Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Variables to Be Studied and Diagnostic Criteria

- Age;

- Sex;

- Type of school—public or private/charter;

- Geographical location—urban or rural;

- Education level of parents/guardians—elementary, secondary, or higher education.

- State of the dentition. A lesion presenting as an unmistakable cavity on the tooth surface was considered caries, as per the WHO 5th edition criteria [21]. Decayed (D), missing (M), and filled (F) teeth were recorded to calculate the prevalence of caries;

- DMFT index for primary dentition—the average of the sum of teeth with caries and filled teeth of all the schoolchildren examined (measured at 5–6 years old);

- DMFT index for permanent teeth—the mean of the sum of the numbers of teeth with caries, teeth absent due to caries, and filled teeth of all the schoolchildren examined (measured at 5–6, 12 and 15 years old);

- Prevalence of caries—the percentage of individuals with treated and active caries lesions (dmft/DMFT > 0), and the percentage of schoolchildren with active caries lesions (c/C > 0);

- Restorative index—the ratio of the total number of filled teeth to the total index under study (DMFT for permanent teeth or dmft for primary teeth), multiplied by 100. RI = [FT/(DMFT or dmft)] × 100;

- Bratthal’s SiC Index (Significant Caries Index). This is defined as the mean DMFT obtained from the third of the sample distribution with the highest caries scores. This was used as a complement to the DMFT;

- Sealed teeth. Sealants are considered a preventive intervention;

- Periodontal status was measured with the community periodontal index (CPI) and the number of healthy sextants in the 12- and 15-year-old cohorts. Six sites from each of the index teeth (16, 11, 26, 31, 36, and 46) were explored with the WHO periodontal probe and assessed as healthy (0), bleeding (1), or presenting dental calculus (2), recording only the highest value for each tooth;

- Urgency of intervention. This is determined according to the presence of caries, periodontal disease, or any other type of complication derived from them (0 = no treatment, 1 = preventive treatment, 2 = early treatment, and 3 = treatment for infection or pain);

- Frequency of brushing—determined via responses to the survey question (Never (0), <than once a day (1), once a day (2), 2 or more times per day (3), or NR (No Response)/DK (Don’t Know)) (4);

- Perception of health status. This was derived from answers to the question how would you describe the health of your teeth? 1 = excellent; 2 = very good; 3 = good; 4 = fair; 5 = poor; 6 = very poor; 9 = I do not know.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Sample

3.2. Variables Related to Caries Disease

- Primary dentition

- Permanent dentition

- Primary dentition

- Permanent dentition

3.3. Variables Related to Periodontal Disease

3.4. Analysis of the Urgency of Intervention

3.5. Analysis of Brushing Frequency

3.6. Analysis of Oral Health Perceptions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| DMFT | Decayed (D), Missing (M), and Filled (F) for permanent Teeth. |

