Influences of Maternal, Child, and Household Factors on Diarrhea Management in Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

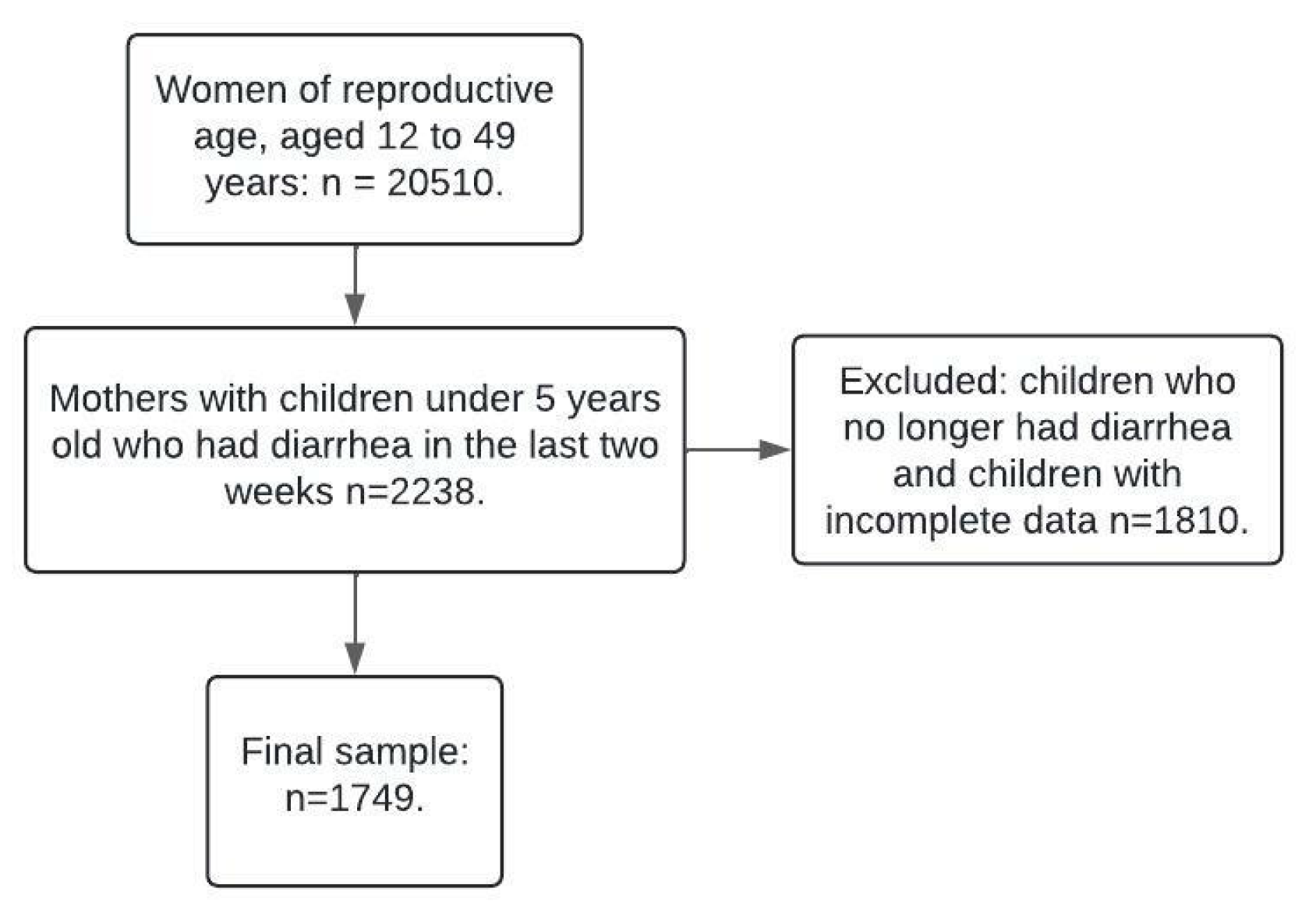

2.1. Study Size

2.2. Study Design and Scope

2.3. Variables and Measurement

2.4. Statistical Modeling

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Momoh, F.E.; Olufela, O.E.; Adejimi, A.A.; Roberts, A.A.; Oluwole, E.O.; Ayankogbe, O.O.; Onajole, A.T. Mothers’ Knowledge, Attitude and Home Management of Diarrhoea among Children under Five Years Old in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2022, 14, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diouf, K.; Tabatabai, P.; Rudolph, J.; Marx, M. Diarrhoea Prevalence in Children under Five Years of Age in Rural Burundi: An Assessment of Social and Behavioural Factors at the Household Level. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 24895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarrheal Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Shewangizaw, B.; Mekonen, M.; Fako, T.; Hoyiso, D.; Borie, Y.A.; Yeheyis, T.; Kassahun, G. Knowledge and Attitude on Home-Based Management of Diarrheal Disease among Mothers/Caregivers of under-Five Children at a Tertiary Hospital in Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2023, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Workie, H.M.; Sharifabdilahi, A.S.; Addis, E.M. Mothers’ Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards the Prevention and Home-Based Management of Diarrheal Disease among under-Five Children in Diredawa, Eastern Ethiopia, 2016: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, G.; Murugan, R.; Bedada, T.; Bacha, G.; Bekele, G. Home-Based Management Practice of Diarrhea in under 5 Years Old Children and Associated Factors among Caregivers in Ginchi Town, Oromia Region, West Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221095727. [Google Scholar]

- Merga, N.; Alemayehu, T. Knowledge, Perception, and Management Skills of Mothers with under-Five Children about Diarrhoeal Disease in Indigenous and Resettlement Communities in Assosa District, Western Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, X.; Calderón, N.; Solis, O.; Jimbo-Sotomayor, R. Antibiotic Prescription Patterns in Children Under 5 Years of Age With Acute Diarrhea in Quito-Ecuador. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231196110. [Google Scholar]

