The Interlinkages Between Ambient Temperature and Air Pollution in Exacerbating Childhood Asthma: A Time Series Study in Cape Town, South Africa †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Childhood Asthma Data

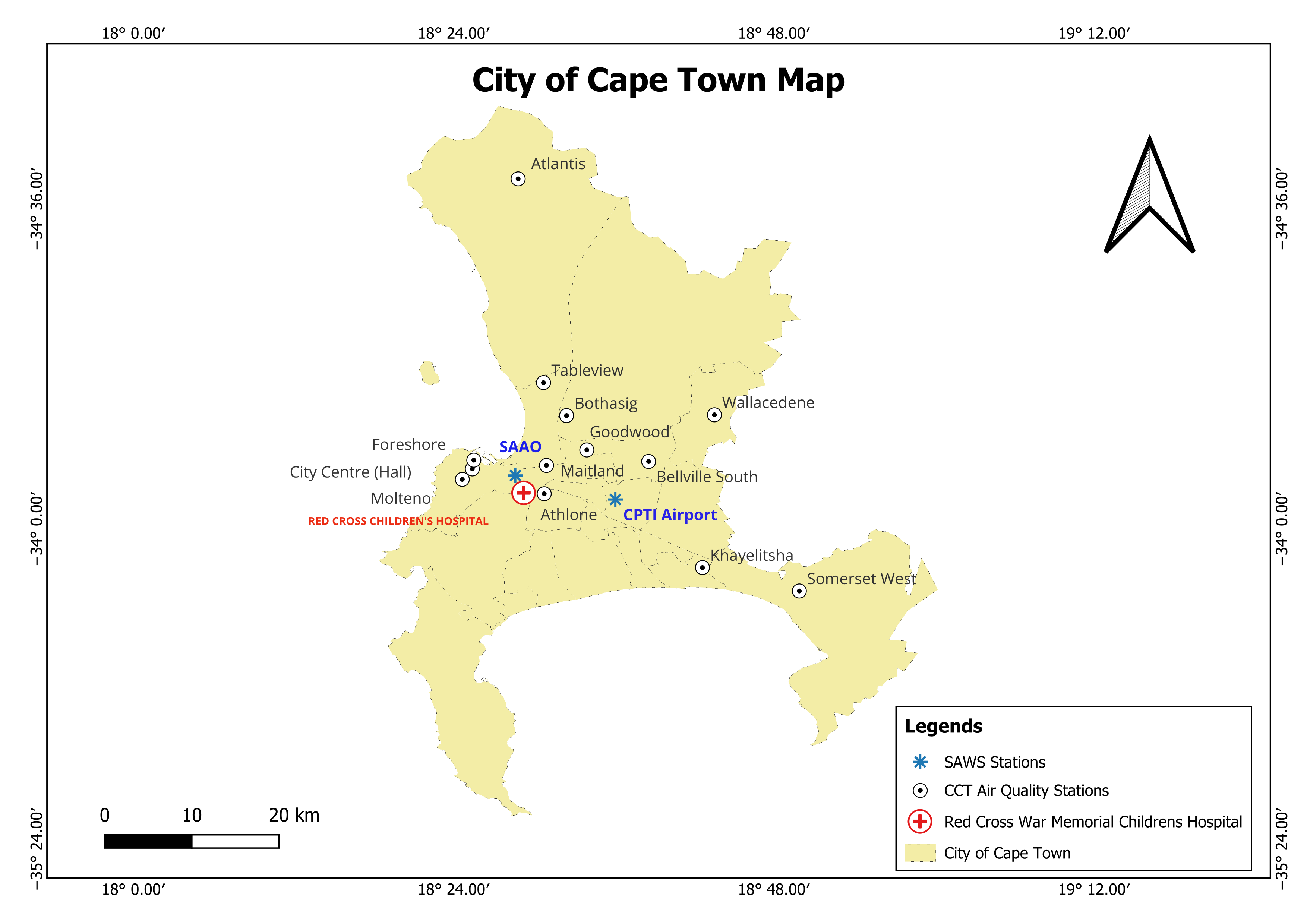

2.3. Air Quality and Temperature Data

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Health Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Temperature Variables and Air Pollutants

