satisfaction: A questionnaire-based study of men after orchidectomy for testicular cancer. BJY Int. 2001, 88, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodiwala, D.; Summerton, D.J.; Terry, T.R. Testicular prostheses: Development and modern usage. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2007, 89, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, K.P.; Anheuser, P.; Schmidt, S.; Soyka-Hundt, B.; Pichlmeier, U.; Schriefer, P.; Matthies, C.; Hartmann, M.; Ruf, C.G. Testicular prostheses in patients with testicular cancer-acceptance rate and patient satisfaction. BMC Urol. 2015, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, N.; Saniye, E.; Ibrahim, K.; Cliftci, A.O.; Cahit, T.F.; Emin, S.M. Testicular prosthesis implantation in children. Acta Med. 2017, 48, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, T.G.; Burg, M.L.; Hu, B.; Loh-Doyle, J.; Hugen, C.M.; Cai, J.; Djaladat, H.; Wayne, K.; Daneshmand, S. Satisfaction with testicular prosthesis after radical orchiectomy. Urology 2018, 114, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayon, S.; Michel, J.; Coward, R.M. The modern testicular prosthesis: Patient selection and counseling, surgical technique, and outcomes. Asian J. Androl. 2020, 22, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossepowitch, O.; Aviv, D.; Wainchwaig, L.; Baniel, J. Testicular prostheses for testis cancer survivors: Patient perspectives and predictors of long-term satisfaction. J. Urol. 2011, 18, 2249–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.; Yassin, M.; Walker, H.D. Contemporary practice of testicular prosthesis insertion. Arab J. Urol. 2015, 13, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.X.; Yang, S.; Ning, Y.; Shao, H.H.; Ma, M.; Tian, R.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Gao, W.Q.; Li, Z.; Xia, W.L. Novel double-layer silastic testicular prosthesis with controlled release of testosterone in in vitro, and its effects on castrated rats. Asian J. Androl. 2017, 19, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nichols, P.E.; Harris, K.T.; Brant, A.; Manka, M.G.; Haney, N.; Johnson, M.H.; Herati, A.; Allaf, M.E.; Pierorazio, P.M. Patient decision-making and predictors of genital satisfaction associated with testicular prostheses after radical orchiectomy: A questionnaire-based study of men with germ cell tumors of the testicle. Urology 2019, 124, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzariti, F.; Polito, B.; Polito, M. Testicular prosthesis: Patient satisfaction and sexual dysfunction in testis cancer survivors. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2016, 88, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Y.; Millan, A.; Gilabert, R.; Delgado, L.; De Agustin, J.C. Study on satisfaction of testicular prosthesis implantation in children. Cir. Pediatr. 2012, 25, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hampl, D.; Koifman, L.; Celino, E.F.; Araujo, L.R.; Sampaio, F.J.; Favorito, L.A. Is there bacterial growth inside the tunica vaginalis cavity in patients with unsalvageable testicular torsion? Urology 2021, 149, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.J.; Pryor, J.P. Testicular prostheses: The patient’s perception. Br. J. Urol. 1992, 70, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incrocci, L.; Bosch, J.L.; Slob, A.K. Testicular prostheses: Body image and sexual functioning. BMJ Int. 1999, 84, 1043–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta Zaragozano, J.; Fons Estupina, C.; Lopez Lopez, J.A.; Valvidia Uria, J.G. Implante de protesis testicularis en la infancia y dolescencia. An. Pediatr. 2005, 62, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.S., Jr.; Williams, H.; Agarwal, S.K.; De Bolla, A.R. Unilateral spontaneous rupture of a testicular implant thirteen years after bilateral insertion: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2010, 4, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Questions Addressed to the Recipient |

|---|

| Are there any types of pain or discomfort impeding you from certain activities after the testicular prosthesis implantation? |

| Is there anything you believe that you are not able to do because of the testicular prosthesis? |

| Do you feel that you are affected by the comments of others, i.e., friends, classmates, in regard to your body image? |

| Did the testicular prosthesis modify your feelings and thoughts about yourself and your abilities? |

| How satisfied are you by yourself after the implantation of the testicular prosthesis? |

| Did you wish to discuss and share with your family, companion, friends, your feelings and thoughts, or certain practical issues on the testicular prosthesis implantation? |

| Could you describe the thoughts you had on your future sexual life before surgery? |

| Do you feel that the testicular prosthesis has affected your sexual life? |

| Do you consider that you have obtained from your doctor all the information you needed on the testicular prosthesis implantation? |

| Was the information you needed regarding the testicular prosthesis made available to you fully? |

| How does it feel to have the testicular prosthesis? |

| Did your doctor or your parents explain to you the reason for the testicular prosthesis? |

| What would you advise a young person to do, if he was in the same condition with you? |

| If you lost your testicular prosthesis, would you decide to have it implanted again? |

| Questions addressed to the recipient’s parents |

| Does he report any body complains or discomfort after the implantation of the testicular prosthesis? |

