Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of MYH9-Thrombocytopenia: Insights from a Single Centric Pediatric Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussions

4.1. Variant Breakdown

- MYH9 c.3493C>T pathogenic variantPatient: 14-year-old male, chronic thrombocytopenia for 7 years.Previous treatment: Short-course corticosteroid.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Mild thrombocytopenia (60 × 109/L) macro-thrombocytes on the peripheral blood smear. Mild bruising.Family history: Father, paternal grandfather, uncle.Disease evolution to date: 25 months; mean platelet count of 32 × 109/L (range 10–60 × 109/L). No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.Genetic aspects: Familial testing revealed that the patient’s father was also carrying the genetic variant. There are multiple entries in the ClinVar database that support the germline pathogenic classification of this genetic variant and association with phenotypical manifestations of disease featuring thrombocytopenia and deafness [15,16].

- MYH9 c.4270G>A pathogenic variant—2 patients

- Patient: 21-month-old female, refractory chronic thrombocytopenia since birth.Previous treatment: Short-course corticosteroid and immunoglobulin.Family history: Negative. After diagnosis, thrombocytopenia was identified in patient’s father.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Platelet 35 × 109/L; macro-thrombocytes on the peripheral blood smear. Minor bruising and petechia.Disease evolution to date: 8 months; mean platelet count 42 × 109/L (range 19 to 85 × 109/L). No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.

- Patient: One-year-old male, chronic thrombocytopenia since birth.Previous treatment: Short-course corticosteroid.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Platelet count 36 × 109/L, and macro-thrombocytes on the peripheral blood smear. Minor bruising and petechia.Family history: Mother, grandmother, aunt.Disease evolution to date: 36 months. No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.Genetic aspects: This variant has been previously identified in a Japanese family with 14 affected individuals from 4 generations with only thrombocytopenia being reported [17]. In a large Italian study, which included 255 patients from 121 families, the variant was identified in 13 patients from 8 families, and showed a lower risk for other congenital defects compared to other variants. This variant has also been reported in an adult patient with hypertension and proteinuria. Patient had no history of bleeding episodes or other disease manifestations, but presented thrombocytopenia in childhood [18]. No severe hemorrhagic events have been reported or other manifestations of disease in either patient.

- MYH9 c.287C>T pathogenic variantPatient: 2-month-old male with severe thrombocytopenia at 24 h after birth.Previous treatment: Multiple short-course corticosteroid, 4 courses of intravenous immunoglobulin.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Platelet count of 221 × 109/L, macro-thrombocytes on the peripheral blood smear, bruising, and diffused petechiae. We discontinued all treatment pending results of genetic testing. In evolution platelet count decreased in 2 weeks to 4 × 109/L, and associated transient neutropenia (0.5 × 109/L).Bone marrow aspirate, which revealed increased megakaryocytes, no blast cells, normal granulocyte series.Family history: Negative.Disease evolution to date: 12 months, severe thrombocytopenia with platelet count below 10 × 109/L. No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.The variant was first reported in 2002, in two families, one of which was also associated with hearing loss and nephropathy [19].

- MYH9 c.5797C>T pathogenic variantPatient: 6-year-old female, chronic mild thrombocytopenia discovered at 8 months old.Previous treatment: No.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Platelet count 62 × 109/L, and macro-thrombocytes on the peripheral blood smear. No signs of bleeding.Family history: positive, multiple relatives.Disease evolution to date: 4 years; mean platelet count 66 × 109/L (range 56–71 × 109/L). No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.

- MYH9 c3485+6C>T VUSPatient: 4-year-old female with chronic refractory thrombocytopenia from 10 months old.Previous treatment: Short-course corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Severe thrombocytopenia with no macro-thrombocytes. Bone marrow analysis was normal, with a slight increase in megakaryocyte number. Bruising and petechia.Family history: Negative.Disease evolution to date: Patients started treatment with Romiplostim, with initial good response, reaching transitory platelet counts of up to 500 × 109/L for up to 10 weeks at a time, but no stable response was achieved. Genetic testing was performed after TPO-RA loss of response.Monitorization period is 6 years, with patient maintaining platelet count <10 × 109/L.Genetic aspects: This variant has not been previously reported in the medical literature or in ClinVar database. After variant reevaluation, it was maintained as a VUS. No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.