| dmft | Decayed (D), Missing (M), and Filled (F) for primary teeth. |

References

- Petersen, P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century—The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31 (Suppl. S1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Dutt, U.; Radenkov, I.; Jain, S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: Actions, discussion and implementation. Oral Dis. 2023, 30, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, B.M.; Silla, A.J.; Díaz, C.E.; Peidró, C.E.; Martinicorena, C.F.; Delgado, E.A.; Santos, G.G.; Olivares, H.G.; Oliveira, L.M.; Beneyto, M.Y.; et al. Encuesta de Salud Oral 2020 [Internet]. Volume 25. 2020. Available online: www.rcoe.es (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ruber, P.T.; Calvo, J.C.L.; Abraham, J.M.Q.; Pérez, M.B. Encuesta de Salud Bucodental en Escolares de las Islas Baleares 2005; Conselleria de Salut i Consum, Servei de Salut de les Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zanella-Calzada, L.A.; Galvan-Tejada, C.E.; Chavez-Lamas, N.M.; Rivas-Gutierrez, J.; Magallanes-Quintanar, R.; Celaya-Padilla, J.M.; Galván-Tejada, J.I.; Gamboa-Rosales, H. Deep Artificial Neural Networks for the Diagnostic of Caries Using Socioeconomic and Nutritional Features as Determinants: Data from NHANES 2013–2014. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E.; Kwan, S. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes—The case of oral health. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2011, 39, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, B.W.; Rodrigues, P.H.; Kramer, P.F.; Vítolo, M.R.; Feldens, C.A. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.R.F.; Vidal, S.A.; de Goes, P.S.A.; Bandeira, P.F.R.; Filho, J.E.C. Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Oral Health Factors in Maternal and Child Health: An Interventional and Associative Study from the Network Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Naing, N.N.; Wan-Arfah, N.; de Abreu, M.H.N.G. Demographic and Habitual Factors of Periodontal Disease among South Indian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharyar, S.A.; Bernabé, E.; Delgado-Angulo, E.K. The Intersections of Ethnicity, Nativity Status and Socioeconomic Position in Relation to Periodontal Status: A Cross-Sectional Study in London, England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser-Ammann, P.; Lussi, A.; Bürgin, W.; Leisebach, T. Dental knowledge and attitude toward school dental-health programs among parents of kindergarten children in Winterthur. Swiss Dent. J. 2014, 124, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.M.; Lo, E.C.; Zhi, Q.H.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, Y.; Lin, H.C. Factors related to children’s caries: A structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, A.R.; Mialhe, F.L.; Tde, S.B.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M. Influence of family environment on children’s oral health: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2013, 89, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendicke, F.; Dorfer, C.E.; Schlattmann, P.; Page, L.F.; Thomson, W.M.; Paris, S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulton, R.; Caspi, A.; Milne, B.J.; Thomson, W.M.; Taylor, A.; Sears, M.R.; Moffitt, T.E. Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: A life-course study. Lancet 2002, 360, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M.J.; Vanobbergen, J.S.N.; Martens, L.C.; De Visschere, L.M.J. Socioeconomic inequalities in caries experience, care level and dental attendance in primary school children in Belgium: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, 015042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas Martín, M.Á. Influencia de las desigualdades sociales en salud en la mortalidad de la población rural y urbana en España, 2007–2013. Semergen 2020, 46, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doescher, M.; Keppel, G. Dentist Supply, Dental Care Utilization, and Oral Health Among Rural and Urban US Residents; Final report 135; WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, L.K.; Hallonsten, A.L.; Koch, G. Oral health in pre-school children living in Sweden. Part III—A longitudinal study. Risk analyses based on caries prevalence at 3 years of age and immigrant status. Swed Dent. J. 1999, 23, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, K.B.; O’Rourke, P.K. Social and behavioural determinants of early childhood caries. Aust. Dent. J. 2003, 48, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, I.; Vallejos, D.; Cuesta, R.; Domínguez, J.; Tomás, P.; López-Safont, N. Prevalence of oral diseases and influence of the presence of overweight/obesity in the school population of Mallorca. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, T.; Mahdi, S.S.; Khawaja, M.; Allana, R.; Amenta, F. Relationship between Socioeconomic Inequalities and Oral Hygiene Indicators in Private and Public Schools in Karachi: An Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrino, B.; Grasso, D.; Llaneras, K. Rich Schools, Poor Schools? How Private and Public Schools Segregate by Social Class. El País, 4 October 2019. Available online: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2019/10/04/escuela-de-ricos-escuela-de-pobres-como-la-concertada-y-la-publica-segregan-por-clase-social.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- PISA 2015. Programa Para la Evaluación Internacional de los Alumnos. Informe Español. Available online: www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/evaluaciones-internacionales/pisa/pisa-2015.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Lešić, S.; Dukić, W.; Kriste, Z.Š.; Tomičić, V.; Kadić, S. Caries prevalence among schoolchildren in urban and rural Croatia. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacaman, R.A.; Bustos, I.P.; Bazán, P.; Mariño, R.J. Oral health disparities among adolescents from urban and rural communities of central Chile. Rural Remote Health 2018, 18, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbatova, M.A.; Gorbatova, L.N.; Pastbin, M.U.; Grjibovski, A.M. Urban-rural differences in dental caries experience among 6-year-old children in the Russian north. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, A.R.; Salazar, O.M. Índice significante de caries (SIC) en niños y niñas escolares de 12 años de edad en Costa Rica. Odovtos-Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2007, 9, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aqeeli, A.; Alsharif, A.T.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M.; Bakeer, H. Caries prevalence and severity in association with sociodemographic characteristics of 9-to-12-year-old school children in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Stratum | Population Centers | Urban Rural |

|---|---|---|

| Second stratum | School types | Public Charter/Private |

| Third stratum | Age groups | 5–6 years old (1st-grade elementary) 12 years old (6th-grade elementary) 15 years old (4th-year secondary) |