| Did he express before or after surgery any thoughts that his health might be compromised by the prosthesis? |

| Did he express his feelings, either positive or negative, regarding the testicular prosthesis? |

| Do you remember if he is affected by the comments of friends, classmates, or others in regard to his body image? |

| Is he able to communicate and share information, feelings and thoughts about himself after the testicular prosthesis implantation? |

| Has he expressed thoughts or concerns on his sexual life or intimate relationships? |

| Does he feel any restrictions in his life? |

| Did you discuss his problem with him, and did you ask him about the operation? |

| Do you believe that the doctor informed you in detail and answered all you questions on his health problem and the implantation of the testicular prosthesis? |

| Did you ever doubt his fertility and sexual life? |

| Are you afraid of something about his future? |

| Would you communicate and share with the family or others your own feelings and thoughts regarding his testicular prosthesis? |

| What would you advise a family in your own position today? |

| Recipient Code | Age at Surgery (Years) | Age at Interview (Years) | Time from Surgery (Years) | Primary Testicular Disease | Occupation | Personal Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R01 | 16 | 17 | 1 | Testicular atrophy | Student | In relationship |

| R02 | 13 | 15 | 2 | Testicular torsion | Student | Single |

| R03 | 13 | 17 | 4 | Undescended testis | Student | Occasional relationships |

| R04 | 9 | 11 | 2 | Undescended testis | Student | Single |

| R05 | 14 | 16 | 2 | Testicular torsion | Student | Single |

| R06 | 14 | 23 | 9 | Antenatal testicular torsion | University student | In relationship |

| R07 | 13 | 23 | 10 | Testicular atrophy | University student | In relationship |

| R08 | 9 | 22 | 13 | Testicular atrophy | Self-employed | Occasional relationships |

| R09 | 14 | 27 | 13 | Undescended testis | University student | Occasional relationships |

| R10 | 14 | 22 | 8 | Undescended testis | University student | Occasional relationships |

| R11 | 12 | 25 | 13 | Undescended testis | University student | Occasional relationships |

| R12 | 8 | 14 | 6 | Undescended testis | Student | Single |

| R13 | 14 | 21 | 7 | Neonatal testicular torsion | University student | In relationship |

| R14 | 15 | 22 | 7 | Anorchidism | University student | Single |

| R15 | 12 | 13 | 1 | Testicular torsion | Student | Single |

| R16 | 14 | 18 | 4 | Bilateral atrophic hypogonadism | University student | Single |

| Parental Code | Age in Years | Family Status | Education Level | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR01 | 47 | Single | High school | Private employee |

| FR01 | 46 | Divorced | High school | Private employee |

| MR02 | 44 | Married | University | Self-employed |

| FR02 | 49 | Married | University | Self-employed |

| FR03 | 51 | Married | High school | Public employee |

| MR04 | 50 | Married | High school | Private employee |

| FR04 | 49 | Married | High school | Private employee |

| MR05 | 44 | Married | High school | Housekeeper |

| FR05 | 54 | Married | High school | Self employed |

| MR12 | 46 | Widow | High school | Unemployed |

| MR15 | 48 | Married | University | Public employee |

| FR15 | 50 | Married | University | Self-employed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chantzi, Z.; Fouzas, S.; Drivalos, A.; Stamati, A.; Gkentzis, A.; Athanasopoulou, M.; Kambouri, K.; Gkentzi, D.; Kostopoulou, E.; Vareli, A.; et al. Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults After Testicular Prosthesis Surgery During Childhood: A Qualitative Study and Literature Review. Children 2025, 12, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060720

Chantzi Z, Fouzas S, Drivalos A, Stamati A, Gkentzis A, Athanasopoulou M, Kambouri K, Gkentzi D, Kostopoulou E, Vareli A, et al. Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults After Testicular Prosthesis Surgery During Childhood: A Qualitative Study and Literature Review. Children. 2025; 12(6):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060720

Chicago/Turabian StyleChantzi, Zoi, Sotirios Fouzas, Alexandros Drivalos, Athanasia Stamati, Agapios Gkentzis, Maria Athanasopoulou, Katerina Kambouri, Despoina Gkentzi, Eirini Kostopoulou, Anastasia Vareli, and et al. 2025. "Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults After Testicular Prosthesis Surgery During Childhood: A Qualitative Study and Literature Review" Children 12, no. 6: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060720

APA StyleChantzi, Z., Fouzas, S., Drivalos, A., Stamati, A., Gkentzis, A., Athanasopoulou, M., Kambouri, K., Gkentzi, D., Kostopoulou, E., Vareli, A., Blevrakis, E., Zachos, K., Alexopoulos, V., Panagidis, A., Plotas, P., Louta, A., Karatza, A. A., Dassios, T., Dimitriou, G., ... Sinopidis, X. (2025). Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults After Testicular Prosthesis Surgery During Childhood: A Qualitative Study and Literature Review. Children, 12(6), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060720