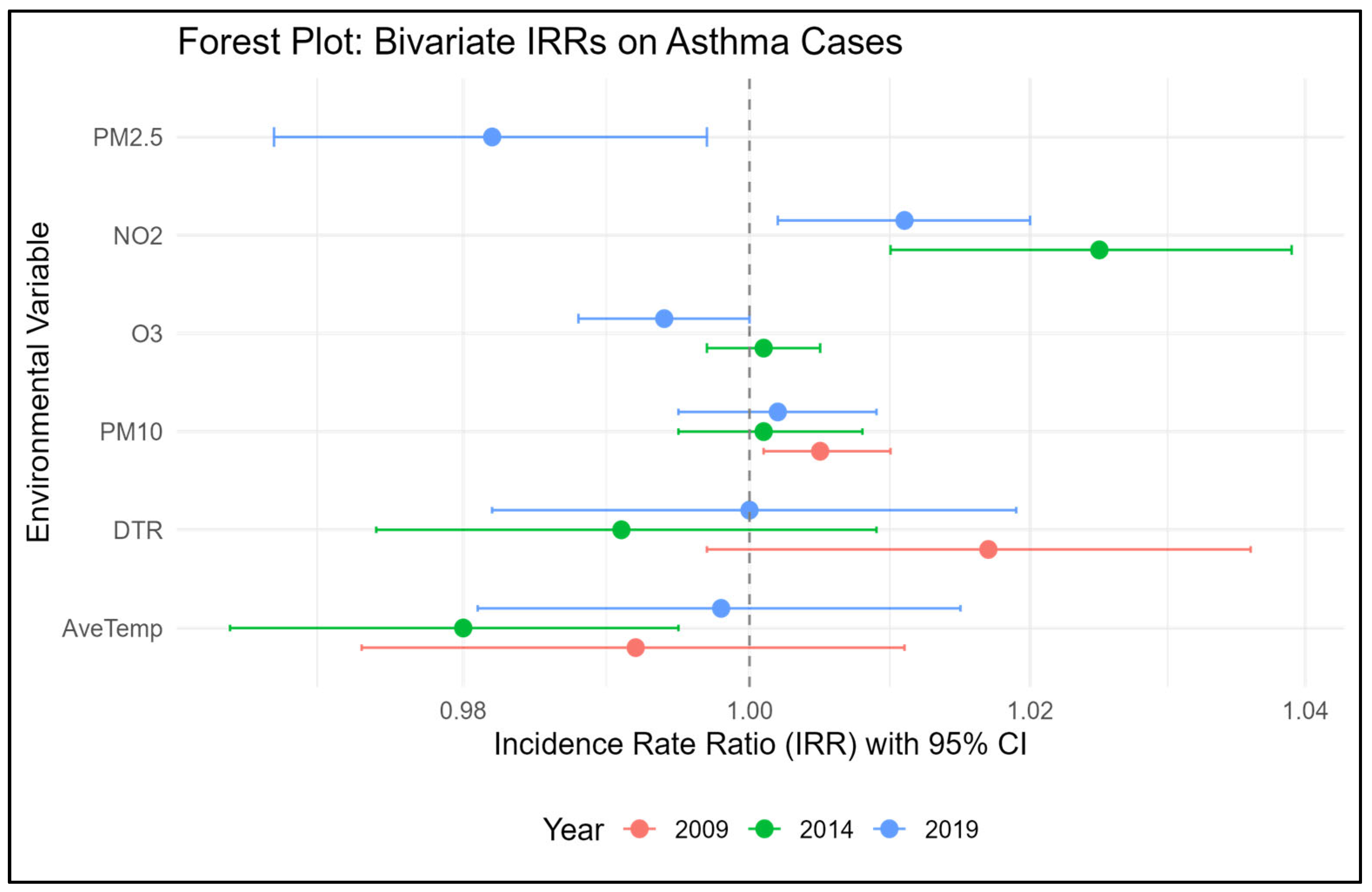

3.3. Association Between Childhood Asthma, Air Pollution, and Temperature Variables

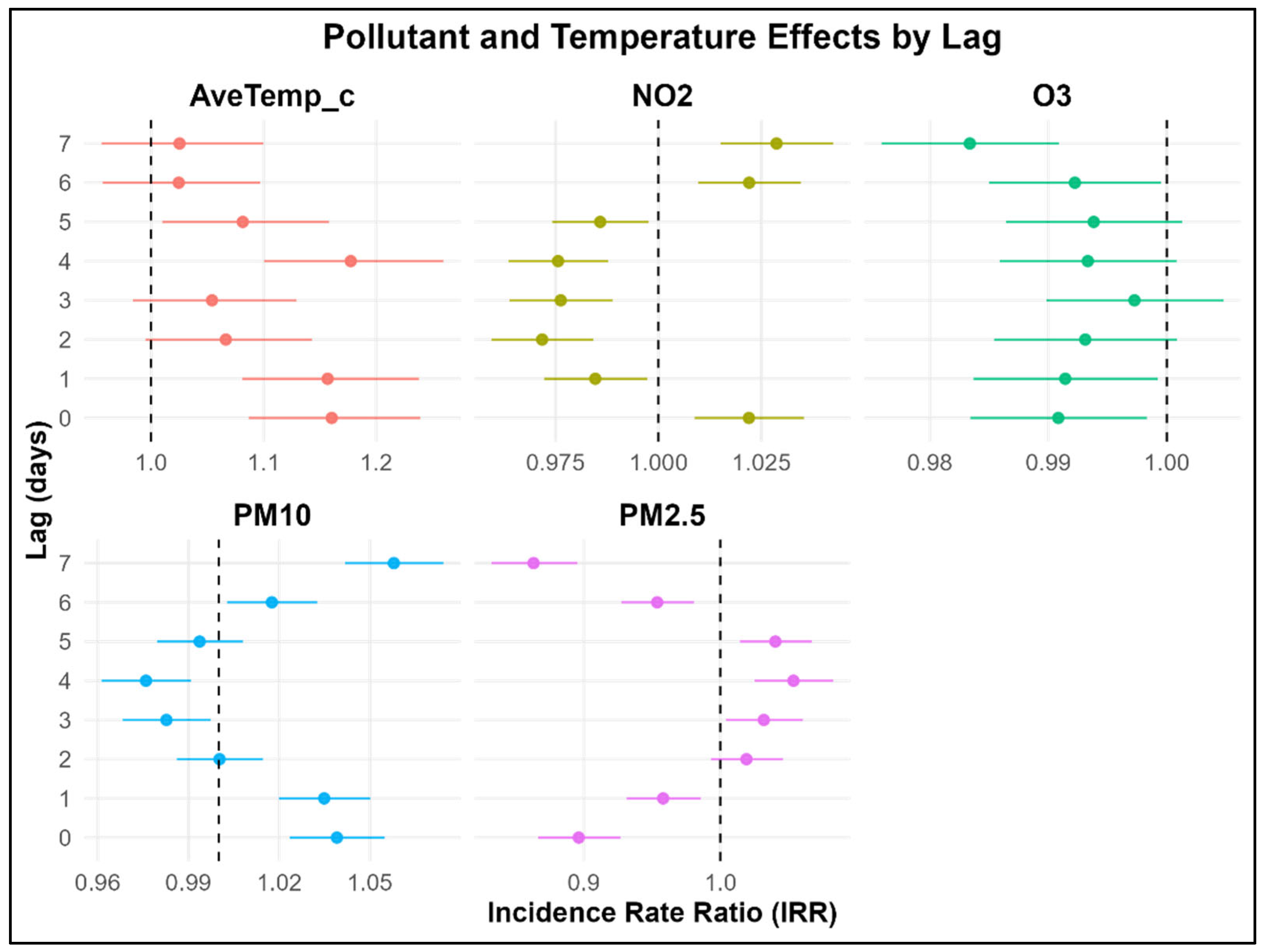

3.4. Multivariable Delayed Association Between Childhood Asthma, Air Pollution, and Temperature Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DLNM | Distributed Lag Non-Linear Model |

| DTR | Diurnal Temperature Ranges |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| CCT | City of Cape Town |

| GHGs | Greenhouse Gases |

| ICD-10 Code | International Classification of Diseases Codes |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRR | Incidence Rate Ratio |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| NAAQS | South African National Ambient Air Quality Standards |

| NO2 μg/m3 | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| O3 μg/m3 | Ozone |