- MYH9 c.5411A>GPatient: 21-year-old female, chronic thrombocytopenia from 10 years old.Previous treatment: Short-course corticosteroid.Clinical and laboratory findings at first admission: Platelet count of 39 × 109/L, no macro-thrombocytes described on the peripheral blood smear.Family history: Negative.Genetic aspects: The variant was predicted to be tolerated by most in silico tools utilized in genetic testing; however, patient maintains phenotypic manifestation of disease with chronic thrombocytopenia. Variant reevaluation classified it as Likely Pathogenic based on PM1, PM2, PM6, and PP2 criteria. The variant has not been previously reported in the medical literature or in the ClinVar database. No life-threatening hemorrhagic events, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1. No extra-hematological involvement.

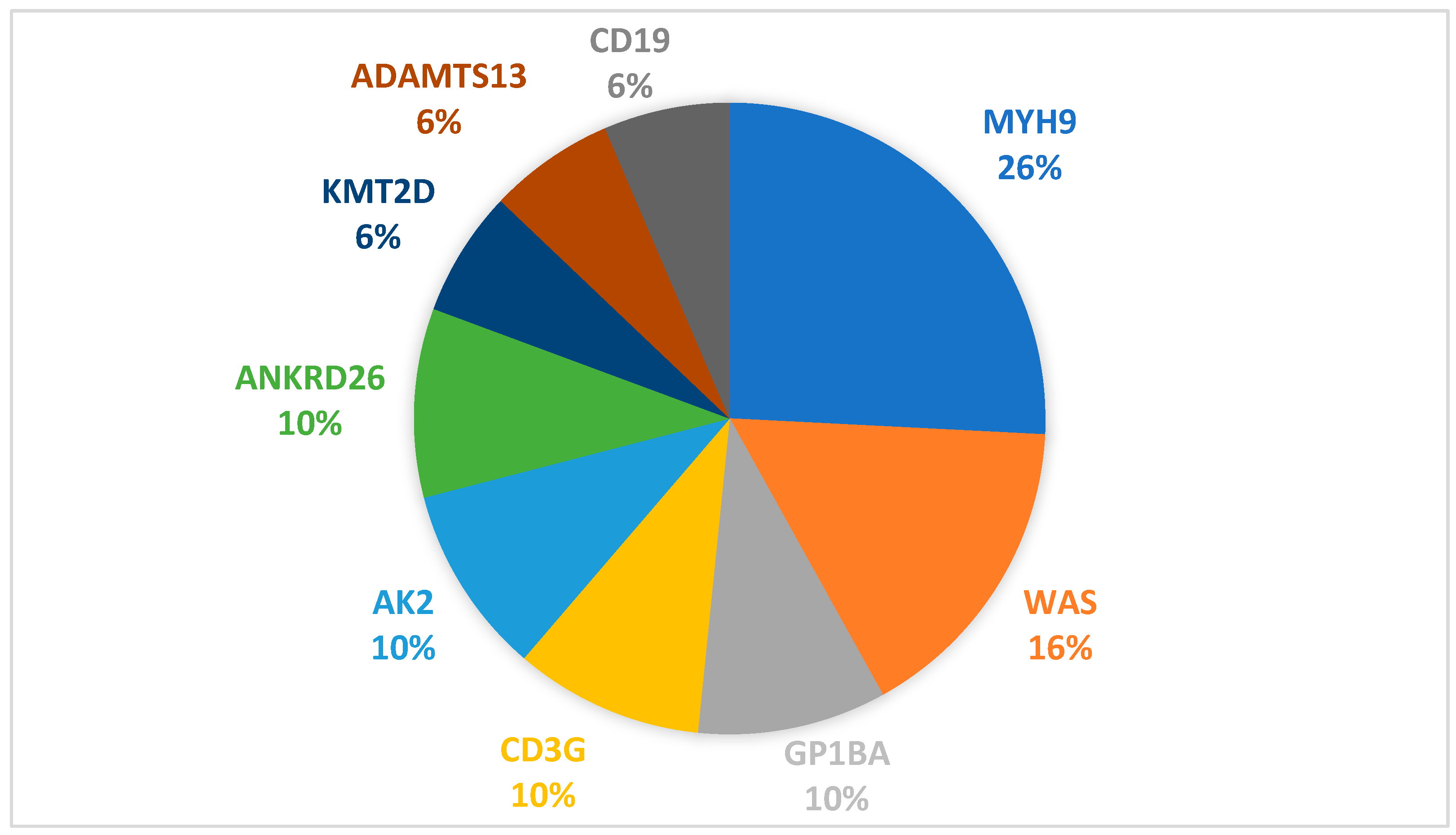

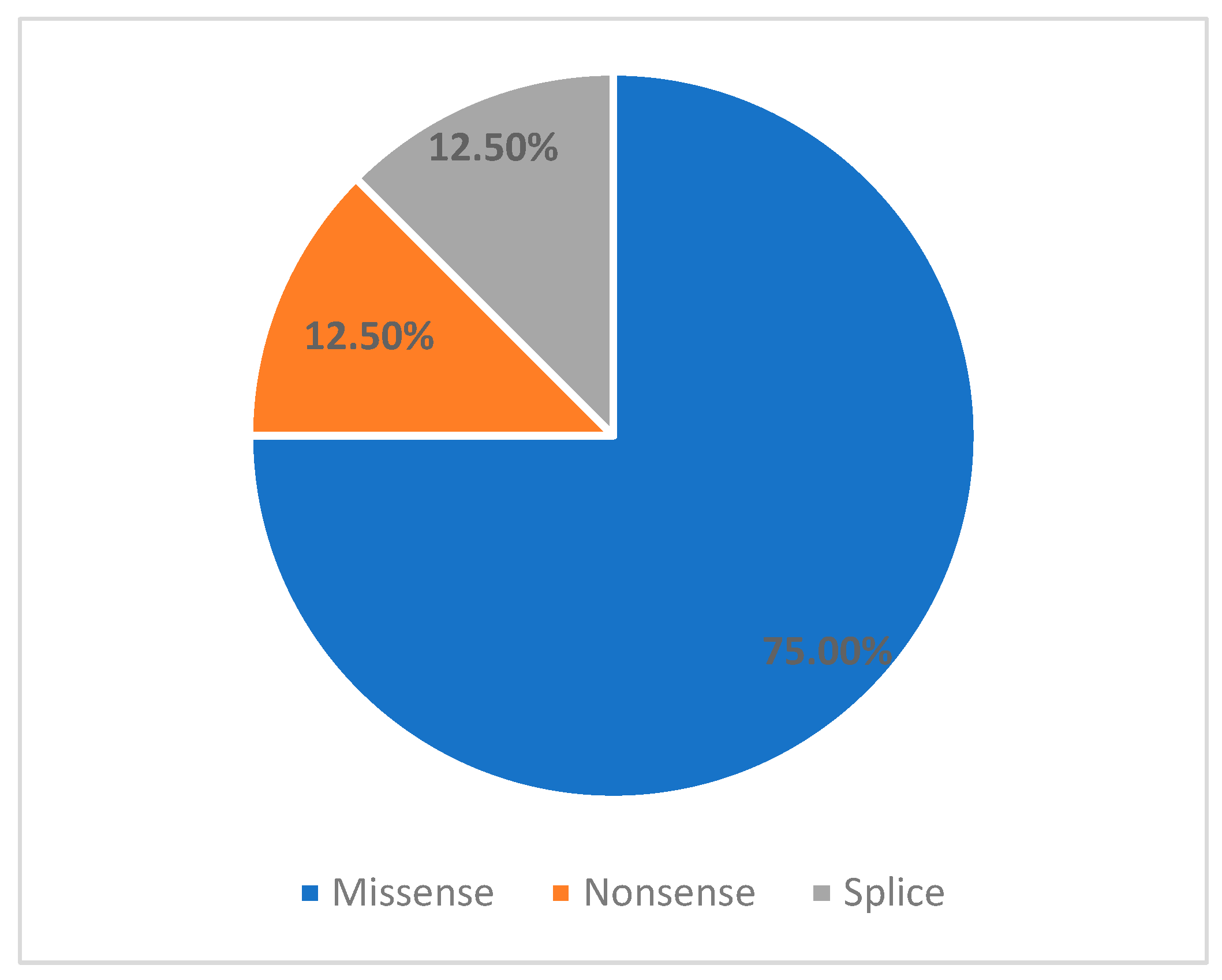

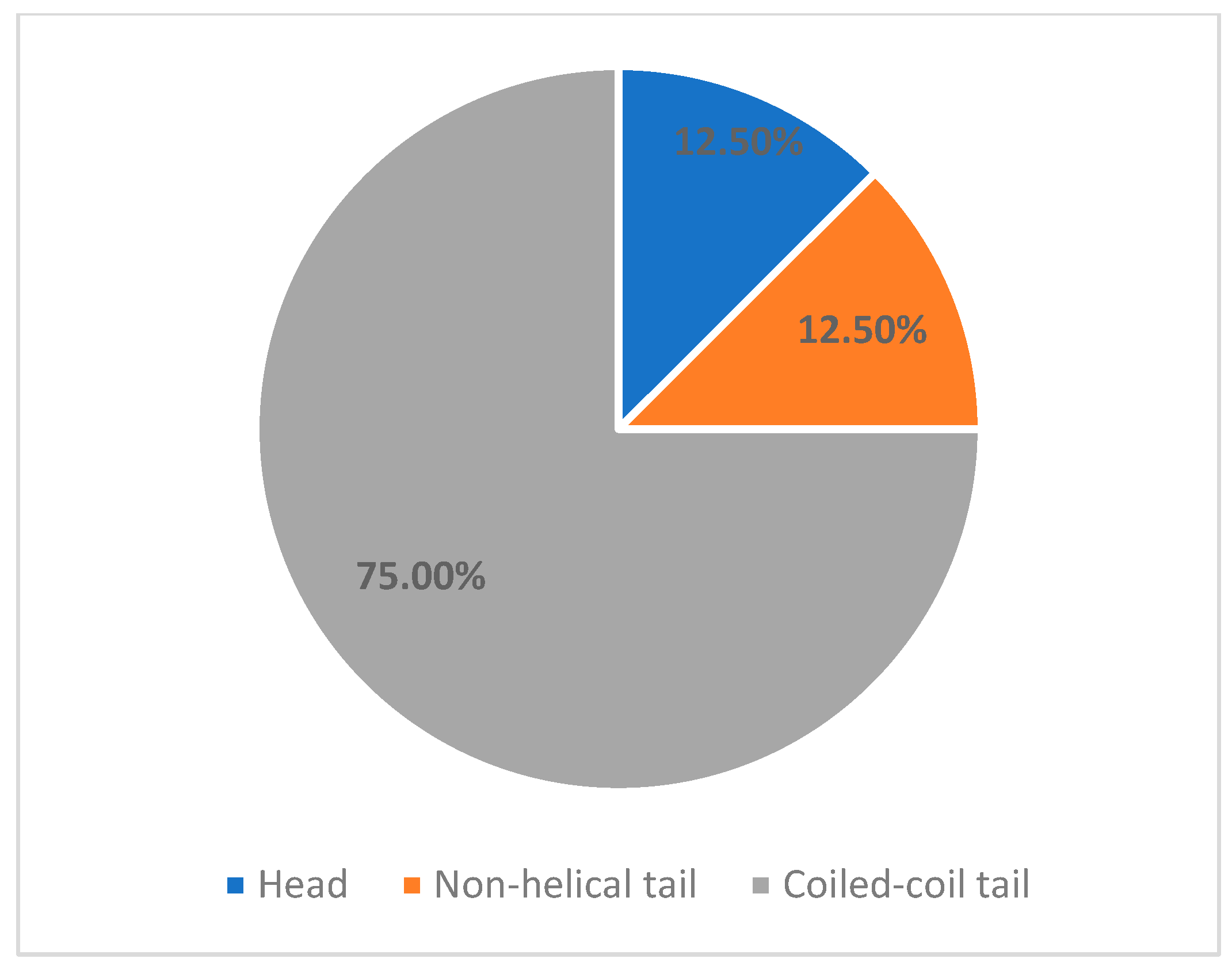

- MYH9 c.3838G>A, VUSPatient: 9-year-old female.Previous treatment: Long-term corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulinDisease evolution to date: Patient was referred to our unit for refractory thrombocytopenia after 3 months of continuous prednisone use. The following year, patient maintained severe thrombocytopenia but also encountered multiple severe infectious episodes, including opportunistic infections with Clostridium Difficile. Primary