| 1st Grade Elementary (5–6 Years Old) n = 255 | 6th Grade Elementary (12 Years Old) n = 230 | 4th Year Secondary (15 Years) n = 233 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Male | 144 | 56.47 | 125 | 54.35 | 112 | 48.06 | 381 | 53.06 |

| Female | 111 | 43.53 | 105 | 46.65 | 121 | 51.93 | 337 | 46.94 | |

| Type of school | Public | 177 | 69.4 | 159 | 69.1 | 190 | 81.5 | 526 | 73.3 |

| Private/Charter | 78 | 30.6 | 71 | 30.9 | 43 | 18.5 | 192 | 26.7 | |

| Geographic location | Urban | 163 | 63.9 | 140 | 60.9 | 101 | 43.3 | 404 | 56.3 |

| Rural | 92 | 36.1 | 90 | 39.1 | 132 | 56.7 | 314 | 43.7 | |

| n | Prevalence of Caries (%) | Prevalence of Active Caries Lesions (%) | Caries Index (Dmft/DMFT ± SD) | Restorative Index (RI ± SE) | Significant Caries Index (SiC ± SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–6 years old, primary | 255 | p-Value (Chi-square) | p-Value (Chi-square) | p-Value (Student’s t) | p-Value (Student’s t) | p-Value (Student’s t) | |||||

| Boys | 144 | 50 (34.7%) | 0.044 * | 36 (25%) | 0.019 * | 1.1250 ± 2.301 | 0.024 * | 36.748 ± 6.355 | 0.563 | - | - |

| Girls | 111 | 52 (46.8%) | 43 (38.7%) | 1.819 ± 2.580 | 31.833 ± 5.620 | - | - | ||||

| Public school | 177 | 77 (43.5%) | 0.085 | 61 (34.5%) | 0.070 | 1.598 ± 2.536 | 0.092 | 33.292 ± 4.796 | 0.694 | - | - |

| Private school/charter | 78 | 25 (32.1%) | 18 (23.1%) | 1.038 ± 2.194 | 37.171 ± 8.985 | - | - | ||||

| Urban school | 163 | 61 (37.4%) | 0.264 | 46 (28.2%) | 0.205 | 1.380 ± 2.477 | 0.130 | 35.267 ± 5.457 | 0.769 | - | - |

| Rural school | 92 | 41 (44.6%) | 33 (35.9%) | 1.510 ± 2.401 | 32.718 ± 6.723 | - | - | ||||

| 5–6 years old, permanent | 255 | ||||||||||

| Boys | 144 | 7 (4.9%) | 0.044 * | 6 (4.2%) | 0.068 | 0.0833 ± 0.4345 | 0.086 | 21.4286 ± 14.869 | 0.848 | 0.212 ± 0.689 | 0.132 |

| Girls | 111 | 13 (11.7%) | 11 (9.9%) | 0.198 ± 0.629 | 17.948 ± 10.415 | 0.473 ± 0.892 | |||||

| Public school | 177 | 14 (7.9%) | 0.953 | 11 (6.2%) | 0.663 | 0.152 ± 0.597 | 0.385 | 23.809 ± 11.284 | 0.408 | 0.338 ± 0.871 | 0.851 |

| Private school/charter | 78 | 6 (7.7%) | 6 (7.7%) | 0.087 ± 0.329 | 8.333 ± 8.333 | 0.300 ± 0.470 | |||||

| Urban school | 163 | 16 (9.8%) | 0.119 | 14 (8.6%) | 0.101 | 0.171 ± 0.614 | 0.124 | 17.708 ± 8.801 | 0.736 | 0.695 ± 0.973 | 0.009 * |

| Rural school | 92 | 4 (4.3%) | 3 (3.3%) | 0.065 ± 0.324 | 25.000 ± 25.000 | 0.193 ± 0.673 | |||||

| 12 years old | 230 | ||||||||||

| Boys | 125 | 31 (24.8%) | 0.336 | 13 (10.4%) | 0.491 | 0.552 ± 1.167 | 0.710 | 65.053 ± 8.165 | 0.810 | 1.815 ± 1.486 | 0.498 |

| Girls | 105 | 32 (30.5%) | 14 (13.3%) | 0.609 ± 1.1643 | 62.239 ± 8.316 | 1.589 ± 1.427 | |||||