| PM10 μg/m3 | Particulate Matter with a diameter smaller than 10 micrograms |

| PM2.5 μg/m3 | Particulate Matter 2.5 |

| RXH | Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital |

| SANAS | South African National Accreditation System |

| SD | Standard Deviations |

References

- Helldén, D.; Andersson, C.; Nilsson, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Friberg, P.; Alfvén, T. Climate Change and Child Health: A Scoping Review and an Expanded Conceptual Framework. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e164–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annan, H.; Baran, I.; Litwin, S. Five I’s of Climate Change and Child Health: A Framework for Pediatric Planetary Health Education. Pediatrics 2024, 154, e2024066064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achakulwisut, P.; Brauer, M.; Hystad, P.; Anenberg, S.C. Global, National, and Urban Burdens of Paediatric Asthma Incidence Attributable to Ambient NO2 Pollution: Estimates from Global Datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e166–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleb, A.; Abeje, E.T.; Daba, C.; Endawkie, A.; Tsega, Y.; Abere, G.; Mamaye, Y.; Bezie, A.E. The Odds of Developing Asthma and Wheeze among Children and Adolescents Exposed to Particulate Matter: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.C.; Kattan, M.; O’Connor, G.T.; Murphy, R.C.; Whalen, E.; LeBeau, P.; Calatroni, A.; Gill, M.A.; Gruchalla, R.S.; Liu, A.H.; et al. Associations between Outdoor Air Pollutants and Non-Viral Asthma Exacerbations and Airway Inflammatory Responses in Children and Adolescents Living in Urban Areas in the USA: A Retrospective Secondary Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e33–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, R.E.M.; Masekela, R. A Historical Overview of Childhood Asthma in Southern Africa: Are We There Yet? Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 27, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martínez, M.E.; Soto-Quiros, M.E.; Custovic, A. Childhood Asthma: Low and Middle-Income Countries Perspective. Acta Medica Acad. 2020, 49, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Souëf, P.N.; Adachi, Y.; Anastasiou, E.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Badellino, H.A.; Banzon, T.; Beltrán, C.P.; D’Amato, G.; El-Sayed, Z.A.; Gómez, R.M.; et al. Global Change, Climate Change, and Asthma in Children: Direct and Indirect Effects—A WAO Pediatric Asthma Committee Report. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrufardi, F.; Manullang, A.; Rusmawatiningtyas, D.; Chung, K.F.; Lin, S.C.; Chuang, H.C. Extreme Weather and Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, C.M.; Peter, J. Climate Change and Its Impact on Asthma in South Africa. Curr. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 38, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyan, T.; Dalvie, M.A.; Röösli, M.; Naidoo, R.; Künzli, N.; de Hoogh, K.; Parker, B.; Leaner, J.; Jeebhay, M. Asthma-related Outcomes Associated with Indoor Air Pollutants among Schoolchildren from Four Informal Settlements in Two Municipalities in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo-Ojo, T.C.; Wichmann, J.; Arowosegbe, O.O.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Schindler, C.; Künzli, N. Short-Term Effects of PM10, NO2, SO2 and O3 on Cardio-Respiratory Mortality in Cape Town, South Africa, 2006–2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabethe, N.D.L.; Voyi, K.; Wichmann, J. Association between Ambient Air Pollution and Cause-Specific Mortality in Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg, South Africa: Any Susceptible Groups? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 42868–42876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichmann, J.; Voyi, K. Ambient Air Pollution Exposure and Respiratory, Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Mortality in Cape Town, South Africa: 2001–2006. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3978–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokotola, C.L.; Wright, C.Y.; Wichmann, J. Temperature as a Modifier of the Effects of Air Pollution on Cardiovascular Disease Hospital Admissions in Cape Town, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 16677–16685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, T.; Jeebhay, M.; Röösli, M.; Naidoo, R.N.; Künzli, N.; de Hoogh, K.; Saucy, A.; Badpa, M.; Baatjies, R.; Parker, B. The Association between Ambient NO2 and PM2.5 with the Respiratory Health of School Children Residing in Informal Settlements: A Prospective Cohort Study. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.I.; Rutter, C.E.; Bissell, K.; Chiang, C.Y.; El Sony, A.; Ellwood, E.; Ellwood, P.; García-Marcos, L.; Marks, G.B.; Morales, E.; et al. Worldwide Trends in the Burden of Asthma Symptoms in School-Aged Children: Global Asthma Network Phase I Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettifor, J.M. The New Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital—A White Elephant or an Essential Development for Paediatric Care in Johannesburg? S. Afr. J. Child Health 2017, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiker, Y.; Diab, R.D.; Zunckel, M.; Hayes, E.T. Introduction of Local Air Quality Management in South Africa: Overview and Challenges. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 17, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg-Enslin, H. Air Quality Evolution in South Africa over the Past 20 Years: A Journey from a Consultant’s Viewpoint. Clean Air J. 2024, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Petrik, L.; Wichmann, J. PM2.5 Chemical Composition and Geographical Origin of Air Masses in Cape Town, South Africa. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, A.; Naidoo, D. State of Environment Outlook Report for the Western Cape Province: Air Quality; Western Cape Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khumalo, T.N. 2019 State of the Air Report and National Air Quality Indicator. 2020. Available online: https://saaqis.environment.gov.za/Pagesfiles/State%20of%20Air%20Report%20-%202020.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Alfeus, A.; Molnar, P.; Boman, J.; Shirinde, J.; Wichmann, J. Inhalation Health Risk Assessment of Ambient PM2.5 and Associated Trace Elements in Cape Town, South Africa. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2022, 28, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Air Pollution and Child Health: Prescribing Clean Air: Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. The Environment National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act, 2004 (Act No. 39 of 2004); Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment: Cape Town, South Africa, 2009.