- Galárraga, O.; Quijano-Ruiz, A.; Faytong-Haro, M. The Effects of Mobile Primary Health Teams: Evidence from the Médico Del Barrio Strategy in Ecuador. World Dev. 2024, 181, 106659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mora, F.X.; Avilés-Reyes, R.X.; Guerrero-Latorre, L.; Fernández-Moreira, E. Atypical Enteropathogenic Escherichia Coli (aEPEC) in Children under Five Years Old with Diarrhea in Quito (Ecuador). Int. Microbiol. 2016, 19, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, L.; Smith, S.M.; Jesser, K.J.; Paez, M.; Ortega, E.; Peña-Gonzalez, A.; Soto-Girón, M.J.; Hatt, J.K.; Sánchez, X.; Puebla, E. Distribution of Escherichia Coli Pathotypes along an Urban–Rural Gradient in Ecuador. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 109, 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, K.H.; Ribeiro, P.S.; Quist, B.K.; Rydbeck, B.V. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites in Young Quichua Children in the Highlands of Rural Ecuador. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2007, 25, 399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Román-Zambrano, V.V.; González-Hernández, A. Malnutrition and Its Influence on Morbidity in Children Under Five Years of Age, Crucita Parish, Manabí. MQRInvestigar [Internet]. 30 October 2023, Volume 7, pp. 1393–1407. Available online: https://www.investigarmqr.com/ojs/index.php/mqr/article/view/766 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Vera, A.A.Z.; Vargas, D.M.Z.; Nieto, L.C.M. Nivel de Desnutrición a Partir de Las Medidas Antropométricas En Niños Menores de 5 Años. Polo Conoc. 2024, 9, 4196–4218. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Simbaña-Rivera, K.; Cevallos, G.; Gómez-Barreno, L.; Cevallos, D.; Lister, A.; Fernandez-Naranjo, R.; Ríos-Touma, B.; Vásconez-González, J.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S. Waterborne Diseases and Ethnic-Related Disparities: A 10 Years Nationwide Mortality and Burden of Disease Analysis from Ecuador. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1029375. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R.; Armijos, R.X.; Beidelman, E.T.; Rosenberg, M.; Margaret Weigel, M. Household Food and Water Insecurity and Its Association with Diarrhoea, Respiratory Illness, and Stunting in Ecuadorian Children under 5 Years. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2024, 20, e13683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ecuador—National Health and Nutrition Survey 2018—General Information. Available online: https://anda.inec.gob.ec/anda/index.php/catalog/891 (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Lucio, R.; Villacrés, N.; Henríquez, R. Sistema de salud de Ecuador. Salud Pública de México 2011, 53, s177–s187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaçan, C.Y.; Palloş, A.; Özkaya, G. Examining Knowledge and Traditional Practices of Mothers with Children under Five in Turkey on Diarrhoea According to Education Levels. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 674. [Google Scholar]