immunodeficiency was suspected, and the patient received monthly treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin. Following treatment, patient achieved and maintained normal platelet count, even after treatment stop. Currently, almost 4 years after debut, platelet count maintains normal, with no treatment, maximum WHO bleeding scale grade 1.Family history: Negative.Genetic aspects: Variant reevaluation classified it as Likely Pathogenic based on PS4_moderate, PM1, PM6, and PP2.Comments: Although this variant fulfilled ACMG criteria supporting a Likely Pathogenic classification (PS4_moderate, PM1, PM6, PP2), the absence of sustained thrombocytopenia raises the possibility that this variant may represent an incidental finding rather than a driver of disease in this patient. This case highlights an important limitation of ACMG-based variant interpretation, which integrates population, computational, and limited clinical data, but does not always account for incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity, or competing clinical diagnoses.Previous reports have described this variant in association with heterogeneous phenotypes, including primary immunodeficiency and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, but without definitive evidence establishing causality for MYH9-related thrombocytopenia.Accordingly, we acknowledge that the patient’s clinical course may reflect that the c.3838G>A variant requires further evidence—including familial segregation, functional studies, or additional phenotypically concordant cases—before definitive disease attribution can be established.This case underscores the necessity for cautious interpretation of VUS and Likely Pathogenic variants when clinical findings diverge from expected disease phenotypes.Our cohort confirms that MYH9-related disease is the most common genetically confirmed inherited thrombocytopenia in children. In our series, 26% (8/31) of patients carrying IT-associated variants had an MYH9 mutation. This incidence is comparable to published pediatric and mixed-age IT cohorts, where MYH9-RD ranges from 20 to 40% of inherited thrombocytopenia cases (23% in the Italian registry, 22–33% in East Asian pediatric cohorts, and ~30% in large multigene IT sequencing series) [3,7,8].The molecular spectrum in our patients revealed predominance of missense variants in the coiled-coil tail domain (6/8 patients, 75%), consistent with known MYH9 genotype distribution. These patients exhibited a mild hematologic phenotype, preserved hemostatic stability, and no extra-hematological manifestations during follow-up. In contrast, the single head-domain variant (c.287C>T) discovered in a 2-month-old was associated with the most severe hematological phenotype, recapitulating existing genotype–severity models associating motor domain variants with early disease onset, severe thrombocytopenia, and higher risk of early systemic disease [5,7,8,9,11].Non-hematologic manifestations were absent in this cohort, as renal, auditory, and ophthalmologic complications typically emerge in adolescence or adulthood. This reinforces the importance of anticipatory multidisciplinary surveillance, even in asymptomatic children [11,12].A key finding of our study is that 87.5% of genetically confirmed MYH9-RD patients were initially misdiagnosed and treated ITP, consistent with previously reported misdiagnosis rates of inherited platelet disorders [2,3] The consequences were substantial: unnecessary exposure to corticosteroids and IVIG in 7 of 8 patients, delayed molecular diagnosis (median 24 months; up to 11 years), Escalation to second-line therapies including thrombopoietin receptor agonists or repeated immunosuppression in some cases.These findings highlight a persistent diagnostic gap: macrothrombocytopenia alone remains insufficiently recognized as a red flag, despite being one of the strongest clinical discriminators against ITP [10,24]. Our results strongly support early NGS-based evaluation in infants, refractory or chronic cases, and patients with macrothrombocytopenia, aligning with emerging international recommendations advocating early genetic testing to prevent unnecessary exposure to immunosuppression, early monitorization plan for extra-hematological manifestation [3,25].

