Patient Empowerment Among Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Use of Counseling Services and Lack of Knowledge About Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Basis

2.2. Presentation of Results

3. Results

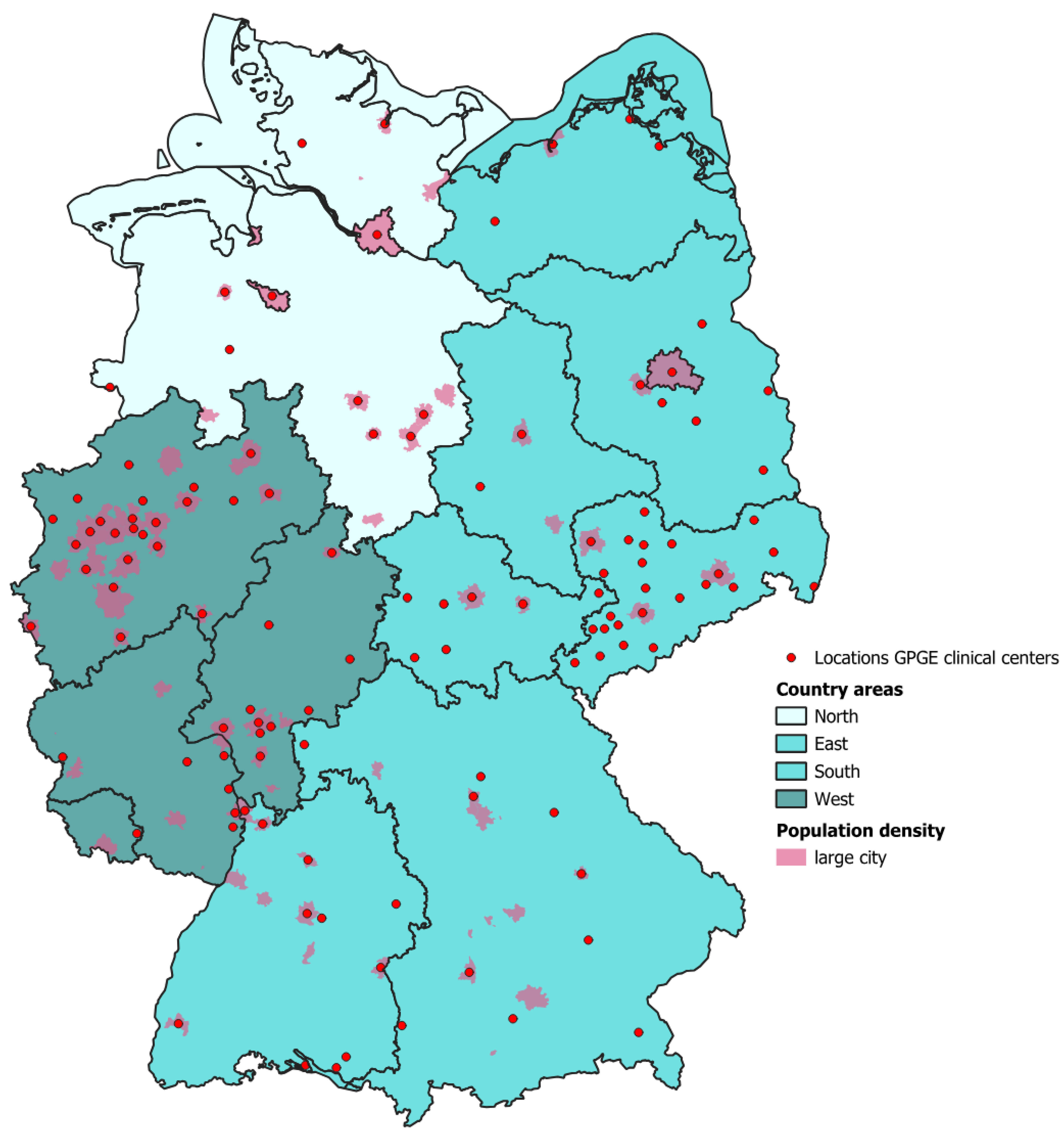

3.1. General Information About the Participants of the Survey

3.2. Level of Knowledge of Patients and Parents of Patients on IBD Topics

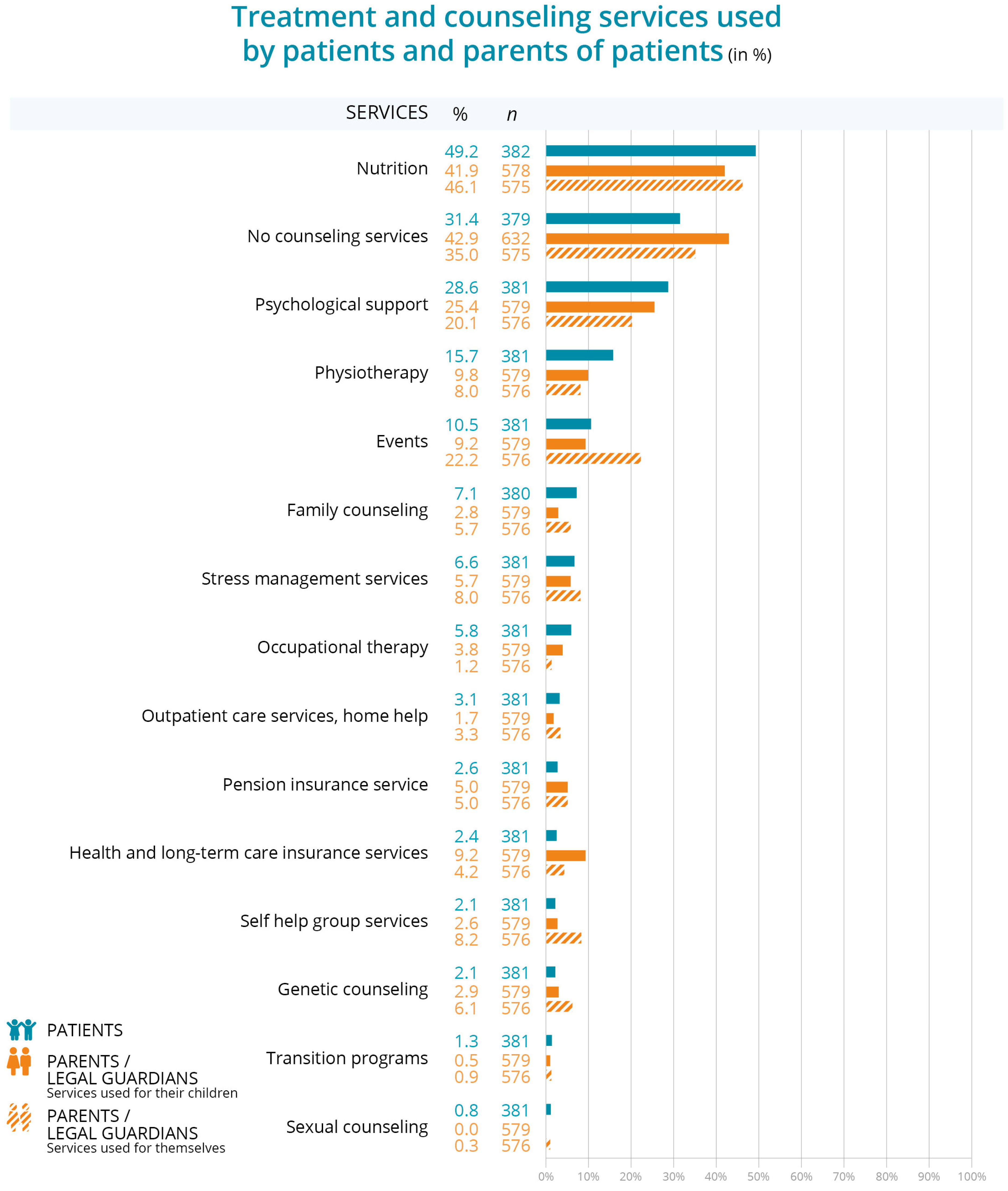

3.3. Treatment and Counseling Services Used by Patients and Parents of Patients

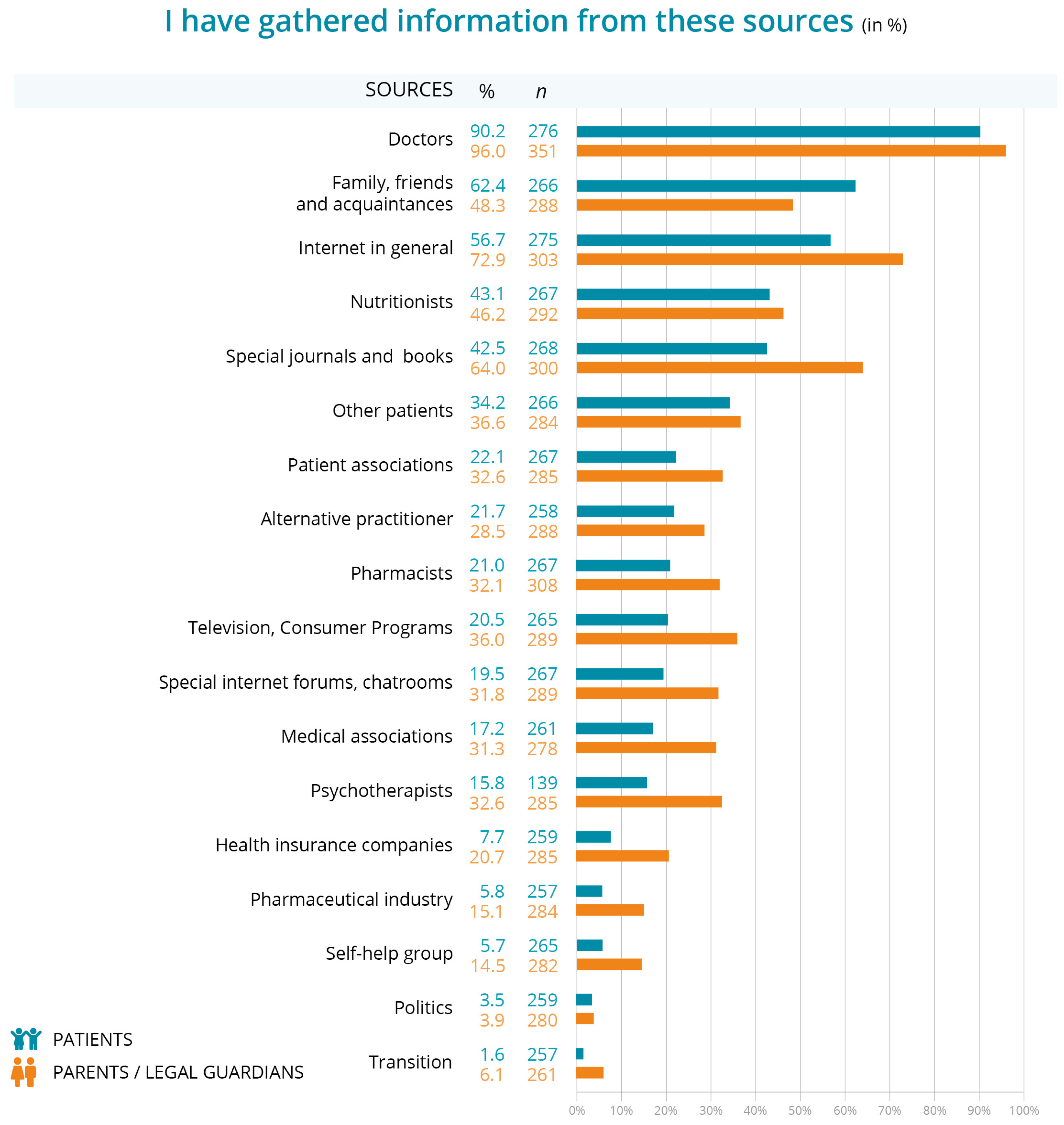

3.4. Trustworthy Sources of Information About IBD

3.5. Timing of Information on IBD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouhuys, M.; Lexmond, W.S.; van Rheenen, P.F. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022058037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, E.J.; Shanahan, M.L.; Joseph, E.; Reynolds, J.M.; Jimenez, D.E.; Abreu, M.T.; Carrico, A.W. The Relationship Between Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Narrative Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labanski, A.; Langhorst, J.; Engler, H.; Elsenbruch, S. Stress and the brain-gut axis in functional and chronic-inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases: A transdisciplinary challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 111, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisgaard, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Keefer, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Jess, T. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.C.H.; Durkin, L.K.; Greenley, R.N. Family Support is Associated with Fewer Adherence Barriers and Greater Intent to Adhere to Oral Medications in Pediatric IBD. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.-L.; Pomey, M.-P. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, D.; Williams, E.; Margolis, P.; Ruschman, J.; Bick, J.; Saeed, S.; Opipari, L. Improving pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) follow-up. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 2016, 5, u208961.w3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Markwart, H.; Bomba, F.; Muehlan, H.; Findeisen, A.; Kohl, M.; Menrath, I.; Thyen, U. Differential effect of a patient-education transition intervention in adolescents with IBD vs. diabetes. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.A.; Park, S.J.; Cheon, J.H. Improving the care of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients: Perspectives and strategies for IBD center management. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, L.; Radke, M.; Menzel, S.; Däbritz, J. Long-term implications of structured transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease into adult health care: A retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.; Salako, A.; Fofanova, T.; Kellermayer, R. Parental Education May Differentially Impact Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Risk. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bihari, A.; Olayinka, L.; Kroeker, K.I. Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Care: A Scoping Review. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, T.; Afzali, A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Practical Path to Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult Care. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurowski, J.A.; Philpott, J.R. The role of the transition clinic from pediatric to adult inflammatory bowel disease care. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 35, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóbi, L.; Prehoda, B.; Balogh, A.M.; Nagypál, P.; Kovács, K.; Miheller, P.; Iliás, Á.; Dezsőfi-Gottl, A.; Cseh, Á. Transition is associated with lower disease activity, fewer relapses, better medication adherence, and lower lost-to-follow-up rate as opposed to self-transfer in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease patients: Results of a longitudinal, follow-up, controlled study. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2024, 17, 17562848241252947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rheenen, P.F.; Aloi, M.; Assa, A.; Bronsky, J.; Escher, J.C.; Fagerberg, U.L.; Gasparetto, M.; Gerasimidis, K.; Griffiths, A.; Henderson, P.; et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J. Crohns. Colitis 2021, 15, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladouceur, M.; Calderon, J.; Traore, M.; Cheurfi, R.; Pagnon, C.; Khraiche, D.; Bajolle, F.; Bonnet, D. Educational needs of adolescents with congenital heart disease: Impact of a transition intervention programme. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 110, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, F.; Scarallo, L.; Nardone, O.M.; Aloi, M.; Alvisi, P.; Armuzzi, A.; Arrigo, S.; Bodini, G.; Calabrese, E.; Ceccarelli, L.; et al. Transition care in patients with IBD: The pediatric and the adult gastroenterologist’s perspective. Results from a national survey. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ye, B.D. Successful Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: What is the Key? Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, K.; Schumann, S.; Sander, C.; Däbritz, J.; de Laffolie, J. A Nationwide Survey on Patient Empowerment in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Germany. Children 2023, 10, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, K.; Schumann, S.; Sander, C.; Däbritz, J.; de Laffolie, J. Health Literacy of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Coping and Information Needs. Children 2024, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endres, E.-M. Soziale Medien in der Ernährungskommunikation: Relevanz und Potenziale; Zemdg Zentrum für Ethik der Medien und der Digitalen Gesellschaft: Munich, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-947443-09-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, L.N.; Ding, J. Optimizing the Transition and Transfer of Care in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2023, 52, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, K.; Pfeifer, M.; Manzey, P.; Koletzko, S. Chronisch entzündliche Darmerkrankungen—Die biopsychosoziale Realität im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2020, 63, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkey, M.; Baggett, A.B.; Tumin, D. Readiness for transition to adult health care among US adolescents, 2016–2020. Child Care. Health. Dev. 2022, 49, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawra, J.; Toulany, A.; Cohen, E.; Moore Hepburn, C.; Guttmann, A. Primary care interventions to improve transition of youth with chronic health conditions from paediatric to adult healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoultz, M.; Macaden, L.; Watson, A.J.M. Co-designing inflammatory bowel disease (Ibd) services in Scotland: Findings from a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruquie, S.S.; Parker, E.K.; Talbot, P. Evaluation of patient quality of life and satisfaction with home enteral feeding and oral nutrition support services: A cross-sectional study. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulou, M.-A.; Fradelos, E.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Malli, F.; Tsaras, K.; Christodoulou, N.G.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Quality of Life in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Importance of Psychological Symptoms. Cureus 2022, 14, e28502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krankenhausleistung. Available online: https://reimbursement.institute/glossar/krankenhausleistung/#:~:text=Gem%C3%A4%C3%9F%20%C2%A7%202%20KHEntgG%20sind,%2C%20sowie%20Unterkunft%20und%20Verpflegung%E2%80%9C (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Medforth, N.; Huntingdon, E. Still Lost in Transition? Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2018, 41, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Vogt, D.; Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; Hurrelmann, K. Health Literacy in Germany—Findings of a Representative Follow-up Survey. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Schaeffer, D. Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawthorne, A.B.; Glatter, J.; Blackwell, J.; Ainley, R.; Arnott, I.; Barrett, K.J.; Bell, G.; Brookes, M.J.; Fletcher, M.; Muhammed, R.; et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patient-reported quality assessment should drive service improvement: A national survey of UK IBD units and patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Responses in % | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Parents | |