- Thiam, S.; Sy, I.; Schindler, C.; Niang-Diène, A.; Faye, O.; Utzinger, J.; Cissé, G. Knowledge and Practices of Mothers and Caregivers on Diarrhoeal Management among under 5-Year-Old Children in a Medium-Size Town of Senegal. Acta Trop. 2019, 194, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Saima, U.; Goni, M.A. Impact of Maternal Household Decision-Making Autonomy on Child Nutritional Status in Bangladesh. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, 509–520. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.R.K.; Bornee, F.A.; Chowdhury, H.A.; Billah, B.; Kader, M.; Rashid, M. Prevalence and Determinants of Diarrhea, Fever, and Coexistence of Diarrhea and Fever in Children under-Five in Bangladesh. Children 2023, 10, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane, M.; Vermaak, K. A Multilevel Analysis of Individual, Household and Community Level Predictors of Child Diarrhea in Eswatini. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.; Lattof, S.R.; Coast, E. Interventions to Provide Culturally-Appropriate Maternity Care Services: Factors Affecting Implementation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Målqvist, M.; Trygg, N.; Qian, X.; Ng, N.; Thomsen, S. What Interventions Are Effective on Reducing Inequalities in Maternal and Child Health in Low-and Middle-Income Settings? A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Claudine, U.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, E.-M.; Yong, T.-S. Association between Sociodemographic Factors and Diarrhea in Children under 5 Years in Rwanda. Korean J. Parasitol. 2021, 59, 61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wasihun, A.G.; Dejene, T.A.; Teferi, M.; Marugán, J.; Negash, L.; Yemane, D.; McGuigan, K.G. Risk Factors for Diarrhoea and Malnutrition among Children under the Age of 5 Years in the Tigray Region of Northern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207743. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.; Hubbard, S.; Brauer, M.; Ambelu, A.; Arnold, B.F.; Bain, R.; Bauza, V.; Brown, J.; Caruso, B.A.; Clasen, T. Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Handwashing with Soap on Risk of Diarrhoeal Disease in Children in Low-Income and Middle-Income Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2022, 400, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Adane, M.; Mengistie, B.; Medhin, G.; Kloos, H.; Mulat, W. Piped Water Supply Interruptions and Acute Diarrhea among Under-Five Children in Addis Ababa Slums, Ethiopia: A Matched Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181516. [Google Scholar]

- Bhavnani, D.; Goldstick, J.E.; Cevallos, W.; Trueba, G.; Eisenberg, J.N. Impact of Rainfall on Diarrheal Disease Risk Associated with Unimproved Water and Sanitation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nyamathi, A.; Jackson, D.; Carter, B.; Hayter, M. Creating Culturally Relevant and Sustainable Research Strategies to Meet the Needs of Vulnerable Populations. Contemp. Nurse 2012, 42, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martínez, H.; Habicht, J.-P. A Programme to Develop Culturally and Medically Sound Home Fluid Management of Children with Acute Diarrhoea. Food Nutr. Bull. 1996, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, D.B.; Sierra-Arevalo, L.; Caldwell Ashur, A.-C.; White, J.T.; Villa Torres, L. Spanish Translation and Cultural Adaptations of Physical Therapy Parent Educational Materials for Use in Neonatal Intensive Care. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.R. The Use of an Incentive to Improve Breastfeeding Outcomes: The Effectiveness of Offering a Free Family YMCA Membership to Increase Support Group Participation. J. Hum. Lact. 2022, 38, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nandi, A.; Megiddo, I.; Ashok, A.; Verma, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Reduced Burden of Childhood Diarrheal Diseases through Increased Access to Water and Sanitation in India: A Modeling Analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 180, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Slimming, P.A.; Carcamo, C.P.; Wright, C.J.; Lancha, G.; Zavaleta-Cortijo, C.; King, N.; Ford, J.D.; Garcia, P.J.; Harper, S.L. Diarrheal Disease and Associations with Water Access and Sanitation in Indigenous Shawi Children along the Armanayacu River Basin in Peru. Rural. Remote Health 2023, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gallandat, K.; Macdougall, A.; Jeandron, A.; Mufitini Saidi, J.; Bashige Rumedeka, B.; Malembaka, E.B.; Azman, A.S.; Bompangue, D.; Cousens, S.; Allen, E. Improved Water Supply Infrastructure to Reduce Acute Diarrhoeal Diseases and Cholera in Uvira, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Results and Lessons Learned from a Pragmatic Trial. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012265. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, R.; Talboys, S.; Vanderslice, J.; Stringer, K. Evaluation of a Village-Level Safe Water Treatment and Storage Intervention in Bassi Pathana, India. Ann. Glob. Health 2014, 80, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Clasen, T.; Garcia Parra, G.; Boisson, S.; Collin, S. Household-Based Ceramic Water Filters for the Prevention of Diarrhea: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Pilot Program in Colombia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 73, 790–795. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M.C.; Trinies, V.; Boisson, S.; Mak, G.; Clasen, T. Promoting Household Water Treatment through Women’s Self Help Groups in Rural India: Assessing Impact on Drinking Water Quality and Equity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e0044068. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z.A. Reaching the Unreached; Mobile Health Teams in Conflict Settings. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abua, U.J.; Igbudu, T.J.; Egwuda, L.; Yaakugh, G.J. Impact of Training of Primary Healthcare Workers on Integrated Community Case Management of Childhood Illnesses in North-West District of Benue State, Nigeria. J. Pharm. Bioresour. 2020, 17, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Total (%) | No Healthcare Attendance (9.9%) | Healthcare Attendance (90.1%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household-level variables | ||||