| Public school | 159 | 49 (30.8%) | 0.081 | 24 (15.1%) | 0.018 * | 0.6918 ± 1.27 | 0.026 * | 56.802 ± 6.824 | 0.026 * | 1.963 ± 1.465 | 0.011 * |

| Private school/charter | 71 | 14 (19.7%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0.323 ± 0.824 | 87.500 ± 7.752 | 1.045 ± 1.214 | |||||

| Urban school | 140 | 36 (25.7%) | 0.477 | 14 (10%) | 0.307 | 0.4857 ± 1.042 | 0.133 | 65.740 ± 7.656 | 0.676 | 1.900 ± 1.295 | 0.341 |

| Rural school | 90 | 27 (30%) | 13 (14.4%) | 0.722 ± 1.324 | 60.802 ± 8.971 | 1.574 ± 1.542 | |||||

| 15 years old | 233 | ||||||||||

| Boys | 112 | 47 (42%) | 0.298 | 14 (12.5%) | 0.827 | 1.084 ± 1.831 | 0.978 | 72.553 ± 6.221 | 0.366 | 3.114 ± 2.111 | 0.249 |

| Girls | 121 | 59 (48.8%) | 14 (11.6%) | 1.074 ± 1.472 | 79.548 ± 4.762 | 2.651 ± 1.395 | |||||

| Public school | 190 | 93 (48.9%) | 0.026 * | 25 (13.2%) | 0.260 | 1.178 ± 1.724 | 0.048 * | 76.379 ± 4.109 | 0.963 | 2.871 ± 1.809 | 0.854 |

| Private school/charter | 43 | 13 (30.2%) | 3 (7%) | 0.627 ± 1.195 | 76.923 ± 10.764 | 2.75 ± 1.281 | |||||

| Urban school | 101 | 33 (32.7%) | <0.001 * | 8 (7.9%) | 0.093 | 0.673 ± 1.225 | <0.001 * | 80.303 ± 6.424 | 0.500 | 2.293 ± 1.353 | 0.039 * |

| Rural school | 132 | 73 (55.3%) | 20 (15.2%) | 1.386 ± 1.860 | 74.703 ± 4.744 | 3.156 ± 1.880 | |||||

| n | Prevalence of Caries (%) | Prevalence of Active Caries Lesions (%) | p | Caries Index Dmft/DMFT ± SD | p | Restorative Index RI ± SE | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