- Morakinyo, O.M.; Mukhola, M.S.; Mokgobu, M.I. Ambient Gaseous Pollutants in an Urban Area in South Africa: Levels and Potential Human Health Risk. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinde, J.; and Wichmann, J. Temperature Modifies the Association between Air Pollution and Respiratory Disease Mortality in Cape Town, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2023, 33, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Zhou, X.; Guo, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Huang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. Associations between Air Pollutant and Pneumonia and Asthma Requiring Hospitalization among Children Aged under 5 Years in Ningbo, 2015–2017. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1017105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olutola, B.G.; Mwase, N.S.; Shirinde, J.; Wichmann, J. Apparent Temperature Modifies the Effects of Air Pollution on Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Cape Town, South Africa. Climate 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, F.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Geng, F.; Xu, J.; Zhen, C.; Shen, X.; Tong, S. The Association between Cold Spells and Pediatric Outpatient Visits for Asthma in Shanghai, China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, C.; Su, H.; Turner, L.R.; Qiao, Z.; Tong, S. Diurnal Temperature Range and Childhood Asthma: A Time-Series Study. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Gasparrini, A.; Hajat, S.; Smeeth, L.; Armstrong, B. Time Series Regression Studies in Environmental Epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, A.J.; Peden, D.B. Assessing the Impact of Air Pollution on Childhood Asthma Morbidity: How, When and What to Do. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 18, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, S.; Fan, C.; Bai, Z.; Yang, K. The Impact of PM2.5 on Asthma Emergency Department Visits: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulos, N.; Pantazopoulos, I.; Mermiri, M.; Mavrovounis, G.; Kalantzis, G.; Saharidis, G.; Gourgoulianis, K. Effect of PM2.5 Levels on Respiratory Pediatric ED Visits in a Semi-Urban Greek Peninsula. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lim, Y.; Kim, H. Outdoor Temperature Changes and Emergency Department Visits for Asthma in Seoul, Korea: A Time-Series Study. Environ. Res. 2014, 135, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Batterman, S.; Wasilevich, E.; Wahl, R.; Wirth, J.; Su, F.C.; Mukherjee, B. Association of Daily Asthma Emergency Department Visits and Hospital Admissions with Ambient Air Pollutants among the Pediatric Medicaid Population in Detroit: Time-Series and Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Analyses with Threshold Effects. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Crooks, J.L.; Davies, J.M.; Khan, A.F.; Hu, W.; Tong, S. The Association between Ambient Temperature and Childhood Asthma: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.B.; Sarria, E.E.; Camargos, P.; Mocelin, H.T.; Soto-Quiroz, M.; Cruz, A.A.; Bousquet, J.; Zar, H.J. Childhood Asthma in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Where Are We Now? Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2019, 31, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.A.; Card, J.W.; Voltz, J.W.; Arbes Jr, S.J.; Germolec, D.R.; Korach, K.S.; Zeldin, D.C. It’s All about Sex: Male-Female Differences in Lung Development and Disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2007, 18, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.U.; Guntur, V.P.; Newcomb, D.C.; Wechsler, M.E. Sex and Gender in Asthma. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 210067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.; Silveyra, P. Sex Differences in Paediatric and Adult Asthma. Eur. Med. J. Chelmsf. Engl. 2019, 4, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuseini, H.; Newcomb, D.C. Mechanisms Driving Gender Differences in Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denlinger, L.C.; Heymann, P.; Lutter, R.; Gern, J.E. Exacerbation-prone asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2020, 8, 474-482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco, M.E.; Ferrante, G.; Amato, D.; Capizzi, A.; De Pieri, C.; Ferraro, V.A.; Furno, M.; Tranchino, V.; La Grutta, S. Climate Change and Childhood Respiratory Health: A Call to Action for Paediatricians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, J.A.; McLaughlin, A.P.; Stenger, P.J.; Patrie, J.; Brown, M.A.; El-Dahr, J.M.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; Byrd, N.J.; Heymann, P.W. A Comparison of Seasonal Trends in Asthma Exacerbations among Children from Geographic Regions with Different Climates; OceanSide Publications: Providence, RI, USA, 2016; Volume 37, p. 475. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, D. Pollen Monitoring in South Africa: Review Article. Curr. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 20, 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, D.M. Variations in Pollen and Fungal Spore Air Spora: An Analysis of 30 Years of Monitoring for the Clinical Assessment of Patients in the Western Cape; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Motlogeloa, O.; Fitchett, J.M.; Sweijd, N. Defining the South African Acute Respiratory Infectious Disease Season. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.S.A.; Morrow, B.M.; Hardie, D.R.; Argent, A.C. An Investigation into the Prevalence and Outcome of Patients Admitted to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit with Viral Respiratory Tract Infections in Cape Town, South Africa. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 13, e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.Y.; Lee, Y.L.; Guo, Y.L. Indoor Environmental Risk Factors and Seasonal Variation of Childhood Asthma. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 20, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bont, J.; Rajiva, A.; Mandal, S.; Stafoggia, M.; Banerjee, T.; Dholakia, H.; Garg, A.; Ingole, V.; Jaganathan, S.; Kloog, I.; et al. Synergistic Associations of Ambient Air Pollution and Heat on Daily Mortality in India. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areal, A.T.; Zhao, Q.; Wigmann, C.; Schneider, A.; Schikowski, T. The Effect of Air Pollution When Modified by Temperature on Respiratory Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Qian, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. Interaction Effect of Prenatal and Postnatal Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Temperature on Childhood Asthma. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndletyana, O.; Madonsela, B.S. Spatial Distribution of PM10 and NO2 in Ambient Air Quality in Cape Town CBD, South Africa. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2023, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte-Moreno, O.; González-Barcala, F.J.; Muñoz-Gall, X.; Pueyo-Bastida, A.; Ramos-González, J.; Urrutia-Landa, I. Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma: A Scoping Review. Open Respir. Arch. 2023, 5, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ding, H.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Guan, W. Association between Air Pollutants and Asthma Emergency Room Visits and Hospital Admissions in Time Series Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amialchuk, A.; Sapci, O. The Effect of Long-Term Exposure to O3 and PM2.5 on Allergies and Asthma in Adolescents and Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2025, 22, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wu, J.; Lin, X. Ozone Exposure and Asthma Attack in Children. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 830897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, T.L.; Beukes, J.P.; Zyl, P.G. van Measurement of Surface Ozone in South Africa with Reference to Impacts on Human Health. Clean Air J. 2015, 25, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amâncio, C.T.; Nascimento, L.F.C. Asthma and Ambient Pollutants: A Time Series Study. Rev. Assoc. Medica Bras (1992). 2012, 58, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Department of Envaironmental Affairs and Planning. Air Quality Management Plan for the Western Cape Province; Western Cape Department of Envaironmental Affairs and Planning: Cape Town, South Africa, 2010. Available online: https://saaqis.environment.gov.za/documents/AQPlanning/Air%20Quality%20Management%20Plan%20for%20the%20Western%20Cape%20Province.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Wright, C.; Oosthuizen, R. Air Quality Monitoring and Evaluation Tools for Human Health Risk Reduction in South Africa; National Association for Clean Air Conference (NACA 2009): Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (Dea&Dp). Air Quality Management Plan 2016. In Generation Western Cape Air Quality Management Plan, 2nd ed.; Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.D.; Bell, M.L. Spatial Misalignment in Time Series Studies of Air Pollution and Health Data. Biostat. Oxf. Engl. 2010, 11, 720–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanker, A.; Gie, R.P.; Zar, H.J. The Association between Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure and Childhood Respiratory Disease: A Review. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2017, 11, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikamjee, T.; Comberiati, P.; Peter, J. Pediatric Asthma in Developing Countries: Challenges and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 22, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | 2009 (N = 1953) | 2014 (N = 2701) | 2019 (N = 3099) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Type of admission | 0.0822 | |||