4.2. Treatment

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITP | Immune thrombocytopenia |

| IT | Inherited thrombocytopenia |

| MYH9-RD | MYH9-related disease |

| VUS | Variant of unknown significance |

| TPO-RA | Trombopoetin receptor agonist |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

References

- Rodeghiero, F.; Stasi, R.; Gernsheimer, T.; Michel, M.; Provan, D.; Arnold, D.M.; Bussel, J.B.; Cines, D.B.; Chong, B.H.; Cooper, N.; et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: Report from an international working group. Blood 2009, 113, 2386–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.M.; Nazy, I.; Clare, R.; Jaffer, A.M.; Aubie, B.; Li, N.; Kelton, J.G. Misdiagnosis of primary immune thrombocytopenia and frequency of bleeding: Lessons from the McMaster ITP Registry. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 2414–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazni, I.; Stapley, R.; Morgan, N.V. Inherited Thrombocytopenia: Update on Genes and Genetic Variants Which may be Associated With Bleeding. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balduini, C.L.; Melazzini, F.; Pecci, A. Inherited thrombocytopenia-recent advances in clinical and molecular aspects. Platelets 2017, 28, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecci, A.; Ma, X.; Savoia, A.; Adelstein, R.S. MYH9: Structure, functions and role of non-muscle myosin IIA in human disease. Gene 2018, 664, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foth, B.J.; Goedecke, M.C.; Soldati, D. New insights into myosin evolution and classification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3681–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, K.; Greinacher, A. MYH9-Related Platelet Disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009, 35, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Panza, E.; Pujol-Moix, N.; Klersy, C.; Di Bari, F.; Bozzi, V.; Gresele, P.; Lethagen, S.; Fabris, F.; Dufour, C.; et al. Position of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMMHC-IIA) mutations predicts the natural history of MYH9-related disease†. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Klersy, C.; Gresele, P.; Lee, K.J.; De Rocco, D.; Bozzi, V.; Russo, G.; Heller, P.G.; Loffredo, G.; Ballmaier, M.; et al. MYH9-related disease: A novel prognostic model to predict the clinical evolution of the disease based on genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum. Mutat. 2014, 35, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, P.; Biino, G.; Pecci, A.; Civaschi, E.; Savoia, A.; Seri, M.; Melazzini, F.; Loffredo, G.; Russo, G.; Bozzi, V.; et al. Platelet diameters in inherited thrombocytopenias: Analysis of 376 patients with all known disorders. Blood 2014, 124, e4–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verver, E.J.; Topsakal, V.; Kunst, H.P.; Huygen, P.L.; Heller, P.G.; Pujol-Moix, N.; Savoia, A.; Benazzo, M.; Fierro, T.; Grolman, W.; et al. Nonmuscle Myosin Heavy Chain IIA Mutation Predicts Severity and Progression of Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Patients With MYH9-Related Disease. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Lee, H.; Kang, H.G.; Moon, K.C.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Ha, I.S.; Ahn, H.S.; Choi, Y.; Cheong, H.I. Renal manifestations of patients with MYH9-related disorders. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011, 26, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rocco, D.; Pujol-Moix, N.; Pecci, A.; Faletra, F.; Bozzi, V.; Balduini, C.L.; Savoia, A. Identification of the first duplication in MYH9-related disease: A hot spot for unequal crossing-over within exon 24 of the MYH9 gene. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 52, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Biino, G.; Fierro, T.; Bozzi, V.; Mezzasoma, A.; Noris, P.; Ramenghi, U.; Loffredo, G.; Fabris, F.; Momi, S.; et al. Alteration of liver enzymes is a feature of the MYH9-related disease syndrome. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunishima, S.; Matsushita, T.; Kojima, T.; Amemiya, N.; Choi, Y.M.; Hosaka, N.; Inoue, M.; Jung, Y.; Mamiya, S.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. Identification of six novel MYH9 mutations and genotype-phenotype relationships in autosomal dominant macrothrombocytopenia with leukocyte inclusions. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 46, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenni, C.; Mansard, L.; Blanchet, C.; Baux, D.; Vaché, C.; Baudoin, C.; Moclyn, M.; Faugère, V.; Mondain, M.; Jeziorski, E.; et al. When Familial Hearing Loss Means Genetic Heterogeneity: A Model Case Report. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunishima, S.; Kojima, T.; Matsushita, T.; Tanaka, T.; Tsurusawa, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Okamura, T.; Amemiya, N.; Nakayama, T.; et al. Mutations in the NMMHC-A gene cause autosomal dominant macrothrombocytopenia with leukocyte inclusions (May-Hegglin anomaly/Sebastian syndrome). Blood 2001, 97, 1147–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S.; Fazal, S.; Akinfolarin, A.A. Unwrapping the Enigma: A Rare Case of MYH9 Nephropathy: TH-PO496. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35, 1081–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondel, C.; Vodovar, N.; Knebelmann, B.; Grünfeld, J.P.; Gubler, M.C.; Antignac, C.; Heidet, L. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Cao, L.J.; Su, J.; Yu, Z.Q.; Bai, X.; Ruan, C.G. Clinical, pathological, and genetic analysis of ten patients with MYH9-related disease. Acta Haematol. 2013, 129, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbolini, D.J.; Morel-Kopp, M.; Chen, Q.; Gabrielli, S.; Dunlop, L.C.; Chew, L.P.; Blair, N.; Brighton, T.A.; Singh, N.; Ng, A.P.; et al. Thrombocytopenia and CD34 expression is decoupled from α-granule deficiency with mutation of the first growth factor-independent 1B zinc finger. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ghosh, K.; Daly, M.E.; Hampshire, D.J.; Makris, M.; Ghosh, M.; Mukherjee, L.; Bhattacharya, M.; Shetty, S. Congenital macrothrombocytopenia is a heterogeneous disorder in India. Haemophilia 2016, 22, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, K.B. A Case of Thrombocytopenia with MYH9 Gene Mutation Found in Siblings. Soonchunhyang Med. Sci. 2024, 30, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Ahmed, Z. Drug-associated renal dysfunction and injury. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2006, 2, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduini, C.L.; Pecci, A.; Noris, P. Diagnosis and management of inherited thrombocytopenias. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2013, 39, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz-Bujna, J.; Miśkiewicz-Migoń, I.; Kozłowska, M.; Bąbol-Pokora, K.; Irga-Jaworska, N.; Młynarski, W.; Kałwak, K.; Ussowicz, M. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in MYH9-related congenital thrombocytopenia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2024, 71, e31005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Rong, L.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y. Umbilical cord blood transplantation for MYH9-related disorders. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Chen, T.; Xiao, M. MYH9-related inherited thrombocytopenia: The genetic spectrum, underlying mechanisms, clinical phenotypes, diagnosis, and management approaches. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 8, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, R.E. Drugs that affect platelet function. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2012, 38, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varon, D.; Spectre, G. Antiplatelet agents. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2009, 2009, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, S.; Noris, P.; Bury, L.; Heller, P.G.; Santoro, C.; Kadir, R.A.; Butta, N.C.; Falcinelli, E.; Cid, A.R.; Fabris, F.; et al. Bleeding risk of surgery and its prevention in patients with inherited platelet disorders. Haematologica. 2017, 102, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Birchall, J.; Allard, S.; Bassey, S.J.; Hersey, P.; Kerr, J.P.; Mumford, A.D.; Stanworth, S.J.; Tinegate, H. Guidelines for the use of platelet transfusions. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 176, 365–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, C.S. Platelet transfusion refractoriness: How do I diagnose and manage? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2020, 2020, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehbai, A.S.; Abraham, J.; Brown, V.K. Perioperative management of a patient with May-Hegglin anomaly requiring craniotomy. Am. J. Hematol. 2005, 79, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Gresele, P.; Klersy, C.; Savoia, A.; Noris, P.; Fierro, T.; Bozzi, V.; Mezzasoma, A.M.; Melazzini, F.; Balduini, C.L. Eltrombopag for the treatment of the inherited thrombocytopenia deriving from MYH9 mutations. Blood 2010, 116, 5832–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninetti, C.; Gresele, P.; Bertomoro, A.; Klersy, C.; De Candia, E.; Veneri, D.; Barozzi, S.; Fierro, T.; Alberelli, M.A.; Musella, V.; et al. Eltrombopag for the treatment of inherited thrombocytopenias: A phase II clinical trial. Haematologica 2020, 105, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassandro, G.; Carriero, F.; Noviello, D.; Palladino, V.; Del Vecchio, G.C.; Faienza, M.F.; Giordano, P. Successful Eltrombopag Therapy in a Child with MYH9-Related Inherited Thrombocytopenia. Children 2022, 9, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddu, D.; Amin, S.; Ying, Y.M. Characterization of sensorineural hearing loss in patients with MYH9-related disease: A systematic review. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 43, e298–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients No. | 8 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| F | 4 (50%) |