| Rural/Urban | ||||

| Rural | 976 (55.8%) | 113 (11.6% of Rural) | 863 (88.4% of Rural) | 0.008 |

| Urban | 773 (44.2%) | 60 (7.8% of Urban) | 713 (92.2% of Urban) | |

| Poverty Classification | ||||

| Non-poor | 1029 (58.8%) | 110 (10.7% of Non-poor) | 919 (89.3% of Non-poor) | 0.368 |

| Poor | 483 (27.6%) | 44 (9.1% of Poor) | 439 (90.9% of Poor) | |

| Extremely Poor | 237 (13.6%) | 19 (8.0% of Extremely Poor) | 218 (92.0% of Extremely Poor) | |

| Sanitary Facilities | ||||

| With Facilities | 1596 (91.3%) | 164 (10.3% of With Facilities) | 1432 (89.7% of With Facilities) | 0.082 |

| Without Facilities | 153 (8.7%) | 9 (5.9% of Without Facilities) | 144 (94.1% of Without Facilities) | |

| Water Source | ||||

| Improved Water | 1572 (89.9%) | 164 (10.4% of Improved Water) | 1408 (89.6% of Improved Water) | 0.024 |

| Unimproved Water | 177 (10.1%) | 9 (5.1% of Unimproved Water) | 168 (94.9% of Unimproved Water) | |

| Child-level variables | ||||

| Dehydration Indicator | ||||

| No Dehydration | 212 (12.1%) | 49 (23.1% of No Dehydration) | 163 (76.9% of No Dehydration) | <0.001 |

| Mild Dehydration | 509 (29.1%) | 63 (12.4% of Mild Dehydration) | 446 (87.6% of Mild Dehydration) | |

| Severe Dehydration | 1028 (58.8%) | 61 (5.9% of Severe Dehydration) | 967 (94.1% of Severe Dehydration) | |

| Age in Months | ||||

| 0–11 Months | 346 (19.8%) | 47 (13.6% of 0–11 Months) | 299 (86.4% of 0–11 Months) | 0.102 |

| 12–18 Months | 390 (22.3%) | 40 (10.3% of 12–18 Months) | 350 (89.7% of 12–18 Months) | |

| Maternal-level variables | ||||

| Educational Level | ||||

| None or Literacy Center | 21 (1.2%) | 6 (28.6% of None) | 15 (71.4% of None) | 0.003 |

| Basic Education | 668 (38.2%) | 58 (8.7% of Basic Education) | 610 (91.3% of Basic Education) | |

| Higher Education | 279 (16.0%) | 38 (13.6% of Higher Education) | 241 (86.4% of Higher Education) | |

| Race | ||||

| Mixed | 1264 (72.3%) | 122 (9.6% of Mixed) | 1142 (90.4% of Mixed) | 0.234 |

| Indigenous | 296 (16.9%) | 25 (8.4% of Indigenous) | 271 (91.6% of Indigenous) | |

| Afro | 103 (5.9%) | 13 (12.6% of Afro) | 90 (87.4% of Afro) |

| Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Received Healthcare Attendance | Received Healthcare Professional Attendance | Giving More Liquid | Change in Diet | Decreased Intake of Solids |

