Early Struggles—The Relationship of Psychopathology and Development in Early Childhood

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Design

1.2. Participants

1.2.1. Study Procedures

1.2.2. Early Psychopathology

1.2.3. Developmental Status

1.3. Statistical Analyses

2. Results

2.1. Participants

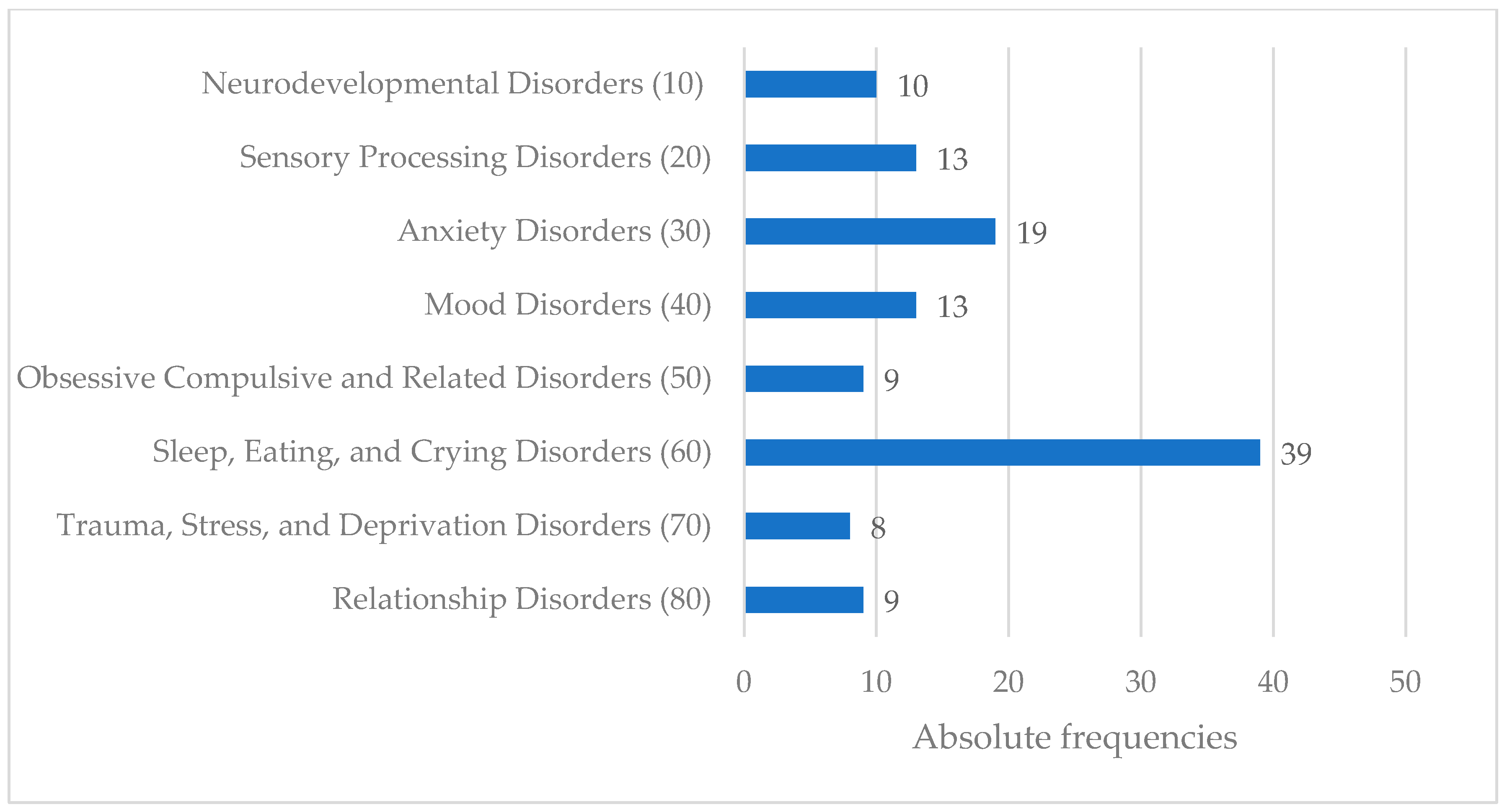

2.2. Early Psychopathology

2.3. Child Development

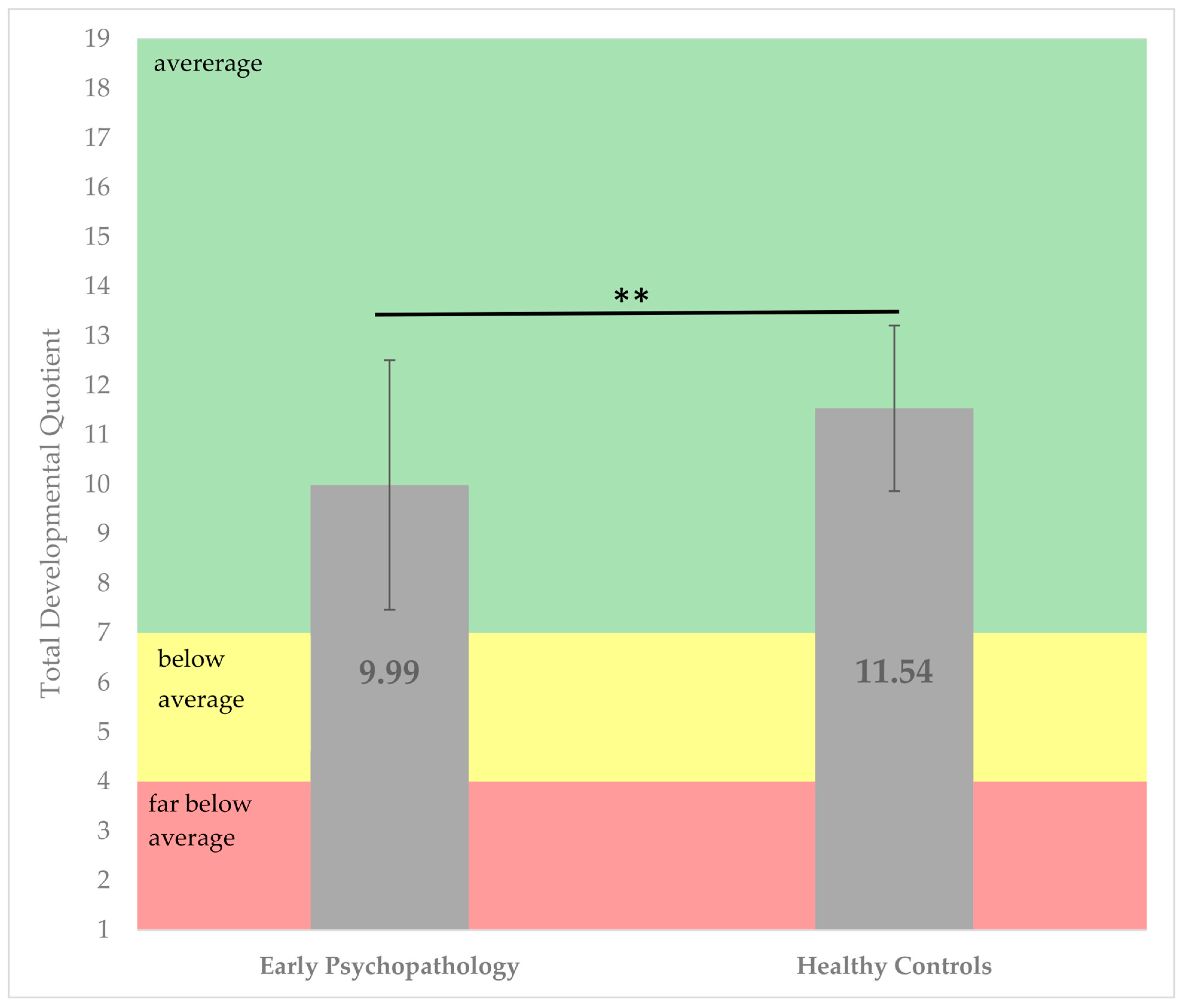

2.3.1. Total Development Quotient

2.3.2. Developmental Domains

2.3.3. Analysis of Confounding Factors

2.3.4. Influence of Confounding Factors

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steffen, A.; Akmatov, M.K.; Holstiege, J.; Bätzing, J. Diagnoseprävalenz Psychischer Störungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Eine Analyse Bundesweiter Vertragsärztlicher Abrechnungsdaten der Jahre 2009 bis 2017. Available online: https://www.versorgungsatlas.de/fileadmin/ziva_docs/93/VA_18-07_Bericht_PsychStoerungenKinderJugendl_V2_2019-01-15.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Skovgaard, A.M.; Houmann, T.; Christiansen, E.; Landorph, S.; Jørgensen, T.; Olsen, E.M.; Heering, K.; Kaas-Nielsen, S.; Samberg, V.; Lichtenberg, A. The prevalence of mental health problems in children 1(1/2) years of age—The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard, A.M. Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. An epidemiological study. Dan. Med. Bull. 2010, 57, B4193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bolten, M.; Möhler, E.; von Gontard, A. Psychische Störungen im Säuglings- und Kleinkindalter: Exzessives Schreien, Schlaf- und Fütterstörungen; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783801723736. [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, M.A.; Cobb, J.C.; Jackson, E.B.; Harris, G.S.; Detwiler, A.C. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called “colic”. Pediatrics 1954, 14, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kries, R.; Kalies, H.; Papousek, M. Excessive crying beyond 3 months may herald other features of multiple regulatory problems. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijneveld, S.A.; Brugman, E.; Hirasing, R.A. Excessive infant crying: The impact of varying definitions. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Fischer, C.; Eickhorst, A.; Cierpka, M. Influence of early regulatory problems in infants on their development at 12 months: A longitudinal study in a high-risk sample. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffol, E.; Rantalainen, V.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Girchenko, P.; Lahti, J.; Tuovinen, S.; Lipsanen, J.; Villa, P.M.; Laivuori, H.; Hämäläinen, E.; et al. Infant regulatory behavior problems during first month of life and neurobehavioral outcomes in early childhood. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, D.; Squires, J. Ages & Stages Questionnaires; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.M.; Schlesier-Michel, A.; Otto, Y.; White, L.O.; Andreas, A.; Sierau, S.; Bergmann, S.; Perren, S.; von Klitzing, K. Latent trajectories of internalizing symptoms from preschool to school age: A multi-informant study in a high-risk sample. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Newman, D.L.; Silva, P.A. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cierpka, M. (Ed.) Frühe Kindheit 0-3: Beratung und Psychotherapie für Eltern mit Säuglingen und Kleinkindern, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 9783642202957. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, J.; Petzoldt, J.; Knappe, S.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Asselmann, E.; Wittchen, H.-U. Infant, maternal, and familial predictors and correlates of regulatory problems in early infancy: The differential role of infant temperament and maternal anxiety and depression. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 115, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, G.; Schreier, A.; Meyer, R.; Wolke, D. Predictors of crying, feeding and sleeping problems: A prospective study. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 37, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlander, T.F.; Weinberg, J.; Papsdorf, M.; Grunau, R.; Misri, S.; Devlin, A.M. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics 2008, 3, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnar, M.R.; van Dulmen, M.H.M. Behavior problems in postinstitutionalized internationally adopted children. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M.H.; Andersen, S.L.; Polcari, A.; Anderson, C.M.; Navalta, C.P.; Kim, D.M. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003, 27, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remschmidt, H.; Schmidt, M.H.; Poustka, F. (Eds.) Multiaxiales Klassifikationsschema für Psychische Störungen des Kindes- und Jugendalters Nach ICD-10: Mit Einem Synoptischen Vergleich von ICD-10 mit DSM-5; 2.Nachdruck der 7., aktualisierten Aufl. 2017; Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-456-85759-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sprengeler, M.K.; Mattheß, J.; Eckert, M.; Richter, K.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Vienhues, P.; Berghöfer, A.; Fricke, J.; Roll, S.; et al. Efficacy of parent-infant psychotherapy compared to care as usual in children with regulatory disorders in clinical and outpatient settings: Study protocol of a randomised controlled trial as part of the SKKIPPI project. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, J.; Bolster, M.; Ludwig-Körner, C.; Kuchinke, L.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; Vienhues, P.; Reinhold, T.; Berghöfer, A.; Roll, S.; Keil, T. Occurrence and determinants of parental psychosocial stress and mental health disorders in parents and their children in early childhood: Rationale, objectives, and design of the population-based SKKIPPI cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattheß, J.; Eckert, M.; Richter, K.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Vienhues, P.; Berghöfer, A.; Roll, S.; Keil, T.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; et al. Efficacy of Parent-Infant-Psychotherapy with mothers with postpartum mental disorder: Study protocol of the randomized controlled trial as part of the SKKIPPI project. Trials 2020, 21, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zero to Three. DC:0-5TM: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood; Zero to Three: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 1938558707. [Google Scholar]

