Sleep Habits and Disorders in School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Parental Questionnaires

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population Characteristics and Selection Criteria

2.2. Questionnaire Structure

- Disorders of Initiating and Maintaining Sleep (DIMS): assessment of difficulties falling asleep, frequent awakenings, and trouble resuming sleep.

- Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SBD): exploration of snoring, apnea [8]., and breathing difficulties.

- Disorders of Arousal (DA): evaluation of phenomena such as sleepwalking, nightmares, and confusional arousals.

- Sleep–Wake Transition Disorders (SWTD): analysis of involuntary body movements, teeth grinding (bruxism), and abnormal behaviors during sleep onset.

- Disorders of Excessive Somnolence (DOES): investigation of difficulties waking up, morning fatigue, excessive daytime sleepiness, and sudden sleep episodes. As highlighted in recent research, excessive daytime sleepiness and difficulties in sleep–wake regulation can significantly impact overall well-being and quality of life in affected individuals [6].

- Sleep Hyperhidrosis (SHY): measurement of excessive sweating during sleep.

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.4. Data Analysis

- Compute specific scores for each sleep disorder category by summing the items associated with each dimension.

- Determine the total SDSC score, indicative of the overall severity of sleep disorders.

- Identify recurring patterns and analyze significant deviations from SDSC normative values.

- Examine correlations between sleep dimensions and daytime consequences (e.g., fatigue, sleepiness).