| Rural (Ref = Urban) | 1.345 | 0.926 | 1.080 | 1.260 * | 1.377 * |

| (0.276) | (0.120) | (0.148) | (0.159) | (0.268) | |

| Number of persons in the household (Ref = 2–3 people) | |||||

| 4–6 people | 1.584 ** | 0.891 | 0.965 | 1.113 | 1.178 |

| (0.337) | (0.131) | (0.148) | (0.155) | (0.292) | |

| 7–9 people | 2.006 ** | 1.116 | 1.259 | 1.048 | 2.033 ** |

| (0.617) | (0.224) | (0.263) | (0.207) | (0.625) | |

| 10+ people | 1.355 | 0.997 | 0.851 | 0.876 | 1.352 |

| (0.547) | (0.300) | (0.253) | (0.248) | (0.605) | |

| Poverty classification (Ref = not poor) | |||||

| Poor | 0.874 | 1.050 | 0.832 | 0.918 | 0.768 |

| (0.195) | (0.147) | (0.117) | (0.123) | (0.171) | |

| Extremely poor | 0.799 | 1.232 | 0.978 | 1.259 | 0.530 * |

| (0.280) | (0.274) | (0.231) | (0.276) | (0.194) | |

| Bad hand washing (Ref = good hand washing) | 1.079 | 0.888 | 0.751 | 0.688 * | 1.192 |

| (0.382) | (0.176) | (0.155) | (0.142) | (0.360) | |

| Sanitary facilities (Ref = no sanitary facilities) | 0.604 | 1.549 * | 0.898 | 1.471 | 0.832 |