- Macha, T.; Petermann, F. The ET 6–6. Z. Psychol./J. Psychol. 2008, 216, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeris, M.-G.; Hagemann, E.; Theil, M.K.; Martin, A.; Schlensog-Schuster, F. Strukturiertes ElternInterview zur Erfassung der klinischen Diagnose 0-5 Jahre (SEID 0-5). University Hospital of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2025; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Macha, T.; Petermann, F. Fallbuch ET 6-6-R: Der Entwicklungstest für Kinder von sechs Monaten bis sechs Jahren in der Praxis, 1. Auflage; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2016; ISBN 9783801725549. [Google Scholar]

- von Gontard, A. Psychische Störungen bei Säuglingen, Klein- und Vorschulkindern. In Pädiatrie; Hoffmann, G.F., Lentze, M.J., Spranger, J., Zepp, F., Berner, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 2721–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissmann, I.; Domsch, H.; Lohaus, A. Zur Stabilität und Validität von Entwicklungstestergebnissen im Alter von sechs Monaten bis zwei Jahren. Kindh. Entwickl. 2006, 15, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macha, T.; Petermann, F. Objektivität von Entwicklungstests. Diagnostica 2013, 59, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. SPSS, version 29; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, A.L.; Ammitzbøll, J.; Olsen, E.M.; Skovgaard, A.M. Problems of feeding, sleeping and excessive crying in infancy: A general population study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGangi, G.A.; Porges, S.W.; Sickel, R.Z.; Greenspan, S.I. Four-year follow-up of a sample of regulatory disordered infants. Infant Ment. Health J. 1993, 14, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikam, R.; Perman, J.A. Pediatric feeding disorders. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2000, 30, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, S.W.; Skovgaard, A.M.; Ammitzbøll, J.; Holstein, B.E.; Pedersen, T.P. Motor development problems in infancy predict mental disorders in childhood: A longitudinal cohort study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 2655–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard, A.M.; Olsen, E.M.; Christiansen, E.; Houmann, T.; Landorph, S.L.; Jørgensen, T. Predictors (0–10 months) of psychopathology at age 11/2 years—A general population study in The Copenhagen Child Cohort CCC 2000. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGangi, G.A.; Breinbauer, C.; Roosevelt, J.D.; Porges, S.; Greenspan, S. Prediction of childhood problems at three years in children experiencing disorders of regulation during infancy. Infant Ment. Health J. 2000, 21, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, D.; Schmid, G.; Schreier, A.; Meyer, R. Crying and feeding problems in infancy and cognitive outcome in preschool children born at risk: A prospective population study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piek, J.P.; Barrett, N.C.; Smith, L.M.; Rigoli, D.; Gasson, N. Do motor skills in infancy and early childhood predict anxious and depressive symptomatology at school age? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2010, 29, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdsson, E.; van Os, J.; Fombonne, E. Childhood motor impairment and persistent anxiety in adolescent boys. Eur. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, K.A.; Wedderburn, C.J.; Barnett, W.; Nhapi, R.T.; Rehman, A.M.; Stadler, J.A.M.; Hoffman, N.; Koen, N.; Zar, H.J.; Stein, D.J. Risk and protective factors for child development: An observational South African birth cohort. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 90, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmussen, J.; Davidsen, K.A.; Olsen, A.L.; Skovgaard, A.M.; Bilenberg, N. The longitudinal association of combined regulatory problems in infancy and mental health outcome in early childhood: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 3679–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, F.; Giallo, R.; Hiscock, H.; Mensah, F.; Sanchez, K.; Reilly, S. Infant Regulation and Child Mental Health Concerns: A Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20180977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsch, F.; Petermann, U.; Schmidt, S.; Petermann, F. Kognitive, sprachliche, motorische und sozial-emotionale Defizite bei verhaltensauffälligen Schulanfängern. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2013, 62, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, B.; Carlson, E.; Sroufe, L.A. Resilience as process. Dev. Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample (N = 83) | Early Psychopathology (n = 43) | Healthy Controls (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Age in month (M, SD) | 29.0 (16.9) | 29.9 (18.1) | 28.1 (15.7) |