| Level of knowledge (I feel informed about the transition) | ||

| Place of residence | n = 73 | n = 88 |

| Village | 38.4 | 28.4 |

| Small town | 52.1 | 58.0 |

| Large city | 9.6 | 13.6 |

| Region of residence | n = 74 | n = 89 |

| North | 12.2 | 9.0 |

| East | 23.0 | 16.9 |

| South | 27.0 | 29.2 |

| West | 37.8 | 45.9 |

| Information needs (I would like to know more about transition) | ||

| Place of residence | n = 164 | n = 67 |

| Village | 31.1 | 29.6 |

| Small town | 46.3 | 44.8 |

| Large city | 22.6 | 28.4 |

| Region of residence | n = 165 | n = 67 |

| North | 6.7 | 6.0 |

| East | 29.7 | 32.8 |

| South | 28.5 | 40.3 |

| West | 35.2 | 2.1 |

| Responses in % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Parents | ||

| I need information at diagnosis | I need information in the first year of diagnosis | ||

| Place of residence | n = 19 | Place of residence | n = 23 |

| Village | 21.0 | Village | 39.1 |

| Small town | 47.4 | Small town | 52.2 |

| Big city | 31.6 | Big city | 8.7 |

| Region of residence | n = 19 | Region of residence | n = 23 |

| North | 5.3 | North | 4.3 |

| East | 36.8 | East | 17.4 |

| South | 42.1 | South | 30.4 |

| West | 15.8 | West | 47.8 |

| I need information during the further disease course | I have no need for information | ||

| Place of residence | n = 433 | Place of residence | n = 41 |

| Village | 29.8 | Village | 22.0 |

| Small town | 47.3 | Small town | 58.5 |

| Big city | 22.9 | Big city | 19.5 |

| Region of residence | n = 433 | Region of residence | n = 41 |

| North | 11.5 | North | 9.8 |

| East | 22.9 | East | 7.3 |

| South | 30.7 | South | 29.3 |

| West | 34.9 | West | 53.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaul, K.; Schumann, S.; Felder, J.; Däbritz, J.; de Laffolie, J. Patient Empowerment Among Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Use of Counseling Services and Lack of Knowledge About Transition. Children 2025, 12, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050620

Kaul K, Schumann S, Felder J, Däbritz J, de Laffolie J. Patient Empowerment Among Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Use of Counseling Services and Lack of Knowledge About Transition. Children. 2025; 12(5):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050620

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaul, Kalina, Stefan Schumann, Jakob Felder, Jan Däbritz, and Jan de Laffolie. 2025. "Patient Empowerment Among Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Use of Counseling Services and Lack of Knowledge About Transition" Children 12, no. 5: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050620

APA StyleKaul, K., Schumann, S., Felder, J., Däbritz, J., & de Laffolie, J. (2025). Patient Empowerment Among Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Use of Counseling Services and Lack of Knowledge About Transition. Children, 12(5), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050620