3. Results

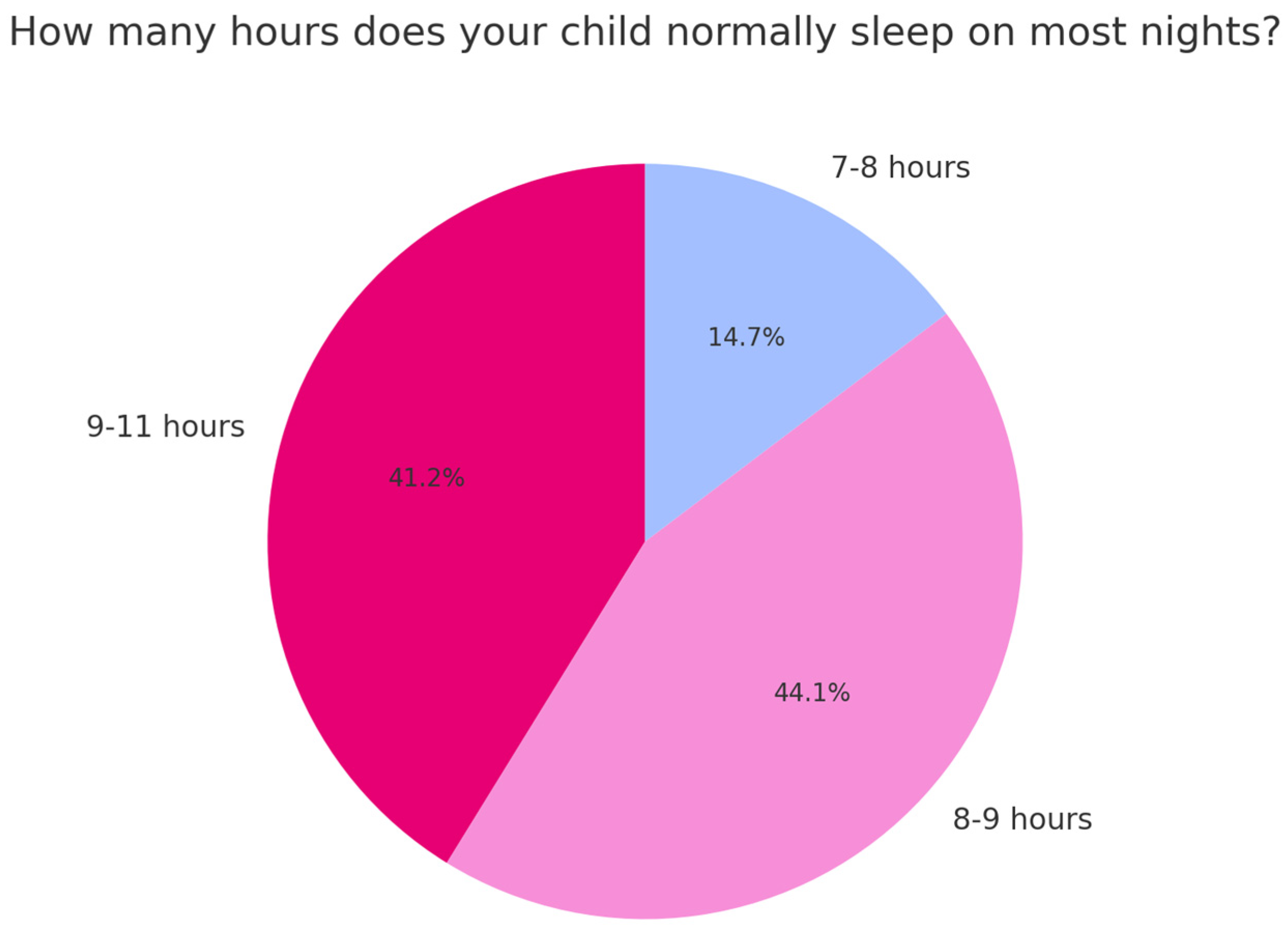

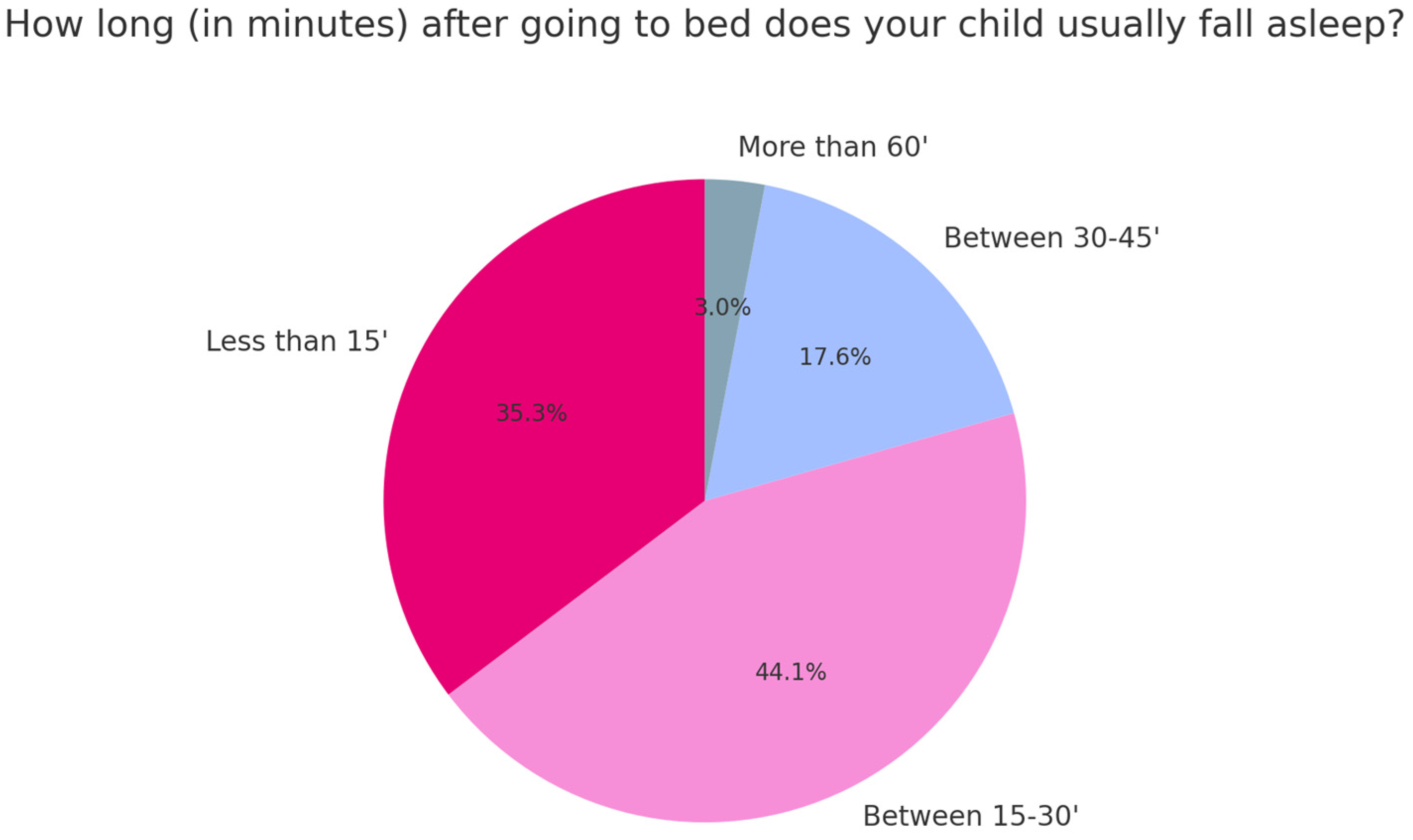

Sample Characteristics

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirshkowitz, M. Normal human sleep: An overview. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 88, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depner, C.M.; Stothard, E.R.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poza, J.J.; Pujol, M.; Ortega-Albás, J.J.; Romero, O. Insomnia Study Group of the Spanish Sleep Society (SES). Melatonin in sleep disorders. Neurologia 2022, 37, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porkka-Heiskanen, T.; Strecker, R.E.; McCarley, R.W. Brain site-specificity of extracellular adenosine concentration changes during sleep deprivation and spontaneous sleep: An in vivo microdialysis study. Neuroscience 2000, 99, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, D.; Dutta, D.; Chittawar, S.; Kalra, S. Sleep disorders in type 2 diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 21, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Varallo, G.; Franceschini, C.; Rapelli, G.; Zenesini, C.; Baldini, V.; Baccari, F.; Antelmi, E.; Pizza, F.; Vignatelli, L.; Biscarini, F.; et al. Navigating narcolepsy: Exploring coping strategies and their association with quality of life in patients with narcolepsy type 1. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trosman, I.; Ivanenko, A. Classification and epidemiology of sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 30, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignotti, D.; De Stefani, A.; Mezzofranco, L.; Bruno, G.; Gracco, A. Multidisciplinary approach in a 12-year-old patient affected by severe obstructive sleep apnea: A case-report. Sleep Med. Res. 2019, 10, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roen Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social Jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobaldini, E.; Costantino, G.; Solbiati, M.; Cogliati, C.; Kara, T.; Nobili, L.; Montano, N. Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Ottaviano, S.; Guidetti, V.; Romoli, M.; Innocenzi, M.; Cortesi, F.; Giannotti, F. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res. 1996, 5, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, D.W.; Ris, M.D.; Kramer, M.E.; Long, E.; Amin, R. The association between sleep-disordered breathing, academic grades, and cognitive functioning in children. Sleep 2010, 33, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, L.; Andreose, A.; Bacaro, V.; Giovagnoli, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Natale, V.; Crocetti, E. External validity of the reduced Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents: An actigraphic study. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Question | Never (%) | Occasionally 1–2 Times Per Month (%) | Sometimes 1–2 Per Week (%) | Often (%) | Always, Every Day (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The child goes to bed unwillingly | 14.7 | 32.4 | 32.4 | 20.6 | 14.7 |

| The child has difficulty falling asleep | 14.7 | 50 | 29.4 | 5.9 | 0 |

| The child feels anxious or scared when falling asleep | 50 | 32.4 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 0 |

| The child jerks or makes sudden movements of certain parts of the body while falling asleep | 50 | 29.4 | 14.7 | 5.9 | 0 |