| Sex (n, %) | |||

| Male | 41 (49.4) | 23 (53.5) | 18 (45.0) |

| Birthweight in grams (M, SD) | 3345.11 (577.8) | 3314.6 (582.0) | 3377.9 (577.7) |

| Gestational age in weeks (M, SD) | 39.4 (2.4) | 39.33 (2.1) | 39.40 (2.6) |

| Number of siblings (n, %) | |||

| No siblings | 35 (42.7) | 20 (47.6) | 15 (37.5) |

| One sibling | 39 (47.6) | 16 (38.1) | 23 (57.5) |

| ≥2 siblings | 8 (9.8) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (5.0) |

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Age in years (M, SD) | 34.46 (4.4) | 34.53 (4.6) | 34.81 (4.2) |

| Origin (n, %) | |||

| German | 82 (98.8) | 42 (97.7) | 40 (100.0) |

| Education (median) | University degree | High school diploma | University degree |

| Partnered (n, %) | 73 (90.1) | 34 (81.0) | 39 (97.5) |

| Custody of child (n, %) | |||

| Shared | 68 (84.0) | 30 (73.2) | 38 (95.0) |

| Mother alone | 13 (16.0) | 11 (26.8) | 2 (5.0) |

| Monthly household income (median) | >3.500€ | >3000€–<3500€ | >3.500€ |

| Developmental Quotient (DQ) | EPP | HC | t (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross motor skills (M, SD) | 10.3 (3.9) | 11.4 (2.9) | 1.4 (80) | 0.078 |

| Fine motor skills (M, SD) | 10.2 (3.0) | 11.4 (2.4) | 2.0 (80) | 0.023 * |

| Cognition (M, SD) | 10.2 (3.6) | 11.7 (3.3) | 1.9 (80) | 0.031 * |

| Language development (M, SD) | 10.3 (2.9) | 11.6 (1.8) | 2.5 (80) | 0.007 ** |

| Developmental Quotient (DQ) | Corrected R² | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross motor skill | 0.001 | 0.206 | 0.285 |

| Fine motor skill | 0.026 | 0.081 | 0.396 |

| Cognition | 0.019 | 0.072 | 0.408 |

| Language development | 0.070 | 0.056 | 0.434 |

| Socioemotional | 0.168 | ≤0.001 | 0.943 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martin, A.; Galeris, M.-G.; Theil, M.K.; Sele, S.; Cavelti, M.; Keil, J.; Kaess, M.; von Polier, G.G.; Schlensog-Schuster, F. Early Struggles—The Relationship of Psychopathology and Development in Early Childhood. Children 2025, 12, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030265

Martin A, Galeris M-G, Theil MK, Sele S, Cavelti M, Keil J, Kaess M, von Polier GG, Schlensog-Schuster F. Early Struggles—The Relationship of Psychopathology and Development in Early Childhood. Children. 2025; 12(3):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartin, Annick, Mirijam-Griseldis Galeris, Mona K. Theil, Silvano Sele, Marialuisa Cavelti, Jan Keil, Michael Kaess, Georg G. von Polier, and Franziska Schlensog-Schuster. 2025. "Early Struggles—The Relationship of Psychopathology and Development in Early Childhood" Children 12, no. 3: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030265

APA StyleMartin, A., Galeris, M.-G., Theil, M. K., Sele, S., Cavelti, M., Keil, J., Kaess, M., von Polier, G. G., & Schlensog-Schuster, F. (2025). Early Struggles—The Relationship of Psychopathology and Development in Early Childhood. Children, 12(3), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030265