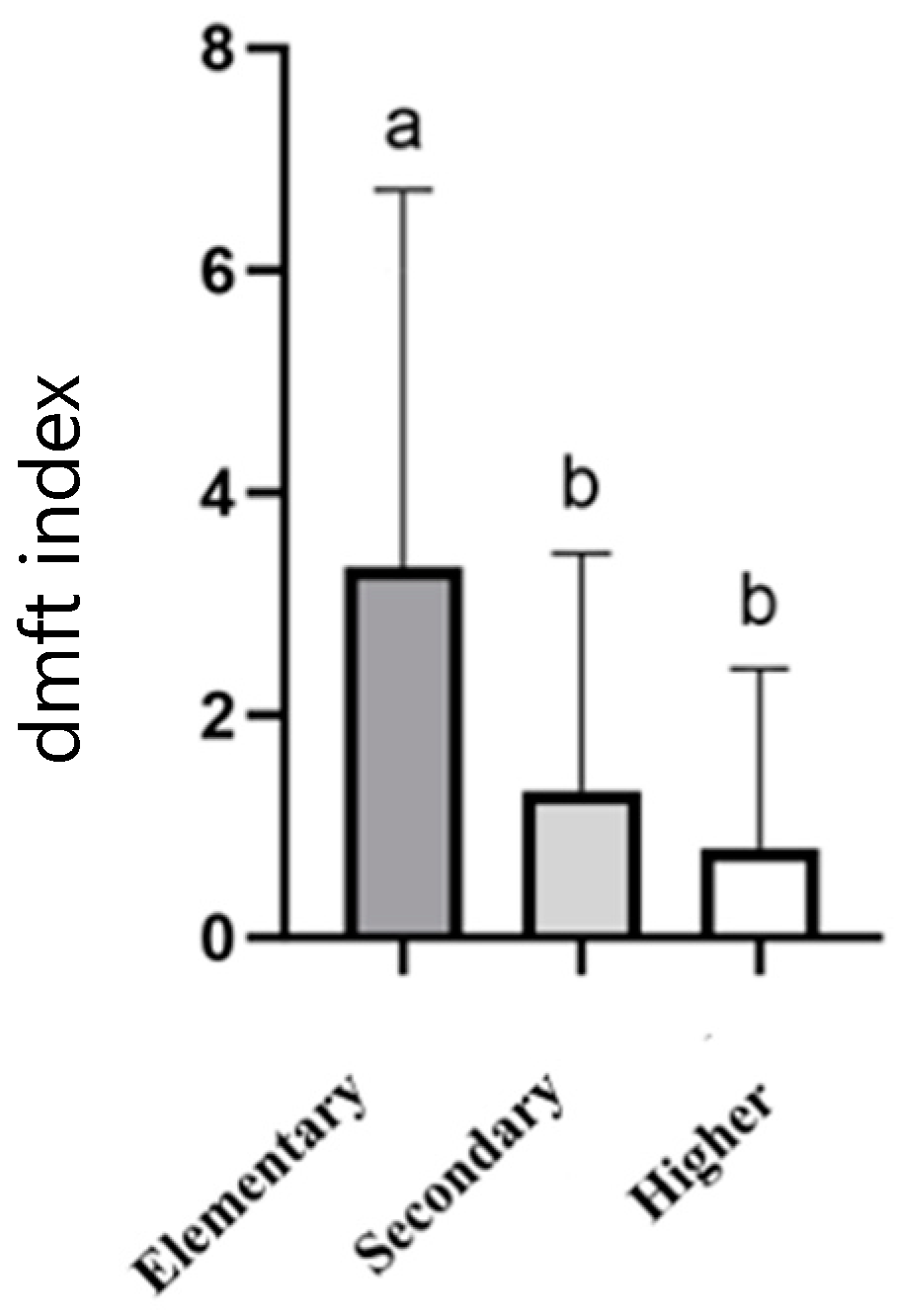

| 5–6 years old, primary | 255 | % | p-Value (Chi-square) | p-Value (Chi-square) | p-Value (ANOVA) | p-Value (ANOVA) | |||

| 1. Elementary | 12 | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (50%) | 3.333 ± 3.393 | 40.71 ± 14.64 | ||||

| 2. Secondary | 31 | 14 (45.2%) | 0.50 | 10 (32.3%) | 0.093 | 1.322 ± 2.135 | 0.001 * | 28.571 ± 12.529 | 0.562 |

| 3. Higher | 50 | 15 (30%) | 10 (20%) | 0.800 ± 1.616 | 46.944 ± 12.256 | ||||

| Unknown | 125 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5–6 years old, permanent | 255 | ||||||||

| 1. Elementary | 12 | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.083 ± 0.288 | 0 | - | |||

| 2. Secondary | 31 | 2 (6.5%) | 0.793 | 1 (6.5%) | 0.793 | 0.0645 ± 0.249 | 0.969 | 0 | - |

| 3. Higher | 50 | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 0.060 ± 0.313 | 0 | - | |||