| (0.265) | (0.386) | (0.231) | (0.365) | (0.332) | |

| Household income (Ref = no income) | |||||

| $501–$1000 | 0.929 | 0.980 | 1.034 | 0.837 | 0.999 |

| (0.207) | (0.136) | (0.148) | (0.110) | (0.218) | |

| $1001–$1500 | 0.708 | 1.106 | 1.094 | 1.146 | 0.901 |

| (0.204) | (0.237) | (0.235) | (0.236) | (0.292) | |

| $1501–$2000 | 1.279 | 0.839 | 1.535 | 1.517 | 1.396 |

| (0.600) | (0.228) | (0.478) | (0.428) | (0.556) | |

| $2001–$2500 | 0.560 | 0.873 | 0.833 | 1.208 | 1.791 |

| (0.266) | (0.314) | (0.296) | (0.404) | (0.750) | |

| $2501–$3000 | 0.626 | 1.160 | 1.169 | 1.272 | 0.448 |

| (0.401) | (0.579) | (0.594) | (0.617) | (0.470) | |

| $3001–$4000 | 0.490 | 0.834 | 1.724 | 0.948 | 0.650 |

| (0.248) | (0.405) | (0.835) | (0.390) | (0.492) | |

| $4000+ | 1.137 | 0.962 | 1.834 | 0.753 | 0.465 |

| (0.936) | (0.452) | (1.002) | (0.367) | (0.506) | |

| Age in months (Ref = 0–11) | |||||

| 12–18 months | 1.314 | 0.786 | 1.859 *** | 3.016 *** | 0.369 *** |

| (0.319) | (0.135) | (0.301) | (0.491) | (0.0902) | |

| 19–23 months | 2.366 ** | 0.479 *** | 2.182 *** | 4.359 *** | 0.479 ** |

| (0.796) | (0.0952) | (0.450) | (0.841) | (0.141) | |

| 24–30 months | 1.332 | 0.651 ** | 2.125 *** | 3.008 *** | 0.461 *** |

| (0.379) | (0.127) | (0.415) | (0.575) | (0.137) | |

| 31–35 months | 1.393 | 0.587 ** | 2.614 *** | 2.646 *** | 0.321 *** |

| (0.507) | (0.131) | (0.624) | (0.575) | (0.124) | |

| 36–42 months | 2.183 * | 0.685 | 2.258 *** | 3.358 *** | 0.365 *** |

| (0.904) | (0.158) | (0.527) | (0.762) | (0.130) | |

| 43–47 months | 0.886 | 0.875 | 2.692 *** | 3.027 *** | 0.442 ** |

| (0.330) | (0.238) | (0.799) | (0.800) | (0.177) | |

| 48–59 months | 1.217 | 0.634 ** | 2.964 *** | 3.911 *** | 0.158 *** |

| (0.359) | (0.132) | (0.628) | (0.785) | (0.0700) | |

| Order of child (Ref = first son) | |||||

| Second child | 0.779 | 0.989 | 0.685 * | 1.187 | 1.169 |

| (0.251) | (0.192) | (0.139) | (0.237) | (0.409) | |

| Third child | 0.628 | 3.017 | 0.883 | 2.176 | |

| (0.385) | (3.615) | (0.542) | (2.006) | ||

| Female (Ref = Male) | 1.145 | 0.940 | 1.019 | 1.088 | 1.089 |

| (0.197) | (0.101) | (0.112) | (0.113) | (0.185) | |

| Dehydrated (Ref = Hydrated) | |||||

| Mild dehydration | 1.980 *** | 1.379 * | 3.448 *** | 1.761 *** | 0.767 |

| (0.439) | (0.268) | (0.631) | (0.323) | (0.216) | |

| Severe dehydration | 4.227 *** | 2.039 *** | 3.897 *** | 3.248 *** | 0.922 |

| (0.921) | (0.376) | (0.671) | (0.563) | (0.237) | |

| Persistent diarrhea (Ref = Acute diarrhea) | 0.710 | 0.388 | 1.851 | 0.921 | |

| (0.821) | (0.258) | (1.647) | (1.101) | ||

| Race (Ref = Mestizo) | |||||

| Indigenous | 0.726 | 0.862 | 0.748 | 0.710 ** | 0.727 |

| (0.256) | (0.147) | (0.132) | (0.121) | (0.212) | |

| Afro | 0.709 | 0.686 | 0.772 | 0.639 ** | 0.525 |

| (0.242) | (0.159) | (0.175) | (0.145) | (0.238) | |

| Others | 0.620 | 0.589 ** | 1.177 | 0.495 *** | 0.730 |

| (0.213) | (0.158) | (0.330) | (0.126) | (0.312) | |

| Without education (Ref = without education) | |||||

| Basic education | 4.077 ** | 0.460 | 0.640 | 0.406 * | 1.768 |

| (2.313) | (0.290) | (0.347) | (0.209) | (1.886) | |

| Middle-/high-school education | 5.007 *** | 0.591 | 0.870 | 0.500 | 1.589 |

| (2.876) | (0.374) | (0.476) | (0.258) | (1.715) | |

| Higher education | 3.275 ** | 0.749 | 0.952 | 0.575 | 1.383 |

| (1.953) | (0.486) | (0.541) | (0.307) | (1.544) | |

| Marital status (Ref = Married/United) | |||||

| Separated | 1.021 | 1.017 | 1.346 | 0.750 | 1.154 |

| (0.291) | (0.193) | (0.278) | (0.141) | (0.351) | |

| Single | 1.249 | 0.834 | 0.835 | 0.690 ** | 1.280 |

| (0.331) | (0.136) | (0.139) | (0.110) | (0.306) | |

| Age in years (Ref = 12–17 years) | |||||

| 18–19 years | 0.697 | 0.713 | 0.868 | 0.498 ** | 1.077 |

| (0.366) | (0.263) | (0.304) | (0.175) | (0.527) | |

| 20–49 years | 1.235 | 0.789 | 1.126 | 1.011 | 0.667 |

| (0.617) | (0.261) | (0.351) | (0.322) | (0.311) | |

| Cellphone (Ref = without cellphone) | 1.335 | 1.179 | 1.058 | 0.915 | 1.965 *** |

| (0.291) | (0.161) | (0.147) | (0.121) | (0.468) | |

| Improved Water (Ref = unimproved water) | 0.496 * | 1.223 | 1.432 * | 1.138 | 0.571 * |

| (0.210) | (0.257) | (0.299) | (0.242) | (0.183) | |

| Constant | 1.037 | 1.733 | 0.380 | 0.298 * | 0.191 |

| (1.023) | (1.372) | (0.263) | (0.201) | (0.260) | |

| Observations | 1740 | 1576 | 1749 | 1749 | 1749 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas-Gaibor, K.; Rendón-Viteri, K.; Alvarado-Villa, G.; Faytong-Haro, M. Influences of Maternal, Child, and Household Factors on Diarrhea Management in Ecuador. Children 2025, 12, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040473

Vargas-Gaibor K, Rendón-Viteri K, Alvarado-Villa G, Faytong-Haro M. Influences of Maternal, Child, and Household Factors on Diarrhea Management in Ecuador. Children. 2025; 12(4):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040473

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas-Gaibor, Karla, Kevin Rendón-Viteri, Geovanny Alvarado-Villa, and Marco Faytong-Haro. 2025. "Influences of Maternal, Child, and Household Factors on Diarrhea Management in Ecuador" Children 12, no. 4: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040473

APA StyleVargas-Gaibor, K., Rendón-Viteri, K., Alvarado-Villa, G., & Faytong-Haro, M. (2025). Influences of Maternal, Child, and Household Factors on Diarrhea Management in Ecuador. Children, 12(4), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040473