| M | 4 (50%) |

| Age at first presentation | 1.5 year |

| Median (range) | (0–14) |

| Platelet count—first presentation | 35.5 × 109/L |

| Median (range) | (7–126) |

| No. patients treated as ITP | 7 (87.5%) |

| Disease time evolution until genetic confirmation | 24 months |

| Median (range) | (2–132) |

| No. patients with prior family history | 3 (37.5%) |

| Variant | Location | Exon | Type | Classification | Reclasification | Age at Onset | Family History | Thrombocyte Levels (×109/L) | Macro Thrombocytopenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.3494C>T | Coiled-coil Tail | 27 | Missense | Pathogenic | N/A | 7 | Yes | 50–60 | Yes |

| c.4270G>A | Coiled-coil Tail | 31 | Missense | Pathogenic | N/A | At birth | No | 40–85 | Yes |

| c.4270G>A | Coiled-coil Tail | 31 | Missense | Pathogenic | N/A | At birth | Yes | 40–50 | Yes |

| c.287C>T | Head | 2 | Missense | Pathogenic | N/A | At birth. | No | <10 | Yes |

| c.5797C>T | Non-helical Tail | 41 | Nonsense | Pathogenic | N/A | 8 m.o. | Yes | 60–70 | Yes |

| c.3838G>A | Coiled-coil Tail | 27 | Missense | VUS/Benign | Likely Pathogenic | 7 | No | Normal | No |

| c3485+6C>T | Coiled-coil Tail | 26 | Splice-region | VUS | VUS | 10 m.o. | No | <10 | No |

| c.5411A>G | Coiled-coil Tail | 38 | Missense | VUS | Likely Pathogenic | 10 y.o. | No | 70–80 | No |

| Variant (NM_002473.5) | Initial Classification | Final Classification | ACMG Evidence Codes Applied | Evidence Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.3838G>A | VUS | Likely Pathogenic | PS4_Moderate, PM1, PM6, PP2 | Reported in affected individuals; MYH9 hotspot; absent in population databases; phenotype consistent with MYH9-RD. |

| c.3485+6C>T | VUS | VUS (unchanged) | PM2_Supporting, BP4 | Near splice donor; absent from controls; in silico effect uncertain; insufficient functional evidence. |

| c.5411A>G | VUS | Likely Pathogenic | PM1, PM2, PM6, PP2 | Located in conserved functional domain; absent from controls; MYH9 intolerant to benign missense variation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obrisca, R.; Serbanica, A.; Marcu, A.; Bica, A.; Jercan, C.; Avramescu, I.; Radu, L.; Jardan, C.; Colita, A. Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of MYH9-Thrombocytopenia: Insights from a Single Centric Pediatric Cohort. Children 2025, 12, 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111563

Obrisca R, Serbanica A, Marcu A, Bica A, Jercan C, Avramescu I, Radu L, Jardan C, Colita A. Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of MYH9-Thrombocytopenia: Insights from a Single Centric Pediatric Cohort. Children. 2025; 12(11):1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111563

Chicago/Turabian StyleObrisca, Radu, Andreea Serbanica, Andra Marcu, Ana Bica, Cristina Jercan, Irina Avramescu, Letita Radu, Cerasela Jardan, and Anca Colita. 2025. "Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of MYH9-Thrombocytopenia: Insights from a Single Centric Pediatric Cohort" Children 12, no. 11: 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111563

APA StyleObrisca, R., Serbanica, A., Marcu, A., Bica, A., Jercan, C., Avramescu, I., Radu, L., Jardan, C., & Colita, A. (2025). Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of MYH9-Thrombocytopenia: Insights from a Single Centric Pediatric Cohort. Children, 12(11), 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111563