| Unknown | 125 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

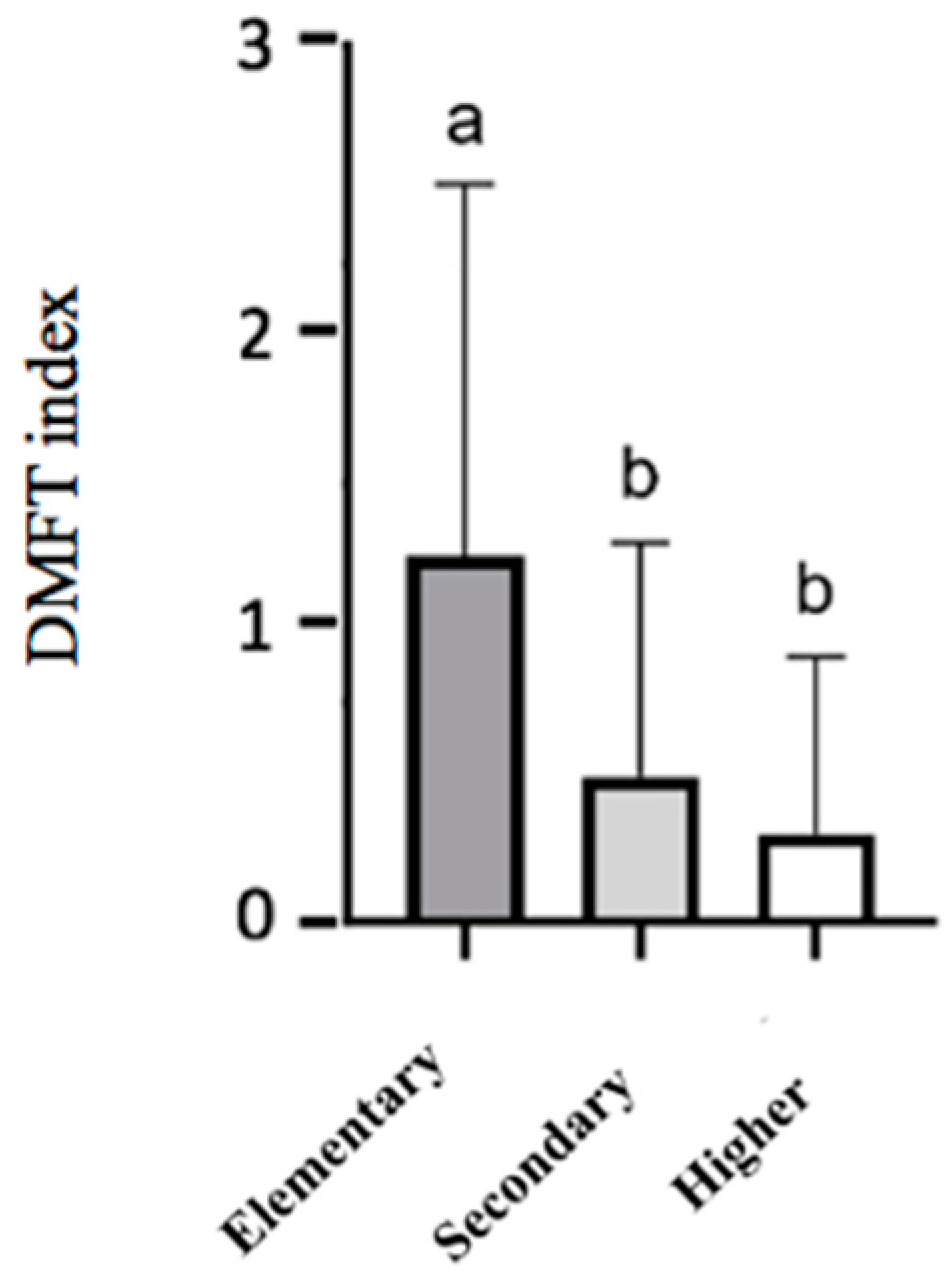

| 12 years old | 230 | ||||||||

| 1. Elementary | 12 | 6 (50%) | 5 (41.7%) | 1.333 ± 1.669 | 27.777 ± 18.087 | ||||

| 2. Secondary | 40 | 13 (32.5%) | 0.033 * | 3 (7.5%) | <0.001 * | 0.650 ± 1.166 | 0.010 * | 76.923 ± 12.162 | 0.055 |

| 3. Higher | 85 | 16 (18.8%) | 5 (5.9%) | 0.364 ± 0.884 | 75.000 ± 10.206 | ||||

| Unknown | 72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 years old | 233 | ||||||||

| 1. Elementary | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 0 | 0.750 ± 1.164 | 100 | ||||

| 2. Secondary | 55 | 31 (56.4%) | 0.103 | 10 (18.2%) | 0.083 | 1.363 ± 1.637 | 0.196 | 72.688 ± 7.378 | 0.438 |

| 3. Higher | 143 | 57 (39.9%) | 12 (8.4%) | 0.916 ± 1.629 | 79.678 ± 5.028 | ||||

| Unknown | 21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallejos, D.; Coll, I.; López-Safont, N. Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2025, 12, 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040527

Vallejos D, Coll I, López-Safont N. Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study. Children. 2025; 12(4):527. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040527

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallejos, Daniela, Irene Coll, and Nora López-Safont. 2025. "Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study" Children 12, no. 4: 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040527

APA StyleVallejos, D., Coll, I., & López-Safont, N. (2025). Association Between the Oral Health Status and Sociodemographic Factors Among 5–15-Year-Old Schoolchildren from Mallorca, Spain—A Cross-Sectional Study. Children, 12(4), 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040527