| The child shows repetitive actions such as rocking or banging his head while falling asleep | 91.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0 |

| The child experiences vivid dream scenes as he falls asleep | 76.5 | 20.5 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 |

| The child sweats excessively while falling asleep | 64.7 | 20.6 | 12.5 | 8.3 | 4.2 |

| The child wakes up more than twice and during the night | 47.1 | 32.4 | 14.7 | 0 | 0 |

| If the child wakes up during the night, he has difficulty falling back asleep | 47.1 | 38.3 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 |

| The baby moves continuously during sleep | 23.5 | 23.5 | 35.3 | 0 | 11.8 |

| The child gasps or is unable to breathe during sleep | 79.4 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The child snores. | 38.2 | 44.1 | 8.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Baby sweats excessively during the night | 47.1 | 32.4 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 0 |

| Have you noticed episodes of sleepwalking in the child? (gets out of bed, walks) | 88.2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Have you observed the baby talking in his sleep? | 42.4 | 42.2 | 12.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Child grinds teeth during sleep | 58.8 | 11.8 | 20.6 | 8.8 | 0 |

| The child wakes up screaming or confused in such a way that you can’t communicate with him but has no memory of these events the next morning. | 70.6 | 23.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The child has nightmares that he does not remember the next day. | 35.3 | 55.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The child has difficulty waking up in the morning. | 29.4 | 32.4 | 26.5 | 0 | 0 |

| The child wakes up feeling tired in the morning. | 38.2 | 41.2 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 0 |

| The child feels unable to move or feels paralyzed when he wakes up in the morning. | 88.2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The child has daytime sleepiness. | 72.7 | 15.2 | 12.1 | 0 | 0 |

| The child suddenly falls asleep in inappropriate situations. | 85.3 | 14.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mezzofranco, L.; Agostini, L.; Boutarbouche, A.; Melato, S.; Zalunardo, F.; Franco, A.; Gracco, A. Sleep Habits and Disorders in School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Parental Questionnaires. Children 2025, 12, 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040489

Mezzofranco L, Agostini L, Boutarbouche A, Melato S, Zalunardo F, Franco A, Gracco A. Sleep Habits and Disorders in School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Parental Questionnaires. Children. 2025; 12(4):489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040489

Chicago/Turabian StyleMezzofranco, Luca, Ludovica Agostini, Ayoub Boutarbouche, Sofia Melato, Francesca Zalunardo, Anna Franco, and Antonio Gracco. 2025. "Sleep Habits and Disorders in School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Parental Questionnaires" Children 12, no. 4: 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040489

APA StyleMezzofranco, L., Agostini, L., Boutarbouche, A., Melato, S., Zalunardo, F., Franco, A., & Gracco, A. (2025). Sleep Habits and Disorders in School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Parental Questionnaires. Children, 12(4), 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040489