| Inpatient | 95 (5) | 129 (5) | 185 (6) | |

| Outpatient | 1858 (95) | 2572 (95) | 2914 (94) | |

| Gender | 0.277 | |||

| Male | 1113 (57) | 1506 (56) | 1792 (58) | |

| Female | 840 (43) | 1195 (44) | 1306 (42) | |

| Age | 0.246 | |||

| Group (6–9) | 1211 (62) | 1736 (64) | 1943 (63) | |

| Group (10–13) | 742 (38) | 965 (36) | 1156 (37) | |

| Area of residence | <0.000001 | |||

| Athlone | 1020 (52) | 1352 (50) | 1998 (64.5) | |

| Khayelitsha | 607 (31) | 896 (33) | 654 (21.1) | |

| City Hall | 89 (5) | 126 (5) | 100 (3.2) | |

| Other | 237 (12) | 327 (12) | 347 (11.2) | |

| Types of asthma | <0.000001 | |||

| Predominantly Allergic asthma | 703 (36) | 1635 (61) | 1775 (57) | |

| Other Asthma | 1250 (64) | 1066 (39) | 1324 (43) | |

| Season of the year | 0.383 | |||

| Summer | 537 (27) | 707 (26) | 845 (27) | |

| Autumn | 521 (27) | 677 (25) | 774 (25) | |

| Winter | 514 (26) | 725 (27) | 847 (27) | |

| Spring | 381 (20) | 592 (22) | 633 (20) |

| Environmental Exposures (Unit) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2014 | 2019 | ||

| Average Temp (°C) | 18.0 (3.8) | 18.3 (3.9) | 18.0 (3.5) | <0.0001 * |

| DTR (°C) | 9.3 (3.7) | 9.9 (3.6) | 9.6 (3.4) | <0.0001 * |

| PM10 (µg/m3) | 36.2 (17.1) | 25.4 (10.0) | 21.1 (9.0) | <0.0001 * |

| O3 (µg/m3) | - | 20.8 (16.6) | 41.2 (11.5) | <0.0001 # |

| NO2 (µg/m3) | - | 19.6 (6.2) | 12.9 (7.4) | <0.0001 # |

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) | - | - | (4.5) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phakisi, T.K.; Weimann, E.; Rother, H.-A. The Interlinkages Between Ambient Temperature and Air Pollution in Exacerbating Childhood Asthma: A Time Series Study in Cape Town, South Africa. Children 2025, 12, 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121634

Phakisi TK, Weimann E, Rother H-A. The Interlinkages Between Ambient Temperature and Air Pollution in Exacerbating Childhood Asthma: A Time Series Study in Cape Town, South Africa. Children. 2025; 12(12):1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121634

Chicago/Turabian StylePhakisi, Tshepo Kingsley, Edda Weimann, and Hanna-Andrea Rother. 2025. "The Interlinkages Between Ambient Temperature and Air Pollution in Exacerbating Childhood Asthma: A Time Series Study in Cape Town, South Africa" Children 12, no. 12: 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121634

APA StylePhakisi, T. K., Weimann, E., & Rother, H.-A. (2025). The Interlinkages Between Ambient Temperature and Air Pollution in Exacerbating Childhood Asthma: A Time Series Study in Cape Town, South Africa. Children, 12(12), 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121634